When most people think of the University of Washington’s Black Student Union (BSU), they probably imagine a student club that holds meetings and sponsors social events. During the late 1960s, however, the Black Student Union was anything but a typical student club. It was an unstoppable force for social change at the University of Washington and beyond.

The early history of the BSU at UW is an important and inspiring story. This report examines the organization’s origins, activities, and successes, concentrating on the years 1967 to 1969. The BSU led a militant struggle for minority rights at the University. The results transformed the University of Washington, benefiting not just African Americans but also Chicano, Asian American, and Native students. The legacy of the BSU’s activism can still be felt today.

Part 1: Origins

The 1960’s was a turbulent time in American history. Internationally, the United States was involved in the Cold War, dealing with Soviet threats, a Communist Cuba, and the Vietnam War. Domestically, American society faced pressures from a youth counter-culture that questioned both social norms and government policies, and from the civil rights movement of African-Americans and other minorities.1

Acrimony and hostility punctuated the period for activists on both sides of the issues. Those who wanted to maintain the status quo often reacted with violence, which escalated the antagonism. Church bombings, civil disobedience, police brutality, protests, assassinations, and riots marked these years. In tandem with its war abroad, Americans seemed to be in a war with each other.

Seattle was no exception and felt the pressures of change. These pressures became especially acute in the later half of the sixties, as the Civil Rights movement grew. However, Seattle’s civil rights campaigns in the early 1960’s were not as visible as civil rights campaigns in other parts of the United States, such as the South, and white Seattleites continued to ignore the concerns of the city’s black population.2

Yet Seattle’s African-Americans felt the same frustrations as their counterparts nationwide. By the late 1960’s this was especially true for the younger Black generation who were not only frustrated with White America, but also with the leadership of the Civil Rights movement. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Southern Christian Leadership Coalition (SCLC) were criticized by younger activists as elitist, dominated by highly educated lawyers and ministers, and too slow to bring change. “After the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed,” historian Dianne Louise Walker has noted, “the older civil rights section of the movement (SCLC and NAACP) became estranged from the younger activists.”3

The Black community’s frustration was brought to the surface on April 19, 1967, when Stokely Carmichael visited Seattle and spoke to packed audiences at Garfield High School and the University of Washington.4 Carmichael was nationally known as the former chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee –an organization that held sit-ins, voter registration drives and other civil rights campaigns in the South— and one of the leading advocates of “Black Power.”5 His speech inspired young Black Seattleites as he explained Black Power philosophy. Carmichael said, “We must organize black community power to end abuses and to give the Negro community a chance to have its needs addressed.”6 After Carmichael’s visit, young African-Americans began to see their struggle for equality in new ways.

Many whites received Carmichael words with contempt and saw Black Power as synonymous with violent revolt. Some whites even tried to prevent Carmichael from speaking at all. However, the main objective of the Black Power movement was not about revolting against Whites, but rather about African-American self-help. Historian Quintard Taylor explains that “the premise of black power both in Seattle and nationally began with the idea that African-Americans should define and control the major institutions in their community, whose economic and political resources should be mobilized for its development and eventual parity alongside other communities.”7 Black Power, then, was principally about African-Americans exercising more control over their own lives.

Several Black UW students—who would later become the founding BSU members—heard Carmichael speak. In early 1968 when the BSU was founded, members like E. J. Brisker and Eddie Demming credited Stokely Carmichael for catalyzing their activism. Describing Carmichael’s impact, Eddie Demming said: “[Carmichael] had something we could identify with. He told us that things could no longer stay the same.”8 Thus, by the fall of 1967, the University of Washington had several politically conscious, motivated Black students. When these students looked around for an organizational base, all they found was the one Black student organization on campus, the Afro-American Student Society. Founded in 1966 by Dan Keith (an African-American) and Onye Akwari (a Nigerian), its focus was to encourage dialogue and understanding between Black Americans and Black Africans.9 Therefore, students like Brisker and Demming concluded, the Afro-American student Society was not an appropriate organization for political activism.

