A wonderful discussion of recent financial flows is provided by Brad Setser. The reserve flow dynamics can be worked out nicely with the aid of a Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rate Mundell Flemming model (Chapter 18 and 19). However, the Setser's piece does have some jargon, so if you have a life and dont want to slug though the IMF report (he criticizes) and his own theory, here are the key paragraphs:

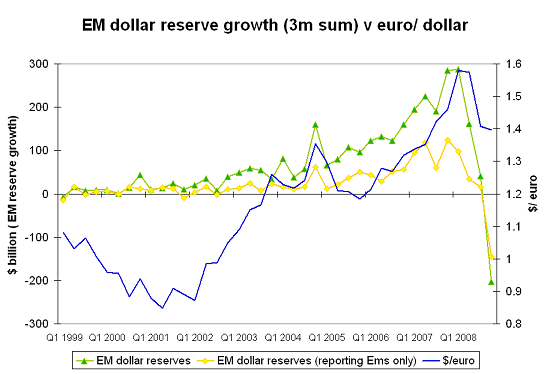

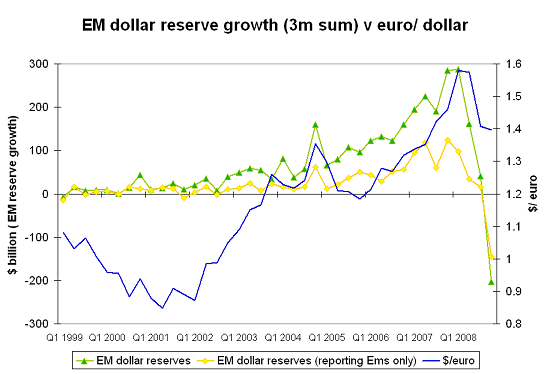

When the US slowed and the global economy (and the European economy) didn’t, private money moved from the slow growing US to the fast growing emerging world in a big way. The IMF’s data suggests that capital flows to the emerging world more than doubled in 2007 – and 2006 wasn’t a shabby year. Net private inflows to emerging economies went from around $200 billion in 2006 to $600 billion in 2007. Private investors wanted to finance deficits in the emerging world, not the US – especially when US rates were below rates globally. Normally, that would force the US to adjust – i.e. reduce its (large) current account deficit. That didn’t really happen. Why? Simple: The money flooding the emerging world was recycled back into the US by emerging market central banks. European countries generally let their currencies float against the dollar. But many emerging economies didn’t let their currencies float freely. A rise in demand for their currency leads to a rise in reserves, not a rise in [the price of the currency]. As a result, there has been a strong correlation between a rise in the euro (i.e. a fall in the dollar) and a rise in the reserves of the world’s emerging economies. Consider this chart – which plots [the 3 months sum of] emerging market [EM] dollar reserve growth from the IMF [official foreign currency reserve] data against the euro.

If the rise in reserve growth in the emerging world is a sign of the amount of pressure on the dollar, then the dollar was under tremendous pressure from late 2006 on. It central banks had broke – and lost their willingness to add to their dollar holdings then – there likely would have been a dollar crisis. A fall in inflows would have forced the US to adjust well before September 2008… Last week felt a more like the fourth quarter of 2007 than the fourth quarter of 2008. For whatever reason — an end to deleveraging and a rise in the world’s appetite for emerging market risk or concern that the Fed’s desire to avoid deflation would, in the context of a large fiscal deficit, would lead to a rise in inflation and future dollar weakness – demand for US assets fell. In some sense, the dollar’s fall shouldn’t be a surprise. Low interest rates typically help to stimulate an economy is by bringing the value of the currency down and thus helping exports.