My time as a visiting researcher at UKZN Pietermaritzburg hosted by the Pollination Research Lab has been the most rewarding and exciting experience of my academic career to date! I am beyond grateful for the opportunity to work amongst such an inspiring group of researchers and for the support from all the members of the lab. Thank you specifically for the help and hospitality of Dr. Steve Johnson. I hope to return again!

With the help of Eb Alley, Lindokuhle Mhlongo, Jonah Gula, Preshnee Singh, and Cally Jansen I was able to catch nearly every species of obligate nectarivores targeted in my study. The UKZN PMB animal house at some point these past few months housed Greater Double-collared, Amethyst, Olive, White-bellied, and Malachite sunbirds along with Gurney’s Sugarbirds, Cape White-eyes, and of course some Dark-capped Bulbuls. The only targeted sunbird that never made an appearance was the Collared sunbird.

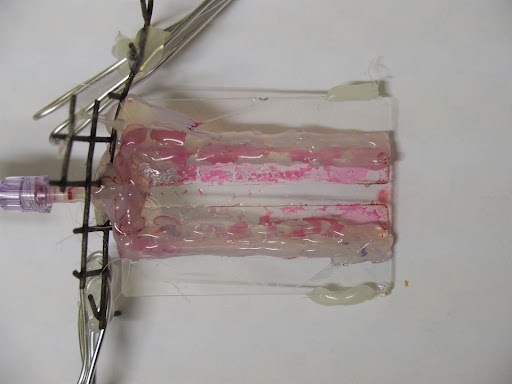

I think all good science starts with plenty of duct tape and some science ends up with even more than the beginning. By that metric my work was very successful! (Although I substituted literal hot glue for my proverbial duct tape…) My experimental setup consisted of a clear artificial corolla filled with nectar and 3 high-speed video cameras aimed at the corolla and bird at different angles in order to get a full understanding of how these birds feed on nectar.

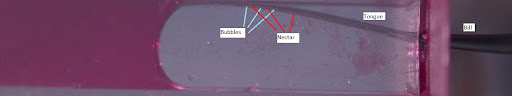

Much of the analysis work remains to be done but initial findings point to an entirely novel feeding mechanism within birds! Based on the videos it appears that sunbirds are employing suction to draw nectar into their bills/mouths before swallowing the aliquot and restarting the process for the next mouthful. This finding may seem like an obvious conclusion, after all humans, insects, and some other animals can suck liquids into their mouth and the morphology of sunbird bills and tongues definitely seem tubular. However, this mechanism has been discounted as improbable or simply impossible due to the rigid nature of bills and the incomplete-tubular geometry of sunbird (and other bird) tongues – mammals can suck because they have cheeks to form hermetic seals with liquid interface (or around tools like straws that humans use). Bubbles seen flowing through the tongue were the first giveaway that something interesting was happening as capillary filling wouldn’t be able to occur with incomplete contact with the nectar reservoir in the corolla. The tongues also are never fully retracted into the bill and are never compressed by the bill tips during protrusion, unlike the elastic filling mechanism used by hummingbirds (which have remarkably similar tongue morphologies to sunbirds at first glance). Again, further analysis is required but this first glance into the feeding mechanisms used by sunbirds indicates another exciting convergently evolved mechanism for nectar consumption within birds.

Along with the first biomechanical study of sunbirds I was able to collect feeding efficiency data from the birds captured for the study. Individuals were presented with nectar at concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% sucrose solutions (by mass). Determining the volumetric and caloric consumption rates for the birds will be useful to consider the mechanics, ecology, and distribution of the sunbird species across different biomes and amongst different flower species.

More work will certainly be done soon and I hope to continue down this fascinating path at the intersection of plant-pollinator interactions, biomechanics, and evolution!

David Cuban is a third year Biology PhD Candidate in the Behavioral Ecophysics Lab. This article is also posted on the UKZN Pollination Research Lab Blog.