Time Magazine and the Economist Magazine report that Argentinians smell a rat. When interest rates at at 20%, if no “Austerity,” then what?  Things have taken a rather dramatic turn for the worst over the past two weeks. After the central bank hiked rates three times in the space of a week for a total of 1,275 basis points in an effort to arrest the slide in the peso. But that wasn’t enough as the Argentinean Peso (ARS) careened to a new all-time low ahead of another CB rate decision.

Things have taken a rather dramatic turn for the worst over the past two weeks. After the central bank hiked rates three times in the space of a week for a total of 1,275 basis points in an effort to arrest the slide in the peso. But that wasn’t enough as the Argentinean Peso (ARS) careened to a new all-time low ahead of another CB rate decision. Bloomberg noted, the bid/offer was “very wide with almost no real trades executed.” This crisis goes back to a poorly communicated December CB decision to up the inflation target along with a couple of rate cuts in January. Now the chickens have come home to roost and it’s a bloodbath, both for the currency and for the bonds, which are plunging:

Bloomberg noted, the bid/offer was “very wide with almost no real trades executed.” This crisis goes back to a poorly communicated December CB decision to up the inflation target along with a couple of rate cuts in January. Now the chickens have come home to roost and it’s a bloodbath, both for the currency and for the bonds, which are plunging: Needless to say, it doesn’t help that U.S. interest rates are rising. Standard results from a Mundell Fleming Monetary Policy expansion…

Needless to say, it doesn’t help that U.S. interest rates are rising. Standard results from a Mundell Fleming Monetary Policy expansion…

Category Archives: Mundell Fleming

Capital Flows

As the IMF finally comes around to realize that unfettered capital flows may not be optimal policy for all countries at all times, not all countries agree that the new IMF stance is appropriate.

At the same time, China is moving in to the opposite direction – well somewhat. The Chinese capital account has been one of the most tightly regulated, which is about to change – slightly, as the WSJ reports. This is a good exercise to see how policy effectiveness in China are going to change in the Mundell Fleming model with fixed exchange rates!

Straight From the Oracle: Italy Is The Threat

Ok, Portugal is a done deal, now people start hand wringing whether Spain is next. Bob Mundell, "Father of the Euro" or better known as the creater of the "Mundell Fleming Model" has been warning for a while that Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain are trivial compared to a potential crisis in Italy. Let's start watching the risk premium on Italian goverment debt. It sounded far out in 2010, today it is an uncomfortable reality.

The China Syndrom

China is learning about the basic principles of open economy macro: Sterilize the balance of payments surplus or experience increases in output that eventually lead to inflation. Use the TB/Y diagram or the Fixed Exchange Rate MF model to show how the undervaluation of a currency leads to massive reserve accumulations that must, eventually, be sterilized. It will be an interesting case study to count the ways in which China will try to maintain control of its money supply, and how follow effective each measure is going to be.

International Finance Trilemma

According to the Mundell-Fleming model, a small, open economy cannot achieve all three of these policy goals at the same time:

1. A fixed exchange rate

2. An open capital market (no capital controls)

3. An independent monetary policy

in pursuing any two of these goals, a nation must forgo the third. Every course on international finance should conclude with an exercise to prove the International Finance Trilemma. GregMankiw provides the popular review of the "impossible trinity." BradDeLong provides the following concrete examples

Countries on the gold standard (like the U.S. from 1873-1914) chose to have a fixed exchange rate and open capital markets. They did not have independent monetary policy. (The U.S. did not even have a central bank, although the Treasury performed some of a central bank's functions.)

The U.S. today chooses to have an open capital market and an independent monetary policy. Thus it does not have a fixed exchange rate: you cannot take your dollars to the San Francisco Fed and exchange them for gold or foreign currency at a set price.

Countries in the Euro area, like countries on the Gold Standard, have chosen to have open capital markets and fixed exchange rates and thus they do not have independent monetary policies. The European Central Bank (the ECB) sets monetary policy for all countries in the Euro-zone.

China has (roughly) chosen to have a fixed exchange rate and an independent monetary policy. This means that they must have capital controls, which they indeed do. For example, Article 9 of The People's Bank of China Decree [2006], No. 3 states 1: An individual's foreign exchange sales and domestic individual's foreign exchange purchases shall be imposed an annual limit. Within the annual limit, an individual can conduct a sale or purchase business with a bank by presenting valid identity documents; beyond the annual limit, an individual can conduct a current account business with a commercial bank by presenting valid.