A key turning point in BSU history came in November 1967 when a group of African-American students traveled by bus to Los Angeles, California, and attended a Black Youth Conference over Thanksgiving weekend.10 Organized by Professor Harry Edwards of San Jose State University, the conference featured two-hundred participants, mostly from colleges and universities along the West Coast, representing various political philosophies: Black Nationalists, Black socialists, Black Panthers, United Slaves (US) and others. It was at this same conference where several prominent Black athletes, including Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then known as Lew Alcindor), voted to boycott the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City to protest America’s racism.11 Several other issues were discussed during the conference, including the concept of Black Student Unions.12 After learning about these organizations, the UW students returned to Seattle intent on establishing their own BSU.13

The primary mission of Black Student Unions was to serve black students’ needs on university campuses, to initiate community service projects, and organize BSUs in high schools and junior-highs.14 Thus, by the end of 1967, there were Black students at UW that had the awareness and motivation to address their concerns, and the program to do so. In early 1968, after returning to school from their winter break, they began their struggle.

Part 2: Emergence

In the first weeks of UW’s 1968 winter quarter, the Afro-American Student Society and the Seattle chapter of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee merged to create the UW Black Student Union . The UW BSU introduced itself in an article titled “New Black Image Emerging.” In this article the BSU stated its intention “to form a power base from which to present certain demands to the University administration.” Its demands revolved around three key objectives: increased minority enrollment, the hiring of more minority faculty, and the creation of a Black Studies program.15

Two fundamental characteristics of the BSU were reflected in this article. The first was its multicultural nature. Although it was called the Black Student Union and always centered on Black interests, the BSU welcomed members of other ethnic groups and advocated for them. The article, for instance, stated that the BSU’s “… members include black students of American and African origin, as well as Indians and South Americans.”16 Multiculturalism was an important element of the BSU from the start.

The other important aspect mentioned in the article was the BSU’s militancy. Initially, the BSU hoped to work in cooperation with the University’s administration to implement change. However, the group noted, if cooperation with University officials proved fruitless, the BSU would take more direct action. Founding BSU member Larry Gossett, explained, “Our militancy is entirely dependent on the white reaction to the concrete proposals we make.”17 In later years, the BSU would make good on this warning and bring an unprecedented brand of student activism to UW.

One aspect of BSU that the article did not mention was the organization’s female membership. During 1968, there were about 20 core members, and at least two of those members were women, Verlaine Keith and Kathy Hallie.18 The reason these and other BSU women often do not show up in articles and other records is because they consciously took (or were given) supportive roles.19 Yet they were vital to the BSU’s activities: answering phones, writing official correspondence, setting up meetings, taking notes, and managing other “nuts and bolts” work.20 Within a year or two the women of the BSU would serve in leadership roles. Although these women were rarely mentioned, they were equal to their male counterparts in their passion and commitment to the movement.21

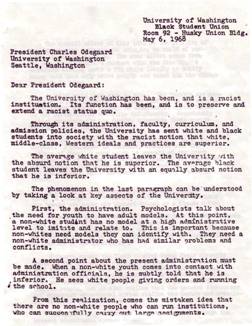

The BSU began to fight for minority rights by taking their concerns to the University Administration and drafting a letter to UW President Charles Odegaard. In this first letter, the BSU called for more black professors, counselors, and teaching assistants; classes in Afro-American History, Culture, and Literature; offerings of African language courses; and a university program for encouraging black students to graduate from college. Additionally, the BSU demanded positive steps be taken to eliminate racism in the athletic department, sorority and fraternity system, housing, and employment (both student and staff), and for the university to be a leader among Pacific Northwest colleges in initiating and sponsoring programs to improve conditions in the black community.22 The BSU closed the letter by saying, “We feel the University of a thousand years does not need another thousand to determine action on these proposals. If you, Dr. Odegaard, do not act promptly, we shall use any means that we deem necessary to insure that freedom and justice prevail on this campus.”23

