The Christian Friends for Racial Equality (CFRE) was a unique and pioneering organization in Seattle’s civil rights history. Founded in 1942, the Christian Friends was a product of the reaction of Christian social activism to Seattle’s intergroup1 tensions of the late nineteen‑thirties and World War II. CFRE used education as a way of combating prejudice and discrimination. However, the group’s main focus was on positive social interaction across race and religious boundaries. This approach to race and religious relations set CFRE apart from other civil rights groups and fostered the niche in which the Christian Friends would flourish for the next thirty years. The Christian Friends realized that improving race and religious relations in Seattle also involved fighting discrimination through actions such as meeting with businesses, writing letters to legislators, and supporting other civil rights groups, but for the most part, CFRE left the legal and direct action battles to other organizations. Though rarely involved in legal campaigns, CFRE pioneered in race and religious relations and laid the groundwork, in terms of community attitudes, that allowed political and legal campaigns to be successful in the Seattle area.

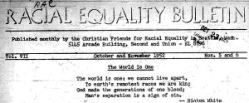

Much of the success of the Christian Friends can be credited to the work of its dedicated volunteers. With their help, CFRE staffed an office, published the monthly Racial Equality Bulletin, organized educational meetings and social gatherings, and performed community outreach. The unique membership profile of CFRE indicates why the organization enjoyed this volunteer base. Approximately two‑thirds of the organization was female and senior citizens also composed much of the group. During the years CFRE was active (1942‑1970), many women were housewives and could volunteer time to support CFRE. Most retired senior citizens had the opportunity to volunteer their time and their expertise in certain fields.

Prior to World War II, Seattle had acquired a reputation as a racially liberal city. Compared to the regimented and confrontational race relations of the Southern and Eastern parts of the United States, Seattle’s racial climate was much more benign. However, people of color were rarely given the same opportunities and privileges of Seattle’s white population. People of color were limited to menial occupations, their housing was restricted to limited areas of the city and they were excluded from certain recreational activities. However, they were seldom denied service at restaurants and businesses. The relatively small population of color in Seattle before the war was responsible for keeping race relations from reaching the point of confrontation. In the face of “polite” discrimination, African Americans, Asian Americans and other groups of color forged their own cultural communities that gave participants a purpose and a place. Small businesses, newspapers, theatre groups, mutual aid organizations, nightclubs, sports teams and churches were part of the cultural community that sustained populations of color.2

World War Two changed the Seattle scene dramatically. One of the most significant and lasting changes was in the population. Military bases and industrial production attracted young men and women from all over the nation. Seattle’s pre‑war 1940 population of 368,302 increased 44 percent during WWII to reach 530,000 in 1944.3 Seattle’s population decreased to 467,591 by 1950, but proportionately more people of color continued to reside in Seattle after the war, substantially raising the percent population of colored people relative to the total population between 1940 and 1950. Most notably, Seattle’s African American population grew by 400% between 1940 and 1950.

The large influx of people of color during the WWll years affected both the white and the pre‑existing population of color. LeEtta Sanders King (for many years an active CFRE member), described the feelings of Seattle’s established black community regarding the newly arrived blacks:

I was quite ashamed of them. They looked so bad… I tried not to see them… We felt that they don’t need to come up here in our wonderful country and spoil things. There was a feeling of the people that were here of resentment against them, the ones that were coming in. Because they were messing things up.4

The local black newspaper, Northwest Enterprise, expressed similar concern when it said “as long as one member of our race compels criticism from other races for being uncouth, ignorant, and dirty, so does our entire race receive a full share of that criticism.”5 Despite the resentment towards the newcomers, the migrants would soon become integrated into Seattle’s black community and assume leadership roles. Reverend Fountain W. Penick arrived in 1942 and the attorney Charles Stokes in 1944. These men, both of whom became prominent CFRE members, were leaders of Seattle’s black community; Penick, through the church, and Stokes as Seattle’s first black legislator.6 Organizations such as the Association for Tolerance (1943) and the Fellowship Committee of black churches (1944) were created to help the integration process.7

Segments of the white population of Seattle responded to the influx of people of color in various ways. Some refused service to people of color, hanging signs reading “We Cater to Whites Only.”8Restrictive covenants prohibited people of color from moving out of the Central District and into white neighborhoods. In many cases, if a family of color were able to move into a previously all‑white neighborhood, the white neighbors would circulate petitions, harass and threaten the family of color in an effort to force the family to leave.9 The signs and the petitions are evidence that Seattle’s once discreet and “benign” racism was becoming more overt as larger numbers of people of color moved into the area.

The more outright racism led to a confrontational atmosphere that began to affect community relations negatively. In response, groups and organizations such as the American Friends’ Service Committee, the Race Relations Department of the Seattle Council of Churches, the Anti‑Defamation League and the Christian Friends for Racial Equality were formed to foster better race relations in Seattle. Other organizations, like the NAACP, the Japanese American Citizens League and the Seattle Urban League, experienced an increase in membership. At the request of private race relations groups, Seattle’s Mayor Devin created the Seattle Civic Unity Committee in February of 1944. This committee, like the others springing up across the nation at that time, responded to complaints of discrimination, exerted influence over race‑relations public opinion in Seattle, and was a leader and coordinator of positive race relations efforts throughout the city.10

It was this scene that Victor Carreon entered. He had been a student of the American Baptist missionary Edith Steinmetz in the Philippines. Her teachings on democracy, drawn from the Bible and the United States Constitution, inspired Carreon to “LIVE the Christian life.”11 After teaching in the Philippines for several years, Carreon came to Seattle to earn a college education. But when he arrived in the U. S., the democratic conditions described by Steinmetz were sorely lacking for people of color. Excluded from housing, employment and recreation, Carreon’s greatest disappointment was the ill treatment he received in Seattle churches.12

Steinmetz’s first meeting with Carreon since in the United States was in a Filipino Christian Fellowship in 1939. He told her of his troubles and the similar plight of people of color in Seattle. He asked Steinmetz for her help to bring together Christians of various races and denominations to meet to discuss their problems and work towards their solutions.13

During the fall of 1939, twenty‑five persons gathered together for the first of the monthly luncheon programs at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Those twenty‑five included African Americans, Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Filipino Americans, whites and a Native American. The monthly luncheons featured speakers describing the conditions and problems of local racial groups. Attendance varied from a dozen to over thirty. In addition to informing those present about local racial conditions, the small luncheons gave a much valued opportunity for friendships to form regardless of racial lines.14

Common agreement ended the preliminary meetings in May of 1942. On May 19, 1942, seventeen people met to form an independent self‑governing organization: Grandino Baaoa, Bertha Campbell, Victor Carreon Nella Carter, J. J. Chan, Emma Chainey, Betty Flohr, Rev. Paul Fong, Judson Grant, Helen Harris, Hester Miller, Rev. and Mrs. F. W. Penick, Dr. and Mrs. Fred Ring, Lew Soun, and Edith Steinmetz.15 Seven Christian denominations and the Jewish faith were represented as well as the previously mentioned people of color from the luncheon except for Japanese Americans who were interned during WWII. It was the friendships that had formed during the preliminary meetings that inspired the name Christian Friends for Racial Equality.16

The tenets of the Christian Friends were established during this first year. There would be no dues in order to allow anyone who believed in the principles of CFRE to be a member. Donations, fundraisers and volunteer work supported CFRE for the next thirty years. CFRE’s Statement of Purpose was formulated in this first year.

As Christian Friends for Racial Equality, we seek to apply the Golden Rule.

We stand for the equality of opportunity for all men of all races to exercise all rights and privileges guaranteed by our Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

We protest by all peaceful means the denial of those rights and privileges, and strive to develop a public conscience against racial and religious discrimination.

