So I thought it might be useful to lay out, in a handful of pictures, how Spain got into its current state. (All of the data come from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database). There’s a kind of classic simplicity about the story — it’s almost like a textbook example. Unfortunately, millions of people are suffering the consequences.

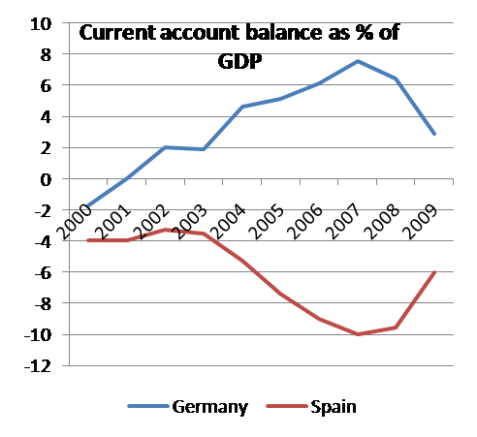

The story begins with the Spanish real estate bubble. In Spain, as in many countries including our own, real estate prices soared after 2000. This brought massive inflows of capital; within Europe, Germany moved into huge current account surplus while Spain and other peripheral countries moved into huge deficit:

IMF

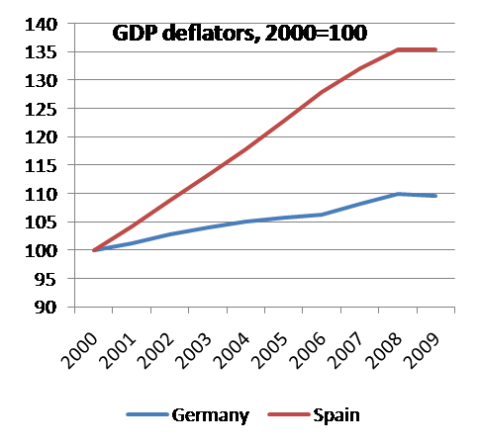

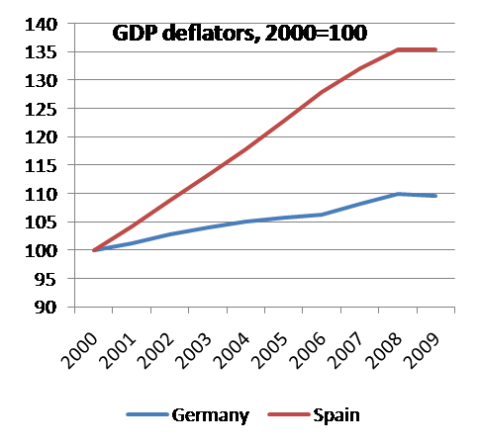

IMFThese big capital inflows produced a classic transfer problem: they raised demand for Spanish goods and services, leading to substantially higher inflation in Spain than in Germany and other surplus countries. Here’s a comparison of GDP deflators (remember, both countries are on the euro, so the divergence reflects a rise in Spain’s relative prices):

IMF

IMFBut then the bubble burst, leaving Spain with much reduced domestic demand — and highly uncompetitive within the euro area thanks to the rise in its prices and labor costs. If Spain had had its own currency, that currency might have appreciated during the real estate boom, then depreciated when the boom was over. Since it didn’t and doesn’t, however, Spain now seems doomed to suffer years of grinding deflation and high unemployment.

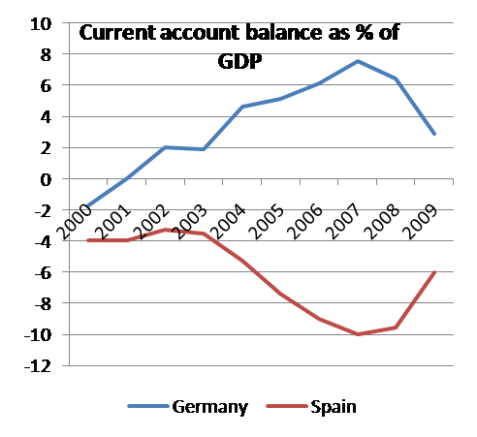

Where are budget deficits in all this? Spain’s budget situation looked very good during the boom years. It is running huge deficits now, but that’s a consequence, not a cause, of the crisis: revenue has plunged, and the government has spent some money trying to alleviate unemployment. Here’s the picture:

IMF

IMFSo, whose fault is all this? Nobody’s, in one sense. In another sense, Europe’s policy elite bears the responsibility: it pushed hard for the single currency, brushing off warnings that exactly this sort of thing might happen (although, as I said, even euroskeptics never imagined it would be this bad).

Am I calling, then, for breakup of the euro. No: the costs of undoing the thing would be immense and hugely disruptive. I think Europe is now stuck with this creation, and needs to move as quickly as possible toward the kind of fiscal and labor market integration that would make it more workable.

![[hourly_wage_cuts_chart.png] [hourly_wage_cuts_chart.png]](http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_Et4TQ-a0gGU/S5PwzgY6MuI/AAAAAAAAC6k/tGAwpoz7qNk/s1600/hourly_wage_cuts_chart.png)