The Burda and Wyplosz textbook also provides a nice illustration. What happens if a nation tries to pursue all three goals at once? To start with they posit a nation with a fixed exchange rate at equilibrium with respect to capital flows as its monetary policy is aligned with the international market. However the nation then adopts an expansionary monetary policy to try to stimulate its domestic economy. This involves an increase of the monetary supply, and a fall of the domestically available interest rate. Because the internationally available interest rate adjusted for forex differences has not changed, market participants are able to make a profit by borrowing in the countries currency and then lending abroad – a form of Carry trade. With no capital control market players will do this en masse. The trade will involve selling the borrowed currency on the forex market in order to acquire foreign currency to lend abroad – this tends to cause the price of the nation's currency to drop due to the sudden extra supply. Because the nation has a fixed exchange rate, it must defend its currency and will sell its reserves to buy its currency back. But unless the monetary policy is changed back, the international markets will invariably continue until the governments foreign exchange reserves are exhausted, causing the currency to devalue, thus breaking one of the three goals and also enriching market players at the expense of the government that tried to break the impossible trinity.

Global Transmission of European Austerity

Here is a nice application of the large-open-economy Mundell Fleming model. The model is a work horse; there are many more sophisticated theories out there but some basic tenants remain helpful for policy analysis. This example is from Paul Krugman (those who read Chapter 19 can draw the diagram…)

Some thoughts on the fiscal austerity mania now sweeping Europe: is anyone thinking seriously about how this affects the rest of the world, the US included?

We do have a framework for thinking about this issue: the Mundell-Fleming model. And according to that model (does anyone still learn this stuff?), fiscal contraction in one country under floating exchange rates is in fact contractionary for the world as a hole. The reason is that fiscal contraction leads to lower interest rates, which leads to currency depreciation, which improves the trade balance of the contracting country — partly offsetting the fiscal contraction, but also imposing a contraction on the rest of the world. (Rudi Dornbusch’s 1976 Brookings Paper went through all this.)

Now, the situation is complicated by the fact that monetary policy is up against the zero lower bound. Nonetheless, something much like this transmission mechanism seems to be happening right now, with the weakness of the euro turning eurozone fiscal contraction into a global problem.

Folks, this is getting ugly. And the US needs to be thinking about how to insulate itself from European masochism.

Anatomy of a Euromess

who can say it better than Paul Krugman…

Most press coverage of the eurozone troubles has focused on Greece, which is understandable: Greece is up against the wall to a greater extent than anyone else. But the Greek economy is also very small; in economic terms the heart of the crisis is in Spain, which is much bigger. And as I’ve tried to point out in a number of posts, Spain’s troubles are not, despite what you may have read, the result of fiscal irresponsibility. Instead, they reflect “asymmetric shocks” within the eurozone, which were always known to be a problem, but have turned out to be an even worse problem than the euroskeptics feared.

So I thought it might be useful to lay out, in a handful of pictures, how Spain got into its current state. (All of the data come from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database). There’s a kind of classic simplicity about the story — it’s almost like a textbook example. Unfortunately, millions of people are suffering the consequences.

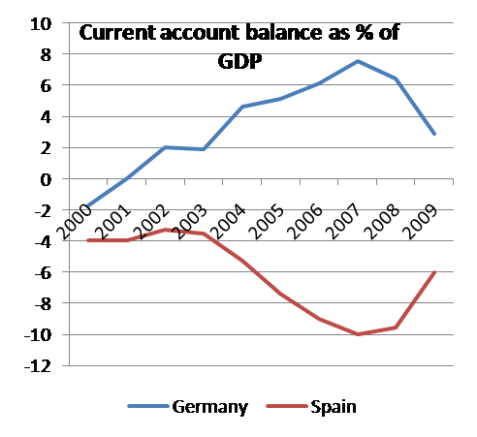

The story begins with the Spanish real estate bubble. In Spain, as in many countries including our own, real estate prices soared after 2000. This brought massive inflows of capital; within Europe, Germany moved into huge current account surplus while Spain and other peripheral countries moved into huge deficit:

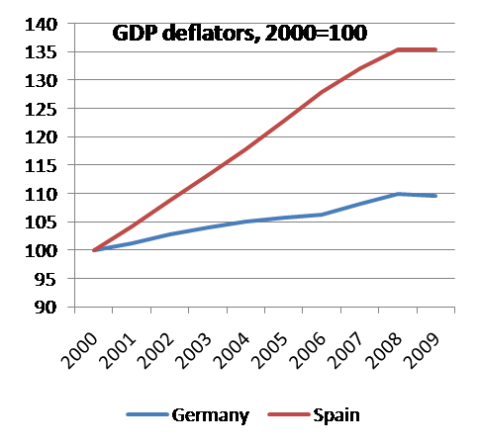

These big capital inflows produced a classic transfer problem: they raised demand for Spanish goods and services, leading to substantially higher inflation in Spain than in Germany and other surplus countries. Here’s a comparison of GDP deflators (remember, both countries are on the euro, so the divergence reflects a rise in Spain’s relative prices):

