… that depends on what your objectives are…

Here is the issue: recent jobs and inventory data seems to indicate that the economy is starting to move off the bottom. However, one Oracle, whose business acumen I happen to trust blindly, tells me that the business community is paralyzed — the men and women who create much of the wealth in the US economy lament that an opportunity was squandered to pass tax cuts that could have rivaled the dramatic Kennedy (D) and Reagan (R) cuts.

First: The Facts:

The Kennedy tax cut (actually passed posthumously as The Revenue Act of 1964) was designed to boost the economy long after the April/1960-February/1961 recession. It was an income tax cut designed to reduce the top tax rate from 91 percent to 70 percent and the top corporate rate from 52 percent to 48 percent.

The Reagan tax cut, formally known as The Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, was enacted in August 1981, at the start of the deep July/1981-November/1982 recession. Its hallmark was a income tax reduction from 70% to 50% for top earners and a reduction from 14% to 11% for low income households. (The 1986 Reagan tax cut subsequently reduced the top tax rate from 50% to 28% while it raised the bottom rate from 11%to 15%. It also increased the (minimum) corporate tax rate).

The 2009 Stimulus, formally known as American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, was enacted in February 2009, just after financial markets experienced sudden cardiac arrest (or sudden financial arrest, as Ricardo Caballero calls it). The US economy was not only in its worst recession since the Great Depression, but it was also in a liquidity trap, where interest rates are zero and demand is still so anemic that commercial banks deposit funds at Federal Reserve in lieu of lending on projects. The 2009 Stimulus was a one time expenditure package of $878 billion. 37% of the package went to tax cuts ($288 billion), $144 billion (18%) to state/local fiscal relief (mostly Medicaid and education), and $357 billion (45%) to federal social programs and federal spending programs.

Source

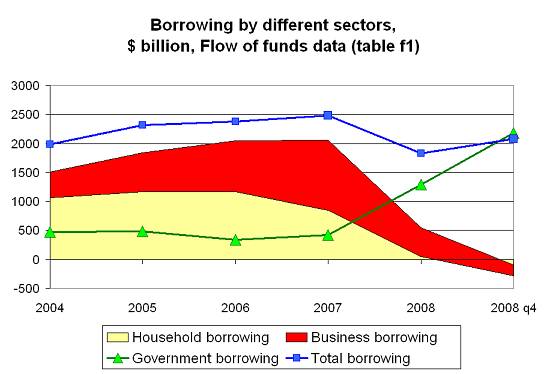

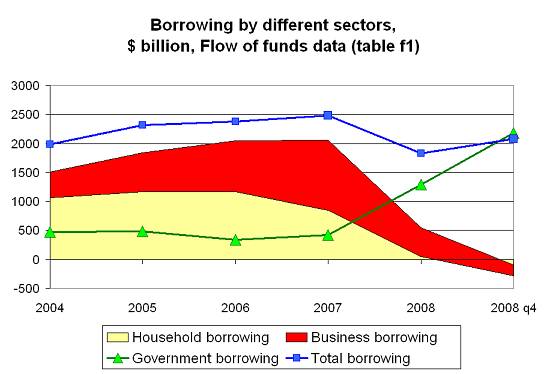

Second: The Data

While the Kennedy and Reagan tax cuts were surgically targeted to permanently reduce income taxes, the 2009 Stimulus was designed to deliver a one-time defibrillation to resuscitate the economy. To get an idea of the magnitudes of the various measures, it is helpful to compare apples with apples. Below is a graph that compares the prominent tax cuts and the one-time 2009 stimulus. The graph also adds the recent Bush Tax Cuts (Economic Growth and Tax Reform Reconciliation Act of 2001, Job Creation and Worker Assistance Act of 2002, Jobs and Growth Tax Relief and Reconciliation Act of2003).