We endeavor to promote understanding by social acquaintance.

Toward this end we, Christian Friends, seek to welcome all people to our churches, and to strengthen those bonds which unite us all as one people in our democracy.17

The Statement of Purpose remained virtually unchanged for the next 28 years, except for a clause added in the forties that placed greater emphasis on social contacts. CFRE’s Statement of Purpose was its guiding light, directing the group’s endeavors and focusing its energies on what was essential and important to the organization. During the first year, CFRE also established that monthly meetings were to be held the third Tuesday of each month at churches of various denominations around Seattle.18

The Constitution of the Christian Friends was adopted in 1943.19 This document described the positions of the elected officers: president, first and second vice‑presidents, recording secretary and treasurer. The officers were elected to two‑year terms at the Annual Membership Meeting in May. The executive board was to be composed of the elected officers, representatives of the standing and special committees, at least six ministers from various races and denominations, five directors‑at‑large and certain persons representing organizations conducting similar work. The following standing committees were designated: finance, membership, publicity, program, music and hospitality. In addition to the standing committees, special committees were described that were to deal with specific concerns: anti‑discrimination, restrictive covenants and community attitudes, legislative and fine arts.20

Set forth in the constitution was a three‑part program of activities and techniques employed by CFRE to help eliminate racial and religious discrimination in the Seattle area. To foster better community relations, the promotion of understanding through social acquaintance was designated as a “vital part” of CFRE. Social acquaintance could be fostered at monthly meetings during the social hour and conducted by individual members by talking with people outside their usual social group. Seeking to educate the community about racial and religious issues, CFRE’s educational program included speakers (both CFRE members and guests) at monthly meetings, the sending of speakers from the CFRE Speakers’ Bureau to talk to various community groups and the distribution of educational literature. To respond and deal with discrimination, CFRE used these methods:

a) By direct non‑violent action without demonstration of anger, but by seeking to develop understanding rather than resentment.

b) By the procedures of investigation, persuasion, and when advisable, by publicity.

c) By welcoming the cooperation of other individuals and organizations in the mutual working out of community problems, remembering that the matter of credit for accomplishment is of little concern.

d) Endorsement of projects by other organizations shall be subject to the approval of the Executive Board.

e) This organization recognizes no difference in individuals because of the race or creed and this position is the basic test of its decisions and attitudes.21

The ease with which one could join the Christian Friends, the non‑confrontational agenda and the social emphasis made CFRE a very popular group. Membership climbed from the original seventeen charter members to 500 in the first four years.22However, due to the lax membership qualifications, members were not necessarily active in the local group. Steinmetz noted in her “Twenty Years History of the Christian Friends for Racial Equality,” that a number of WWII servicemen were among those who signed membership cards. She hoped that the servicemen would spread the CFRE message around the world.23

Another factor that helped increase membership was the prestige value of the Christian Friends. CFRE sought to extend influence over the local community by enlisting the support of popular community leaders as allies. These allies were listed as “sponsors” on CFRE letterhead (there were about thirty at a time). The role of sponsor did not include duties, except to promote and support the Christian Friends; thus sponsorship was different from serving on the Executive Board (which was later listed on CFRE letterhead when the system of sponsorship was dissolved). A December 20, 1946 letter to Stimson Bullitt from CFRE thanked him for “the use of [his] name as Sponsor, and for the added strength [that this gave the CFRE] effort.”24

The sponsors of CFRE were both male and female and represented many races, religions and social backgrounds; all were active in improving race relations in Seattle. Arthur G. Barnett was president of the Seattle Civic Unity Committee and the trial lawyer for Gordon Hirabayashi in the losing Supreme Court Case that challenged the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII.25Stimson Bullitt was a member of the wealthy and prominent Bullitt family. His mother, Dorothy Bullitt, had founded KING broadcasting and the family was well known for their community service and charitable activities. Bertha Campbell, a charter member of the Christian Friends, was also an early board member of the Seattle Urban League and a founding member of Delta Sigma Theta, one of the largest African American sororities in the nation.26 Dr. Felix B. Cooper was one of the founders of the Seattle Urban League.27Dean E. Hart served as the executive secretary for the Seattle Urban League.28 Letcher Yarbrough was the president of the Seattle and Washington state chapters of the NAACP, appointed to the Civic Unity Committee and active in the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the Urban League and CFRE.29

With the support of so many prominent civil leaders in Seattle, the membership and activities of the Christian Friends soared. By its fourteenth year (1956), CFRE had become the largest interracial civil rights organization in Seattle’s history.30 CFRE had a membership advantage because it included people who were excluded from other civil rights groups. Whites felt comfortable in CFRE because it was interracial and not focused on a single race. Women were not marginalized in CFRE; they composed much of the membership and frequently served in high leadership positions.

Many of the members of the Christian Friends were active in other civil rights and community betterment organizations. This indicates several things about CFRE and its members. Firstly, it shows that in addition to official coordination with like‑minded groups, cross‑membership expanded cooperation between the organizations. Secondly, cross‑membership indicates that CFRE performed a function that was not served by the other organizations. Thus, CFRE occupied a niche in the Seattle community. The social focus of the Christian Friends was its rare and appealing function. The Christian Friends aimed to create an enjoyable social environment in which interracial and interfaith exchanges could take place. CFRE organized theater outings, small teas and luncheons, picnics, nature walks, folk dances and art classes. These interracial social activities supplemented the educational and political work of the Christian Friends and other civil rights organizations, making CFRE attractive to members of other groups.

Women were particularly active in CFRE and composed approximately two-thirds (67%) of its membership and 72% of its officers.31 The Christian Friends appealed to women not only because of its commitment to civil rights and Christian Brotherhood, but also for the social activities and the leadership and volunteer possibilities that were not available to them in many other organizations at that time.

Women may have had an advantage over men with regards to participation in CFRE. During the nineteen‑forties, fifties and early sixties, many women were housewives. These women had much more unallocated time than a person who was working a full‑time job (typically males). Flexible schedules allowed these women to perform volunteer work and to be more active in the organization than many men (retirees are one large exception). CFRE did not have dues and thus did not receive much money beyond the minimum to keep the organization running. In CFRE, volunteer work was essential to maintain the organization. Though the Christian Friends were occasionally able to hire a part‑time secretary, volunteers performed much of the office work. Not only did volunteers staff the downtown office five days a week, but they also mimeographed, hand addressed and postmarked the Racial Equality Bulletin n (REB). CFRE volunteers in committees coordinated speakers for meetings, planned music and entertainment, organized social events, researched racial conditions in Seattle, compiled the Racial Equality Bulletin, publicized CFRE’s work and encouraged new membership. The volunteer base allowed the Christian Friends to accomplish as much as it did.

Retirees helped to meet this demand for volunteer support. A large number of CFRE members were senior citizens. The REBcarried obituaries of its members, noted when members were ill and occasionally listed members’ ages. The large number of illnesses and deaths in the membership suggests that there were numerous senior citizens in the group. Additionally, a newspaper article about CFRE described many of its members as belonging to “an older generation.”32 Many men who were active in CFRE almost certainly had to be retired in order to donate so much of their time to the organization. This was the case of charter member Dr. Fred Ring, CFRE member and civic leader Dr. Felix B. Cooper and CFRE president (1957‑1959) P. Allen Rickles.33

The large presence of retirees supports the idea that CFRE, while it was a liberal organization, used conservative methods in its approach to better interracial and interfaith relations. The Christian Friends did not organize sit‑ins, rallies or demonstrations to further its agenda. Rather, CFRE held lectures and distributed pamphlets to educate the community.34 Through this method, the Christian Friends garnered more widespread support than if the organization had chosen a more radical method.

