NASA JPL (Jet Propulsion Lab) is a federally funded research and development center located in La Cañada Flintridge and Pasadena, California. JPL focuses on robotics, planetary exploration missions, Deep Space Network coordination, Near-Earth Objects Program development, and earth science missions; their recently launched missions include the Mars Curiosity rover, Juno, and Jason 3. Erin Murphy received her BA from the UW Interaction Design program in 2013. Erin previously interned at TEAGUE, a design consultancy agency specializing in product, information design, and user experience solutions. She was also an intern at Boeing, where she redesigned touch interface experiences for flight decks before working at NASA JPL.

Design, Space and Curiosity

NASA JPL

Erin Murphy

May 10 2017

Part One

Applying Interaction Design in Space

Why did you choose to work at NASA JPL?

I think the appeal was that I had no idea that applying something like interaction design was actually possible at NASA. It’s a very engineering and science-centric facility, so I wasn’t sure what it meant to be a designer there.

It also seemed like a place where I’d feel like an outsider. When I was interning at Boeing and enjoying the research I was doing with flight decks, Axel Roesler (Assoc. Professor of Interaction Design) suggested that NASA JPL might be a compelling field to jump into. I said, “Yeah, ok. I’ll go ahead and do the NASA route for a little while and see how I like it.”

At that time, I recognized that I needed to try something drastically different and see if I could be happy in an environment that was not exclusively occupied by other designers. That’s what motivated me to come to JPL.

Also, space is just fascinating! I did a collaborative senior project, Pollux, that was about stargazing and making amateur astronomer tools more accessible and user-friendly. It’s hard to admit now, but prior to my senior project, I was not very interested in space. I just didn’t see how I could be a part of that type of exploration.

But the more I researched the amateur astronomer community, the more aware I became of the problems with available tools for observing the night sky, and I started to see how interaction design could help people by offering alternative methods of learning about space. That’s how I developed a passion for exploring design interventions in space exploration.

I’ve learned how to be a designer in a space where people were also just learning how to work with a designer.

What were your expectations going into this job?

I don’t think that I had any expectations with this position. I really wasn’t certain what I was getting myself into. If I had gone to a design firm, I would have had expectations on how interaction designers provide value to a team. At a design firm, there would be people that looked at problems in the same way that I did, and understood the importance of good design and clear communication.

Instead, during my first year at JPL, I was really challenged by understanding the technical domains of the people who work in aerospace and planetary exploration. Once I was able to understand these complex systems, the conversations became less esoteric, and it was easier to get to the heart of some of the design problems people were experiencing with their tools. Honestly, I think that Interaction Design is a new field for the scientists and engineers here as well. I’ve learned how to be a designer in a space where people were also just learning how to work with a designer.

A Typical Day at JPL

"Most days I interface directly with engineers and scientists, developing diagrams and storyboards of the various processes that will be used to conduct science on the surface of Mars."

How would you describe a typical day?

Most days I’m interfacing directly with engineers and scientists, developing diagrams and storyboards of the various processes that will be used to conduct science on the surface of Mars. I also find myself facilitating the communication strategies of the Mars 2020 Science teams to other stakeholders and teams on the mission. Some days I act as a visual communication designer, helping other team members break down complex material into a set of graphics that can be more easily understood by other engineers on the mission.

The days that are particularly interesting to me are ones that have what I like to call ‘JPL Moments’—moments when you step back from the design work, reviews and meetings and realize that you’re building spacecraft! Someone might ask me, “Do you want to see this spacecraft that we’re building right now? Do you want to see this cubesat that’s almost done?” I’m like, “Of course!”

How would you describe your role as an Interaction Designer at JPL?

I’m technically a Senior Interaction Designer / Science Systems Engineer for Mars 2020. As an Interaction Designer, I conceptualize user experiences for the future digital tools that geologists and astrobiologists will use when conducting science with the Mars 2020 rover. I facilitate the design and planning of processes that will allow scientists to efficiently plan and execute science activities on Mars 2020, and I think about the future tools that rover planners and scientists will need. My current focus is designing user interfaces for targeting on the surface of Mars, and for safely placing the rover arm on specified terrain targets.

A lot of my work involves sketching out potential user experiences and discussing their feasibility and implementation challenges with our science and engineering teams. I’m often pulled into meetings to help other members of the team sketch out their ideas and processes for the mission—very few people can produce these rapid sketches, and it’s useful to have someone who can help make ideas more concrete.

