Ben Guthrie (2009, UW ID) is an Equipment Designer at The North Face. Prior to joining The North Face, Ben worked as an Industrial Designer at the design consultancies Smart Design and Fathom, as well as the the manufacturer Plastikon Industries. He has also designed bags and hats for Levi Strauss & Co. Ben’s work has been featured on Yanko Design, and has been recognized by the IDSA. The North Face is an American outdoor clothing and equipment manufacturer headquartered on Alameda, an island just east of San Francisco and south of Oakland. The company’s name is based on the fact that the north face of a mountain in the northern hemisphere is generally the most challenging route to climb, due to cold and ice.

Never Stop Exploring

The North Face

Ben Guthrie

Nov 10 2015

Part One

Preparation and Networking

You’ve worked at two well-known design consultancies—Smart Design and Fathom—as well as at two corporations—Levi’s and the North Face. What were some of the strategies you used to look for work after graduation?

When I graduated in 2009, it was not the best timing. It was the height of the recession, so there was fierce competition for only a few opportunities. Eventually I pushed through and made it, but it was kind of rough for a little while.

I put a lot of work into my portfolio. Preparing your portfolio is such a daunting, never-ending task. I tried to make sure that each project in my portfolio had a focus—for example, highlighting a particular skill, or showing well-rounded ability overall. I also tried to make each project into a story, because it’s a lot more captivating to present your portfolio that way.

Besides the portfolio, I also made a resume and a little teaser—a kind of mini portfolio. I actually think that teaser was super important, because it was the first thing that most people looked at. Of course, I had a website as well.

I put a lot of work into my portfolio. Preparing your portfolio is such a daunting, never-ending task.

Once I had my portfolio, resume and teaser together, I just got out there and started networking and meeting with people. I utilized all my resources—I reached out to all the UW Design professors as well as all the other designers I knew. I asked each person to meet me for coffee and give me advice on my portfolio. It’s great to practice running through your portfolio presentation as much as you can—I got a lot of feedback that I used to improve it.

For example, when I showed my portfolio to a designer in San Francisco, she said, “You show that you are really good at problem solving, but what’s missing is a project that shows loose, more expressive thinking.” After that, I took a weekend to do a more conceptual, light-themed design project that I added to my portfolio.

It’s super helpful when people identify parts of your portfolio that are neglected—if you are missing a skill, or if there’s an area that you aren’t representing well. But more importantly, by meeting with people one-on-one you’re creating relationships, building your network and becoming part of the design community.

The best way to find jobs was networking.

How did you find out about specific firms and job opportunities in the Bay area?

I did all sorts of things. First, I looked at job boards like Coroflot—Coroflot has postings from all over the world. I also went to individual company websites and looked at their job pages. But in the end, the best way to find jobs was networking. For pretty much all the jobs that I’ve had, I only found out about them by talking to people. For example, when I first moved to San Francisco, I would go to all of the IDSA events— that’s how I met the designer who later was my boss at Smart Design.

Was it difficult to ask people directly about becoming a designer at their company?

I tried to be pretty casual and low key, not pressing at all. Allan [my boss at Smart Design] was at an IDSA event I went to. He told me, “You know, we offer internships regularly. Every three to six months we have a new intern.” He gave me his card and recommended that I send him my work, my resume and my teaser. So I did that. He must have looked at it, because he emailed me back, saying, “Great work!” When I got that email I was so excited—he enjoyed my work, which was amazing.

I also followed up with another industrial designer at Smart Design in SF—an UW ID alum, Shannon Fong. A contact back in Seattle had recommended that I get in touch with her. I connected to her through LinkedIn, which was a total shot in the dark—but she ended up being great. She was very receptive when we met for coffee, and she gave me a lot of feedback on my portfolio. Thanks to her and Allen, I was invited to interview at Smart for their next internship.

It was actually a pretty low-key interview because I had already met Shannon and Allen. There were a couple of other designers besides the two of them. At the interview, I projected my portfolio PDF from my laptop. I also brought a small physical model that I’d made, and I passed that around. Everyone at Smart was super nice—they have a great work culture, very laid back and casual.