Middle and upper social classes were drawn to CFRE because of its more conservative methods. The role of sponsors in CFRE also attracted persons who aspired to the same commercial and civic prominence as the sponsors. Many of the African Americans involved in CFRE were those who had been living in Seattle prior to WWII. These people saw themselves as members of the upper class of Seattle’s African American community; most of them were not confrontational in their approach to race relations. Interracial organizations such as CFRE appealed to these people.35

There is not much data as to the social class of members, except that one can infer that primarily membership came from the middle and upper classes. The members written about in the REBinclude doctors, professors, lawyers, ministers and other professionals. Judging from the education program of CFRE, the lectures, the panel discussions, suggested reading lists and the news items in the REB, the content of CFRE was geared for a well‑educated membership. Finally, CFRE chose traditionally upper-middle class social activities such as theater outings, spring teas and folk dancing.

The racial composition of CFRE is hard to determine. Members were never listed as R. Johnson (black) and C. Johnson (white) when described in the REB. However, other associations that members belonged to, like NAACP and Jack and Jill, were written about in the Bulletin and pictures of members were sometimes published in obituaries. According to this data, there seems to have been a fairly even number of whites and African Americans in CFRE followed by a small number of Japanese Americans, Chinese Americans, Native Americans and Mexican Americans. For the most part, it seems that the elected officers reflected the composition of CFRE. One exception is that, though they served as officers, no African American held the position of president until Mrs. Albert Chaney was elected in 1961 (the group’s nineteenth year).36

Though named the Christian Friends for Racial Equality, the organization had a number of Jewish members.37 One of the charter members of CFRE was Jewish (unnamed) as was executive board member Rabbi Joseph Wagner (1955‑1957) and one of CFRE’s most beloved presidents, P. Allen Rickles (1957‑1959).38Jewish participation in racial and religious equality groups had historically been strong in the Seattle area. In addition to founding their own civil rights organizations, like the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle, the Jewish community of Seattle was also active in the Seattle NAACP. The Jewish community was subject to many restrictions because of its faith and was among the first to benefit from civil rights legislation. The Christian Friends welcomed its Jewish members as equals, they held meetings in Jewish temples and even changed their name in 1967 to Christians and Friends for Racial Equality to allow “Buddhists, Unitarians, Jews and others [to] feel free to join.”39

CFRE’s membership profile was distinct from other civil rights groups: two‑thirds of the group was female and there were many senior citizens active in CFRE. The group was primarily white and African American with a small number of members from other races. The Christian Friends was geared toward the middle and upper social classes in terms of content, activities and methods. In comparison, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a national, interracial organization spanning the same dates as CFRE had a different membership profile. Seattle CORE members tended to be between 20 and 40 years old, had low levels of religious affiliation, were of middle and upper class levels and well‑educated; approximately half were white and the group was equally mixed male and female.40 Most of the membership of the Seattle Branch of the NAACP was African American. Judging from membership lists, a range of classes were represented, from attorneys and ministers to cosmetologists and mail carriers, however among the leadership positions, there was a much greater concentration of professionals. Officers of the Seattle NAACP were almost equally mixed male and female, but the Executive Board was predominately male (over several years, the board averaged 85% male representation). However, the general membership was more equal, 65% male and 35% female and the volunteers were actually 70% female.41Comparing the membership of CFRE to other civil rights groups like the NAACP and CORE helps to illustrate the niche filled by the Christian Friends.42 CFRE differed from traditional organizations governed by men, from the student civil rights groups, from purely political organizations and from groups catering to a single race. In CFRE’s inclusive niche, many came to participate.

The Christian Friends for Racial Equality had an extremely close relationship with Seattle churches. Victor Carreon came to Edith Steinmetz in 1939 because he felt left out of Seattle’s Christian community.43 One of the major reasons CFRE was formed was to address the issue of discrimination in Christian churches. Christian Friends believed that the church should be a community leader in ending discrimination and in emphasizing the idea of brotherhood regardless of race or creed.44 Thus CFRE took on the role of educating and encouraging the church to be a leader in promoting positive race and religious relations in Seattle.45

To facilitate a close working relationship with Seattle churches and to foster the inter‑faith atmosphere, CFRE decided to hold its monthly meetings in different churches throughout the city.46 Usually members of the church congregation (though not necessarily involved with CFRE) attended these monthly meetings and helped organize the social hour. This allowed those outside of CFRE to become familiar with CFRE’s purpose and activities.

CFRE created the Church Relations Committee in 1952 to determine how best to coordinate the interests of the churches with CFRE’s work in the race relations field. This committee was composed of representatives from various denominations and churches.47 One of the projects of the Church Relations Committee was to mail out 250 letters to ministers and to chairs of churchwomen’s associations that expressed a desire for a closer relationship between CFRE and the churches, especially in the field of human rights.48 The committee encouraged the idea that ministers envision their church community as including not only the members of the congregation but also those living in the nearby area. The church should minister, through out‑reach programs, to its whole community.49

The discussion panel at CFRE’s March 1955 meeting pondered the question “What Should the Church do in Answer to Seattle’s Intergroup Problems?” Three main points emerged from the discussion: the church should strive to make newcomers, regardless of background, welcome; churches with homogenous backgrounds should strive to understand other people and groups; and churches should lead, in word and deed, the process of breaking down exclusive, all‑white communities.50

Another method of maintaining close contact with the church leadership was to appoint six ministers to the Executive Board of CFRE.51 This ensured that the Christian Friends and the ministers were keeping in contact with each other’s activities and were aware of each other’s concerns. In several cases, CFRE would introduce a concern to the ministers and ask for their help in taking action. Ministers were asked to take the concern to their congregations and enlist the congregation’s support. For example, ministers had their congregations sign petitions asking Seattle City Council to legislate against racial restrictions in cemetery policies. The Puget Sound Association of Congregational Christian Ministers went on record against racial restrictions and also resolved that its name could be used by CFRE to protest discrimination.52 The help of ministers was also asked for in the case of housing. CFRE asked ministers of white congregations to “encourage the property owners in their churches to signify their willingness to sell or rent to persons in minority groups” and asked ministers of congregations of color to “make available a list of their members who wish to buy or rent.”53

Ministers played an active role in CFRE leadership. Not only were ministers members of the executive board, but also they were frequently asked to speak on racial and religious topics at CFRE monthly meetings. Examples of their meeting topics included: Rev. Aron Gilmartin, “Controversial Aspects of the New Bible;” Rabbi Martin Douglas, “Customs and Ceremonials in Jewish Religious Life;” and Rev. Robert N. Peters, “The March from Selma to Montgomery Alabama.”54 Specific church concerns were also CFRE meeting topics; examples were: “The Church Seeks the Answer to Seattle’s Intergroup Relations” and “What Should the Churches do in Answer to Seattle’s Intergroup Problems?”55

Using the meeting announcements from the Racial Equality Bulletin (1949 1968), the churches in which CFRE held meetings could be determined.56 These were the denominations that supported CFRE and that CFRE favored. (The number of churches was limited because CFRE tried to choose churches with a central location and bus access.) Baptist churches were clearly favored for meetings, followed by Congregational, Episcopal, and Methodist. These primary denominations had in common a history of social activism and several were active in missionary work that led to the incorporation of members from various races.57 The Congregational church was known for its commitment to the abolition of slavery and for civil rights. The Episcopal and Methodist churches were fairly liberal protestant denominations, active in both civil rights and humanitarian efforts. However, in keeping with their purpose of ending religious discrimination through social acquaintance, the Christian Friends also held meetings in churches of other faiths, though less frequently.

