(Re)Envisioning Orientalist North Africa: Exploring Representations of Maghrebian Identities in Oriental and Occidental Art, Museums, and Markets

By

Isabella Archer, University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

In

1832 Eugène Delacroix journeyed to Morocco

as part of a French ambassadorial

delegation to the Moroccan sultanate. The drawings, sketches,

paintings, and

notes Delacroix produced during and after his travels have had a

lasting effect

on the definition of what constitutes North African culture for both

nineteenth- and twenty-first-century consumers.

From the Denon salon of the Louvre Museum, where millions of visitors

view Women of Algiers

in their apartment, Delacroix’s painting

depicting

North African women lounging in a harem — to the markets of Tangier and

Meknes,

where tourists and Moroccans alike buy Delacroix-inspired street-artist

paintings and postcards, Delacroix’s Moroccan images and their

likenesses have

served as ‘authentic’ representations of Morocco for

generations.

How exactly did nineteenth-century European paintings come to constitute authentic representations of Arab culture? Authenticity, ever a loaded term, is in the context of this article the description awarded to a custom or object (such as a painting) that is widely considered to be accurate representation of a culture’s traditions and identity. More often than not, traditional items are antique or storied parts of a culture that have held a place of considerable importance in cultural expression for some time.

I do not attempt to determine what parts of North African culture are truly authentic, but instead I examine the ways people define authenticity, and what purpose definitions of authenticity are ultimately working towards in regards to North African cultures. I draw upon archival research and personal interviews and experiences to determine how authenticity is complicated by the observer and consumer’s preexisting-ideas and expectations about North African culture. By discussing the objects and objectives of traditional and/or Orientalist painting, how identity politics play into the work of post-modern artists from North Africa rejecting the Orientalist stereotypes and traditions of European painters, and the markets and marketing of North African art, I hope to explain why and how traditional art depicting North African culture and society is considered to be more accurate and authentic in many North African and Western opinions.

Authenticity is attained when a custom or object is perceived as being a genuine representation essential to the culture’s description, and is often linked to ‘traditional’ items or depictions of culture. Take, for example, the idea of an authentic Moroccan cuisine. Couscous is arguably Morocco’s most important dish; a wheat grain staple that is steamed and eaten with meat and vegetables. But couscous is more than a tasty foreign food. The meal holds a special significance in Moroccan culture as a family meal served each Friday and on special occasions. The value of a Moroccan couscous is one I learned firsthand from my host mothers in Fes and Salé, the latter having graciously taught me how to prepare the dish for a niece’s goodbye party. The process, though time-consuming, was well-worth the hours of preparation, and the couscous, thrice fluffed, and vegetables meticulously spiced and arranged, were a success. Eating the dish out of the family’s generational wooden couscous bowl was a Moroccan dining experience as authentic as any traveler could hope for.

The presence of an American fast food chain in Moroccan cuisine is at first glance a far cry from authentic Moroccan dining (or any authentic Moroccan experience, for that matter). Big Macs and McFlurrys are available anywhere, yet McDonald’s is immensely popular with its Moroccan clientele. The addition of the “McArabia” menu to Moroccan McDonald’s restaurants appear to authenticate the chain’s place in Moroccan dining, as the halal entrées — food prepared in way that is permissible to Islamic law — are cooked Moroccan-style to encourage diners to enjoy the mille et un saveurs (thousand and one flavors) of the new menu. Case in point: the Rabat cousins of my Salé host family insisted on taking me on a midnight run to McDonalds’, their favorite restaurant, for ice cream.

Deborah Root writes that “exotic images and cultural fragments do not drop from the sky but are selected and named as exotic within specific cultural contexts; certain fragments of a cultural aesthetic are selected and rendered exotic, whereas others are rejected.”[1] Given the popularity of both couscous’ and McDonald’s among Moroccans, which one is the “authentic” dish? When tourists come to Morocco, they want to sample ‘authentic’ native dishes, not the food they consume at home. Couscous is the authentic Moroccan meal because it is a dish that has been around for centuries, takes time to prepare, and is the center of the family meal on Fridays, a holy day in Morocco. The age and endurance of this tradition qualifies couscous as authentic. McDonalds, despite its popularity, is still regarded as American fast-food and as such, is rejected by tourists as an authentic icon of Moroccan culture — McArabia or no McArabia.

Isabella Archer

McDonald’s advertisement in Fes featuring the “Thousand and One Flavors” of McArabia, including “Saveur Tagine” and “Saveur Badnijane.”

For tourists, something authentic usually equals something exotic, something available only while traveling, even though a number of Moroccans enjoy McDonald’s and other non-traditional foods alongside their couscous. Despite the popularity of McDonald’s in Moroccan society, couscous is still touted as the authentic cuisine because of its traditional significance and history as a time-honored Moroccan custom among all Moroccans, often regardless of whether or not they like or eat the dish. The tendency to choose the traditional couscous over generic McDonald’s reflects expectations of what constitutes an authentic Moroccan cuisine then are frequently shaped by prior expectations on the part of the cultural outsider and cultural preferences, both real and perceived, on the part of the cultural insider. As such, a taste for the authentic, a construct that combines real and imagined history and perceptions of traditional culture, is likewise difficult to discern with respect to visual art.

Delacroix’s images of Morocco were and are today frequently considered authentic because the work was inspired by the artist’s journey to North Africa in 1832. The subjects of Women of Algiers in their apartment lounge in an opulent room bursting with the colors of intricate costumes, embroidered carpets, tiled walls, gilded mirrors, and a water pipe for smoking tobacco. These details are accepted as traditional and authentic because the costumes, carpets, hookah, etc. authenticate prior Western assumptions about Arab culture, drawn largely from literary sources such as A thousand and one nights.[2] Delacroix’s images took Western imaginings of the Orient a step further with their authenticating details and rich subject matter. As European interest in North Africa grew, artists and travelers would travel to the other side of the Mediterranean in greater numbers in search of exotic inspirations and experiences.

See Larger Image: Wikipedia

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in their Apartment, 1834. Musée du Louvre

Delacroix’s authenticity is not simply a European determination. Many people and cultural institutions in Morocco have a positive impression of Delacroix and feel the painter’s art made a lasting contribution to Moroccan culture by introducing Western audiences to the Arab world. The fact that a European artist’s depictions of North Africa had, and continue to have, a lingering effect on native perceptions of the traditional in visual art is significant both for supporting the assumption that Delacroix’s work is considered to be both accurate and timeless.[3] Paintings by local artists depicting traditional subjects, many of which modeled are after Delacroix’s famous paintings, can be found hanging in Moroccan households and restaurants. Artwork depicting traditional subjects and scenes is generally more popular than more modern, abstract art. The tourism industry in Morocco also provides many Moroccans — artists and others who do business with foreign travelers — with an incentive to promote traditional (and sometimes imagined) cultural products and experience for visitors seeking an “authentic” experience abroad based on Delacroix-like images of the Arab world.

In the early stages of my research, I met a Moroccan graduate student pursuing a degree in cross-cultural studies who was interested in dispelling stereotypes of the exoticized Arab world, specifically the harem fantasy and the ‘barbaric’ reputation of Berber peoples. Though friendly, it was only after I passed his pop quiz on significant anti-Orientalist authors and their tomes before he believed that my project was a critical study of authenticity and not just another Westerner telling Moroccans how to interpret their culture. While the need to defend my research felt unnecessary at the time, the exercise highlighted the importance of exploring the origins of Occidental misconceptions about the Orient.

European perceptions of Arab culture were already established at the time of Delacroix’s voyage. Deborah Root writes that, “Araby is the oldest enemy of the West and one of the first areas where Western artists and writers sought to represent cultural difference as such and to derive excitement from it.” Root writes that Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt in 1798, “ushered in a new interest in this part of the world on the part of the European, particularly French, artists, and set the stage for the extremely aestheticized treatment of later colonial adventures in Araby.” However, it was not until Algeria became a French colony, Root maintains, that the, “aestheticized and highly charged forms of ambivalence really took on a new life of their own.”[4] The French invaded Algeria in 1830, and the struggle for control over the North African territory would last fifteen years. The French’s bloody and brutal efforts alienated the colonizing power from their new North African neighbors, including Morocco.