I followed up afterwards with a special thank you note—I drew a funny illustration just for them. At Smart Design, one of their best known products is the OXO potato peeler—you know, the one with the fins on the handle. So I made this cute little drawing of a group of potatoes with eyes. The potatoes are looking at the OXO peeler sitting next them, totally freaked out.

Part Two

Finding Your Fit

What was it like working at Smart Design?

They have a great culture. I learned a lot at Smart. One of the big things I took away from them is the importance of the human element—they are really good at “designing for people.” It’s such an important message for all designers. It’s all about empathy, understanding your user, and improving their experiences.

Working at Smart Design

"I helped design a silicone drying mat for OXO. I still remember seeing it at Target—I think every designer remembers that moment—their first product in the store. I freaked out when I saw it on the shelf. I took all these pictures with it. I’m sure I weirded out all the other people in the store. Anyway, it was really cool, being part of the project and the design process."

Freelancing forced me to step up and learn how to present my ideas with confidence.

What did you do after your Smart Design internship?

I started doing some freelance work. Some of my friends were involved in a start-up, and I did their branding and identity materials. I also did some work for a company called Travel Chair—they make fold-up camping chairs, and they were looking for someone to produce some fresh concepts. Designing those camping chairs turned out to be really fun. It was a cool project.

Because I was completely on my own, I think this freelancing period really helped me grow as a designer. I didn’t have professors or managers in between me and the client. I didn’t have anyone to ask, “Hey, is this a good idea? Should I show this? What do you think of this?” Freelancing forced me to step up and learn how to present my ideas with confidence—to have my own point of view. That was really good for me.

I also started becoming more involved in the IDSA San Francisco chapter. I volunteered to do the graphic design for different events, and to generally help out on several projects. Being involved in the IDSA helped me meet all kinds of creative people. It grew my network, and as a result, I heard about many more employment opportunities. I interviewed at several places, and actually got to a point where I had to choose between two different job offers.

One offer was for a full-time, staff design position at a company called Plastikon—a custom plastics manufacturer. The other offer was a contract design role at a prestigious design consultancy. I wasn’t sure what to do—there were pros and cons on each side. I actually still think about this sometimes—what would have happened if I had taken the other job? I ended up going with the full-time offer at Plastikon because the economy was still fairly unstable and I was applying for a new apartment in SF, but I also was really interested in learning more about engineering and the technical side of product development.

What kind of work did you do at Plastikon?

Plastikon does custom plastics manufacturing for automotive clients like Toyota and Tesla. I was hired to work for Plastikon Pro, a smaller in-house design development lab. At Plastikon Pro, I was involved in a lot of brainstorms. I was the “go-to sketch guy”—people would have ideas, and I would sketch them out quickly on a dry erase board.

In these brainstorms, it was mostly me and a bunch of engineers, so I learned a ton about engineering and manufacturing—all about materials and their properties. I learned how to design a part to be made efficiently, considering factors like flow and shrinkage. That was really cool; I got a lot of great experience in engineering. I was also working in Solidworks quite a bit—that’s a great program to learn.

But after a year or so, my boss at Plastikon Pro left the company, and he brought me and a few other people with him to create a start-up that eventually became Fathom.

How was your experience at Fathom?

In the beginning, I had to wear many different hats. I was the lead product designer, but I was also the branding/VCD person. It was hard just coming up with the name “Fathom”—and even after we had the name, creating the entire visual identity was so much work. I was really busy with that for a while.

Eventually I started working more on product design, which was cool because that’s what I really wanted to do. We did quite a bit of work for a company called Calibowl—the product itself, as well as the visual branding and packaging.

A really cool thing about Fathom was all the awesome prototyping resources. Besides a full woodshop and spray booth, we had seven different 3D printers that could print more than fifty different materials. We even had this desktop injection molding press where we could 3D print a tool, and then do injection mold prototypes for short-run, low volume testing of actual plastics. It was super cool to be a part of Fathom, and to have all those resources at our disposal. I think now they even have SLS machines and casting—just a plethora of prototyping resources.

