“In the present world crisis, brotherhood is not optional.”

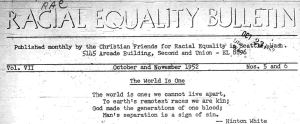

-Racial Equality Bulletin, February, 1952

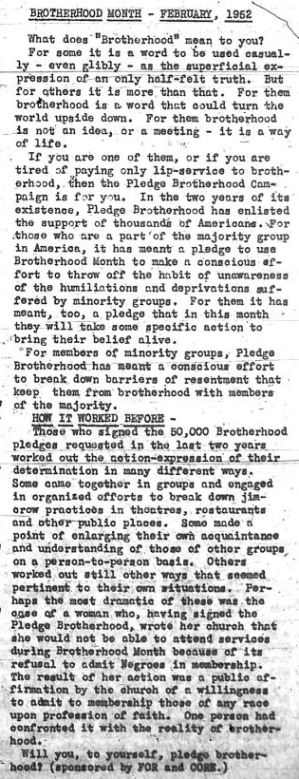

The quotation above summarizes the basic philosophy behind the creation of the Racial Equality Bulletin. Published by the Christian Friends for Racial Equality (CFRE), the paper asserted that brotherhood, or the coming together of people, was integral to the fight against racism. The articles and the community events organized by the Racial Equality Bulletin reveal that the CFRE believed that racism and discrimination could be overcome through love, education, and a better understanding of other cultures. The paper not only delivered news on the national civil rights movement, but also served as a social events resource, helping to coordinate numerous activities and events, from square dancing to educational forums on the Jewish faith and interracial picnics. It also strove to be inclusive by recognizing the accomplishments of people from various ethnic backgrounds from around the Seattle community. Central to all of this was the influence of the Christian faith, which was pervasive throughout the paper. In fact, the opening line of the Bulletin’s statement of purpose referred to the religious motivation behind the group’s involvement in the fight for racial equality:

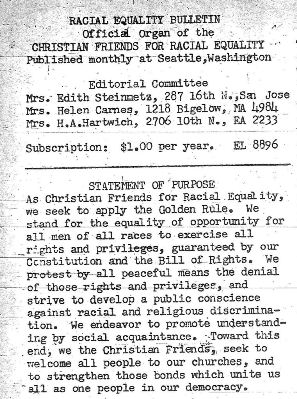

“As Christian Friends for Racial Equality, we seek to apply the Golden Rule. We stand for the equality of opportunity for all men of all races to exercise all rights and privileges, guaranteed by our Constitution and Bill of Rights. We protest by peaceful means the denial of those rights and privileges, and strive to develop a public conscience against racial and religious discrimination. We endeavor to promote understanding by social acquaintance…”

The CFRE was formed in May of 1942 in the Seattle area. The original group consisted of seventeen people from seven different Christian denominations and the Jewish faith. The group was multi-racial and was primarily made up of women, who made up two-thirds of the membership and three-fourths of the officers 1. There were four editors of the newspaper – three women and one man – as well as volunteers to do secretarial work in the office. A yearly subscription to the paper was $1.00. The membership of the CFRE was 500 strong in 1947, suggesting that the paper had a sizeable readership and was financially secure 2.

CFRE meetings were held monthly in different churches around Seattle, including the Episcopal, Baptist, Congregational, and Unitarian. The Bulletin advertised the date, time, and location of these meetings. The meetings were used as educational opportunities, as well as to discuss the issues of the group and the newspaper. For example, during a meeting in February of 1952, a CFRE member gave a presentation on the topic of Hiroshima. Other meetings discussed local issues like Native American rights and discrimination. At the November 18, 1952 meeting, the CFRE hosted Dr. Viola Garfield of the University of Washington for a lecture titled, “The Northwest Indian Today.” During the group’s January 1953 meeting, Mr. Robert Jones discussed “The Citizen’s Responsibility for Anti-Discrimination Legislation.” At one unique meeting in November of 1951, the CFRE discussed racist behavior in the community and trained members how to respond to racially offensive statements. The training session was advertised in the previous month’s edition of the Racial Equality Bulletin:

“Wops never could learn decent manners.” Have you ever been present when remarks like this have been made in public…have you thought that you really should say something in rebuttal, but have not known what to say…? Well, at our November meeting we’re going to dig into this problem of what to say and how to say it, and why it’s important to say something.”

The group felt the training was so necessary that they even role-played some of the various situations, and the topic was apparently popular enough that they extended the discussion and training into the following month.

One of the primary goals of the Racial Equality Bulletin was to educate readers about events occurring in other parts of the nation and around the world. For example, the Bulletin frequently reported on segregation in the American South. In September 1951, an article headlined “Separate But Not So Equal” discussed the inequalities in segregated Southern public schools, citing the inadequate funding provided for African-American schools. In the November 1951 issue, the paper highlighted the racist immigration policies of Australia, where customs officials would not allow a Japanese-American to pass into the country. The Bulletin concentrated on the successes of the civil rights movement far more than on the struggles. For example, the December 1951 issue contained seven articles that could be categorized as positive achievements of the movement, including one about universities that had pledged to desegregate and another about a city mayor who had banned restrictive housing covenants. Meanwhile, in the same issue only two articles discussed negative aspects of the ongoing struggle.

