Window on the Retina

Imaging technique reveals retinal cells in a new light

Sciences created a laser imaging technique and used it to discover a cellular structure in the retina. The structure, which the scientists have dubbed a retinosome, is important in the retinoid cycle, a chemical process vital to vision.

|

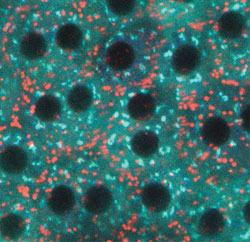

| Scientists are looking inside the eye for new structures. Within the retina is a previously unknown cell structure involved in the retinoid cycle, which is vital to vision. The red-tinted structures, dubbed retinosomes, are distinct from the blue-tinted Golgi, another structure in the retina. |

The research was led by Dr. Yoshikazu Imanishi, a senior research fellow in the UW School of Medicine's Department of Ophthalmology, and Dr. Kris Palczewski, the Bishop endowed professor of ophthalmology, and professor of chemistry. The team included other UW scientists, as well as researchers from the University of Utah and Vanderbilt University.

The group spent the past three years studying the mice retinas, a difficult job because the tissue doesn't survive for long outside of the eye. The scientists designed a low-power pulse laser imaging technique, called two-photon fluorescent microscopy, that could image the retina without damaging it.

Looking into the retina, they found structures containing retinyl esters, an intermediate chemical product in the retinoid cycle. The researchers determined the structures were a storage site for retinyl esters, a characteristic that makes them an important cog in the machine of vision.

The scientists confirmed their results using a genetic test comparing the structures in normal mice and in two types of transgenic mice, one that could not produce retinyl esters and another that could not process the esters. The group's results were published in the Feb. 2, 2004, issue of the Journal of Cell Biology.

Because many vision disorders are caused by defects in the retinoid cycle, scientists hope that a better understanding of that cycle might lead to advances in diagnosing and treating such conditions.

"The biggest problems that we could use this to deal with are declining sight in people as they grow older, and age-related macular degeneration," Palzcewski said.

The imaging method, which Palzcewski hopes will eventually be adapted to humans, could also be valuable in diagnosis, as well as in the development of drug treatments for vision problems. The imaging technique gives an objective view of the retina, which makes it far more accurate than subjective vision tests. The technology also could give scientists a chance to watch the retina at the cellular and molecular levels while administering a drug.

"This is truly a window on the cellular structure of the retina," Palczewski said.