Designed by Fathom: Calibowl

"Calibowl is a line of non-spill bowls. They are really awesome. The inside lip of the bowl curls back inside, so nothing spills out—anything that goes up just falls back into the bowl."

Part Three

A Day at the North Face

How did you break into the outdoor product industry?

I started by following all kinds of blogs that are devoted to outdoor gear, especially bags. There’s a great blog called Carryology—they interview designers in the industry, and write critical reviews of new products. I emailed the authors there, and asked how I could learn how to design soft goods. When they wrote back, they said there was really no specific school or resources to learn how to design bags. Essentially, their response was, “You just have to get in the industry somehow. Once you’re in, you’ll learn on the job.” That was disappointing—I was really hoping for some book they could recommend or something.

So I just tried to immerse myself fully in the world of soft goods. I bought a sewing machine, and a copy of “Sewing for Dummies.” I started sketching sleeping bags and other cut and sew type products. I started to think about patterning, and how to design products with efficient cut yields—zero waste. I started designing backpacks, thinking about access points and different types of closures—how backpacks could be more versatile, expandable, or even modular. I experimented with shapes that might carry your stuff better, or shapes that could wrap around the user. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I just started sketching ideas out, and I put them in my portfolio.

Did all of that work pay off—did it help you get your job at The North Face?

Yes. One day, early in the morning—totally out of the blue—I got an email message through my online Coroflot portfolio. It said, “Hey Ben, let me know if you’re interested in a full-time equipment design contract role at The North Face.”

I couldn’t believe it. I read the message a bunch of times—I thought it was spam at first. But there was an email address to reply back to, so I responded and it was legit. The guy who wrote me is actually now my current boss at the North Face. So anyway, a few days after I responded, I went in for an interview.

But I didn’t get the position. They were very honest and upfront with me. They said, “It looks like you have some really great skills, and you have good design thinking. But we’re a little worried about the amount of experience you have in soft goods. We’re interviewing you and someone else who has more experience than you—then we’re going to decide.”

So unfortunately, I didn’t get it. They went with the other guy. But it was okay—we had a great conversation, and I got a lot of good feedback on the projects I presented—they had specific suggestions on how I could make them better. And they suggested that I stay in touch with them.

So I took that feedback and went back and improved my portfolio. I also added more projects. Then, six or seven months later, I reached back out to him, and as it happens, they were again looking to fill another contract position. So I went and interviewed again, and this time I got it. I was so stoked—this was it—I was in! My goal happened! I got into the industry! I broke in! Even though it was just a contract, I thought, “Yes, I made it!”

What was it like working at The North Face?

At the start, I had a seven-month contract in Equipment. I was supposed to be focusing on bags, mostly backpacks. But my first project was actually a series of stuff sacks.

The North Face had found out that most of their sleeping bags and tents were not being fully setup in retail (i.e., at REI) because there wasn’t enough floor space. So customers couldn’t see the actual products—everything was sitting on shelves inside these one-color, bare-bones style stuff sacks. Some of the sacks had a small model name printed on them—it would say “Dolomite 2S” or something obscure like that. Sometimes customers wouldn’t even know if the content of a sack was a sleeping bag or not.

My First Project at The North Face

“I changed the shape of the sack to have a triangular profile, so it stacked in a more interesting way. I also redesigned the graphics to show a little image of the product inside, as well as a list of product features—the temperature rating, etc. The hardest part was the cost constraint: eighty cents. So we used the scrap fabrics left over from the product to build a handle, and we added little material swatches so customers could see the colors and feel the fabric. It was actually a cool story about using waste.”

After that, most of my time was spent designing backpacks, especially daypacks. I worked on everything from back-to-school daypacks to super-modern, progressive, urban, professional-type packs, to the vintage-inspired, heritage, retro pieces that were trendy for a while.