In this early stage, the UW BSU also worked to establish BSU’s in local high schools and middle schools. Since Seattle’s housing at the time was segregated, with African-Americans and other minorities concentrated in central and south districts of the city, the UW BSU concentrated on schools in those areas. They successfully established BSUs at Cleveland, Franklin, Garfield, and Rainier Beach high schools and Asa Mercer, Meany, Sharples, and Washington junior high schools. Larry Gossett later estimated that by March of 1968, the combined membership of BSUs throughout Seattle totaled around nine hundred youths.24

Part 3: Radicalized

In the spring of 1968 a string of events motivated the BSU to take more aggressive actions. The first of these events was a major student sit-in/protest at Franklin High School on Friday, March 29, where an estimated one hundred students took over Franklin Principal Loren Ralph’s office and forced the school into early dismissal.25 At the head of the protest was Franklin High School BSU members Trolice Flavors and Charles Oliver, and University of Washington BSU members Eddie Demmings, Aaron Dixon, Larry Gossett, and Carl Miller.

The direct cause of this demonstration is unclear. According to Larry Gossett the protest was ignited after school officials expelled two young Black women for wearing the “Natural” or Afro hairstyle on the grounds that it was “unladylike.”26 However, school officials reported the protest followed the suspension of two Black male students after a hallway scuffle the day before.27 The truth of the events are further obscured by the fact that all suspensions resulting from the hallway incident were reversed on the following Monday (April 1) when a Human Rights Commission panel found “discrepancies in the testimony concerning the…suspensions.”28

Perhaps the protest was already planned and the hallway incident the day before was a coincidental occurrence which further angered the students. Certainly there is evidence that Franklin did have significant race problems beyond the dubious circumstances of the alleged fight. In a Seattle Post-Intelligencer article that ran in June of that year, national racism critic, Edward P. Morgan, identified Franklin as a “sick school29.” Regardless of the circumstances leading up to the protest, what is important for BSU history is that following the Franklin sit-in, Aaron Dixon, Larry Gossett, Carl Miller, Trolice Flavors, and others were arrested by Seattle Police and charged with unlawful assembly.30

While sitting in jail Dixon, Gossett, Miller, and Flavors found out that Martin Luther King had been assassinated that same day, April 4, 1968. King’s death had a deep impact on the Black community in Seattle and across the country. Even young activists who criticized King mourned his death. The night of King’s murder Black communities across the country ignited into a fury of rioting, arson and violence. In Seattle, although no major disturbances were reported, emotions ran high and many of the city’s Black youth, infuriated by King’s death, maligned the judge’s refusal to lower the Franklin protest leaders’ unusually high bail and release them.31 The following day, April 5, all of the arrested Franklin protest participants were released. But this did not prevent the inevitable eruption of Black hostility. That night twenty-one arson fires were reported in the Central District alone.32

Soon after their release, Dixon, Gossett, Miller, and others left Seattle for a second Western Black Youth Conference in San Francisco, California, stepping into yet another tense situation.33 Two days after the assassination of King, the Oakland police assaulted the headquarters of the Oakland Black Panther Party. The Black Panther Party was one of the most outspoken advocates of Black Power. The group was known for patrolling Black neighborhoods to protect African-Americas from police violence and providing free breakfast to poor school children. In the ensuing shootout that occurred when the Oakland Police raided the party’s headquarters, eighteen-year-old Black Panther member Bobby Hutton was killed and Eldridge Cleaver, another Panther, was wounded.34

The raid and killing dominated the entire conference. Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panther Party, was a featured speaker at the event and gave a rousing call to action. That speech and the funeral of Bobby Hutton the following day touched the passions of the UW BSU members. More than ever they felt the urgency, resolve and confidence to fight to stop such injustice.