A lot of my role is just helping people on this mission take abstract plans and ideas and bring them into a tangible concrete form—to facilitate clear communication through visualization.

Currently, the mission is in a heavy planning phase; none of the conceptual mock-ups and storyboards I’ve designed will be put into the process of development for another year. I think that’s what makes this position so interesting. I’m a part of a long-term design process, and because of that, the normal pace of iteration has scaled from hours to months, maybe even years. The longevity of these projects changes the way that you think about producing designs and building software.

As a Science Systems Engineer with Mars 2020, I’m responsible for specific subsystems. I’m working with a geologist who is designing how the future science team for Mars 2020 will define science objectives, routes to interesting outcrops with the rover, and document new discoveries of the ancient geologic history of Mars.

What’s interesting for me is that I get to visualize and plan the procedures scientists will use to operate the rover with storyboards and user workflow diagrams. I’ve learned so much about a field I really knew nothing about prior to JPL, such as basic geology and stratigraphy, and how geologists analyze geological structures on field trips.

One of the main challenges across all missions during this planning phase is consistent communication of a team’s progress. Given the complexity of each element of the spacecraft, clear communication is essential. Often times, the engineers and scientists are forced to just get their ideas out to the team through bulleted lists in giant slide decks. The team recognizes the need for better visualization, but few have that skillset in the same capacity as a trained designer.

I’ve used a diverse set of methods to maintain consistent communication of our future plans. I directed a concept movie depicting what future rover operations will look like with new software; I sketched a series of workflow diagrams with the engineering team to help map how people will review the safety and wellness of the spacecraft with new commands; I create animated gifs depicting the execution of flight software. I feel that a lot of my role is just helping people on this mission take the abstract plans and ideas they have in their heads and bring it into a tangible, sharable, concrete form for conversation.

Do you see yourself staying for the duration of the 2020 mission?

That’s kind of a hard one. There’s always times at JPL where I think, “It’s time for me to leave. I need to go on and do other stuff.” But I get drawn back in by thinking, “Well, you could leave… but there’s a future M2020 mission that is going to conduct some amazing science on Mars—which you could help with…” So that’s the frustratingly wonderful part about it.

As a member of a mission, I get to interact with people that I never thought I’d be able to work with—we have amazing conversations involving spacecraft. When I first arrived here, I didn’t initially feel that I could be a part of this culture to the degree that I am. But once I was imbedded into the process and projects, and experienced how people think through these complex problems, I started to understand where I might have an impact.

Part Two

Staying Inspired

What is your favorite project that you’ve worked on?

Mars 2020 is my favorite. I just love all the rovers that are up on Mars right now. I admire the people who have sent the rovers to Mars—they are so resilient and capable of taking on these kind of problems. I get to see all these people come together and build a rover. I get to focus on multiple potential applications of interaction design in this space, from thinking about how we can design better systems for people to plan execute science, to creating data visualizations of how flight software executes commands on a rover. I like feeling that I’m not just having a small piece.

What is the design validation process like?