In addition to working with local churches on racial and religious issues, the Christian Friends collaborated with well‑known civil rights groups such as the Seattle branch of the NAACP, the Seattle Urban League and CORE, as well as with lesser known but locally active groups like the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle and the Washington State Anti‑Discrimination League. CFRE members who belonged to these and other organizations aided CFRE coordination with these other groups. The relationship became especially close when these “cross‑over” members served in active positions in each group.

In much the same way that ministers were appointed to the CFRE executive board, “[officials] from other organizations having kindred purposes” were chosen to sit on the CFRE board.58 This allowed the groups to keep in contact and to help each other with mutual projects. However, the greatest coordinator of these civil rights groups was the Seattle Civic Unity Committee (CUC).

Mayor William F. Devin appointed the Seattle Civic Unity Committee in February 1944. CFRE noted in its records that its letters to the mayor urging him to create a “City Interracial Committee” contributed to the formation of the CUC.59 Other contributing factors included the racial tension in the city and the wave of civic unity committees forming all over the country. The CUC recommended policies on racial matters to the mayor and city council, sought to combat racial tension through information and education, dealt with discrimination complaints and helped to coordinate the efforts of organizations working to eliminate intergroup tensions in Seattle.60 They organized these like‑minded groups through the Coordinating Council. Member groups included: the Urban League, Jackson Street Committee, NAACP, Race Relations Committee of the American Veterans’ Committee, Council of Social Agencies, CFRE, Council of Churches, Young Women’s Christian Association and the Student Adjustment Committee of the University of Washington.61 The CUC also put together conferences on race relations and organized speaking engagements.62

In addition to formal coordination, more intimate cooperation existed between CFRE and CUC. When CFRE’s office secretary was on vacation, CUC mimeographed hundreds of copies of the Racial Equality Bulletin for distribution and when CFRE’s typewriter was broken, the CUC loaned one to CFRE.63 When CUC was in a bind, CFRE office volunteers helped to address and post letters for their annual meeting.64 The support of each organization for the other is evidence of concern for one another and the belief that they were allies working toward the common cause of eliminating racial and religious discrimination and prejudice.

Mutual support between the NAACP and CFRE included the Christian Friends printing notices of NAACP meetings and membership drives in its publication, the Racial Equality Bulletin. Over the years, the relationship grew stronger. In 1964, CFRE was a contributing financial member of the NAACP and encouraged all of CFRE members to become members of the NAACP.65 When CFRE membership was in a state of decline and the group could no longer keep its office, the president of the Seattle NAACP, June Smith, offered to rent out space to CFRE in the NAACP office, an offer that the CFRE accepted in March of 1966.66 Collaboration included a picketing demonstration in front of the Woolworth and Kress stores, organized by the NAACP and supported by individual CFRE marchers. The demonstrators used the CFRE office as a resting place.67 Several of CFRE’s monthly meetings, like that of June 1960, “Work of the NAACP at the Present Time,” specifically concerned the NAACP.68 There was much cross-membership between the two organizations. Early CFRE sponsor Letcher Yarbrough was also the president of the Seattle NAACP and long‑time CFRE music committee chair, LeEtta S. King, was a representative of the Seattle NAACP to a national NAACP conference, an experience recorded in CFRE’s Racial Equality Bulletin.69

Though they publicized each other’s meetings and publications, CFRE did not have an extensive working relationship with the Seattle Urban League. Much of their relationship came through Lewis Watts who served for some time as the director and executive secretary of the Seattle Urban League and was a CFRE member. Watts spoke at several of CFRE’s monthly meetings, including that of March 1953 on the subject of how race relations had changed in Seattle over the previous decade.70

Though differing in method and membership profiles, the Congress of Racial Equality was nevertheless the organization most similar to CFRE. Both developed from a tradition of Christian social activism, both were founded in 1942 and focused on interracial concerns.71 In fact, the purposes of these groups were so similar that CFRE considered becoming an affiliate of CORE in 1945. However, the majority of CFRE members felt that they could not live up to the ideals of passive resistance upon which CORE was based.72 Though CFRE did not become a CORE affiliate, it did continue a strong relationship with CORE, especially after the Seattle chapter of CORE was established in July 1961. In addition to publicizing CORE’s meetings in the REB, CFRE worked with the national CORE to bring Rev. George Houser, national CORE chair, to Seattle in 1955.73 Members of CORE spoke at several CFRE meetings, among them was Ray Cooper, of the Seattle CORE chapter who described his participation in the Freedom Rides.74 In the nineteen‑sixties, CFRE and CORE cooperated in a number of boycotts that forced businesses to end their policy of hiring whites only.75

CFRE coordinated with other civil rights groups, though not as much as with the CUC, NAACP, CORE and the Urban League. These groups were promoted in the Racial Equality Bulletin, but did not share a close working relationships with CFRE. The Christian Friends maintained contact with the other groups through the Intergroup Agency Association facilitated by the Civic Unity Committee. Groups represented included the American Jewish Committee, the Anti‑Defamation League, CFRE, CUC, the Urban League, and the State Board Against Discrimination in Employment.76

Another form of contact was through the representatives of groups that were appointed to the CFRE executive board. Organizations that were represented on this board include the CUC, East Madison YMCA, Eastside YMCA, Family Life of Seattle Public Schools, the University of Washington Sociology Department and the Council of Churches.77 Glen Mansfield and Lonnie Shields served as liaisons for CFRE to the Washington State Anti-Discrimination League, the organization to which CFRE referred discrimination complaints.78

The Christian Friends for Racial Equality was an active organization in Seattle throughout the nineteen‑forties, fifties and sixties. University of Washington sociologists Ernest A. T. Barth and Baha Abu‑Laban conducted a study in 1959 of the African American community of Seattle. When participants were asked to list the most influential local organizations, the Christian Friends was ranked third behind the Seattle Urban League and the Seattle NAACP, respectively.79 Each sub‑community in Seattle would have ranked influential organizations differently, but with 1,000 members, in a city of 550,000 people, CFRE was an influential force in Seattle race relations.80

Though ending prejudice through social acquaintance was its primary objective, CFRE knew that it also had to combat discriminatory acts and policies of the government, businesses, property owners and even churches. CFRE attacked discrimination in several ways. One of these was through the CFRE letter club. Members wrote at least one letter a week to legislators, city council members and businesses.81 Some of the letters condemned discriminatory practices while trying to further the principle of a single humanity. Other letters congratulated businesses, churches and other organizations on their efforts to integrate, hire people of color and serve people of color. Additionally, letters were written in protest of the Amos and Andy television show, images of blacks as butlers in magazine ads and stereotyped roles in movies.82

Another approach used by CFRE to fight discrimination was to visit stores and restaurants and speak directly to the management about their practices. If CFRE investigated a claim of discrimination, in a restaurant, several members would be sent there in an interracial group. As charter member Bertha Pitts Campbell explained, “[that way we could] see if they discriminated and if they did, we had the white person as a witness.83 When approached in this manner, most restaurants offered equal service to both patrons, regardless of race. This method was also used to persuade businesses not to discriminate against Japanese Americans when they returned from internment camps in 1944.84 CFRE also used the tactic of personal interviews with doctors and hospital administration to urge them and the King County Medical Association to accept a policy of non‑discrimination.85

The Christian Friends took very seriously their role as community educators in regards to interracial and interfaith concerns. One facet of this was the speakers’ bureau of CFRE. Composed of a dozen dedicated and knowledgeable CFRE members, the speakers went to churches, youth groups, schools and other organizations to talk about interracial and interfaith matters and to facilitate discussions around those topics. In a typical two‑week span in February of 1952, bureau members spoke at eight engagements.86

The distribution of pamphlets also served to educate the community. Most pamphlets were not written by CFRE, but by authors and by organizations that were leaders in the field of race relations. However, CFRE did produce a pamphlet called “Do You Know” about the restrictions based on race in local cemeteries.87CFRE distributed pamphlets across the city, putting them in offices of doctors and dentists, in schools and in church lobbies.88 CFRE held a booth at Seafair and at the Evergreen State Fair to reach out to the community with educational pamphlets and with information from the volunteer staff.89

The Racial Equality Bulletin, published monthly by CFRE from May 1946 through the middle of 1968, was another great educational effort. In 1959, the REB was being mailed to sixteen states and Canada.90 The Bulletin was composed of meeting announcements for CFRE and other similar groups, national and international news items relating to race and religious relations that were taken from other sources and local news items from newspapers and CFRE’s own coverage. It was also partly a newsletter for the Christian Friends and thus it contained news of members, updates of the organization’s board meetings, descriptions of CFRE meetings, suggested reading lists and inspirational passages having to do with Christian faith, brotherhood and carrying out CFRE’s goals.