Eventually I got into technical packs, which I think are the most fun because they’re the more outdoor-activity based. There are designs that are specific to hiking or climbing, and they’re all about being faster and lighter—very performance driven.

A really cool thing about working on technical products is that we get to work with the athletes. We have a huge team of TNF sponsored athletes—professional climbers, runners, mountaineers, skiers and snowboarders. We give them our newest prototypes, and ask them to test it on their next expedition. Sometimes they bring it back, and it’s all shredded up and they say, “This thing sucks!” But usually, they say, “This thing’s pretty cool! But it would be better if it held this tool in this way, or if this part was a little different.” That part of the process is really awesome. I think it adds a lot of credibility to the product and to the brand in general.

Have you worked on other products besides backpacks?

This is still within Equipment, but I did want to bring some of my prior hard goods experience to the table and show people at The North Face what I was capable of making. So I started sketching and modeling out custom hard goods—trims that go on the bags like zipper pulls, buckles, cord locks, whatever. These actually got developed—one of my zipper pulls was put on a couple of packs. The next season that zipper pull was adopted by a bunch of the apparel departments and put on all kinds of jackets. It was very inspiring to see it spread across the entire North Face brand.

I did work on apparel in Snow Sports. After about a year and a half in Equipment, a new six-month contract position in Snow Sports opened up, and I applied for that and got it.