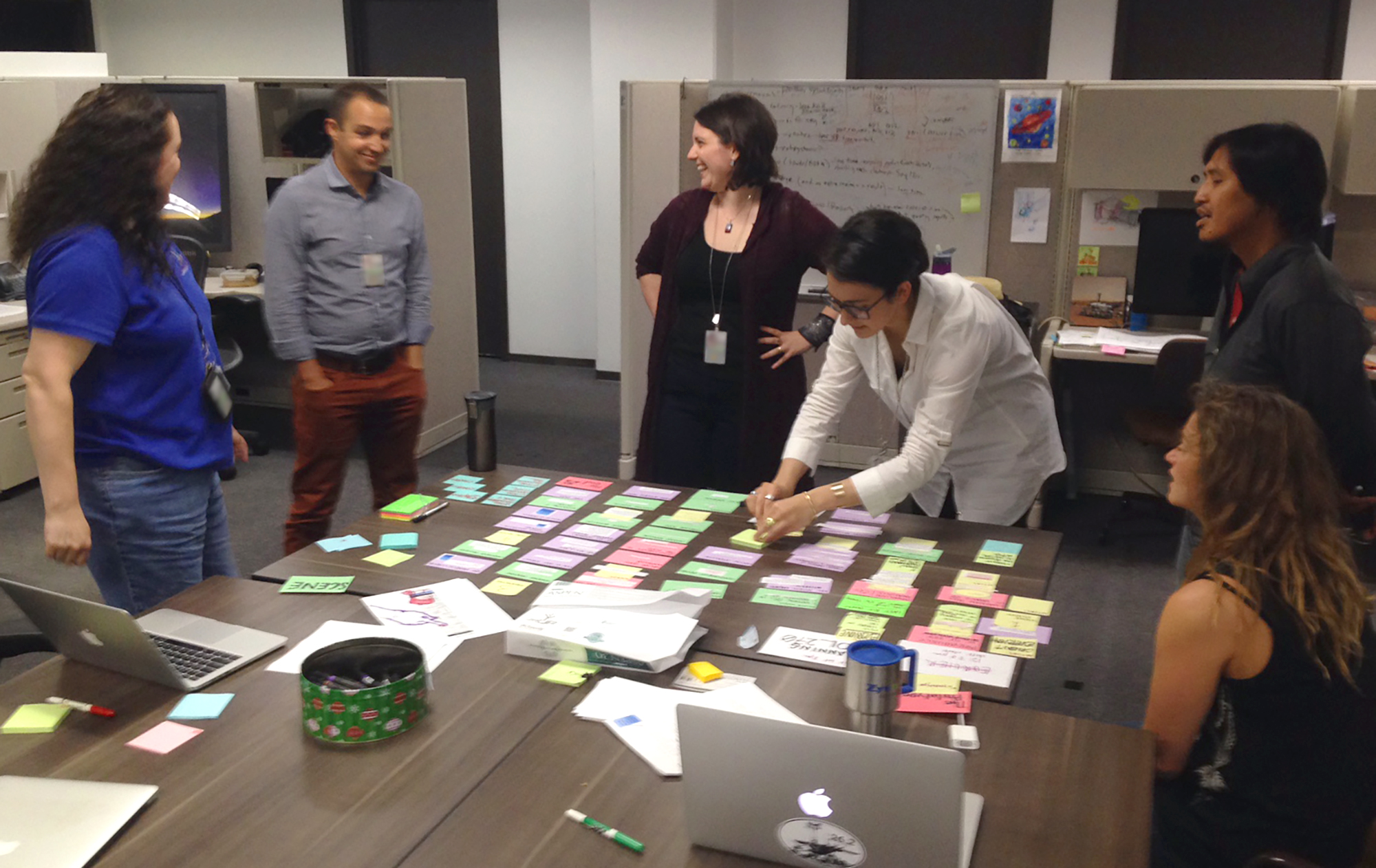

The validation process is interesting. With Mars 2020, I am working on a team that is composed of geologists as well as the mission planners. I’m at the intersection of both of those groups. So a lot of times I’m pulling these separate groups into a room for a design critique on a specific design.

If I’m trying to get feedback from specific stakeholders, I’ve found that I have to facilitate the discussion through sketches and diagrams that I’ve created to help others understand the changes I want to see in the planning of potential science tools and processes.

Something that was interesting when I was working with engineers and scientists is that, for them, design critiques are a new format for soliciting feedback. I felt like I had to be very explicit and open to harsh criticism. Most of the time they wanted to be polite and were hesitant to communicate their honest opinions on the designs I was creating. I had to be up front and remind them that being brutally honest improves the design.