Within two weeks of this second conference, many of the UW BSU members founded the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party, the first chapter outside of California.35 On April 14, 1968,Seale came to Seattle and met with a small group of local activists, many of whom had been active in the UW BSU and Franklin High protest. Seale approved the Seattle Black Panther Party and appointed Aaron Dixon as Captain.36 These events of March and April of 1968—the Franklin protest, the assassination of King, and Hutton funeral—radicalized the BSU and showed them that no progress would be achieved unless risks were taken.

Part 4: Confrontation

By May 1968, the BSU felt the time had come to assert their demands. On May 6, 1968, the BSU drafted a second letter to UW President Charles Odegaard, outlining a list of BSU demands and their justifications. The BSU wrote:

(1) All decisions, plans, and programs affecting the lives of black students, must be made in consultation with the Black Student Union. This demand reflects our feeling that whites for too long have controlled the lives of non-whites. We reject this control, instead we will define what our best interests are, and act accordingly.

(2) The Black Student Union should be given the financial resources and aids necessary to recruit and tutor non-white students. Specifically, the Black Student Union wants to recruit: 300 Afro-American, 200 American Indians, and 100 Mexican students in September.

Quality education is possible through an interaction of diverse groups, classes, and races. Out of a student population of 30,000; there are about 200 Afro-Americans, 20 or so American Indians, and 10 or so Mexican-Americans.

The present admissions policies are slanted toward white, middle-class, Western ideals, and the Black Student Union feel that the University should take these other ideals into consideration in their admissions procedures.

(3) We demand that a Black Studies Planning Committee be set up under the direction and control of the Black Student Union. The function of this Committee would be to develop a Black Studies Curriculum that objectively studies the culture and life-style of non-white Americans.

We make this demand because we feel that a white, middle-class education cannot and have not met the need of non-white students.

At this point, an American Indian interested in studying the lives of great Indians like Sitting Bull or Crazy-Horse has to go outside the school structure to get an objective view. Afro-Americans member of the Black Student Union have had to go outside the school structure to learn about black heroes like Frederick Douglas, W.E.B. Dubois, and Malcolm X.

One effect of going outside the normal educational channels at the University has been to place an extra strain on black students interested in learning more about their culture. We feel that it is up to the University to re-examine its curriculum and provide courses that meet the needs of non-white students.

(4) We want to work closely with the administration and faculty to recruit black teachers and administrators. One positive effect from recruiting black teachers and administrators is that we will have role models to imitate, and learn from.

(5) We want black representatives on the music faculty. Specifically, we would like to see Joe Brazil and Byron Pope hired. The black man has made significant contributions to music (i.e. jazz and spirituals), yet there are not black teachers on the music faculty.37

In the letter, the BSU largely restated the goals that had been part of its program from the beginning: greater minority enrollment, a Black Studies program, and the recruitment of more Black faculty and administrators. Also, BSU’s commitment to multiculturalism showed up in the letter: the recruitment of Mexican Americans and American Indians were explicitly outlined in demand number two and references to Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were cited in demand number three.38 Furthermore, demand number three suggests that the Black Studies Program the BSU envisioned would not just teach about African-American history and culture, but would encompass the stories of other minority groups as well.

The two individuals, Joe Brazil and Byron Polk, that the BSU recommended be hired into the Music department were good candidates. Both were accomplished musicians: Brazil was a saxophonist, flute player, and combo leader, and Polk was also a saxophonist and sextet leader. Furthermore, Brazil was already employed at the UW as an assistant in the Applied Physics Laboratory.39

In response, President Odegaard sent a letter to the BSU stating his support for many of their ideas and willingness to cooperate. On Friday, May 10, representatives of the BSU and the University Administration met for two and a half hours to discuss the BSU proposals. The outcome of this meeting was described as “encouraging.” Carl Miller explained, “Odegaard gave preliminary agreement to our suggestions for implementation of our demands. However, stress should be placed on the word preliminary because there are many details to be ironed out.”40 Mostly, what needed to be ironed out was availability of University funds to support the BSU recruitment goals and other initiatives. The BSU wanted some of its members to be hired as University employees and work recruiting from communities of color. Odegaard claimed that allocating funding for recruiting would take significant time to secure.