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation; TaxFoundation, http://www.recovery.gov/

The magnitude and the focus of these four measures is clearly very different. Also we are comparing the annual effects only – these effects accumulate over time for permanent measures. Reagan and Kennedy tax cuts were smaller per annum, surgically focused on income tax cuts, and permanent. The 2009 Stimulus instead was a one-time hodgepodge of targeted subsidies/pork barrel; The fact that it was not a permanent measure reflects the thoughts of one of the key designers: being timely, targeted, and temporary.

Third: The Theory

Why not provide a corporate tax break or an income tax break as part of the package? Key arguments are related to the type of crisis the US was facing in late 2008, early 2009. The central task of the stimulus was to act quickly and not permanently by stimulating demand. Several members of congress lobbied for permanent tax cuts, but that policy would have missed the mark. While permanent tax cuts may be beneficial for the economy in the long run, they would not serve the purpose of assisting the economy's exit from the liquidity trap. Hence in evaluating policy options, it is important to keep in mind the objective of the 2009 Stimulus.

For a fiscal stimulus to increase growth quickly, the vast majority of economists agree that the policy measure must focus on spending increases and temporary tax rebates for low- and moderate-income families, who are likely to spend the money rather than save it. The alternative of lowering corporate or capital gains tax is often seen as a distant second.

While corporate tax cuts lower the cost of capital and provide incentives to invest, there exists a long literature, starting with noted economist Dale Jorgenson’s work in the 1960s, which consistently documents that the cost of capital plays a much smaller role in determining investment than sales growth. Without prospects for increased sales growth, businesses have no reason to undertake risky investments, no matter how cheap it is. This point is driven home rather decisively by the ineffectiveness of the Fed's latest interest rate cuts in raising investment.

The other argument that economist put forth is that today's corporate tax cuts would largely reward past investments rather than new investments. There may exist good reasons to lower the corporate tax rate (i.e., to remain competitive relative to corporate taxes in other countries, or to eliminate the double taxation because capital pays the tax to the corporation and the profits are again taxed at the corporate level), but it would be an unlikely candidate to jump start the economy out of the liquidity trap. Proponents of lower capital gains tax cuts suggest that it would induce people to invest in riskier assets, such as corporate shares. This lowers the cost of capital and making it easier for companies to obtain financing. The same argument as above, which negated the effectiveness of corporate tax cuts, applies then for capital gains taxation.

There is not much disagreement on the theory among economists. Even Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Economy.com, and advisor to John McCain’s during the presidential race, rated a corporate tax rate cut as one of the least effective of all tax and spending options to provide the needed jolting stimulus to the economy. He estimates that corporate tax cuts would generate in the short run only 30 cents in economic demand for every dollar spent on the tax cut. So it is certainly true that the tax cuts in the 2009 stimulus do not “pass the supply-side test” as Stephen Entin suggested, but we must keep in mind that the stimulus package was not designed as a supply-side measure.

This reduces the question to how solid the evidence is that stimulus, not tax cuts are the surest and quickest way to cause the economy to rebound? In terms of aggregate demand and the data that we possess, the effect of spending vis a vis tax cuts can be calculated by the OECD's macroeconomic model. The graphic clarifies why a temporary stimulus should be front loaded with expenditures, but also include tax cuts to maximize the total stimulus effect over time.

Multipliers at horizons of N = {1,2,3,4,5} years after implementation, expressed as the ratio of change in GDP relative to baseline to one percentage point of GDP change in X, where X= {government, consumption spending, wage/salary taxes}. Source:Dalsgard, Andre andRichardson (2001).