Each month the Bulletin was constructed by a five person Editorial Committee, who mimeographed (later copied), hand‑addressed and posted it to around 500 subscribers. Readers were asked to submit comments, suggestions and articles for publication in the Bulletin.91 In addition to individual subscribers, the University of Washington, Seattle Public Schools and the Seattle Public Libraries subscribed to the Racial Equality Bulletin. CFRE traded subscriptions with like‑minded groups such as the Friendship House in Chicago who printed the newsletter Community and the Community Relations Conference of Southern California who printed The Community Reporter.92 It is easy to see how the Racial Equality Bulletin reached so many readers and was able to serve as both a news source and a vehicle of exchange for CFRE ideas and information.

The meetings of the Christian Friends were another important form of community education. Notices were sent to local newspapers announcing the meetings and cooperating churches also announced the meetings and their topics.93 Members of the host church usually attended the meetings even if they were not CFRE members and CFRE members were encouraged to bring friends to the meetings to expose them to the CFRE mission. In this way, CFRE sought to inform people outside of the CFRE network about interracial and interfaith concerns. These meetings involved dynamic speakers and community leaders; some were CFRE members. Notable speakers included: Glen Mansfield, Executive Secretary of the Washington State Board Against Discrimination; Lewis Watts, Director of the Seattle Urban League; George Houser, Executive Director of the national CORE; Mark A. Smith, Administrator of Fair Employment Practices Division (Oregon), and President of Portland Urban League; Robert Brooks, Executive Secretary of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU); and Wing Luke, Seattle City Councilman.94

The final form of community education was performed through the individual acts of CFRE members. This was the social acquaintance emphasis of the Christian Friends. CFRE believed that social acquaintance and interaction by members of different races and faiths would lead to human understanding and was the only way to eliminate prejudice. The Christian Friends looked upon groups like the NAACP as trying to legislate against discrimination, but CFRE wanted to stop discrimination at its source: individual prejudice. Because of this belief, CFRE engaged in relatively few legal and coercive means to end discrimination.95

CFRE practiced positive social interaction in two ways: one was during the social hour of CFRE meetings and the other was through members’ daily interactions with people. Articles in the Racial Equality Bulletin taught members how to respond to prejudiced remarks and how to demonstrate the principle of brotherhood.96CFRE meetings were even devoted to this topic and role‑play helped members feel confident in handling the situation.97 When engaged in conversations with someone who had made a prejudiced statement, CFRE members were taught never to be on the defensive and always to be polite in explaining the errors of prejudice. In the forties, several clauses were added to CFRE’s Statement of Purpose to emphasize the importance of social contact. This form of community outreach was responsible for touching many Seattleites who may have otherwise never been concerned with interracial and interfaith concerns.

Admittedly, the Christian Friends’ forum for social acquaintance was “artificial.” Nevertheless, CFRE believed that despite the artificial organization of potlucks, picnics, plays, teas, parties, square dances and luncheons, that the fellowship that developed was real.98 Though at first glance the Christian Friends appear to be affected, the sincerity and care for race relations and each other in their circle of “friends” comes through in their writings and in their volunteer work.

An organized form of education and social acquaintance was the interracial, interfaith home visit program that originated in Cleveland and Chicago in the early sixties and was adopted by the Christian Friends in 1964. Another Seattle group, the New Year Callers had an annual activity similar to the interracial, interfaith home visit day and many CFRE members had participated in the New Year Callers events.99 In the interracial, interfaith home visit program, families volunteered to be callers or hosts. They were then paired with a family of a different race or religion for a visit that usually involved light refreshments and a discussion, sometimes with a topic and other times with no prescribed subject.100 The program was adopted by CFRE because, as CFRE president Reverend Robert B. Shaw said, “it [took] the surest method of combating prejudice personal encounter with members of another race or faith.”101 The home visit program grew from 75 participants in February of 1964 to 500 participants in the April 1965 Home Visit Day.102 By April 1965, the Catholic Interracial Council, Temple De Hirsch and the Christian Family Movement had joined CFRE in co‑sponsoring the event.103 Yet after these three home visit days in Seattle, the program was assessed as being ineffectual. This was because home visit participants were those who were already unprejudiced; the program couldn’t influence the prejudiced to rethink their attitudes because it could never induce prejudiced people to participate.104

CFRE was involved in many projects to end discrimination in Seattle but there are two key undertakings that highlight Christian Friends activism: ending racial and religious cemetery restrictions and working for fair housing and neighborhood integration. These two projects spanned many years and involved massive amounts of research and community education. It was for these projects that CFRE had to enlist the cooperation of other civil rights organizations in order to mobilize the community to support these issues. After much hard work and some disappointment, racial restrictions were removed from Seattle cemeteries, restrictive covenants were deemed legally unenforceable and the process of neighborhood integration was started.

CFRE’s interest in cemetery discrimination began in 1945 after it had learned the disheartening stories of an African American woman who was not allowed to purchase a plot in the same cemetery as her white mother and of a Japanese American friend of CFRE who was prohibited from purchasing a burial plot for his father because of his race.105 That year the Christian Friends conducted a survey to determine which cemeteries had restrictions based on race. For several years, CFRE continued to alert the community to the discriminatory restrictions of cemeteries while it tried to organize support for the ending of these restrictive policies. By 1948, churches supporting CFRE had circulated petitions signed by 1100 people who favored ending the restrictive policies of cemeteries.106 Several ministerial associations also spoke against the policies and wrote letters to cemeteries stating their positions. The Puget Sound Ministers’ Association went on record denouncing restrictive covenants and segregation in cemeteries as “unchristian, uncivilized and unintelligent.”107 The Shelley vs. Kramer Supreme Court decision in 1948 deemed restrictive covenants legally unenforceable; CFRE argued this decision applied to cemetery policies.108

After the Supreme Court decision, CFRE mobilized to enlist the support of other organizations against restrictions in cemetery policies. Groups and churches that allied with CFRE included the Puget Sound Association of Congregational Ministers, the Seattle Baptist Ministers and Missionaries, University Unitarian Church, Green Lake Congregational Church, Methodist State Federation for Social Action, Church of the People, Methodist Ministerial Association, Social Action Committee of the University Congregational Church, First Baptist Church and Seattle Presbyterian Church.109

The Christian Friends also worked to garner community support for ending cemetery restrictions. By 1949 CFRE had printed and distributed pamphlets, written by CFRE member Ethelyn Hartwich, which stated the policies of local cemeteries.110 The Civic Unity Committee had now joined the movement to end the restrictive policies and held private meetings with the cemetery owners to discuss their policies.111 Community support to end the policies continued to grow and by 1951 the issue became highly visible when the Seattle Times carried four articles about cemetery policies written by Byron Fish. Despite CFRE’s intention to stay away from legal battles, it had scheduled meetings with the Assistant to the State Attorney General to discuss cemetery policies.112