In an effort to repair French and Moroccan relations, the French government sent an ambassadorial mission to Morocco in 1832 in an attempt to ameliorate the situation. It was the appointed ambassador to the Moroccan sultanate, Count Charles de Mornay who had the idea of adding an artist to the trip. Though the addition of an artist to the delegation was purportedly to make the trip more agreeable, the tradition of bringing artists on foreign missions was not unheard of—Napoleon brought with him a score of artists and intellectuals whose findings were published in the Description de l'Égypte, a detailed compilation of ancient, modern, and national Egyptian history.[5]

In his early thirties Delacroix had already achieved prominence for painting Oriental themes. His exhibition of The massacre of Chios (1824) and The death of Sardanapalus (1827) at the Salon, the official art exhibition of the Palais des Beaux-arts in Paris, solidified Delacroix’s reputation as a leading Romantic painter.[6] Delacroix’s journey to North Africa, however, would have a profound impact on his style and subject matter. Indeed, the voyage to Morocco would impact both the French Romantic movement in painting as well as audiences’ understandings of what constituted the authentic Oriental “Other” by bringing fresh and vibrant colors and life to the European art world.

See Larger

Image: Wikipedia

Eugène Delacroix, The death of Sardanapalus, 1828. Musée du Louvre.

The Arab world, long pitted against Christian Europe in the Crusades and Muslim conquests of Spain, was described in primarily negative terms, as an alien world of fanatical violence, oppression, and exotic mystery. Orientalism, the representation of Eastern cultures by Western scholars and artists, captivated European audiences. The death of Sardanapalus, which depicts the fall of the ancient Oriental tyrant, was among the Classical reproductions of the Orient that fascinated European audiences and provoked an interest in further study, research, and—in the case of the mid-nineteenth century French government—conquest of the Arab world. Root writes that, “The quality of timelessness and the presentation of Araby as a static, decadent entity well past its prime helped create an imaginary orient undifferentiated by place, time, and national or cultural specificity.”[7] This imaginary Orient is reproduced in The death of Sardanapalus and its violent, seductive, and timeless world of despots and damsels in distress reinforcing both previous assumptions about Arab culture and as well as the inherent backwardness and inferiority of the East. By casting the Arab world as ancient, backwards, and inferior, Christian Europe was by default the Orient’s superior, progressive, and modern antipode. The emphasis on the Sardanapalus story’s themes of violence and erotica, first immortalized in Lord Byron’s play and later in Delacroix’s immense oil painting, fed European perceptions about tyrannical Arab cultures.[8]

The death of Sardanapalus depicts the final moments in the life of the titular Assyrian ruler. His military defeated, Sardanapalus ordered his possessions destroyed and concubines murdered before he is to set himself on fire. Delacroix captures this scene in vivid detail: the painting, roughly thirteen by sixteen feet, shows Sardanapalus, a bearded man clothed in white, reclining on an enormous bed, watching the violence he has ordered unfurl. The rest of the painting is chaotic, violent, and highly sexualized: two women, one dead, the other at the edge of a knife, fall at the kings’ feet, their clothing ripped violently from their bodies. Dark, swarthy men with turbans, beards, and daggers slaughter a horse bedecked in riding finery. The men’s exotic complexions and dress contrast sharply with the pale and beautiful woman with a dagger at her throat in the painting’s foreground, a victim of primitive violence. Delacroix’s attention to detail is impressive: from the rich red folds of the bed sheets, spilling over the gold elephant bedstead like blood, to the intricate pearls, gold, and other jewelry scattered haphazardly throughout the room as a thick smoke billows in from the left side of the painting, Sardanapalus is a rich, beautiful, and terrifying work of art.[9]

The painting, obviously striking, aroused a degree of controversy during its exhibition at the Salon. The death of Sardanapalus awakened considerable criticism for its graphic, sexual carnage as well as technical execution and artistic merit.[10] While some historians argue that Delacroix used The death of Sardanapalus its attendant Oriental imagery as a means of expressing his graphic passions and feelings through non-Western subjects, I focus on how The death of Sardanapalus and other paintings by European artists both propagated Arab stereotypes and authenticated both the need for French involvement in the Arab world.

Before his trip to Morocco, Delacroix’s Orientalist work was informed by received knowledge and stories told by others. The death of Sardanapalus, though impressively and richly detailed, was based on Byron’s play Sardanapalus. Delacroix’s work stemming from his voyage to Morocco, on the other hand, was seen as an eyewitness account of the real, authentic Orient. The plethora of drawings, sketches, and notes from Delacroix’s Morocco journey, and the hundreds of paintings based on his lived, breathed experiences of North Africa, were a new and different strategy for defining authentic culture. Delacroix’s own view was that the journey to Morocco transformed the artist from a reproducer of prior assumptions of Arab culture to an observer and anthropologist; as an eyewitness to a foreign culture.

Arriving in Tangier in February 1832, Delacroix, dizzy with excitement, began making notes of all he saw. Writing to a friend, Delacroix stated that, “I do not want to let the mail go by, which goes to Gibraltar very shortly, without letting you know of my astonishment at everything I have seen…at this moment I am like a man who is dreaming and seeing things that he’s afraid will disappear.”[11] The light, vibrant colors and subjects of Morocco embodied the “beauty of antiquity” for the thirty-five year old painter, whose journals are peppered with hastily-executed sketches capturing snippets of Moroccan life.[12]

But no trip to a foreign country is without some small inconvenience or difficulty, and Delacroix’s enthusiasm would often be tempered by the obstacles and limitations he faced as a Western painter in a Muslim-majority country. “Little by little I adapt myself to the habits of this country,” he wrote, “so as to manage to draw many of these Moorish figures easily.” Islam generally eschews the practice of depicting humans and animals and art. While “arabesque” designs of flowers, geometric shapes, and curved lines are prevalent in Islamic art and architecture, the practice of producing realistic representations of God’s works is generally frowned upon. This frustrated Delacroix, who did not understand why his would-be subjects were resistant to his capturing their likeness in pencil or watercolor. Though Delacroix was eventually able to paint many Arab men and Jewish women, “They are very prejudiced against the beautiful art of painting, but with a few pieces of silver here and there appease their scruples.” The opportunity to sketch Moorish Muslim women proved evasive until the very end of his stay.[13] The challenges of drawing human figures in North Africa made Delacroix’s eventual visit to a harem in Algiers a monumental occasion, and the resulting work from this visit, Women of Algiers is a voyeuristic opportunity to see into the private space of women in Moroccan Muslim culture.

Or was it? A critical look at the circumstances of Delacroix’ harem visit provides some evidence that Women of Algiers, perhaps Delacroix’s most famous North African painting, is not as authentic as both Delacroix and his audiences, past and present, consider it to be. There is a certain level of disjuncture between the completed painting and the circumstances of the harem visit. Delacroix, anxious to see a harem during his voyage, pressed the matter throughout the journey but with little success. It was only in Algiers, a short stop at the journey’s end, that the painter had the luck of having his request honored by an Algerian family in the port city. Elie Lambert provides one rendition of the Algiers visit from Charles Cournault, a contemporary of Delacroix and curator of the Musée Lorain de Nancy:

To oblige Delacroix, they made a request to Mr. Poirel (the port engineer), whom they often saw entering the homes closed off to the outside. Thanks to his relationship with the natives with whom he worked at the Port, Mr. Poirel was in a position to provide this service. Finding a Muslim raised with Turkish customs who would admit Christians in to the interior of his harem was no easy thing to do. After many solicitations, Mr. Poirel obtained permission from a privateer of the Dey of Algiers that he [Poirel] could visit his home accompanied by his friends. Secrecy was promised on both sides.