The Christian Friends for Racial Equality also educated members about other cultures, and used the Racial Equality Bulletin to publicize its cultural events. For example, in October of 1951 the Bulletin encouraged readers to join a Mr. and Mrs. Hayes in their home to discuss Jewish holidays that were going to be observed during that month. And on August 19, 1952, the Bulletin informed readers that the CFRE was hosting a cooking demonstration of Korean and Scandinavian food at its monthly meeting.

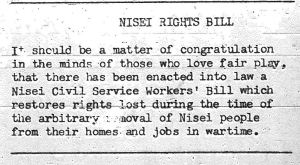

In the spirit of brotherhood, the Bulletin documented the struggles and celebrated the victories of many ethnic groups, including African-Americans, Japanese, and Native-Americans. An article headlined “The Real Problem” in the December 1951 issue examined the poverty of residents of the Navaho Reservation. Meanwhile, the October 1952 issue celebrated the passage of a “Nisei Rights Bill” for the Japanese-American community:

“It should be a matter of congratulation…that there has been enacted into law a Nisei Civil Service Workers’ Bill which restores rights lost during the time of arbitrary removal of Nisei people from the home and jobs during wartime.”

Another example of the paper’s support for the Japanese-American community, and for people of color in general, was when it recognized the achievement of a second generation Japanese girl who won the Oregon state beauty contest (July, 1952).

Along with education, one of the primary beliefs of the Christian Friends for Racial Equality was that social interaction was a necessary part of breaking down racial boundaries. The staff of the CFRE proudly differentiated itself from other civil rights organizations because of its emphasis on organizing social gatherings, including picnics, square dancing, and nights out to the theatre. In the December 1952 issue of the Bulletin, the article “Do We Overlap” discussed this point. The article was written in response to questions from community members about how the various civil rights organizations differed from each other. The article named the different organizations and explained the importance of each. After emphasizing the similarities in the organizations’ struggles for racial equality, the Bulletin argued that the Christian Friends for Racial Equality was different from other groups on the basis of its belief in social networking to bring about brotherhood:

“[The CFRE’s] social program is based on the idea that, tho you can legislate against discrimination, you can cure prejudice only by social acquaintance, by the actual friendly association of people in congenial gatherings.”

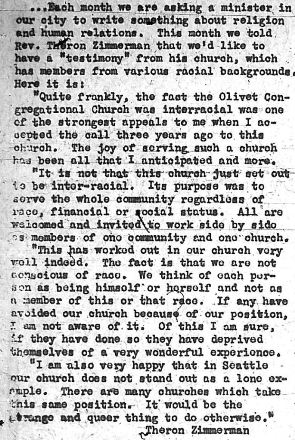

Of course, the idea of brotherhood through social interaction could only be realized if the people reading the Bulletin and attending the social activities put on by the CFRE were of varying ethnicities. There is reason to believe that this was the case. First of all, the CFRE was founded by an interracial group of Caucasian and African-American women3. The fact that CFRE meetings were held in different churches throughout the Seattle area also signifies an effort to get people of varying faiths and ethnic backgrounds involved. One way the Racial Equality Bulletin helped to accomplish this was by having ministers from different churches in the Seattle area contribute an article every month about the connection between Christianity and promoting racial equality. In the December 1951 issue, Reverend Harold Jensen, the Caucasian pastor of First Baptist Church, was the contributing minister. He discussed his application of religion to race relations by describing a Christmas when he was visiting an African-American church and was startled to see a Black Christ-Child. “It startled me and humbled me,” Jenson wrote. “I knew it was right and that I really should not have been startled at all.” He went on to discuss how the brotherhood of man and Christ’s love for all bound him to believe that the fight for racial equality was a fight that Christians should be a part of. Surely, much of Reverend Jenson’s congregation was white and one would suspect that there was plenty of support for the CFRE. There is evidence to suggest the involvement of African-Americans in the group, as well. Many of the articles in the Racial Equality Bulletin referred to racism and discrimination against African-Americans. For example, all of the school segregation articles from 1951-1953 dealt with either the success of new African American enrollment or new information about a university that was still refusing to admit African-Americans. One can assume African-Americans were very involved with the publication of the Racial Equality Bulletin and the membership of the CFRE.

Conclusion

The Racial Equality Bulletin was an important instrument in the Christian Friends for Racial Equality’s struggle for civil rights in the early 1950s. The Bulletin attacked racism by publishing articles on segregation, discrimination in housing and in the workplace, and the racial problems in South Africa and elsewhere around the nation and world. It promoted community uplift by publishing articles on the importance of ethnic cultural preservation and on the achievements of the civil rights movement in various communities of color. The Bulletin also helped promote the CFRE’s vision of Christian brotherhood across ethnic and racial groups by publicizing interracial social events and educational programs sponsored by the CFRE. The paper and the CFRE were representative of their era – a time when civil rights unrest and non-violent, Christian-based social justice movements were starting to emerge on a national scale. To end, a quote from the Reverend Wm. McDowell:

“Am I my brother’s keeper? (Gen. 4:9)

All men ARE brothers. That truth is written in the fact of life and in the faith of all benign religions. There is only one race upon earth – the human race.”

- Racial Equality Bulletin, October 1951

Copyright © Brooklynn Gregorich 2006

HSTAA 353 Spring 2006

1 Johanna Phillips, “Christian Friends for Racial Equality 1942-1970,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project; David Wilma,Christian Friends for Racial Equality, HistoryLink.org

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.