In February of 1953, the Washington State Legislature passed a set of laws that regulated cemetery operation. Among the regulations was the statement: “It shall be unlawful for any cemetery under this act to refuse burial to any person because such person may not be of the Caucasian race.”113 The passage of this statute concluded the work of the Christian Friends to end racial cemetery restrictions. Knowing that this was a small victory, CFRE vowed that there was more work to be done to wipe out discrimination and to end prejudice.114

One of the very first civil rights groups to bring attention to housing, the Christian Friends’ work to end restrictive covenants began in early 1944. CFRE volunteers went to the county‑city building to collect deeds bearing restrictive covenants. By late spring of 1944, CFRE had sent a letter, endorsed by civic and church leaders, to pastors quoting the Broadmoor Covenant and asking for their support towards ending restrictive covenants.115 This restrictive covenant of a 23rd Avenue house, written into the contract in 1938, was a typical example of a restrictive covenant:

The purchaser must be of the white or Caucasian race and… the property is not to be sold, encumbered, conveyed, leased or rented to any person who is not of the white or Caucasian race. In the event of the violation of this covenant the title to the property shall revert to the [name deleted] estate. This is also binding on the heirs, administration, successors and assigns of the purchaser.116

Over the next several years, CFRE collected sixty‑four covenants (a fraction of the total number of restrictive covenants) and compiled them into an educational leaflet for community distribution. CFRE wrote to the Seattle Realtors’ Association to express its “uncompromising disapproval of racial and religious restrictions in property deeds.”117 Letters were also sent to legislators urging them to end segregation and racial restrictions in federal housing.

Locally, CFRE had been successful in raising awareness of restrictive covenants. In the spring of 1946, an African American attempted to buy a house in the Rainier District. The residents of the district tried to create a restrictive covenant barring the sale of homes in their neighborhood to people of color. When CFRE heard of this, it alerted the community to the planned covenant. Enough community members were against the covenant that it failed and the African American was able to purchase the home.118

Letters continued to be posted to citizens, legislators, churches, businesses and organizations stating CFRE’s disapproval of restrictive covenants and encouraging support towards ending the covenants.119 By 1947 the leaflet containing the sixty‑four covenants was finished. Two‑hundred‑and‑fifty copies of the fourteen page brochure were mimeographed and distributed.120

With the Shelley vs. Kramer Supreme Court decision of 1948 declaring restrictive covenants unenforceable, CFRE now turned its attention to neighborhood integration, believing that church and school integration would result from integrated neighborhoods. CFRE also believed that Christians, being a large portion of Seattle’s population had the power to determine community attitudes; their cooperation towards integrated housing would lead to integrated neighborhoods.121 CFRE tried to create a listing service for buyers of color that matched them with sellers who were from predominantly white neighborhoods. Pastors were asked to enlist willing members of their congregation to participate in this matching service and to create a church environment that was favorable to integration.122The Civic Unity Committee eventually adopted the work of matching buyers and sellers, while CFRE stayed active in recruiting names for the lists.123 Despite good intentions and a fair amount of listings, this service did not achieve much success.124 Of four listed houses in white neighborhoods that were open for sale to people of color in 1955, no buyers of color could be found.125 CFRE did not try to determine why no people of color volunteered to buy these houses.

CFRE recognized that much of the resistance by homeowners and their neighbors to sell to people of color was due to the fear of lowered property values resulting from a person of color moved into the neighborhood. Consequently, CFRE sought to educate homeowners to dispel this myth. The educational effort went hand‑in‑hand with their push to integrate neighborhoods.126Another part of this plan was to encourage supporters of open housing who saw “for sale” signs in their neighborhood to talk with the seller and let the seller know that new neighbors were welcomed regardless of race, creed or national origin.127

In April of 1958, CFRE tried a new tactic to foster integration, asking the Seattle City Council to ban racial and religious restrictions in housing.128 At the same time, CFRE was working towards generating a public statement by Seattle homeowners that was in favor of integrated neighborhoods.129 CFRE supported the Open Housing Pledge constructed by the Committee to Promote Open Housing. The group gathered 1600 pledges affirming the belief in open housing and the welcoming of neighbors regardless of race, creed, or national origin.130 A 1962 survey by the Seattle American Friends Service Committee revealed that open housing was favored by 50% of the respondents, yet the state legislature had not yet passed a fair housing bill.131

In 1962, CFRE tried a new method: to motivate whites to move into the Central District. In an article written for the Racial Equality Bulletin, CFRE outlined the advantages of the Central District: wholesomeness from living with people of different races and religions, convenience, views, integrated schools and well‑kept houses.132

In the legislative session of 1963, fair housing bills were introduced for consideration at the request of the Governor, Seattle’s Mayor and the Seattle City Council. CFRE and their allies supported the bills, encouraging voters to contact legislators in favor of the bills.133 A five day, non‑stop vigil was organized at the Capitol in support of the bills that had not come out of committee for over a month.134 However, both bills were killed in the Rules Committee in 1963, just as in 1959 and 1961.135 The open housing ordinance on the October 10”, 1964 Seattle ballot was also defeated.136

In an attempt to vote into office legislators who supported civil rights and open housing, CFRE’s September 1964 meeting was a “Candidates’ Forum on Civil Rights.” The forum had potential to be widely attended, however only seventy people and a handful of candidates came.137 CFRE was by now losing much of its influence while groups with legislative and demonstrative agendas were gaining membership. Fair housing legislation again died in committee in the 1965 session.138

In June of 1965, the Seattle Real Estate Board announced, on its own, a policy of non‑discrimination. This policy followed the Washington State Board of Realtors voluntary code.139 At last, in 1968, the Seattle City Council passed an open housing policy.140The unanimous passage of this policy was remarkable given the rocky history of open housing in Seattle but the decision came twenty years after restrictive covenants had been declared legally unenforceable. In this case, Seattle had lost its status as a civil rights leader. The measure came after voluntary integration had already made in‑roads against segregation.

CFRE’s work to end cemetery restrictions seems somewhat unimportant in the larger scheme of civil rights work and CFRE’s methods for creating neighborhood integration seem to lose effectiveness over time. True, CFRE’s efforts helped to end racial restrictions in cemeteries and housing, but what about all of the other issues at hand like achieving equality in employment, education and personal treatment? Did CFRE shy away from these larger issues because they were not up to the fight or did they believe that other groups could work more effectively on these issues because of their legal and direct action methods? The work of the Christian Friends towards integrating Seattle’s neighborhoods shows that CFRE was not wholly removed from the larger civil rights picture, but CFRE’s drive to end segregation could only go as far as their social methods would allow. Over time, the radical methods CFRE employed in 1942 became less and less radical and gradually lost effectiveness until by the sixties when legal and direct action strategies were crucial to ending discrimination, CFRE was practically impotent. Nevertheless, CFRE continued to see its educational, social and religious approach as a special part of the larger civil rights picture, which was “linked at the fringes” with the other civil rights groups’ specific objectives.141Because it was different, CFRE reasoned that its approach was necessary to the civil rights movement.

The legislative tactics CFRE chose to try to end cemetery and housing restrictions and to foster neighborhood integration are at odds with its stated belief that “though you can legislate against discrimination, you can cure prejudice only by social acquaintance.”142 However, this belief did not deny the effectiveness of legislative techniques or their necessity in certain areas. CFRE’s increased focus on legislative issues as time progressed shows that the Christian Friends tried to respond to the new civil rights climate that emerged during the late fifties and throughout the sixties, a climate that was increasingly concerned with legal and direct action techniques. CFRE was not more active in lobbying earlier because that is not what the civil rights climate called for; there were few civil rights bills to lobby for until the mid‑fifties. The legislation of the fifties and sixties was the product of the education and community activism of groups like CFRE during the forties. As this legislation arose, CFRE had to adapt its group to a more legislative tone if it was to have any place in the changing civil rights climate.