The wife, warned by her husband, prepared pipes [hookah] and coffee, donned her finest dress, and waited, sitting on a couch [for their arrival].[14]

Lambert also provides de Mornay’s account of Delacroix’s visit to the harem:

The captain of the port would have heard from a renegade under him that Delacroix entered the house with him bringing painting supplies. Delacroix spent one day, and then another in the harem, falling prey to excitement, to a fever that sorbets and fruits could hardly soothe. The beautiful human gazelles got used to the situation and soon paid almost no attention to the painter hastily taking notes.[15]

Delacroix’s enthusiasm

may have been genuine, but the fact the household had been forewarned

about the

painter’s visit is evidence to the contrary.

The women dressed in their finest apparel were surely a sight to see,

but the fact of the matter is that their presence and poses were not in

fact an

accurate portrayal of North African life. Given this information, the

authenticity of Delacroix’s experience visiting the harem and the

authenticity

of Women of Algiers

must also be called into question.

Isabella

Archer

Lea Levy Benchenton, “Jewish Woman from Rabat,” Costumes Judeo-Marocaines en miniature, Museum of Moroccan Judaism of Casablanca.

The women, from their clothing to their poses, greatly resemble earlier sketches Delacroix executed of Jewish women earlier in the trip. My study of Delacroix sketches and visit to the Museum of Moroccan Judaism of Casablanca added additional credence to this theory. The Jewish museum — the only one of its kind in the Arab world — featured, among other wonderful treasures documenting the Jewish history and presence in Morocco and North Africa, a case of miniature dolls wearing Judeo-Moroccan period clothing. The exhibit, which had the dolls propped up on tiny cushions and surrounded by miniature teacups and carpets, looked like a Madame Alexander version of Women of Algiers. Though Delacroix’s writings on the harem visit would indicate the incident was seared into his memory for all time, Lambert argues that there is substantial pictorial evidence of Moroccan Jewish women as models for Delacroix’s painting. Many details of the harem women’s clothing, and their lounging poses and facial expressions seem to contain elements found in sketches executed of Moroccan Jews prior to the Algiers visit.

A large degree of this misunderstanding comes from the confusing expectations and definition of the term ‘harem’. In Western culture and societies, the harem has typically referred to an opulent closed space in a household where a patriarch’s wives or concubines, forbidden to leave the confines of the harem, are guarded by eunuchs as they wait for their masters’ return. This image, first featured in the translation of A thousand and one nights, has been perpetuated for centuries afterwards in paintings, film, and advertising. In fact, the word ‘harem’ comes from the Arabic root haram (forbidden) actually refers to the traditional women’s space or resting quarters in a household. Though this space is private, and generally closed off to men who are not family members, the harem is not an exclusive women’s sanctuary, children and other family members are invited as well.

Given this more factual understanding of the harem space, it becomes easier to understand how the degree of authenticity of Delacroix’s ‘harem’ visit and his subsequent painting Women of Algiers is brought into question. Delacroix may have believed he had finally penetrated the sacred harem space, but the “harem” had been prepared for his visit and was arguably more of a rehearsed spectacle then a true show of Muslim women in their natural environment.

My own experience in the “harem” space provides an interesting comparison to the harem visited by Delacroix and the harem image depicted in Women of Algiers. I recall my first day in Morocco when my Fassi host mother picked me up from the Arab Language Institute in Fes dressed in a leopard-print jellaba (a traditional full-length Moroccan robe with a hood), high heels, and tan scarf tied over her hair. Arriving at their house in the traditional old city, we brought my bags into the sumptuously decorated living room with long couches, pillows, flowers, mirrors, and a beautiful rug stretching across the tiled floor, an image that could have been right out of Orientalist imagination. The Women of Algiers setting was disrupted when my host mother removed her jellaba and began cooking lunch, tying an apron over the pajamas she wore underneath her traditional outerwear.

As my days in Fes turned into weeks, the would-be harem setting disintegrated. Though my host mother did not work outside the house, she was nonetheless a busy woman, shopping every morning, cooking and baking fresh and cleaning the house and visiting friends and family members who lived in the medina. I would accompany her on many of these visits, where once we arrived the jellabas would come off and the women would cook and socialize together in their pajamas or exercise clothing.

Both of my host families, in Fes and Salé, showed me photos and video from special events where kaftans, richly detailed traditional dresses worn for baby showers, engagement parties, and weddings, were worn. Kaftans were so expensive and fragile; my Salé host mother informed me, that they were only used for those occasions and kept folded and safe the majority of the year. So when asked if I would like to try on a caftan, I jumped at the opportunity. It was only in retrospect, poring over the poses in the photographs I took with my host sister in Salé, that I realized I was in danger of becoming an Orientalist traveler myself, a Delacroix 2.0. My experiences living with Moroccan families were opportunities to immerse myself in a different culture and participate in an exchange of language, ideas, and friendships, but my position in the household was still that of a guest, and a foreign guest at that. In my photographs from Salé, I am wearing an ‘authentic’ Moroccan caftan in an ‘authentic’ Moroccan household with my ‘authentic’ Moroccan host family, but it is my presence as an outsider that constituted the ‘special occasion’ for us to be wearing such ceremonial clothing and taking photographs. My experiences in Morocco allowed me to experience many traditional aspects of Moroccan and Muslim hospitality in their most authentic setting; however my presence as a visitor and cultural outsider nonetheless also played a significant role in the creation of authentic experiences outside my families’ regular schedules so as to give me an ‘authentic’ understanding of Moroccan culture and life. While of these experiences, stage-crafted for my benefit, were a unique opportunity for cultural immersion, the fact that such moments were usually outside my families’ real day-to-day lives calls into question their characterization as truly authentic.

While Delacroix’s visit to a Muslim Moorish household may have been a real and authentic experience, the artists’ understanding of his trip and subsequent depictions of his experiences is complicated by the fact that his authentic experiences, like mine, were a very real part of North African life. A critical realization of the circumstances surrounding these cultural experiences, however, is mitigated by the knowledge that certain images of North African culture are presented, frequently out of context, for the outsider’s consumption. Orientalist stereotypes are based on a presumed Western cultural authority, and is coupled to the longstanding idea that that which is traditional is authentic. North African culture can, and frequently is interpreted from a plethora of perspectives — by artists of differing national and ethnic origins and agendas.

To see a famous or much-studied work of art in person is a tremendous opportunity; one I had been looking forward to for months when I arrived in France in July 2009. However, as I prepared myself for an important moment in the research process—viewing and observing Delacroix’s Women of Algiers and The death of Sardanapalus, I came upon a curious sight in the Louvre Museum.

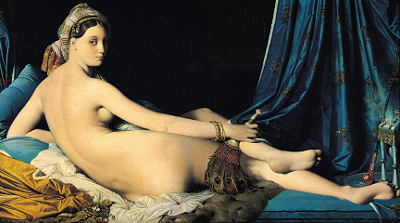

En route to the Delacroix works, I stopped to review another famous painting, Jean-Dominique Ingres’ Grande odalisque. The likeness of a young Oriental chambermaid or odalisque, completed in 1814, is frequently subject to criticism because of the figure’s anatomically incorrect proportions. The nude’s spine is abnormally long, as are her limbs. Additionally, Ingres’ depiction of his subject as an odalisque was an unusual choice for the Neoclassical painter, a discipline typically concerned with depicting classical themes from Western literature, art and culture. Finally, the odalisque’s fair-skinned and Occidental appearance is rendered exotic only by her foreign accoutrements.

See Larger Image: Wikipedia

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Grand odalisque, 1814. Musée du Louvre.

The painting’s exotic details, from the plumed feather duster and hookah pipe, to silk drapes and the nude’s languid pose on the divan, validate an otherwise inappropriate subject. Elderfield notes that “topographical details gave credibility to representations, authenticating even the most extraordinary pictorial inventions.” [16] Ingres’ interpretation of the odalisque is certainly extraordinary. The painter never visited the Orient, acquiring his details from travelers’ stories and pre-existing ideas about the Orient as a timeless exotic cadre for his subject. Painting subjects in the nude was typically reserved for classical paintings of Western antiquity, hence without the Oriental odalisque pretense, the nude, already resembling a young European woman, would be entirely unsuitable for public display.