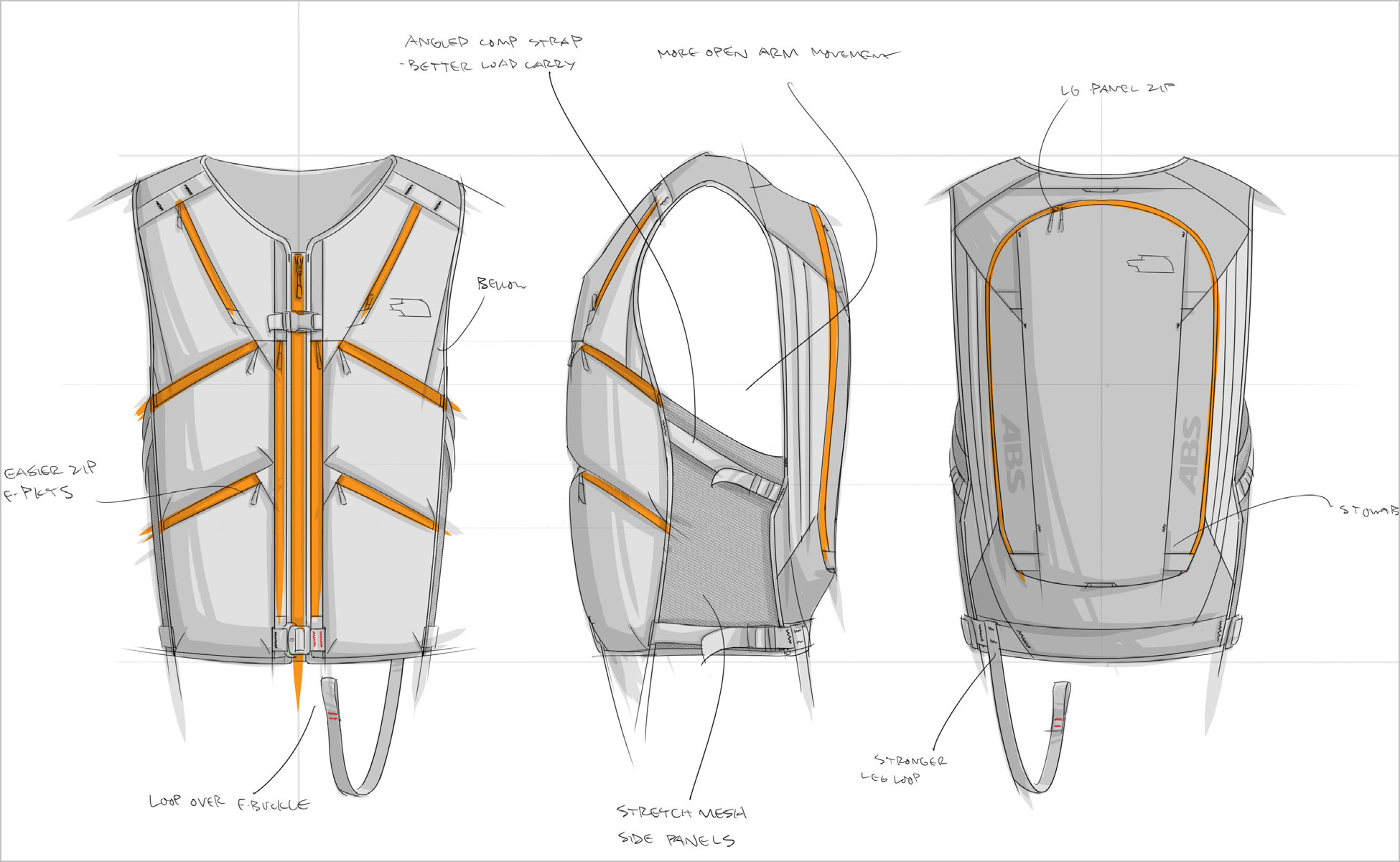

In Snow Sports I worked on jackets and bibs for ski patrols and mountain guides. But my main project was designing a new ABS safety vest for backcountry skiing and snowboarding. If you get caught in an avalanche, you can pull a little trigger on the vest. Airbags inside the vest inflate and help you float to the top of the avalanche so you don’t get buried alive. It’s been really successful at saving people’s lives. It was an awesome project to be a part of.

The North Face ABS Safety Vest

Ben Guthrie’s sketches for a life-saving ABS safety vest for backcountry skiing and snowboarding. The vest contains inflatable airbags that can be triggered by during a snow avalanche, helping users float to the top.

It was a really good project for me, because it was a hybrid of equipment and apparel. It’s still a garment that you need to wear; it needs to fit. But the vest also has all these requirements for carrying gear. The front needs to have pockets for quick, on-the-go access—to get your ski skins and goggles, for example. The back of the vest needs to hold other gear, like a snow shovel, a probe, your skis or a snowboard—while also containing the entire airbag system. We also had to think about sectioning for movement—when people of different heights are wearing the vest, they’ll still want to move around, or get on a snowmobile.

There were so many different factors involved that the design development was pretty intense. Even after we had the design figured out, getting everything dialed down was very complicated and difficult.

For example, just the airbag system on its own is insane. The canister has to be tucked out of the way, but still easily accessible for initial installation or replacement. The hoses from the canister need to be routed safely to the airbags. The airbag pockets have to be constructed with a lot of strength, so they don’t blow out when the airbag inflates. These pockets also have to be shaped to direct the inflating airbag into a specific port. The port itself needs to open with just the right amount of force, but that same port should also stay securely shut at all other times.

To top it all off, just the fact that this was a lifesaving device upped the ante. It was a bit overwhelming. But in the end, it was so gratifying to get everything working just right. I’m really proud to have been a part of this project.

Can you describe your typical working day?

Well, my schedule in the mornings is driven by the ferry. I live in San Francisco and ride my bike to the ferry. The North Face campus is in Alameda, right across the bay and right next to the ferry dock. So I am usually at work by 8:15 or 8:30am. I’m typically there until 6pm, unless it’s an especially busy time. I rarely work on the weekends, but there are crunch times when I might stay late—maybe to 8 or 9pm.

My work really depends on where we are in the product cycle. All our products are split into two seasons: Fall and Spring. We work about two years in advance. For example, right now I’m working on products for Spring and Fall 2017. The first year is the actual design time—all the initial research, concepting and design crits. The second year is development and prepping for production. Design is hands-off during the second year—it’s more on the developers, who are basically the engineers of soft goods.

We work about two years in advance… At the beginning of a season… [we] will figure out what new products we should design for the next season.