A followup meeting was set for BSU members to meet representatives of the Anthropology, Art, English, History, Music, Psychology, and Sociology departments to discuss curriculum for a Black Studies Program. But funding issues also hampered this initiative; the BSU wanted Nathan Ware and James Garrett, experts from California, to help create a Black Studies department at UW. Explaining this, Miller said: “These two men have set up very effective programs in the Bay Area and we feel their expertise will heighten and aid our program.” While agreeing on principle, Odegaard once again resisted the allocation of funds to bring the men to UW.41

During the meeting, 300 BSU sympathizers gathered outside the Administration building (now called Gerberding Hall). At the close of the meeting, they held a rally where many white students voiced their support for the BSU demands, especially the creation of a Black Studies program. Robbie Stern, a Law student, said:

It is terribly important that we be here. It is also important to understand that these demands are in our own best interest as white students because they involve the kind of education we are getting here…the education that we get here is white and middle-class. It is clear at this point that what is happening in the world requires us to have an understanding of non-white America and a non-white world.42

Kathy Halluran of the Black and White Concern Organization declared: “There are 23 million black people in America today and we need to know about them. We are the ones being hurt by the lack of courses on black culture.”43

A week later, the BSU was disappointed to find that their efforts had still not produced tangible results. And with the school year coming to a close, many BSU members believed this was an unacceptable situation. On Thursday May 16, the BSU drafted their boldest letter yet and sent it to President Odegaard. It demanded that he allocate $50,000 for the BSU initiatives and promise to deposit the funds into the BSU account by June 1.44

That evening, E. J. Brisker, the de facto leader of the BSU, telephoned Odegaard’s office. He spoke with Dr. Eugene Elliott, Special Assistant to Odegaard, and outlined the same stipulations of the letter and gave the deadline of twelve o’clock noon the next day (Friday) for the pledge of money. If there was no pledge of money, Brisker warned there would be “new action” to implement their demands.45

Odegaard ignored both the phone call and the letter, which arrived on his desk at 11:40am Friday, and allowed the deadline to pass without any statements. The BSU then decided to take its demands to Washington Gov. Dan Evans, who happened to be on campus. After negotiating with Dr. Elliott, UW Vice President Ernest Conrad, and Faculty Senate Chairman Charles Evans, E.J. Brisker was allowed to hand the letter of demands to Governor Evans. After doing this, Brisker turned and left; Evans, appearing unperturbed, said nothing46.

Part 5: Direct Action

In the afternoon of the following Monday, May 20, a large group of BSU members and their supporters entered Odegaard’s office suite at approximately 5:20pm.47 They expected to find Odegaard and Gov. Evans there, and they intended to keep the men in the office until their demands were met. Instead the BSU members found that they had interrupted a Faculty Senate Executive Committee meeting and Evans was not present.48 Several protesters entered the meeting room and sat on the floor while others secured the suite. The subject of the meeting immediately changed to the BSU’s demands and continued with hostile exchanges.49 By 6:40pm the discussion had stopped, Odegaard and most of the other administrators withdrew into the inner office and were barricaded in by protesters. This left the protesters in the outer-office, along with a few faculty members from the meeting who decided to stay and help the protest. The most prominent of these faculty members was Professor Arval Morris50.

By 7 pm, the number of sit-in participants had grown to 150. Most of the students involved were young African-Americans, but some non-Blacks (such as Robbie Stern) were also involved. In spite of the efforts of the University’s Police Department to cut off the activists, protesters and supplies (such as groceries and a record player) were lifted up to the third story office by ropes outside the building. By 7:30pm the Seattle Police had arrived on the scene and helped UW police seal off the building.