Although the artistic merits of the painting and its interesting history make Grande odalisque a stopping point on most tours, the odalisque’s captivating gaze and curves seem to attract a sizeable chunk of visitors’ attention as well. I witnessed a young man take a particular interest in certain aspects of the painting, namely, the breasts and bottom of the odalisque, going as far to photograph the odalisque’s would-be private parts with excitement, blocking others’ views to capture the painted flesh in photographs.

While each viewer is entitled to his or her own interpretation of enjoyment and consumption of art, this young man’s behavior was nonetheless an indicator that the sensual nudity of the odalisque was a reason to take pause in front of the canvas. I was heartened to hear the Louvre audio guide dismiss the notion that such art works were realistic representations of people or places, instead lecturing on the paintings’ controversial history and artistic merits, but for several viewers (including the aforementioned gentleman) I observed, it appeared as though it was the odalisque’s sensuality, depicted in a fictitious Oriental setting so as to be appropriate for nineteenth-century viewers, that continues to give a number of tourists reason to pause.

Isabella

Archer

Tourist at the Louvre, 2009.

Whether drawn in by

artists’ use of color, painting technique, exotic locales or sexualized

subjects, the images of women and the Orient in paintings such as

Grande odalisque

and the Women of Algiers

have captivated artists and

audiences for almost two centuries. Delacroix once wrote he would like

to come

back in a hundred years and see what the public remembered of him and

his art

works. [17]

The artist would, no doubt, be surprised to see how Women of Algiers

and

his other works have influenced perceptions of foreign women for many

artists

and scholars over generations.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a voyage to North Africa was becoming a rite of passage for a number of artists in search of new material for artistic inspiration and innovation. The philosophy of primitivism, which advocated an escape from modernity via the discovery of non-Western cultures and a ‘simpler’ existence, was a growing movement in the art world. In seeking inspiration from the primitive or “naïve” worlds and works of non-Western artists, Occidental painters hoped to produce original art works capturing the world of the Oriental Other.

When Henri Matisse journeyed to Morocco in 1913, he had a number of predecessors in the increasingly international city of Tangier. Though Matisse, considered the leader of the Fauvist movement, had some reservations about Delacroix and his Romantic interpretations of North Africa, he nonetheless expressed admiration for the precision of Delacroix’s work. Indeed, Matisse’s depiction of North Africa — from his use of color in vibrant landscapes, city scenes, and portraits of Moroccan men and women — would earn him the title of the “modern counterpart” of Delacroix from some historians. [18]

Schneider writes that what Matisse held against Delacroix was “not so much his work as those twenty generations of painters” who, impressed by Delacroix’s work, came to Morocco to imitate their predecessors’ art work and pick up “ready-made pictures” in Morocco. [19] The idea of traveling to the North Africa only to replicate the same scenes and details of a predecessor’s work held little appeal for Matisse, for whom creating original and authentic works reflective of his own journeys and observations in Morocco was tantamount.

Matisse’s twentieth-century paintings of Morocco are remarkable depictions of the Arab world bathed in color and light. Colin Rhodes writes that Matisse’s odalisque scenes “are pictured in the familiar decorative style of his images of women…but it must be remembered that his was a style modulated by the influence of the artist’s experience of African sculpture and, more particularly, to his interest in the decorative possibilities of Oriental carpets and patterned textiles.” [20] Thus, Matisse’s use of the Oriental woman—frequently an odalisque—is less about depicting the odalisque or her culture so much as experimenting with native art forms on canvas.

When a painting’s focus is on aesthetic detail at the expense of the subject and content, it may become necessary to call the authenticity of the work into question. Matisse’s interest and experimentation with a foreign culture’s art and technique indicates the advent of the primitivism art movement. Native art, constituting everything from carvings, masks, and statues to arabesque décor and patterned cloths were sources of simple, natural, and moral inspiration for a number of Western painters.

See Larger Image: San

Jose State

University

Henri Matisse, Odalisque à la culotte rouge, 1921. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

The nineteenth-century

Orientalist obsession with details appears to continue to influence the

work of

twentieth century painters as well, as evidenced by Matisse’s attention

to the

detailed chambers and clothing in his many odalisque paintings.

Matisse’s focus

on African sculpture and textiles alone is not grounds for criticism,

however

the apparent lack of interest in the human subject and the consequences

of this

cultural depiction demonstrate a latent, if not manifest absence of

interest in

the painting’s subject.

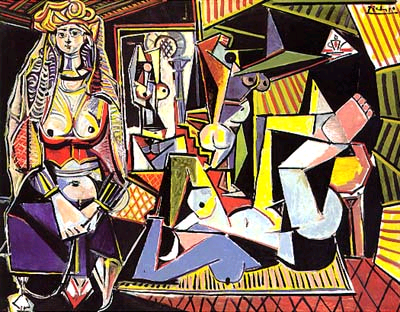

It is helpful to compare Matisse’s work to another master whose use of Oriental detail in his painting demonstrates an attention to detail, yet comprises a very different reinterpretation of the Orient and Delacroix’s work. For Pablo Picasso, using Delacroix’s Moroccan scenes and spaces were a means of personal expression and experimentation. Martine Antle describes how surrealists in Paris, including Picasso, were encouraged to “rethink the Orient” because of the presence of the self-taught Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine. Mahieddine, whose work centers on female subjects, employs a calligraphic style of painting in her work and using intricate decorations and Arabesque patterns resulting in works filled with “intricate decorative and repetitive rhythmic patterns reminiscent of Arabic calligraphy, Islamic art and oriental carpet.” [21] This combination of historical artistic traditions to showcase female subjects from a fresh and non-Orientalist perspective is a strategy that ought to elude Western categorizations of her art. Mahieddine, was frequently labeled as ‘exotic and’ categorized by many Western critics as employing a “naïve” or “primitive” style. Some critics went as far as to define her work in the context of the original source of Orientalist fantasy— A thousand and one nights. [22]

See Larger

Image: The

Metropolitan

Museum

Baya

Mahieddine, Femmes

portant

des coupes, 1966. Institut du Monde Arabe

Picasso’s interpretations of Oriental subjects, however, were not subject to such categorization. Picasso’s many renditions of Women of Algiers are painted in the cubist fashion, represented from a variety of perspective, changing shape, color, and form to create a set of paintings differing greatly from one another. Picasso’s motives for reconfiguring Women of Algiers and ultimate purpose could be interpreted from a variety of perspectives: his work, though replicating a predecessor’s painting, is considered neither primitive nor naïf; it is a complex and uniquely authentic interpretation of a subject from a series of different angles and perspectives.

See Larger Image: Art

Knowledge News

Pablo Picasso, Women of Algiers in their apartment (Version O), 1955. Musée Nationale d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou.

Aesthetic detail and artistic innovation are each important qualities of creative expression; however, content and perspective are integral for a painting to qualify as an “authentic” depiction of a given culture. The works of Matisse and Picasso are those of masters, but their use of the Orient, be it for artistic originality or experimentation, belies the importance of understanding the content and message that is so critical in works depicting people and traditions. Despite the critical categorization of her work as primitive or naïf, Mahieddine’s work nonetheless challenges viewers to examine her subjects from a uniquely female, Algerian perspective. Now, a new set of artists and scholars began using the work of Delacroix and other Orientalist painters along with their own original works to express ideas and showcase opinions about authenticity — but in a very different direction.

Antle writes of Mahieddine’s drawing of the female eye that her representation “of the female eye in the shape of an inverted H suggests an alternative mode of seeing and of reading, an alternative to art produced by vanguard male artists and to colonial representations of Oriental women.” [23] These unique details, hidden in seemingly traditional designs, are a step away from Orientalist attempts to conform to the viewer’s expectation of “authentic” by expressing a new female perspective via a traditional writing technique in painting.