Typically, at the beginning of a season, the product managers and the product director on my team [Equipment] will figure out what new products we should design for the next season. For example, they’ll want to redesign a few of our commuting daypacks, or they’ll want to add new packs for traveling. The product folks are merchants—they study the markets and manage the product line. They write initial briefs that the entire Equipment Team will discuss back and forth for a few weeks. Then, we have a big kick-off called the “Hoe-Down.”

After the Hoe-Down, at the beginning of the design process, we have a lot of brainstorm meetings across departments. We really like to meet with designers from footwear and apparel. They’ll often have a direction that they are excited about. Their ideas might inspire us to do something new or change our own direction a bit.

In the middle of the design process, we usually make two or three trips out to our factories in Vietnam. The designers and developers work in-person with the factories to refine and dial in the product in the sample room, before it’s put into line production. During the first development trip, you can be looser and explore lots of different things. At the end of the second trip, you need to be refining. The product should be as close to done as possible—we don’t want to make many changes afterwards.

What do you like most about working at the North Face?

There are so many things. I think the biggest thing is just the group of people I get to work with—it’s a really great culture. It’s so fun working with them that it doesn’t even really feel like work. The North Face is a total family, at least on the Equipment Team. There’s always activities that we’re doing right after work or on the weekends. Sometimes we’ll spontaneously plan a camping/product testing trip. If we’re lucky we get to do these trips during the week—just locally, up to the Sierras or out to the coast. Testing the product out in this way is just great.

Part Four

Love Your Craft

It may sound obvious, but getting the standard hard skills down is very important.

When you look back at your time at UW, what do you think was the most valuable part of your education?

It may sound obvious, but getting the standard hard skills down is very important. Sketching really loose and fast, just being able to get your ideas out to communicate to others. Learning industry standard tools—Rhino, Illustrator and Photoshop.

The more I grow in my career, the more I appreciate that I was able to learn the design process in school. Especially focusing on the early phases of research, when you can discover real insights and the opportunities. Those are the things that should drive the design. It’s too easy to just jump into sketching and start trying to come up with ideas without really understanding the user.

Also, critiques. You might be able to learn software by yourself, but you really can’t learn how to give and take feedback on your own. Critiquing is such an essential part of the design process for any design team. At The North Face, I still do crits all the time. I remember when I was first introduced to critiquing in the program—I was super nervous. It’s so hard to get up there, show your stuff on the wall, and then take criticism. It took awhile, but eventually I got comfortable, and really started opening up and even soliciting feedback. Getting feedback to improve my work was great, but also just being more comfortable in the process made me a better collaborator overall.

Fun and Games at The North Face

A portrait of Ben Guthrie, in a self-designed costume for the North Face Halloween competition.

Do you have any advice for UW Design Students?

Find the time and make the effort to do extra stuff outside of the curriculum and the classwork that you’re already doing. Enter design competitions—it’s extremely helpful if you can get some honors and put that on your resume. Go to portfolio reviews. Be part of the local design community—that’s how you meet people and learn more about the professional design scene outside of school. This can lead to interviews and internships. It always helps if you meet someone in person—as opposed to emailing a stranger, that’s just a shot in the dark.

