Treating Herpes to Prevent AIDS Transmission

When Dr. Connie Celum walks through the cemeteries in Soweto, South Africa, she is starkly reminded of the AIDS epidemic gripping that country and many of its neighbors.

"It makes an impact when you see the number of graves and realize how many young people are dying," Celum said.

In many parts of eastern and southern Africa, AIDS isn't affecting only high-risk groups like sex workers, she explained. It's become a generalized epidemic. In some countries, between 20 and 40 percent of the adult population is infected with HIV.

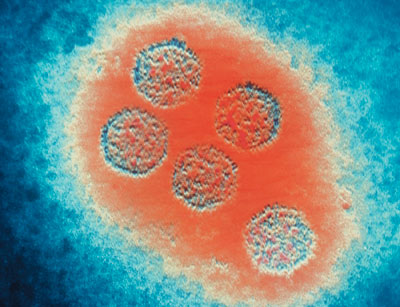

A micrograph of herpes viruses.

"Sometimes the total number of cases is so large, people can't get their heads around it," she added.

High HIV infection rates, however, are just part of the problem facing those who are battling AIDS in the developing world. Though many HIV-positive people in the United States and other developed countries receive life-extending care for their condition, only about 5 percent of the infected population is getting treatment in Africa, where an infection is tantamount to a death sentence.

"Prevention is the key," said Celum, professor of medicine and adjunct professor of epidemiology at the UW. "With such a long road ahead for an HIV vaccine or microbicide, it's essential we look for other methods of prevention."

Celum is leading a pair of studies to determine if acyclovir, a drug used to reduce transmission of genital herpes, can reduce the transmission of HIV. A $30 million grant by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation will fund a study conducted at 12 sites in Africa and India. A grant from the National Institutes of Health will fund another study of populations in the United States, Peru, and three sites in southern Africa.

For the first study, the researchers will recruit 3,600 couples in which one partner is HIV-positive and the other is not, and in which the HIV-positive partner also has genital herpes. Half of the HIV-positive partners in these couples will receive acyclovir, while the other half will get a matching placebo. All of the couples will receive intensive counseling on traditional prevention, such as condom use, and get free condoms and bacterial STD treatment.

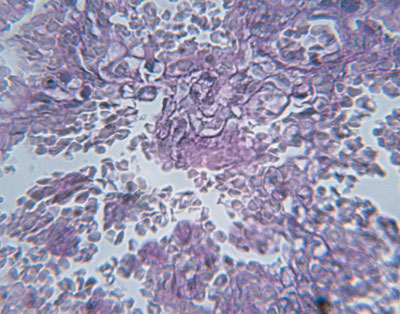

A histological slide shows the cellular effects of an HIV infection.

The study could shed light on the connection between HIV and the herpes simplex virus type 2, or HSV 2, which causes genital herpes. Previous studies have shown that people with genital herpes are about twice as susceptible to HIV infection than the rest of the population, and those with both HSV 2 and HIV shed higher quantities of HIV in the genital tract. This degree of viral shedding makes them more likely to transfer HIV to a sexual partner. Research will help determine if acyclovir can help cut down on HIV transmission in addition to preventing the spread of herpes.

If successful, acyclovir would not only help keep people from contracting HIV and AIDS, it would also be less expensive than treating the disease after infection. A twice-daily course of the generic medication costs about $40 per year for one person. The annual cost is about the same as for one month of generic antiretrovirals used to treat HIV-infected patients.

"If this study determines that an existing and affordable treatment for genital herpes significantly reduces HIV transmission, it will have far-reaching implications for the global fight against AIDS," said Dr. Helene Gayle, director of HIV, TB, and Reproductive Health for the Gates Foundation.

Researchers hope that the study will promote other methods for reducing HIV transmission between couples, Celum said, by incorporating intensive couples counseling. An approach like that is necessary in tackling HIV infection among people in stable relationships because that situation is different, for example, from trying to reduce HIV infection in groups of sex workers.

"If you're not aware of your partner's HIV status, or there's not open discussion, it's hard to get stable partners to use condoms," Celum explained.

The study will counsel couples about condom use and ways to reduce risk of HIV transmission within the relationship. Both groups, those receiving acyclovir and those getting a placebo, will receive this counseling.

The study will also assess biologic factors that affect the likelihood of HIV transmission, including virologic, immunologic, and genetic variants.

The other study will work with HIV-negative people who have genital herpes to determine if taking acyclovir will make them less susceptible to being infected with HIV. The study will take place in Seattle, San Francisco, and New York, as well as at sites in Peru, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa. Celum and her colleagues are recruiting subjects for that study, and expect to finish recruitment by the summer of 2005.