Mahieddine’s work is one of the first examples from a growing pool of artists, and especially women, reclaiming their identity and redefining the authenticity of Orientalist fantasies and stereotypes about Arab cultures via new details and points of emphasis and reference in their work. Where the focus on aesthetic details in the work of Matisse and Picasso superseded a focus on the subject content of their art, in many contemporary works, details—traditional and modern—play an important role in creating a new definition and standard for authenticity in art.

In 1967, Assia Djebar, an Algerian author living in France, wrote a collection of stories carrying the same name as Delacroix’s famous painting. [24] According to Mildred Mortimer, a critic for the French Review, Djebar chose the title “Women of Algiers in their Apartment” for her stories because she felt the painting was a valid symbol for representing the women of Algiers today. Her interpretation of why the painting is a valid symbol for Algerian women, however, differs greatly from that of Delacroix and his contemporaries. Djebar, a woman with a “firm commitment to depicting the psychological and sociological complexities of women’s positions in a Muslim society in transition,” uses the Delacroix painting, which also portrays women in an enclosed space, as a metaphor for which the situation of Algerian women in a contemporary setting is enclosed by society and stereotypes. [25]

In the first scene of the “Women of Algiers” novella, a surgeon, Ali dreams he is helplessly looking on as a woman is tortured in front of him. The fact that the torture cannot be avoided in a dream is a sad echo of real-life Algeria during the mid-twentieth century and an insinuation that masculine protection is not enough to guard a woman during her lifetime. Sarah, Ali’s wife, was in fact tortured during the Algerian war, and only finds consolation with her female friends, not a husband who is unable to understand her situation. Djebar’s use of Women of Algiers sends a very different message about the painting, and its relevance to the Arab world today, using the painting to showcase the shortcomings in the Arab world. The conversation with Delacroix’s painting is recognition of both the enduring legacy of Orientalist perceptions about Arab cultures as well as the ongoing “cloistering” of North African women in a figurative “apartment” that represents the limitations upon women that Djebar perceives to persist in North African and Muslim societies today.

In contrast, Houria Niati makes a strong declaration about the inauthenticity of Delacroix’s work in her painting No to torture, a thoroughly post-colonial and post-modern reconstruction of Women of Algiers. For Niati, a contemporary Algerian artist who grew up in Algeria and lives in France, the title of the work is an affirmation of independence and a call to the viewer to not accept the torturous treatment of female subjects in Orientalist fantasies of the other. In the exhibit, Niati rejects the idea that Delacroix’s Women of Algiers is an authentic replication of North African women or culture.

Houria Niati, No to torture, 1982. London

Niati depicts the figures, stripped of the clothing, jewelry, and other details that define the setting of the painting as a North African harem. Devoid of any detail, the figures are painted in the same positions as Delacroix’s Algerian women, but in bright bold colors, their faces obscured by brush strokes. The effect is startling, and the objectification of the women, who look as though they are being viewed by a heat sensor, faces obscured by a large X, a cube dripping paint, and a vortex of muddled colors, is evident. In Orientalist art, details served the function of authenticating the painting, but here, the lack of detail that dramatizes the women’s position and reinforces Niati’s message to her viewers.

Her painting represents the female bodies subject to Oriental voyeurism, but also pays homage to the more recent torture of women tortured during the Algerian war for independence in the late fifties and early sixties. Niati’s bold, raw painting style reveals the harsh objectification of the women for the viewer’s “consumptuous gaze,” the use of oil paint mixing high art with a powerful political message. [26] Any claim of authenticity in the original Delacroix is rejected by Niati and her four female figures, exposed yet obscured by the bright defiant brushstrokes that draw the viewer in to No to torture yet disable them from fully penetrating the painting. “Although Niati maintains the sensual relaxed poses of Delacroix's figures,” Rogers writes, Niati “interrupts the viewer's ability to consume, passively and comfortably, the bodies of the Algerian women as in Delacroix's work. The viewer desires to visually dwell in the lush array of colors in No to torture, while simultaneously experiencing a sense of unease as a result of Niati’s artistic act of violence.” [27] Niati also demonstrates a radical opposition to the Orientalist hierarchy in Women of Algiers with her use of color. Her opposition to the racial coding and colonial hierarchy is brightly signaled by her re-coloring the black slave who exits to the left in Delacroix’s painting a vibrant blue. This gesture gives her work the added dimension and sensitivity to the many ways in which Algerian women were and are tortured at the hands of former colonial powers, societal demands, and longstanding stereotypes, and lends an additional spark to the Niati’s heated artistic dialogue with Delacroix and her predecessors.

Similarly, a recent exhibition at the Lille Musée des Beaux-arts, Miroirs d’Orients, encouraged attendees to trace the evolution of Orientalist conceptions about Arab cultures themselves and compare eighteenth century tableaux to twenty-first century reinterpretations of the same themes. “Starting in the 1850s,” the guide to the exhibit explains, “painters, draughtsman, and photographers went to North Africa and the Middle East, where they portrayed what they felt was likely to please the European amateurs d’Art…in so doing, they set in motion a version of the Orient that remains in our collective consciousness yet today.” [28] In an attempt to challenge this vision, Miroirs d’Orients juxtaposes sketches, paintings and photographs by nineteenth century European artists and travelers in search of the exotic across the Arab and Muslim worlds with contemporary anti-Orientalist modern artworks by artists from all over the world.

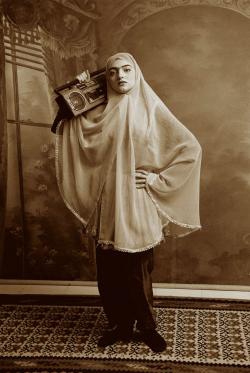

The goal of Miroirs d’Orients is to have the viewer, armed with this knowledge, walk through time, from the early 1800s to today, and see how the Orientalist fantasies about the Middle East and North were first constructed and how they have since been deconstructed. “Artists today,” the exhibition states, “have reclaimed these snapshot images in an attempt to create a contemporary Orientalism.” [29] In their work, done in a variety of media including painting, drawing, photography, and multimedia presentations, artists—of Morocco, Iran, Japan, European, and American origin, among others—make an effort to reverse the themes present in nineteenth century Orientalist fantasies about the “Other.” “Those formerly observed thus become the observers,” the exhibition concludes, with the artists, working in a “current context where world cultures meet…restate their true and imagined identities as seen from the outside.” [30]

The “Orient” of Miroirs d’Orients spans from North Africa to the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and the Middle East, and Iran, and the exhibit begins with a selection of sketches from Delacroix and ethnographic drawings from other European travelers and artists — Gustave Guillaumet, Edward Dufen, and Emile Marquette, among others. The exhibit also contained a number of Orientalist photographs, said to confirm the images of the Orient described in the writings of Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Maxime du Camp. The popularity of these images led to the emergence of photographic workshops across the Middle East and North Africa, including one (the 1867 Maison Beaufils), which attracted a number of photographers, of both European and Arab nationalities, who then traveled around the Orient photographing and further disseminating the postcard-like images which were sold both individually and projected during public lectures, increasing their visibility among European markets.. Both the use of photography, which ‘authenticated’ Orientalist images with black-and-white scenes captured on film, and the popularity of post cards of North African women and landscapes, would cement Orientalist images in the European sub-conscious over the following decades.

After passing through a collection of sketches and photographs from the nineteenth-century Orientalist greats, Miroirs d’Orients attendees enter a second large hall running adjacent to the Orientalist artworks that contains post-modern recreations and responses to the preceding room’s pieces. Shadi Ghadirian, an Iranian artist, confronts the timeless, docile identity imagined for her and other Oriental women in a series of photographs from the “Ghajar Series.” For this set of photographs, Ghadirian dresses her female models in traditional Iranian garb and poses them either sitting or standing in front of ornate decorated backgrounds after the 19th century style of photographs from the Ghajar period in Iranian history, when photographs were legally permitted. The subjects, photographed in sepia, would recreate the two-century older images if not for Ghadirian’s placement of contemporary props such as a boom box, soda can, or vacuum cleaner. The effect of these items in each photograph is startling, creating a sort of time warp that shatters the attempted “timelessness” of the Oriental woman. Though the street-cool pose of the woman with the boom box and others may amuse at first glance, the overall effect on the photograph and the viewer’s experience is a powerful, and Ghadirian’s combination of past and present details in her portraits of Iranian women is reflective of the position of women from the “Orient” in between popular culture and day-to-day life.