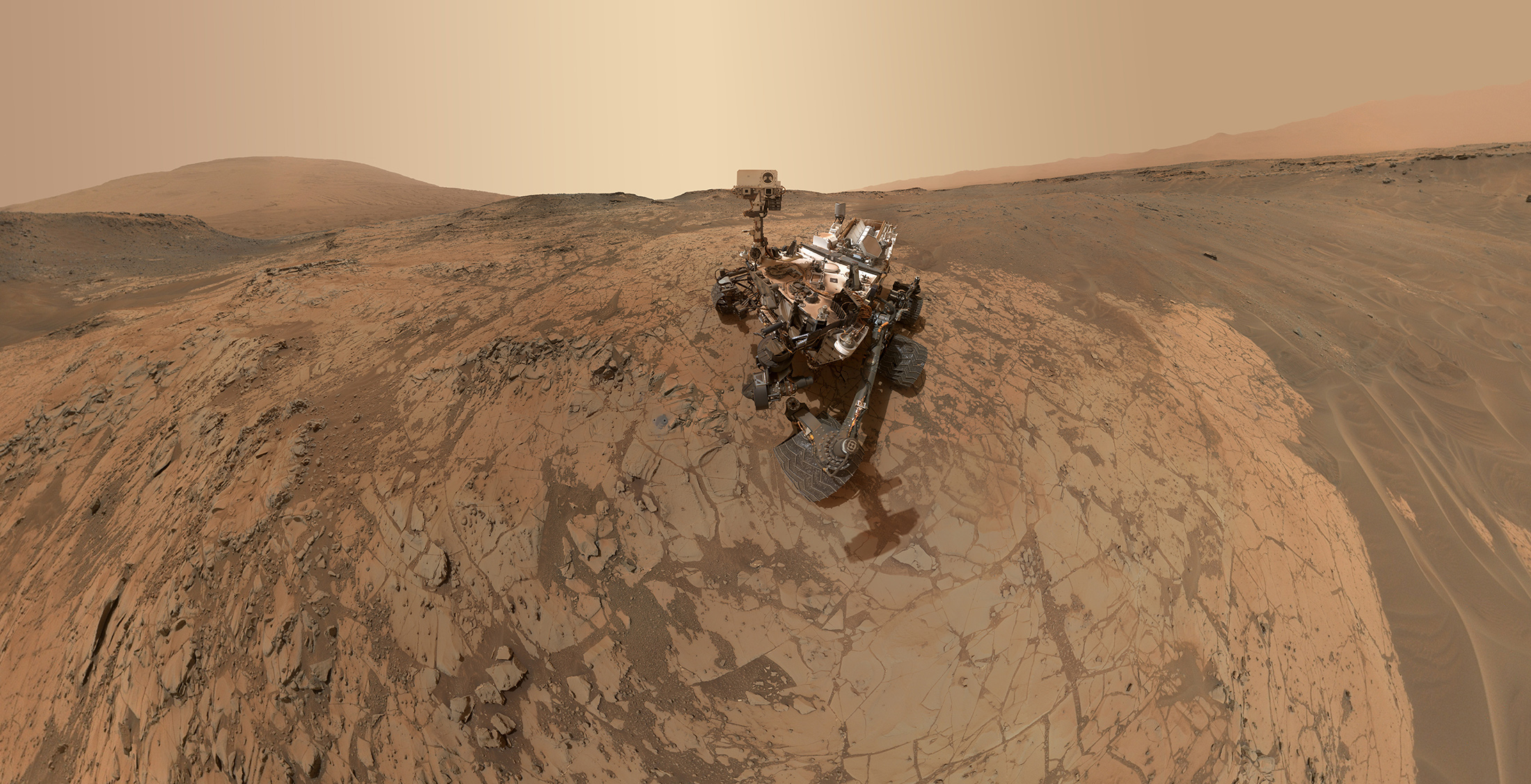

Testbed Curiosity Rover

Engineers and planners use the this full-scale rover in the JPL "Mars Yard” to conduct simulations of complex experiments. After successful testing, commands can be radiated to the real Curiosity rover on Mars.

The roles I’ve had at JPL have been vastly different, thus keeping my interest.

How do you stay inspired as a designer?

JPL feels like the Wild West when it comes to the kinds of roles offered: you have a lot of freedom to move around and see what it is that you like to do.

When I first started, I wasn’t doing anything that to the same level of the interactions that I have with these mission planners on Mars 2020 today. I wouldn’t have been able to have those conversations then—it took me a long time to understand how we plan and execute science activities on Mars using rovers and relay communications.

So I stuck to the things I was comfortable with, which was doing the design work: conducting interviews with users, doing the interfaces, doing the final visual design of those UIs. I was certain that building tools through the user experience and supplemental UI design would be my role at JPL.

But I also noticed that mission planners have this really challenging process of creating the processes for missions in the future, and their findings are usually documented in these esoteric and exclusively expert languages on slide decks and wikis. So, I questioned why we didn’t try to visualize these processes, and why didn’t we make it so that more people can have conversations about concrete artifacts? Can we do that?

And that’s what I’ve been doing with Mars 2020. So it’s a huge 180 from when I first started, and I think that’s the thing that keeps me here. Not only is it that the projects are fascinating, but also just the fact that I don’t feel constrained by one role. The roles I’ve had have been vastly different, thus keeping my interest.

Part Three

Asking Questions and Being Curious

Looking back at your time in the UW design program, what did you find to be the most valuable part of your education, and has it carried on to your work now?

In the Visual Communication program, professors always asked, “Why did you put this element here? What is the reason?” Every single piece had to have a reason, and had to have a story behind it.