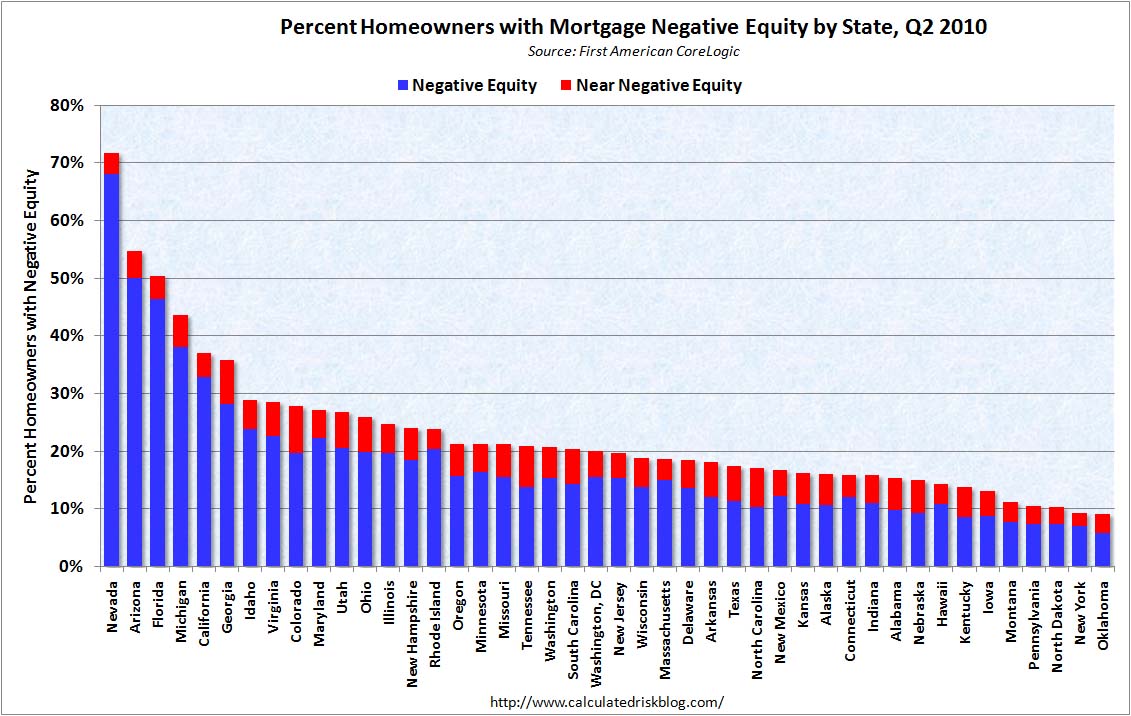

Update and Addendum: Conceptually one cannot get away from the fact that comparing a temporary stimulus to permanent policy changes such as tax cuts is is a bit like comparing apples and oranges. So intellectually the interesting question at this stage would be: what permanent changes should President Obama and policy makers undertake today, to foster an economic expansion in the future.

