Here is the bottom line on the Eurozone crisis. Is it massive government deficits, debt, political economy of austerity, default risk, or the absence of the promised $ trillion rescue package?

The answer is neither. The scariest prospect of all is that even if none of these issues existed, the crisis countries would have to work their way out of their crisis of competitiveness. Essentially they spent more than they produced, and to align their spending with their income, not only spending has to drop, but income has to rise. This can only happen if goods in crisis countries become more competitive. Here "competitive is simply an euphemism for "lower prices and lower wages." Krugman calls it the Elephant in the Euro and puts concrete numbers to it: wages in crisis countries need to fall 20 to 30 percent relative to Germany.

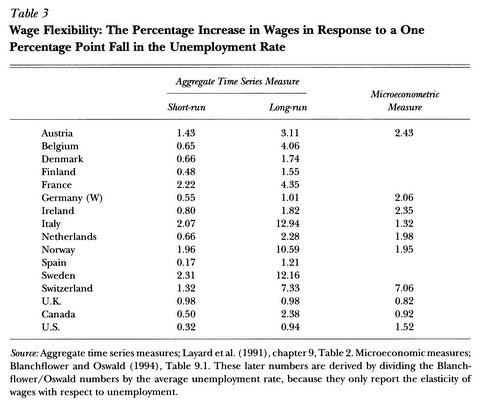

What does that really mean? Well, no none can really conjure up images of such a wage decline. But we do know that the country with the most draconian austerity adjustments, Latvia, saw its unemployment rise from 6 to 22 percent, causing a decline a meager decline in labor costs of 5.4 percent. One can only hope that European labor markets are more flexible and prices and wages adjust faster than in Latvia – but this is obviously wishful thinking.