The same in the industrial design program. In a physical work, every kind of form factor had to be accounted for and had to have a purpose behind it.

In interaction design, Tad Hirsch (Assoc. Prof. of Interaction Design) and Axel Roesler would also throw us into this world of self-examination, by saying “Why does this story have this part? Why does the movie have this music? Does it need the music?” You’re really forced to think about what it is you’re actually producing.

So, I learned that everything has to have a practical application and a reason behind it—some sort of intention. That’s a thing I really appreciate from the UW Design program. Everything has intent. Because I find myself thinking about purpose all the time. I’m like, you made this slide deck or you’re showing me this model that you created—why? What do people need to take away from this? Let’s talk through that.

Questions aren’t vessels for judgment. They’re instilling trust and a connection to the people you’re trying to help.

Anything in school that you wish you had learned?

I was really surprised by the number of questions I had to ask actual operators at JPL. It was really hard for me to understand what they do in their control rooms, and how they triage off-nominal events. I think that was something really difficult for me starting out: how do I ask the right questions to understand this complex process?

‘Asking questions’ is a hard skill to be taught: I think asking good questions comes from practice and truly understanding how you learn. Yet, it’s so essential in this environment because so much of what I design is embedded in this complex domain that I had zero exposure to previously. But it is so important, because when you have a really good sense of the context in which you’re designing for, your designs are so much stronger.

It’s hard to let go of the fear of asking ‘dumb’ questions. I truly believe now that there is no such thing as a ‘dumb’ question. By asking rudimentary questions, your audience will simply think you’re genuinely curious about what they do. Questions aren’t vessels for judgment. They’re instilling trust and a connection to the people you’re trying to help.

It would have been nice if I had put myself into more classes at UW that were just not design related. I have a much deeper appreciation for the phrase “If you want to be a good designer, don’t read design books.” There should have been a lot more variety in my life to supplement my design education. I think non-design courses would have forced me to be uncomfortable and would have fueled my curiosity. I think I have learned so much at JPL because I have been so severely uncomfortable sometimes.

How do you feel about your experience of the UW IxD program?

I loved being in the interaction design program. It was really hard, but I had a chance to work with some wonderful professors and work within a domain that wasn’t fully articulated yet. Interaction design was still a baby during the time that I attended UW. We were the second group to go through the IxD program, so there was real exploration of “What kind of skills do people need? What are the things we need to teach students?”

The principle that I hope will carry me through my career is the idea of “lowering the barriers.” In interaction design we were always trying to solve problems, like “How can we facilitate communication within a city?” With Pollux, the problem was how to help people frustrated with the antiquated technologies available to them as amateur astronomers. There were always these people-specific problems, and in the world of IxD, it was like, “Yeah, we gotta help people! We gotta figure out what it is that they do, and convey it in a way that a lot of people can understand. So build storyboards or build workflow diagrams!” I loved that aspect of it. That’s what I think is the backbone of what I’m now doing at JPL.

What does NASA JPL look for when they’re hiring designers?

We’re looking for individuals all year-round, so people can send their portfolios and their resumes to us anytime for consideration. For a long time, we were trying to find more senior people to facilitate the group and build the culture, but now we’re actively looking for junior design candidates as well, which is very exciting.

When we’re hiring, we’re most interested in seeing an individual’s design process. I need to see how they solve problems. Sometimes I scan portfolios where everything is beautiful and there are plenty of high-fidelity projects. I love it—I’m a huge fan of nicely displayed artifacts—but I need to see how the designer thinks through a problem.

I’m looking for the artifacts in portfolio that show me “these are the sketches that I made for several different concepts, and here’s why I chose this concept, and these are the individuals that I talked to who gave me insight into how to improve the design.” When I’m able to see all that, I have a lot more questions that I can ask a candidate. I have a lot more confidence that they think about problems holistically.

I also look for sketching. I look for people who come up with creative ways to explain user behaviors, or explain how people perceive certain things—through sketches, storyboards, or workflow diagrams. If you can document your design process and sketching, I will look at it, and I will have questions for you.

I’m also looking for people that are comfortable asking questions. I think that this domain is complicated, and the people here who are operating spacecraft, interpreting telemetry data, or researching climate data from orbiters have been doing so for years. For them, their domain is so familiar, but to an outside designer, asking the basic questions is critical to designing new solutions. I find that the greatest tool one can have when starting at JPL is the ability to be curious and ask questions.