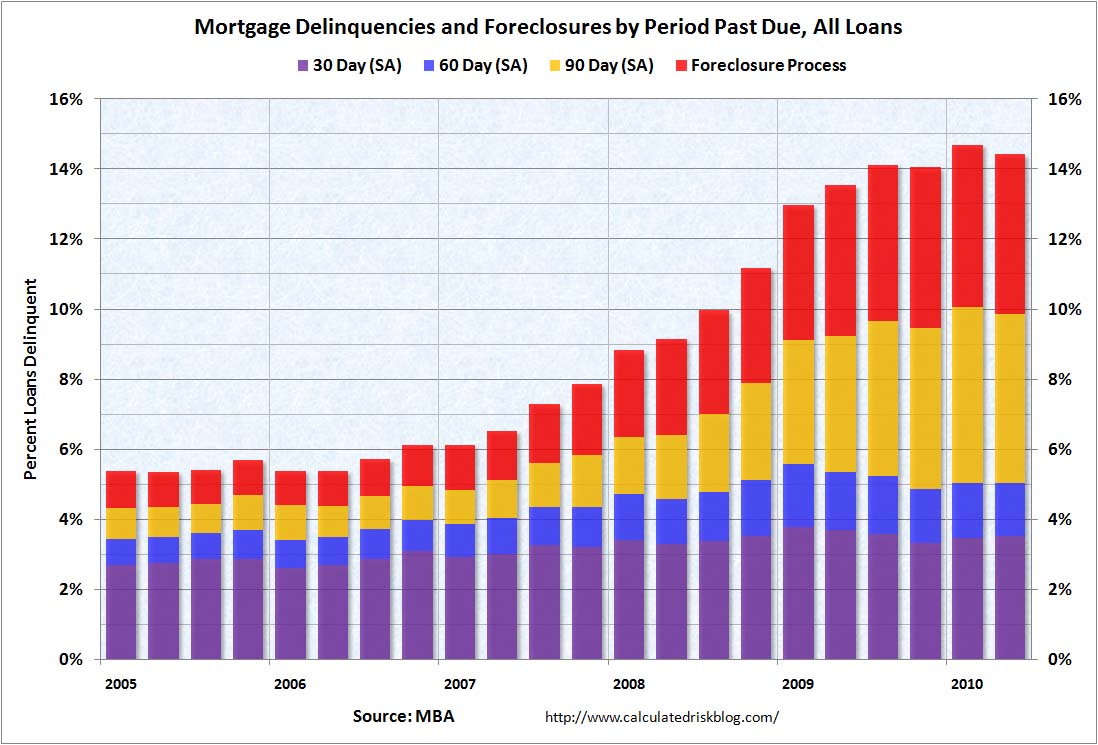

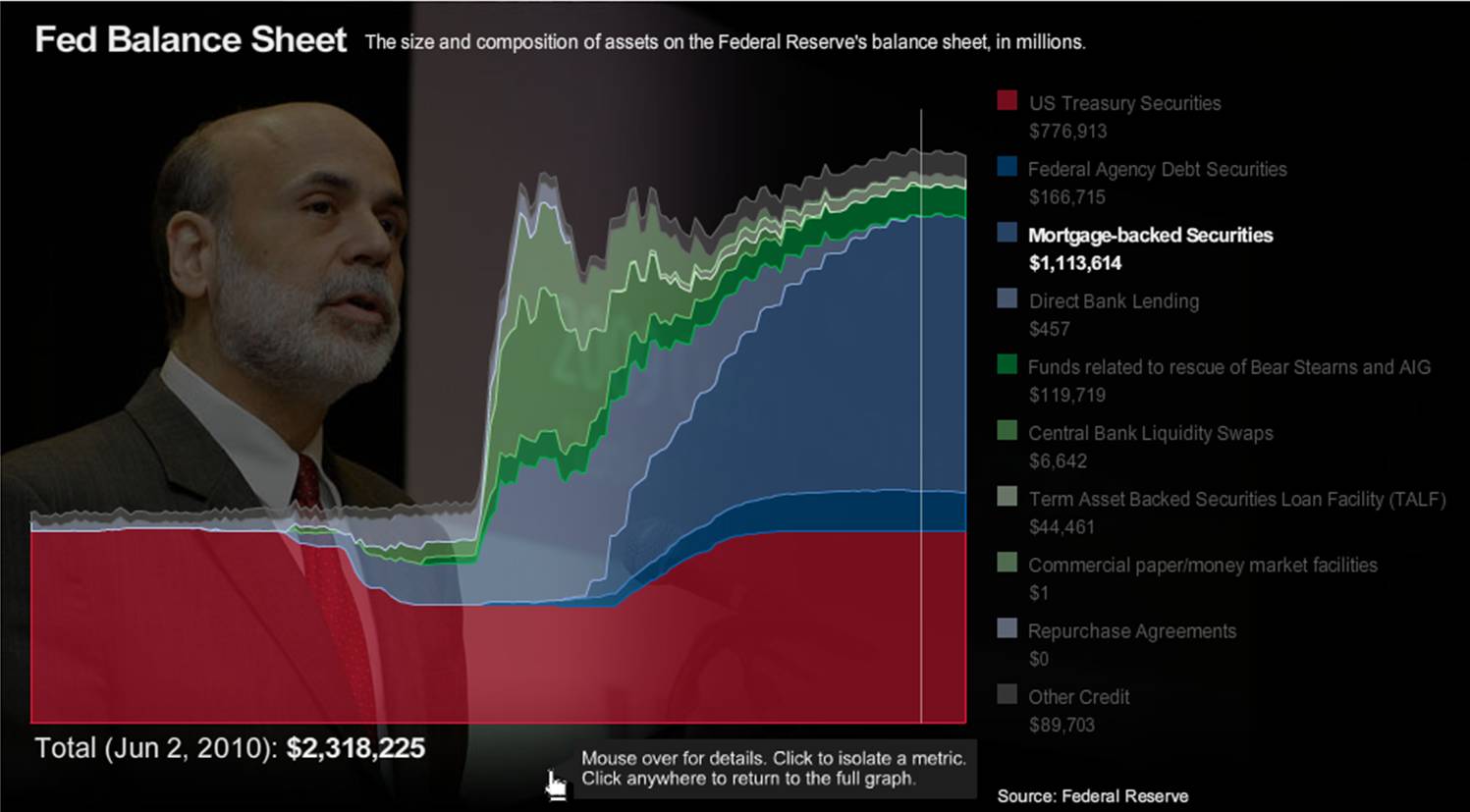

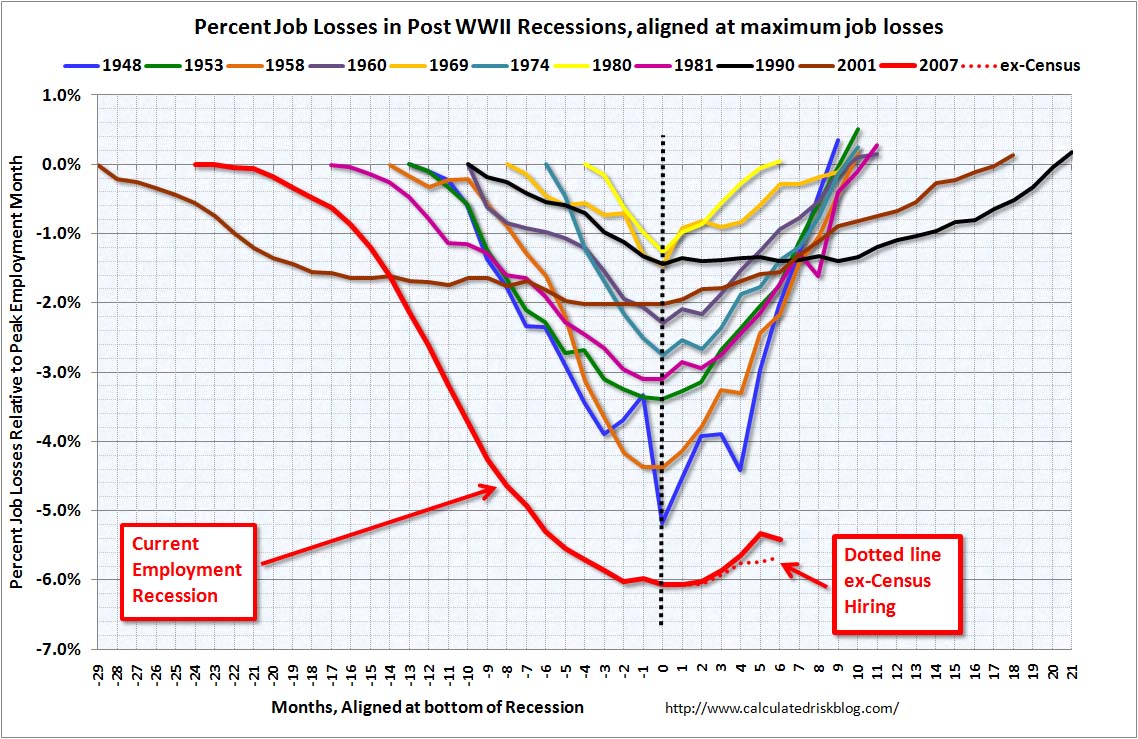

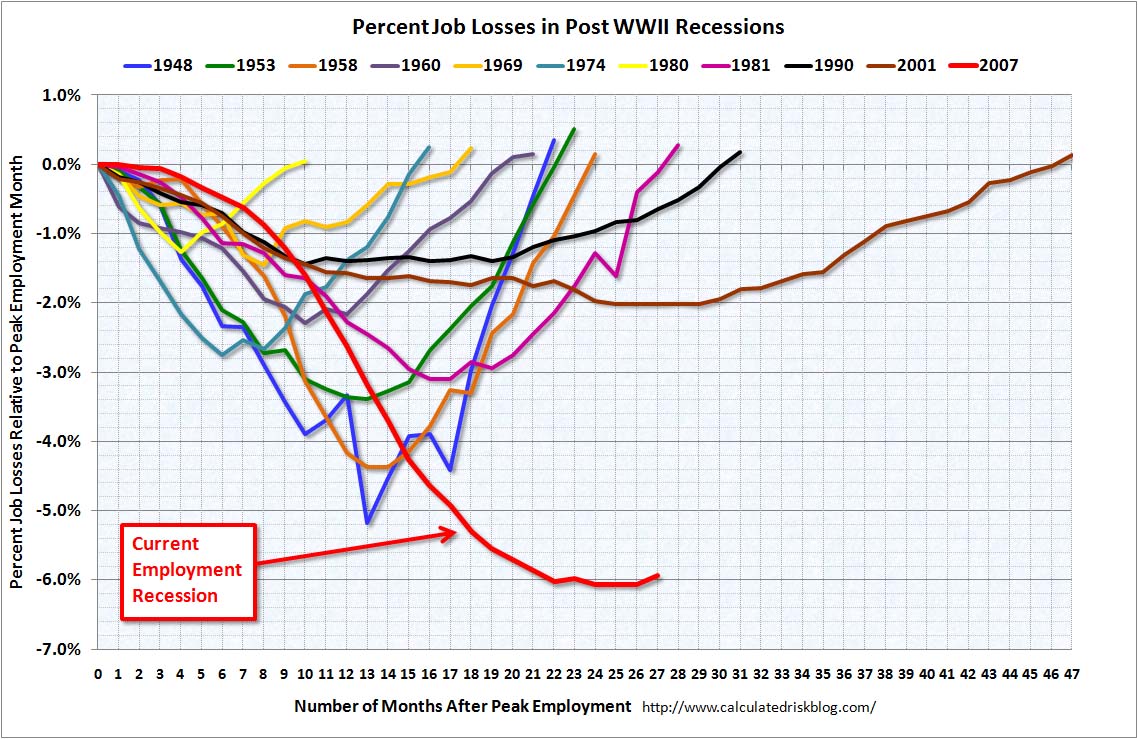

Some economists may think its a bit early to ask that question, since we are still in the liquidity trap (interest rates are still constrained from below at zero and excess reserves are still staggering). This, of course raises the question, whether the past stimulus has not worked (the difibrillation did not work, the patient is still in cardiac arrest), and why.

You guessed it, economists have two options on this: freshwater water economists never saw a liquidity trap and chalked the crisis off to a shift in the population's desire to be voluntarily unemployment (Casey Mulligan's "Great Vacation" hypothesis – this is not a joke). Fresh water economists who think we are still in a liquidity trap do not think the current, second stimulus is nearly large enough (if the first defibrillators 1000 volt shock did not revive the heart, you recharge it and use another 1000 volt jolt, you don't take a 9 volt battery the second time around).

![[IMF]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/WO-AA574_IMF_NS_20100420215204.gif)

.jpg)