See Larger Image: Saatchi Gallery

See Larger Image: Saatchi Gallery

the Ghajar series. 1998-1999.

Ukrainian artist Anton Solomoukha also signals a change in Western perceptions of Orientalist authenticity in his painting The Turkish bath, modeled after an 1862 painting by Ingres’ Grand odalisque. Although Ingres’ The Turkish bath spent most of its life in private ownership, the 1862 painting is nonetheless an important work in Orientalist art. Ingres, however, who painted The Turkish bath towards the end of his life, had never visited the Orient, instead copying details from travel letters and others’ accounts into his work as a pretext for painting the nude female.

See

Larger Image: Wikipedia

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The bather of Valpincon, 1808. Musée du Louvre.

The main figures in the painting are all based on earlier Ingres nudes, such as The bather of Valpincon, and the anatomical incorrectness of the bather with her arms overhead echoes the anatomical incorrectness of the Grand odalisque. The lack of originality in Ingres’ painting, along with his thinly-veiled attempt at using the exotic to depict women of otherwise European appearance in sexualized, passive poses, makes The Turkish bath a target for many feminist and anti-Orientalist artists and authors.

See

Larger Image:

Black Square Gallery

Anton Solomoukha, (Detail), The Turkish bath, 2007. Palais des Beaux-arts, Lille.

Solomoukha’s piece

combines photography and painting, is a post-modernist recreation of

Ingres’

original bath scene. Like Niati, Solomoukha’s art seems intent on

showcasing

the women in the painting as the Orientalists really saw them, but

instead of

obscuring the details, Solomoukha’s clear-cut images of the women,

their flesh

and accessories standing out against the dark background, lustily

exposes the

figures’ bodies to the audience, and without the pretense of an

Orientalist

décor. Coward writes that “The function of the detail,” in Orientalism,

“in

particularizing the setting, is to reinforce the drama that completes

the

setting,” a technique Solomoukha employs in his twenty-first century

Turkish

bath. [31]

The pink tights and tattoos adorning the models, along with the

“traditional”

head scarves worn by a number of the women refute the supposed

timelessness of

the models, and the in-authenticity of the supposedly “Turkish” bath is

exposed

as a borderline pornographic playground.

Works like Solomoukha’s, and a number of other anti-Orientalist pieces in the Miroirs d’Orients exhibit by artists of European and American origin, signal a shift in Western artists’ attitudes about painting Oriental subjects. In exposing the fallacies of the nineteenth-century masters’ works, the artists in the exhibition become post-Orientalist artists, seeking to depict a more realistic and contemporary vision of the Orient, from Morocco to the Gulf and surrounding lands and cultures. Artists like Solomoukha, who attack the search for authenticity by a European predecessor, indicates the movement to debunk Orientalist stereotypes is not limited to Arab and Muslim artists, but all persons who believe in fair and accurate representations of different cultures.

However, the very presence of non-Oriental painter in a forum giving Orientalist subjects the opportunity to react and represent their identity is in itself somewhat problematic. Does this foreign presence, though sympathetic to the position of Orientalist misconceptions of the other, continue to depict and “speak for” the Orient like their predecessors? As the discussion about authenticity shifts to a discussion of effectiveness and representation, a new set of questions arise. Though works such as Solomoukha’s and Ghadirian’s may be more “accurate” depictions of the Arab world then odalisques and harems, the enduring popularity and visibility of Orientalist art from Paris to Tangier raises questions the effectiveness and desirability of both Orientalist and contemporary art works. As the discussion of authenticity shifts to one to include the (in) tangible value of art for its audiences and consumers, the taste of the consumer, from North Africa and Europe, become a critical factor in what depictions of North African art are indeed authentic.

My first morning in Morocco, while attempting to revive myself with a breakfast of bread, jam, and sugary sweet mint tea, I was surprised by a familiar image in the otherwise unfamiliar hotel dining room. Orientalist posters, images used to promote travel and commodities such as soap and oranges with turbaned men and desert sunsets, hung on every wall of the room, promising an exotic winter or spring in the North African products was only a plane flight or palm olive purchase away.

The posters, which I studied previously as examples of Orientalist imagery in marketing, promote tourism and the purchase of certain commodities as exciting, and exotic attractions yet not entirely reflective of “authentic” Arab societies. I soon grew accustomed to seeing these posters on display in many hotels and restaurants, as well as for sale along the main thoroughfares in the touristy parts of the medina. But the posters would surprise me outside Morocco months later at a meeting in the chair’s office in the Department of Asian studies. The sight of the same Air France poster of a North African man looking at a plane (flying suspiciously low to Marrakesh) seemed to me an indication that these posters, first printed in the 1920s, continue to play a visible role in advertising a voyage to the Orient as well as specific images of North Africa.

Air France Afrique du Nord, 1958, Air France.

Preferences for traditional art are based upon aesthetic appearance and style, as well as the authenticity of the subject or content of the work. Orientalist posters depicting traditional North African culture, as advertisements or as a souvenir of one’s journey and/or experience, are a popular memento to remember the Maghreb. But what do these purchases of posters and art, be they traditional, commercial, or avant-garde, communicate about which styles of art are truly authentic representations, and how are they influenced or complicated by cultural and commercial tastes and expectations of the “Other?”

Interviews with artists, curators, and travelers produced a variety of perspectives and opinions. For some purveyors of art from Europe and the Western world, as well as from North African, Orientalist renditions of an imaginary North Africa are considered a valuable, detailed and accurate homage to Moroccan culture. For others, post-modern interpretations of Moroccan culture via art were just as valuable; their aesthetic qualities superseded the necessity for recognizable contention. The variation in opinions and perspectives reveal the conflict between depicting what one truly believes to be an authentic representation of North African culture with viewer expectations.

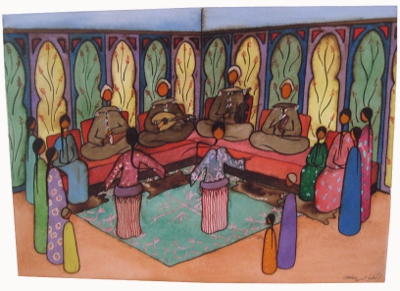

Right around the corner of the Casbah in Tangier, sitting high above the Mediterranean, is a small specialized art boutique where a number of paintings depicting traditional Moroccan culture are on sale daily. For Mohammed Chaara, the gallery’s host and a contributing painter, the preservation and presentation of Moroccan subjects in traditional settings is a means of preserving his culture as well as making his living selling images that tourists want to see on their trips to North Africa. Chaara, a gym-teacher turned artist, is based in Tangier and exhibits his work in North Africa and Spain. Chaara describes his style as “naïf,” or “native,” and paints a variety of traditional subjects using watercolors, ink, and broue de noix, a substance used by carpenters to finish wood that produces a rich brown-black color and marked texture on canvas paper.

Chaara first saw Delacroix’s artwork in books at the Institut Français and said he was fascinated by the French master’s work and depictions of Morocco, which he feels capture Morocco very accurately and in detailed color. Like Delacroix, Chaara said he paints Morocco because his country inspires him, and although Chaara’s style of painting, using the broue de noix to paint his figures in an almost calligraphic simple form, his use of color and arabesque decoration echoes the light and detail of the Delacroix work he so admires. Indeed, browsing through Chaara’s web site, one can read a number of comments from visitors Moroccan and foreign commenting on the way his paintings capture the light of Larache, another seaside city, practically echoing the praise of earlier Delacroix critics.