At 8:15 p.m., Vice-President Donald K. Anderson and UW Police Chief Ed Kanz tried to deliver an ultimatum to the protesters: telling them to either leave on their own by 8.30pm or they would be removed by force. But this exchange was hampered by the heavy office doors that separated the protesters and the police. Around this time Michael Rosen, an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer who had helped Miller, Dixon, and Gossett in their case following the Franklin protest,51 arrived on the scene and began to establish negotiations.52 With the help of Rosen and the sympathetic faculty members, Brisker, Dixon and the BSU drafted a proposal that would meet their objectives. The proposal was delivered to Odegaard, negotiations continued, and at 8.45pm Brisker announced that Odegaard had signed the BSU proposal and the sit-in was over.53 The protesters left Odegaard’s office chanting “Beep-beep, bang-bang, ungawa, Black Power!”

Part 6: Results

University officials tried to downplay the sit-in. They asserted that they had not been forced to accept BSU demands but rather had merely restated preexisting policy.54 To some degree this was true. Odegaard had publicly urged the University community to be more aware of race problems as early as 1965.55 However, the sit-in marked a major turning point in UW policy. Even if it was a restatement of existing commitments, it was a very important restatement. Without the administration’s agreement to the BSU’s proposal, the positive measures that followed the sit-in would not have taken place in such an expeditious way—if at all or ever.

Within a year’s time, the focus of the University had taken an undeniable new shift with the entire BSU program being implemented. One clear result was an unprecedented jump in enrollment of people of color. This was due to a new program, established in the sit-in’s aftermath, called the Special Education Program (SEP). Dr. Charles Evans, head of the Microbiology department and the Faculty Senate Chair at that time, was appointed by Odegaard to direct the SEP program. Its purpose was to correct the fact that white students were far more likely to attend college that their counterparts of color56. The program included recruitment of new students, tutoring and advising services for students after enrollment.

BSU members were hired by the University to lead the recruitment effort. During the summer of 1968 these BSU members looked for young adults with college aspirations in African-American communities, such as in Seattle’s Central District. However the BSU recruiters were also active in Washington’s Yakima Valley and the Makah Indian Reservation, in order to reach the Chicano and Native American communities.

Due to these efforts, African-American enrollment at UW increased 310%, from 150 students in autumn of 1967 to 465 one year later57. Enrollment of Native Americans rose from approximately 25 to 100 and the Chicano student body went from 10 to 90 undergraduates over the same period58.

Once these newly recruited students entered the UW they saw that they had been deprived the necessary preparation to be successful in college. Therefore, another important part of the SEP program that began that year was tutoring. Regular tutoring in a variety of subjects, and special preparatory English and math courses, were established to help students of color be successful.59

The aftermath of the sit-in also saw dramatic increases in the number of University of Washington faculty and staff of color. Black UW employees rose from 327 in January 1968 to 493 in October 1968. Black faculty rose from 7 to the all time high of 15 by 1969, with new professors in the Urban Planning, Medicine, Dentistry, and Engineering departments60.

The movement to institute a Black Studies program had support from UW faculty members even before the sit-in. Thus, after the sit-in, the program quickly took shape. The Black Studies program that started that autumn included courses in Swahili, an Anthropology class called “Social Biology of the American Negro” and a Social Science class “Afro-American History and Culture61.” With its visions set in motion, the BSU was victorious.

Conclusion

The Black Student Union deserves a special place in the history of the University of Washington. The record of its first year is nothing less than remarkable. With exemplary determination and extraordinary success, the BSU was the first organization on campus to militantly advocate for people of color. Within one year this student organization transformed the University into a place that concretely addressed racial inequality. Despite initial resistance, all of the BSU demands were eventually implemented by the administration, leaving the UW profoundly changed.

