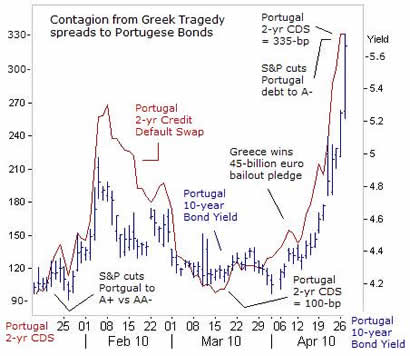

Here is a nice summary of the contagion factors in Europe.

Contagion: Looking Ahead to Spain and Italy

crisis will soon spread to other countries. Ireland and Portugal have

long been seen as susceptible to going the same way as Greece, but

recently Italy has joined the group of countries seen to be potentially

vulnerable.

So like many, I’ve been thinking a lot about

contagion this week. But even though it seems to be common knowledge in

the business press that if and when Greece defaults the crisis will

immediately deepen for other countries, cogent explanations for why that

might happen have been scarce. So I think it’s helpful to try to get

more specific about why we think the crisis might or might not spread

further to Spain or Italy. That will help us better understand whether

those fears are real or overblown.

Most of the economic

literature about contagion has focused on its applicability to currency

crises, such as the EMU crisis of 1992-3 or the “Asian Flu” of 1998.

However, the logic is similar when applied to sovereign debt crises. As

a reminder, here’s a list of some of the explanations that have been

put forward to explain previous episodes where financial crises spread

from country X to nearby and similar country Y:

- a common external shock: whatever factor originally tipped country X into crisis has the same effect on country Y, so it will also push Y into crisis.

- the “wake up call”: when

country X enters a crisis investors suddenly reevaluate their

portfolios for risk, and sell off assets related to any country similar

to X, thereby precipitating a crisis for country Y. - liquidity concerns among common creditors: crisis

in country X causes creditors (e.g. banks) to suffer losses that force

them to sell off assets in country Y, precipitating a crisis in Y. - cross-market hedging among common creditors: crisis

in country X means that the portfolio of creditors (e.g. banks) has

suddenly become more risky on average, so they respond by reducing their

risk exposure elsewhere in their portfolio, in part by selling off the

assets of any similar country also seen as risky, such as Y. - political contagion: the

actions taken to deal with the crisis in country X (e.g. dropping a

fixed exchange rate, or in this case, default) make it less costly for

country Y to do the same thing, and investors realize this, sell off the

assets of country Y, and thus precipitate a crisis for country Y as

well.

The thing that these mechanisms have in common is that

they all create a process of self-fulfilling expectations, where a loss

of investor demand or confidence causes a sell-off of assets, which

causes a crisis, which validates the original loss of confidence.

But

in the case of Greece, I don’t think that most of these sources of

contagion are of real concern, simply because the crisis has been drawn

out over such a long period of time now that investors and creditors

have all had plenty of time to expect and plan for a Greek default. So I

think that the only one of these possible sources of contagion that

might apply in this case is the last one, which for convenience I’ve

labeled “political contagion”.

If Greece is seen to default (and

it seems likely that however the EU chooses to package and label the

terms of the new Greek bailout, it will involve some sort of "soft

default"), then investors will have been provided a demonstration of how

a limited default could work for other euro countries. This poses an

enormous problem for European policymakers. Whatever new bailout and

debt restructuring they agree to for Greece — especially if it

substantially reduces the Greek debt burden going forward — could

prompt Ireland and Portugal to ask for the same terms. On the other

hand, if the terms of the Greek deal do not sufficiently reduce Greece’s

debt burden then the deal will have done nothing to resolve the

fundamental issue of insolvency, and policymakers will be right back

where they started at some point down the road.

But developments

in the financial markets over the past week have reminded everyone that

policymakers may need to worry less about Ireland and Portugal, and

instead be more far-sighted and consider first and foremost the impact

on Spain and Italy. Because when it comes to those two countries, it is

clear to everyone that if the debt crisis takes serious hold on them

then a financial crisis will become a financial catastrophe.

Paradoxically,

one way to help cut off the speculation in the financial markets that

Spain and Italy could at some point be candidates for bailouts and/or

debt restructuring would be for the EU and ECB to be relatively generous

with Greece. If the transfers to Greece from the core euro countries

are large – so large that they are difficult for France and Germany to

agree to – then investors will have to draw the conclusion that such a

deal could never, ever be applicable to Spain and Italy. Spain and

Italy are just too big, and the aid packages that worked for Greece

would never be feasible for them. While that wouldn’t necessarily stop

speculation that Spain and/or Italy might someday be unable to service

their debts, it would definitely stop speculation that they would ever

be candidates for a Greek-style managed default. And that might be

enough to help.