But where Delacroix’s paintings are notable because they are an eyewitness account of the people and country he visited, Chaara paints from memory in an attempt to preserve Morocco’s meaning customary or established practices such as attending religious school, traditional dances, and outdoor market scenes. When asked why he prefers traditional subjects, Chaara responded that he is interested in painting the aspects of Moroccan culture he worries may become disposable or disappear. “Art,” he says, “is the food of the soul and spirit, and gives us assurance of existence,” [32] For Chaara, his art is a way of preserving traditional culture and emphasizing its importance in the lives of Moroccans today, and painting the streets and figures in traditional clothing is Chaara’s way of guarding the memories of traditional Moroccan culture that may disappear in a globalized world.

Isabella Archer

Mohammed

Chaara, Untitled, 2007.

The relationship between

memory and authenticity in Chaara’s work is important because he draws

on both

his own cultural memories of Moroccan traditions as well as Delacroix’s

artistic record of his country’s customs.

Chaara’s memory of things that he himself did not experience is thus

supplemented, and to a certain degree authenticated by the artistic

“proof” of

Delacroix and other European painters’ earlier tableaux.

The desire to preserve traditional culture is a sentiment echoed in many Moroccan households. While studying at the Arabic Language Institute in Fes, a classmate approached me with the following story: her host family, like many Moroccan families, owned a variety of paintings depicting Arabs on horseback, roaring battle cries across paint and pastel, scenic Moroccan landscapes and gates, or women in the home, frequently lounging in their finest apparel. Such paintings are popular purchases in the medina markets, or souks, where one artist stall after another sells both original artworks and imitations of more famous Orientalist paintings as well as prints and postcards of traditional Moroccan scenes. “I asked my host dad why we had those paintings, and if they were supposed to represent anything or anyone in particular,” my classmate told me, “and he said that the people weren’t their family, they were their imaginary history, a representation of Moroccan culture, that he was proud of.”

My classmates’ understanding that these traditional and supposedly authentic pictures were of an imagined history is a testament perhaps to her education as a graduate student in Middle Eastern studies. However, her observations are also significant for her recognition of the fact that paintings as an ideal that while not really existing in real life, are nonetheless an idealization of a cultural past pieced together by cultural memory and depictions similarly idealized by artists in earlier generations. And as the market shows us, there are a plethora of reasons as to why a romanticized version of history and culture might be preferred by Moroccan and foreigners alike.

Globalization and an increasingly international tourism industry encourages the manufacture of traditional items as souvenirs, and this commodification of traditional culture serves to both preserve what Chaara views as disappearing traditions as well as provide him and his family with a living. He is able to preserve his culture as well as make a living depicting what tourists want to see, and is firm in his belief that art is the “root to mankind” and contends that although both Moroccans and tourists purchase his work, foreign buyers make up a greater percentage of his customers. [33] This pattern, Chaara says, is neither unusual nor Orientalist: “The tourists come to enjoy Moroccan culture,” he says emphatically, “we see cowboys in America; we don’t want to find them in Morocco!” [34] Tourist or traveler, most individuals travel to experience a place, environment, people, and culture that is unique and different from their own. Just as foreigners in Morocco eschew McDonald’s for a local couscous, in choosing souvenirs with which they want to remember their trip by, they opt for that which is most different and exotic, and preferably something they have experienced themselves. Opportunities for first-hand immersion in North African culture are available to tourists. From camel treks to cooking classes, with language lessons and art, rug, and pottery purchases squeezed into insider tours that allow outsiders to bring traditional treasures from the “inside” home with them.

Although the general preference in art appears to favor traditional images over contemporary, this preference is not without is not without exception. Indeed, a number of art galleries in Morocco showcase modern interpretations of North African culture via paintings, sculpture, and mixed media. I visited a number of museums from Tangier to Marrakesh where contemporary, abstract works by Moroccan artists were for limited-time-only display and sale exhibitions.

One of these galleries, the French-owned Galerie Delacroix in Tangier, proved to be of particular interest for its exhibition Tanger: rencontre des cultures, the first annual exhibition of its kind by the Association Tanger des Arts Plastiques in late June 2009. Mohammed Chhibi, gallery technician at the Galerie Delacroix, explained the origins of the festival as well as the mission of the Galerie and his thoughts about modern versus traditional Moroccan art. Tangier, Chhibi explained, is an international city, one that has served as the meeting place and source of inspiration for scores of artists, Delacroix of course included. In choosing “Delacroix” as the gallery name, the institution sought to invoke a high standard of artistic talent that resonated with the city and its significance in art history.

But although the name “Delacroix” conjures ideas of romantic art like that found in the street market, the upscale gallery is instead focused on contemporary, modern art that minimalizes the usage of obviously traditional props and details that are so integral to the authenticity of Orientalist painters and remain popular with native artists like Chaara. In Tanger: rencontre des cultures artists were chosen for the abstract quality of their work, which Chhibi described as explicitly “non-Orientalist” and “non-decorative.” Chhibi frequently emphasized that “there are conditions and assertions in art” and in the Galerie Delacroix’s exhibits, where only established painters with impressive curriculum vitae are given a space for showcase. Though all the artists save one French woman were of North African origin, most studied at art academies in Europe. The rencontres, or encounters, then, of which the exhibit title speaks, are artistic encounters of space and color, calligraphic lines and rough shapes of people and places representing culture in its most abstract, imaginative form. Visually stimulating, the paintings are showcased in a clean, modern facility that exudes class and modern design with only the most subtle tributes to North African and Islamic architectural styles in the building’s windows and door frames.

Outside and interior of the Galerie Delacroix in Tangier, Morocco

The use of a signature name such as Delacroix to brand a modern art gallery is an attention-grabbing contradiction that appears to have some working success, attracting a steady stream of local and international visitors. Despite this, though the high-art appeal of the Galerie Delacroix, Chhibi says, is lost on many of his Moroccan patrons. “People who come in here see the paintings but start laughing, they think they are a waste of time because they see no bodies, no figures, they think art is worth nothing.” [35] Chhibi hopes that his gallery’s installations will help cure Moroccans of the “artistic illiteracy” from which he believe the majority of his patrons suffer, and help them appreciate the modern depictions of Moroccan culture on display in the Galerie Delacroix. Chhibi holds Delacroix and other European travelers in high esteem for putting Morocco on the map and falling in love with his “international, universal city” of Tangier. Yet like the Galerie selection committee, he is interested in exhibiting new and contemporary visions of North African culture that challenge the viewer to look beyond traditional depictions to picture Morocco in an abstract but culturally relevant and poignant form. “Painting doesn’t have to treat native subjects to be Moroccan!” Chhibi states insistently, pointing to the use of color in many of the pieces.

Look at the style, the colors; they use red, blue, and yellow—colors very typical to Moroccan aspects. The red in Marrakesh is very famous, the Moroccan flag is red. The colors of blue, the pure color of the Mediterranean, white, the color of the sun, beaches, mosques, jellabas, the color of mourning. Yellow, the sand of heaven, land in Morocco is fertile. Green, the flag—this is a kind of identity, a landscape, a plenty, virginity, naturally, originality of Morocco. [36]

The Galerie Delacroix,

Chhibi explains, is constantly engaged in a search for art that is very

contemporary, an art to represent culture and patrimony to foreign and

local

guests. Chhibi’s version of authenticity

differs from many of his countrymen and tourists both for his position

as a

gallery technician who extensively studies art watches art movements in

Morocco. However the most distinguishing feature of his opinion is his

belief

that recognition of patrimony and culture is integral to any piece of

artwork.