All too often history is conceptualized as something dead and gone, with no affect on the present. However, with the BSU’s story, it is easy to see the connection between the past and present: many of the programs implemented after the sit-in still exist today. In 1970, Samuel E. Kelly was appointed the first Vice President of Minority Affairs, and under his Office of Minority Affairs (OMA) these post sit-in reforms were coordinated together. During this time SEP became the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) and continued to provide recruitment and retention support for underrepresented UW students (including poor whites).62 The tutoring services were also brought under the supervision of the OMA in 1970, and in 1976 the tutoring services were further consolidated into the Instructional Center (IC).63 All of these entities—OMA, EOP and IC—can be found at UW today.

Another result of the BSU’s legacy is the UW’s current American Ethnic Studies department. The successful creation of the Black Studies program encouraged students to demand Chicano and Asian-American Studies programs. Later, the Black Studies program merged with the Chicano Studies and Asian-American studies to create the department of American Ethnic Studies64. Therefore, the American Ethnic Studies department also owes a debt of gratitude to the Black Student Union.

Finally, the BSU legacy also includes the Ethnic Cultural Center. It was completed three years after the sit-in to give students of color a much-needed place to feel comfortable,65 and it is yet another modern day monument to the efforts of the BSU. Taken together, all of these outcomes illustrate the fact that the Black Student Union made important contributions to the University of Washington.

Copyright © Marc Robinson 2008

Works Cited

Angelos, Constantine. “Human-Relations Unit Urged at Franklin High.” The Seattle Times. 1 April 1968 pg. 8.

Berkeley in the Sixties. Mark Kitchell, Dir. California Newsreel, Kitchell Films: 1990.

Bryant, Hildeu. “A White University?” Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 4 June 1969 pg. 14-15.

Carson, Clayborne. Civil Rights Chronicle: The African-American Struggle for Freedom. Lincolnwood, IL: Legacy Publishing, 2003.

Carlson, Dennis. BSU Meeting with Odegaard ‘Encouraging.’” The Daily (University of Washington). 14 May 1968 pg. 1.

Cour, Robert. “UW Negroes Air Demand for $50,000.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 18 May 1968 pg 1.

Cour, Robert and Walter E. Evans. “Carmichael Rips Into Whites Here.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 20 April 1967 pg 1,7.

Crowley, Walt. Rites of Passage. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Curtis, Cathleen. “The Black Revolution.” Tyee Magazine. Winter 1968 pg.1-12.

Doctor, Dave. “New Black Image Emerging.” The Daily (University of Washington). 15 Feb 1968 pg 6-7.

Emery, Julie. “U.W. Black Students Detail 5 Demands.” The Seattle Times. 9 May 1968 pg 13.

Ferbon, Dave. “Late-Hour Compromise Averts Sit-in Violence.” The Daily (University of Washington). 21 May 1968 (no. 112) pg 1,11.

“Four in Franklin Protest Plead Not Guilty.” The Seattle Times. 5 April 1968 pg 24.

Gossett, Larry. Interview with Author. 23 Oct. 2003.

Gossett, Larry. Interview with Author. 13 April 2004.

Gossett, Larry. Interview by Trevor Griffey and Brook Clark. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. gossett.htm Interviewed on 16 Mar & 3 June 2005. Accessed: 05 July 2006.

Hannula, Don. “Non-Franklin Students Led Negro Sit-in, Says Principal.” The Seattle Times. 30 March 1968, pg. 13.

Kelly, Samuel E. “Annual Report of the Office of Minority Affairs for the Academic Year of 1970-71.” WU Vice President for Minority Affairs. University of Washington Archives, Seattle, Washington.

“Letter from BSU to Odegaard, May 6, 1968”. Black Student Union. University of Washington Archives, Seattle, Washington.

“Letter from BSU to Odegaard, May 16, 1968”. Black Student Union. University of Washington Archives, Seattle, Washington.