But then the bubble burst, leaving Spain with much reduced domestic demand — and highly uncompetitive within the euro area thanks to the rise in its prices and labor costs. If Spain had had its own currency, that currency might have appreciated during the real estate boom, then depreciated when the boom was over. Since it didn’t and doesn’t, however, Spain now seems doomed to suffer years of grinding deflation and high unemployment.

Where are budget deficits in all this? Spain’s budget situation looked very good during the boom years. It is running huge deficits now, but that’s a consequence, not a cause, of the crisis: revenue has plunged, and the government has spent some money trying to alleviate unemployment. Here’s the picture:

So, whose fault is all this? Nobody’s, in one sense. In another sense, Europe’s policy elite bears the responsibility: it pushed hard for the single currency, brushing off warnings that exactly this sort of thing might happen (although, as I said, even euroskeptics never imagined it would be this bad).

Am I calling, then, for breakup of the euro. No: the costs of undoing the thing would be immense and hugely disruptive. I think Europe is now stuck with this creation, and needs to move as quickly as possible toward the kind of fiscal and labor market integration that would make it more workable.

But oh, what a mess.

Eurozone Contraction

Here is a nice application of the Mundell Fleming Model with Flexible Prices

Falling Prices, Rising Unemployment Buffet Euro Zone

Use, Reuse, Recycle

A wonderful discussion of recent financial flows is provided by Brad Setser. The reserve flow dynamics can be worked out nicely with the aid of a Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rate Mundell Flemming model (Chapter 18 and 19). However, the Setser's piece does have some jargon, so if you have a life and dont want to slug though the IMF report (he criticizes) and his own theory, here are the key paragraphs:

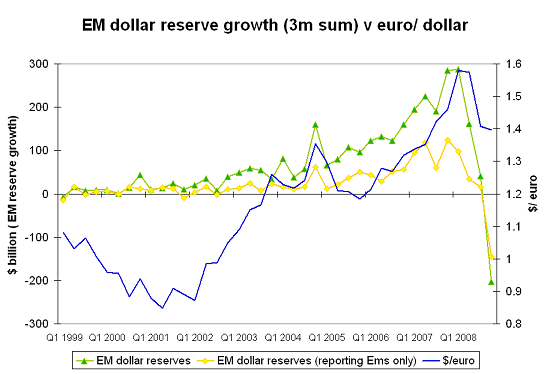

When the US slowed and the global economy (and the European economy) didn’t, private money moved from the slow growing US to the fast growing emerging world in a big way. The IMF’s data suggests that capital flows to the emerging world more than doubled in 2007 – and 2006 wasn’t a shabby year. Net private inflows to emerging economies went from around $200 billion in 2006 to $600 billion in 2007. Private investors wanted to finance deficits in the emerging world, not the US – especially when US rates were below rates globally. Normally, that would force the US to adjust – i.e. reduce its (large) current account deficit. That didn’t really happen. Why? Simple: The money flooding the emerging world was recycled back into the US by emerging market central banks. European countries generally let their currencies float against the dollar. But many emerging economies didn’t let their currencies float freely. A rise in demand for their currency leads to a rise in reserves, not a rise in [the price of the currency]. As a result, there has been a strong correlation between a rise in the euro (i.e. a fall in the dollar) and a rise in the reserves of the world’s emerging economies. Consider this chart – which plots [the 3 months sum of] emerging market [EM] dollar reserve growth from the IMF [official foreign currency reserve] data against the euro.

If the rise in reserve growth in the emerging world is a sign of the amount of pressure on the dollar, then the dollar was under tremendous pressure from late 2006 on. It central banks had broke – and lost their willingness to add to their dollar holdings then – there likely would have been a dollar crisis. A fall in inflows would have forced the US to adjust well before September 2008… Last week felt a more like the fourth quarter of 2007 than the fourth quarter of 2008. For whatever reason — an end to deleveraging and a rise in the world’s appetite for emerging market risk or concern that the Fed’s desire to avoid deflation would, in the context of a large fiscal deficit, would lead to a rise in inflation and future dollar weakness – demand for US assets fell. In some sense, the dollar’s fall shouldn’t be a surprise. Low interest rates typically help to stimulate an economy is by bringing the value of the currency down and thus helping exports.