“If you forget your identity, you forget your family,” Chhibi repeats,

citing

the example of modern Moroccan artists who, in his opinion, who push

the

artistic envelope for aesthetic creativity and abstract expression at

the

expense of their culture, origins, and identity. Though the goals and

intentions of these artists may or may not be to showcase authentic

representations of Moroccan culture, to Chhibi, forgetting where one

took his

“first steps” demonstrates a lack of respect for one’s identity and

thus,

family and country. Thus, the artists who

integrate modern technique with their Moroccan identity are most

capable of

showcasing Moroccan culture. Moroccan culture, Chhibi says, is very

dependent

on French culture for the means and techniques of creating art that

reflects

culture and society. By integrating parts of Moroccan identity—an

Amazigh

(more

derogatively known as Berber) tattoo as a signature, or abstract

calligraphy in

a modern canvas, artists modernize along with their country, produce a

real and

valuable interpretation of Moroccan culture via art that is every bit

as powerful

and authentic as recognizably “Moroccan” market or family

scenes.

Chhibi’s concept of authenticity is complex, and although the belief that work can be Moroccan and abstract certainly holds true, most visitors come to Morocco with pre-conceived notions and expectations. Similarly, Moroccan audiences and artists, especially those working in the tourism industry, appear to be interested in preserving and showcasing traditional art à la Delacroix then modern, abstract depictions of North African culture. The idea of buying a traditional representation of Moroccan culture while in Morocco is hardly unheard of. This pattern is common all over the world, with tourists buying miniature Eiffel Towers and Moulin Rough posters in France or Petra mugs, rugs, and key chains in Jordan. That a visitor to Morocco should want to buy a painting reminiscent of their Sahara excursion or stay at an opulent traditional hotel fits right in to the commercial schema where countries and cultures capitalize on their exotic factors for memorabilia purchases. Chaara has hit the nail on the head: tourists do not travel halfway around the world for cowboys; they come in search of camels and a different culture and set of experiences from their own.

Why, then, are tourists faulted for enjoying traditional art and experiences? Ibn Warraq recounts an entry he saw in the guest book at the Dahesh Museum in New York City. In the entry, a tourist describes how much she enjoyed the museum’s Orientalist paintings, however, her enthusiastic comments end with an almost guilty note where the she admits that the paintings she enjoyed, being Orientalist in nature, are of course imperialist and reprehensible works of art. [37] Warraq believes the tourist’s self-imposed guilt for enjoying Orientalist art is undeserved. “How many,” Warraq asks, “other ordinary lovers of paintings, sculpture, drawings, watercolors, and engravings have had their natural inclination to enjoy works of Orientalist art damaged or even destroyed by the influence of Edward Said and his followers?” [38]

Warraq’s criticism of the tourists’ guilt raises very important questions about the consumption of art by audiences around the world. Although the work of anti-Orientalists such as Said, and post-modern artists presents an important critical perspective of the legitimacy and effect of Orientalist art on North African and European consumers, the popularity and public interest in traditional interpretations of North African art and culture stems from a variety of interests and intentions.

The relationship between enjoying traditional depictions of Morocco and Orientalist ideologies make any discussion of authenticity and the viewer’s intention complicated by their culture or native perspective. Certainly, persons from different backgrounds enjoy and interpret art differently. But where Mohammed Chaara felt free to acknowledge and admire Delacroix for his paintings, the tourist at the Dahesh Museum did not allow herself to enjoy the Orientalist art work without acknowledging its history. Perhaps, outsiders may or may not be able to fully grasp or understand the full cultural implications and messages of North African art in the same way a Moroccan viewer would, but this fact does not make their judgments and opinions inherently flawed. As notions of authenticity evolve with different artists, art movements, and popular culture and expectations, the differing implications for Moroccans and Europeans enjoying and/or producing images of North Africa are subjects for additional analysis along with the greater thematic question of what constitutes an authentic representation of North African cultures.

Many artists are loath to categorize themselves or their work, but for Mohammed Chaara, describing his identity as a Moroccan painter is simple. “I am a mix of Morocco,” Chaara says. “I am not a regionalist, I am universal.” [39] Chaara’s self-proclaimed universality speaks volumes of the complexity of depicting a culture authentically. In 1832, a European painter creates images of Morocco from firsthand observations; nearly two centuries later, a Moroccan artist references the European’s work as a source of artistic inspiration to paint his country. The discussion of authenticity begins to move beyond what works are Orientalist or anti-Orientalist, showing the complexity of the issue of authentically representing a culture subject to multiple interpretations and fantasies. As history, imagination, and memory entwine, Moroccan culture becomes defined in both European and Moroccan images and styles. But can one determine which style, if any, is an authentic representation of North Africa?

The definition of constitutes an authentic representation of any culture, be it in art, film, or literature, is complicated by the question of whose opinion dictates what is authentic and what is not. Lisa Suhair Majaj discusses the lack of consensus among the Arab-American population about what constitutes an Arab-American identity as a roadblock in determining what constitutes a genre of Arab-American literature. “Who should be charged with the authority to make these distinctions?” Majaj inquires. Though writers, she says, “are of course affected by, and write out of, their identity and experience,” she advises against passing judgment on Arab-American literature on the basis of content because “writers are not simply spokespeople for their communities; they are artists.” [40] Majaj believes that the genre of Arab-American literature, like Arab-American identity, is still in the process of being created. For her, the art that results is Arab-American “because it arises from the experience of Arab-Americans — personal or public, ‘ethnic’ or not.” [41]

Majaj’s inclination to reject authenticity as a criterion for judging or appreciating art is notable for its forgoing preconceived notions of culture and identity and instead focuses on enjoying art for art’s sake. However, authenticity plays an important role in the judgment and appreciation of art, and frequently the more “authentic” an art work or experience appears, the more valuable and meaningful it becomes to the producer to make and consumer to enjoy. The notion of authenticity played and continues to play an important role in the choices and tastes of artists and patrons from Delacroix to today.

Authenticity is defined by what the visitor wants to see, but it is also comprised of customs and images the native population wishes to have representing them. Delacroix’s Algerian harem visit was the result of multiple inquiries on the part of the artist who desired to see an authentic Moorish home, but the household in turn prepared for his visit with women dressing in their finest clothes, setting out an ornamented traditional spectacle. Delacroix’s experiences, preserved for the ages in large oil paintings, then became a standard for authentic depictions of North Africa because the images were painted from the artists’ own experience as well as aesthetically valued for the detailed work.

Since then, the work of Delacroix and other Orientalist artists been used by many artists of European and North African descent. These traditional images were a point of reference and a point of departure — a standard of authentic North African content as well as aesthetic, artistic detail. Henri Matisse’s paintings were a study of Moroccan light and colors, not people and place. Standing in stark contrast is the work of Houria Niati, whose No to torture confronts the stereotypes she believes to be misleading and abusive of the women subjects of the painting, reclaiming them and their identity as North African.

Engaging with Orientalist depictions of North African culture is integral to a cross-cultural study of Western art depicting the Arab world. Though a majority of tourists and Moroccans prefer traditional depictions of North African culture, there is a burgeoning field of modern artists, both internationally recognized and locally celebrated, expressing a variety of messages and themes about North African culture that are every bit as powerful, if only visible to select and self-selecting audiences.

The Miroirs d’Orients exhibit in Lille is an encouraging development, and provides visitors with the opportunity to learn and react to the exhibit beyond the exhibition space. A final portion of the exhibit invites viewers, now acquainted with Orientalism, to search the rest of the Lille Palais des Beaux-arts for other Orientalist art and interpret those pieces in the collection with their new knowledge. By actively engaging the viewer with the history of Orientalist painting and its consequences on contemporary perceptions of Arab cultures, viewers are given the opportunity to gauge the value of different art works from an informed perspective.

The museum also offered a child’s guide to Miroirs d’Orients that encourages youngsters to think critically alongside their parents or patron. The nineteen-page pamphlet explains the same history in simpler terms and provides younger museum guests with a variety of exhibit-related games and activities that teach children how to distinguish between stereotypes and the importance of doing so in basic terms. Like Majaj’s discussion of Arab-American literature, which struggles to define the genre by author ancestry versus subject matter, the debate over whether content or aesthetic style and a painting’s detail make it an accurate representation of North African culture is difficult to determine.