Mack, Kathy. “Black Women Tell Ordeals in Climbing Out of ‘Cruel Valley.’” The Daily (University of Washington). 22 Apr 1969, pg 8,16.

McCune, Cal. From Romance to Riot: A Seattle Memoir. Seattle: The Author, 1996.

Norton, Dee. “Agreement Ends Student Sit-in.” The Seattle Times. 21 May 1968 pg. 5.

“Olympic Boycott Voted by Negroes.” New York Times. 24 November 1967 pg. 30.

Pitre, Emile. Interview with Author. 17 Oct. 2003

Prugh, Jeff. “Negro Group Votes to Boycott ’68 Olympics.” Los Angeles Times. Nov 24, 1967 part III pg 1,8.

“Report of Friends of the Educational Opportunity Program From 1970-1974.” UW Vice President of Minority Affairs. University of Washington Archives, Seattle, Washington.

Rogers, Ray. “Olympic Boycott Prime Topic of Negro Parley.” Los Angeles Times. 23 November 1967 part II pg 3.

Sieverling Bill, Forrest Williams. “Four Men in Franklin High Case Release Without Bail.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 6 April 1968 pg 3.

Smith, Lane. “Black Community Power Will End Abuses, Says Carmichael.” The Seattle Times. April 20, 1967 pg 5.

Taylor, Quintard. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 18710 through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994.

Walker, Dianne Louise. The University of Washington Establishment And the Black Student Union Sit-in of 1968. Thesis (M.A.), University of Washington: 1980.

“White Racism Critic Calls Franklin ‘Sick School.’” Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 29 June 1968 pg 3.

Wyne, Mark. “’Harassment Fires’ But No Riots Occur Here.” The Seattle Times. 6 April 1968 pg 13.

1 Berkeley.

2 Walker, 46.

3 Ibid., 34.

4 Cour and Evans, 1.

5 Carson, 184.

6 Smith, 5.

7 Taylor., 217.

8 Doctor, 6.

9 Curtis, 3.

10 Gossett, 23 Oct. 2003.

11 “Olympics,” 30; Prugh, 1.

12 Rogers, 3.

13 Gossett, 23 Oct. 2003.

14 Walker, 37.

15 Doctor, 6.

16 Ibid., 6.

17 Ibid., 7.

18 Gossett, 13 April 2004.

19 Mack, 17.

20 Gossett, 05 July 2006.

21 Mack, 17.

22 Curtis, 4.

23 Ibid., 4.

24 Gossett, 23 Oct 2003.

25 Hannula, 13.

26 Gossett, 23 Oct. 2003.

27 Hannula, 13.

28 Angelos, 3.

29 “White,” 3.

30 Gossett, 23 Oct. 2003.

31 “Four,” 24

32 Wyne, 13.

33 Crowley, 114.

34 Berkeley.

35 Gossett, 05 July 2006.

36 Crowley, 114.

37 “Letter, May 6, 1968.”

38 Ibid., 13.

39 Emery, 13.

40 Carlson, 1.

41 Ibid., 1.

42 Ibid., 16.

43 Ibid., 16

44 “Letter, May 16, 1968.”

45 Cour, 1.

46 Ibid., 1.

47 Bryant, 14; Ferbon, 1; Norton, 5.

48 Gossett, 05 July 2006.

49 Norton, 5; Walker, 2.

50 Norton, 5; Walker, 66.

51 “Four,” 24.

52 Walker, 66.

53 Bryant, 14; Ferbon, 1; Norton, 5.

54 Walker, 5.

55 Ibid., 47.

56 Bryant, 14.

57 Taylor, 223.

58 Walker, 73.

59 Kelly, 3-4.

60 Taylor, 223; Walker, 47.

61 Curtis, 4-5.

62 Kelly, 4.

63 Pitre.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Crowley, 170.

67 McCune, 106-7.

68 Ibid., 107.

69 Crowley, 136.

70 Ibid., 137.