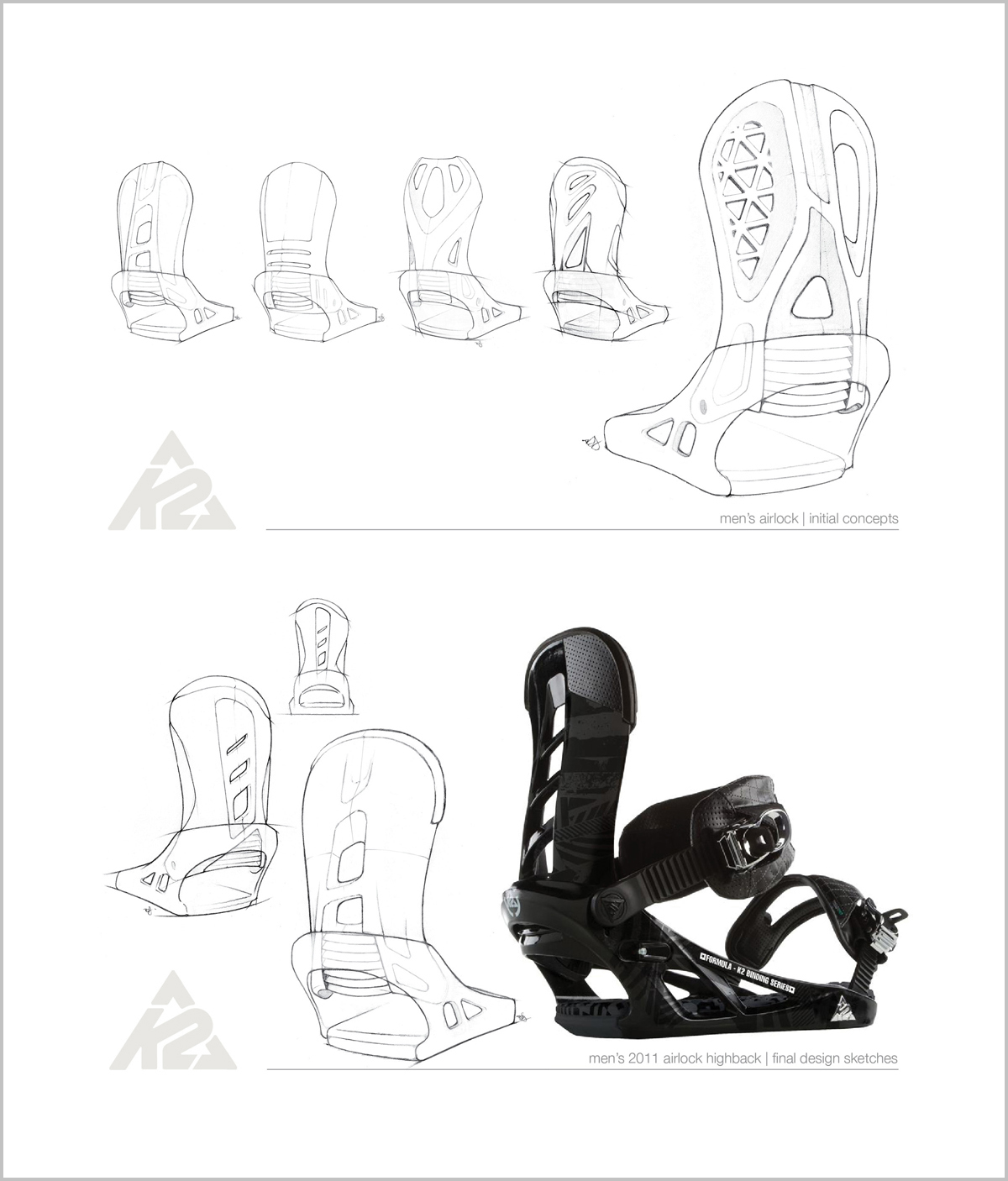

Get an internship while you’re still in school. I had a really great internship in the summer between my junior and senior year—I worked at Built Design in Everett. We designed snowboard bindings for local outdoor companies like K2 and Ride. It was really cool to be a part of that process, and at the end, I had good projects that I could add to my portfolio.

The more you know about the other disciplines and everything involved in a product, the better you’ll be equipped to design in the future.

Learn how to communicate and correspond with other designers. You want to connect honestly with people, without being too formal. Some emails are way too long—people are busy, make sure you are short and concise. But be real. Show your true personality. That’s always interesting.

Stay driven, and stay curious. Try to learn more about other design disciplines—interaction design, graphic design, design research, design strategy—learn more about their processes and how they do things. The more you know about the other disciplines and everything involved in a product, the better you’ll be equipped to design in the future. Curiosity is what drives innovation.