Though the Christian Friends tried to adapt and find its role in the new civil rights climate of the sixties, this was extremely difficult for the group. By early spring 1966, the Christian Friends was in a state of crisis. The treasury was drained, the board was faced with being “almost entirely unable to persuade members to accept responsibilities such as running committees or even being on them” and the organization was functioning without a president because no one was willing to serve.143 A meeting was held at Mt. Zion Baptist Church to determine if CFRE should continue and if so, in what capacity. How had such a prominent and successful organization become so weak? This change had not happened suddenly; CFRE had been dealing with funding concerns and identity issues for nearly fifteen years.

In the spring of 1953, Christian Friends for Racial Equality members began to question the appropriateness of “racial equality” in the CFRE name. One argument against “racial equality” was that the Christian Friends work for more than just racial equality. Others felt that CFRE’s long name was cumbersome and limited their publicity in newspapers. However, after reviewing the issues, the committee examining the issue decided that Christian Friends for Racial Equality, though lengthy, was a name recognized by the public for its good works and though the purpose of the group may have shifted since its formation in 1942, the name should remain unchanged.144

It was during this same time period (1952‑1953), that CFRE started to notice a decline in social gatherings, though attendance at meetings was high.145 This phenomenon is part of a shift in the function of CFRE away from small social acquaintance activities and towards more educational pursuits and community activism work. Evidence of the shift included the new endeavors of CFRE to hold booths at the Evergreen State Fair and at Seafair, to lobby for civil rights legislation in Olympia and to educate the public on the civil rights legislation after it had been passed. Though small social gatherings virtually ended during this period, the large social events, like the CFRE Annual Fun Fest, Annual Dinner Meeting and the Annual Picnic continued to increase in attendance.146 The shift is the product of an increasing membership that could not sustain an intimate atmosphere. CFRE had to shift its endeavors to match its membership. However, because the original niche of CFRE had been social acquaintance and friendship, this shift would ultimately return to trouble the organization in the form of identity and purpose confusion.

In the April 1959 Racial Equality Bulletin, the article entitled, “Look! I Haven’t Seen You for a Couple of Years!,” remarked, “we used to stand around the coffee table and talk… you could hear delighted laughter and the making of dates for lunch, or a sing in somebody’s home, or maybe a leisurely evening with a game.”147The article urged members to stop being “too busy and important” to attend the meetings. This plea for the good old days when the Christian Friends used to be pals and attend meetings because of the pleasure, not the duty, signifies that CFRE was losing appeal. People weren’t coming for either the educational meetings or the social aspects; this article was a call to recapture the original attraction of the Christian Friends. The article continued, “Those were the days when no one ever thought of the Christian Friends’ treasury being without money!”148 Hand in hand with a drop in membership and attendance was the loss of funds, a problem that would later reach desperate proportions.

By 1962, CFRE was re‑examining its purpose in board meetings. Questions posed at the February 1962 board meeting included: “Where is the CFRE going? What exactly are our goals? Can we do our best work through the churches?”149 These questions illustrate that CFRE was no longer confidant in its basic purpose, direction and work in Seattle churches. In order to reach a point where such deep introspection takes place, CFRE must have felt that its original objectives and goals were not working as they had wished. However, after the February meeting, CFRE reported a “renewed interest and faith in our accomplishments for the future.”150 Unfortunately, the direction that was chosen for CFRE’s future was not published in the Bulletin, but the subsequent actions of CFRE indicate that the group progressed much like it had before.

Decreased contributions and financial troubles led to the dispensing of the paid secretarial position in August of 1963. Yet even though funds were low, membership and volunteer help was enough to be able to staff the office regularly with volunteers.151CFRE’s financial trouble had become so great that at the January 1964 CFRE meeting, members voted unanimously that henceforth membership would be on a dues‑paying basis. There were several levels of membership to fit different budgets, but the original inclusive purpose of a non‑dues organization, whose membership was based solely on the belief in CFRE’s Statement of Purpose was lost.152

CFRE president Reverend Robert B. Shaw wrote “An Urgent Call to Action by the New CFRE President,” for the January 1964 Racial Equality Bulletin. In this piece, he noted that what was once bold action taken by CFRE in the early forties was now taken for granted. He wanted the Christian Friends to once again adopt an innovative an bold race relations program. At the same time, he still believed that CFRE’s best work was through the social acquaintance method. Thus, he proposed the interracial, interfaith home visitation project as a way to “produce more interest in [CFRE] meetings and enlarge the number attending.” He envisioned that home visits could revitalize CFRE and possibly lead to “a whole range of new activities in the general field of bringing people together, whether for serious or recreational purposes.”153

Though three successful home visit days were organized, it was not enough to restore CFRE membership and revitalize the organization. In the President’s Report of 1965, Shaw reported that the future of home visits was uncertain and CFRE would probably not sponsor any more. He noted that attendance was meager at meetings and “small gatherings resulted in a loss of interracial character [that] detracted from the purpose” (though he did not state in what manner). He also cited problems in finding volunteers for committee work, which was a large problem because the goal of CFRE was to have all members be “crew members and not just passengers.” Finally, he emphasized the difficult task of the CFRE board to re-examine its role in Seattle race relations, noting that it is possible that “the racial equality struggle here has gone beyond the present [CFRE] Statement of Purpose.”154

At the January 1966 board meeting, it was decided to put the continuation of CFRE up to a vote at the March 16 meeting.155 A February potluck let members meet to discuss both sides of the issue. Many felt that CFRE had been a pioneer in Seattle race relations for almost 25 years, but that now other organizations were doing the same work Edith Steinmetz, CFRE founder, announced that she would accept either decision equally.156 The March 7th letter mailed by Alice B. Nugent, on behalf of the CFRE board, stated the arguments for both the dissolution of CFRE and for the continuation of CFRE in a modified form.157 Both sides were presented at the March 13, 1966 meeting that had a surprisingly small number of attendees. It was unanimously decided to give up the CFRE office. Twelve members voted to disband the Christian Friends and fourteen voted to continue CFRE and to accept the offer of NAACP president June Smith to provide CFRE with desk space at the NAACP office. After the decision was made to continue CFRE, Joan Hiltner and Ross Burks signed up to coordinate the organization while fourteen others signed up for committee work.158 In May, the new CFRE program coordinators and several board members met and agreed to continue to operate CFRE under the original constitution and by‑laws; membership dues were eliminated. Eight members of the board agreed to continue to serve and five declined.159

The Christian Friends had chosen to continue with their original principles of education and social interaction despite a completely different civil rights climate in 1966 than in 1942. Once again a small group of about thirty members, CFRE was free to engage in the social acquaintance environment of old. Small gatherings and picnics were the norm. Educational meetings were organized in conjunction with other civil rights groups and events were supported by CFRE, but organized by other groups. CFRE did continue the Annual Picnic, Annual Membership Dinner and the Annual February Potluck Dinner. The Racial Equality Bulletin was retired sometime in late 1968 and replaced by a small newsletter.160

During the years after CFRE’s re‑birth, the Christian Friends sought to regain a place in the new civil rights struggle. CFRE envisioned the revival of home visits, they wanted to increase scholarship money for African American students and wanted to assist with finding homes for infants of color by supporting the Medina Children’s Service that had the backing of Edith Steinmetz.161

CFRE also dealt with the changing civil rights climate by holding meetings that addressed the issue of a new black militancy. At CFRE’s twenty‑fourth annual dinner meeting in May 1966, the primary speaker was Carl Miller, the president of the Seattle Chapter of the Student Non‑Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). His speech was entitled, “Black Militancy, One Side of the Coin.” In the December 1966 Racial Equality Bulletin CFRE again tried to formulate its assessment of Black Power.162 The REB carried the Southern Patriot article “Anatomy of a Black Panther: What They’re Saying in Loundes County, Alabama.” In this article, the black panther was portrayed as a symbol fighting, “not with fists, but… for power” and Black Power was defined as “not to take over, but to share.” This article presented CFRE members with a positive, mostly non‑threatening image of Black Power ideology and the new direction of civil rights. By this time, the civil rights struggle and ideology was very much beyond simple social acquaintance and integration Therefore, in order for CFRE to be effective in the civil rights climate of the late sixties and early seventies, it would have had to practice direct action, not just accept it as legitimate for others.

Throughout 1970, the last year of CFRE records, the group had planned social and educational meetings as well as the annual potluck and the annual dinner meeting.163 It is most probably the case that CFRE records disappeared because the person whose sources were used discontinued membership and not because CFRE disbanded. In any case, the exact end of the Christian Friends is unknown.

Charting the identity crisis of CFRE from 1952 through 1966 and even into 1970, it can be seen that the Christian Friends was trying to find its place amidst an ever-changing civil rights climate. When the civil rights struggle began to be more publicized in the mid‑fifties, CFRE noted a decline in the attendance of social gatherings, but an increase in attendance at educational sessions. Though it had earlier sworn off legal methods, by the mid‑fifties, CFRE advocated legal action to end cemetery discrimination and housing restrictions, CFRE’s legal action coincides with the time when legal means towards ending discrimination began to be increasingly successful and necessary in the Civil Rights Movement. Nevertheless, CFRE could not adjust itself to the direct action methods demanded by the civil rights struggle in the late‑fifties and sixties, even though this method was recognized by CFRE as being the only way that “prejudices and practices obstructing racial equality [could] be effectively brought to the attention of those engaging in, or responsible for, segregation and discrimination.”164

Despite the fact that CFRE methods remained largely the same throughout its lifespan, its place in the civil rights struggle changed because CFRE did not evolve its practices in accordance to the evolving struggle. The once pioneering social interaction and educational plan of CFRE that first brought attention to the housing concerns of the colored people of Seattle had become ineffectual as the civil rights struggle moved towards ending legal and de‑facto segregation through direct action demonstrations and legal challenges. In 1964, CFRE President Rev. Robert B. Shaw wrote that CFRE was once a pioneer in Seattle race relations because a program of “interracial communication… was quite remarkable.” However, he continued, “today [interracial communication] is taken for granted. What was bold twenty years ago is widely accepted today.” He urged CFRE to again be a pioneer in race relations by adopting a demonstrative strategy, but CFRE membership was not ready to change its methods.165

Though CFRE found it difficult to adjust to the changing civil rights climate, it did impact Seattle race relations, especially during the earlier part of its organization. The exact nature of this impact is difficult to judge because CFRE rarely left evaluative records of its programs and because other civil rights groups were also working on many of the same issues as the Christian Friends. Much of CFRE work during the latter half of its organization seemed to create more of an ameliorative effect rather than that leading to a direct social change.

It is possible to estimate CFRE’s impact by examining the movements started by the group and the people who the group influenced. The Christian Friends was among the very first to begin to work for fair housing in Seattle, bringing this issue to the attention of the general public as early as 1944, twenty‑four years before fair‑housing legislation was passed in Washington. The work of CFRE on housing influenced and encouraged many other groups to join them in the effort. CFRE was also a pioneer in ending cemetery restrictions, beginning this work in 1945. CFRE foresight and motivation contributed to the creation of Seattle’s Civic Unity Committee, a very effective public organ that worked to improve civil rights.

In another manner, CFRE impacted the community through the actions of its members. CFRE members strove to create a positive environment for interracial and inter‑religious exchange by talking with their neighbors and co‑workers. Many CFRE members also held positions of community influence. These members could have integrated the CFRE philosophy into their own influential statements and thus extended CFRE influence further.

Ironically, one area that the Christian Friends was most likely unable to be influential in was the ending of prejudice in individuals. Though this was the primary objective of CFRE, to be accomplished through social interaction, most of the people who came to CFRE meetings and participated in CFRE educational programs were already convinced that all people were created equal and should be treated as such. CFRE could not directly influence prejudiced minds because these people tended to stay away from the Christian Friends. This was the major problem associated with the interracial home visit program. Reverend Robert B. Shaw notes the limitations of the program as being: “many participants were already unprejudiced and too few new people participated.”166 This dilemma seemed to be the case with many CFRE programs.

The Christian Friends for Racial Equality is an interesting organization to study because of its membership and because of its pioneering work in Seattle race and religious relations. Civil rights groups composed of two‑thirds women are very rare. Though women have been active in many social welfare causes throughout the civil rights movement, they have seldom enjoyed the leadership positions and credit that should accompany their dedication. In the Christian Friends, women served in 72% of the leadership positions and represented CFRE to the community. Seattle’s acceptance of the predominately female civil rights group helped to create an environment for female participation in Seattle’s social justice groups of the seventies and on into the future.

Founded in 1942, the group enjoyed ten years as a pioneer in Seattle race relations, introducing the concern of restrictive covenants to Seattle’s civil rights struggle and motivating Seattle’s churches to become community leaders fighting for integration and equality. Though CFRE adopted some legal means of fighting discrimination, the groups’ insistence to continue to focus on social interaction as the primary method to ending prejudice limited their impact and influence as the Civil Rights Movement shifted towards direct action and legal challenges. As a result of their resistance to change, the Christian Friends went from being Seattle’s largest interracial organization in the mid-fifties to a group of fourteen members who voted to continue the organization in March 1966. Despite the ineffectiveness that encompassed the organization during its latter years, the Christian Friends must be remembered and recognized for its early contributions to Seattle race and religious relations, primarily in the area of housing, but also in community education. Groups such as the Christian Friends should be acknowledged as the necessary forerunners to the legal and direct action organizations of the late‑fifties and sixties. The Christian Friends helped to lay the foundation for later change through their work in community education and by working with the local government, churches and the business community to make positive race and religious relations a community priority.

Copyright © Johanna Phillips 2006

1 CFRE used the term ‘intergroup’ to refer to the combination of people from various racial, religious, and national backgrounds. I will use the term in the same way it was employed by CFRE.

2 Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 throught the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994) 154-156.

3 Carlos A. Schwantes, The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996) 413.

4 Esther Hall Mumford, Seven Stars and Orion: Reflections of the Past, (Seattle: Ananse Press, 1986) 14-15.

5 Taylor 172.

6 Taylor 173.

7 Taylor 173.

8 Robert O’Brien, “Profiles: Seattle,” Journal of Educational Sociology, 19 (1945): 152.

9 Stuart C. Dodd and Robert W. O’Brien, “Racial Attitude Survey as a Basis for Community Planning: The Broadview (Seattle) Study,” Journal of Educational Sociology, 23 (1949): 118-119.

10 O’Brien, “Profiles: Seattle,” 154-155.

11 Christian Friends for Racial Equality (CFRE) records, University of Washington Libraries, Unaccessioned, “Twenty Years History of the Christian Friends for Racial Equality,” p. 1.

12 CFRE, Unaccessioned, “Twenty Years History,” 2.

13 CFRE, Unaccessioned, “Twenty Years History,” 2.

14 CFRE, Unaccessioned, “Twenty Years History,” 3.

15 Christian Friends for Racial Equality records, University of Washington Libraries, Unaccessioned, hand-written list by Mrs. Steinmetz.

16 CFRE, Unaccessioned, “Twenty Years History,” 3.