Injection Safety Overview

Following safe injection practices is key to preventing the spread of infection during health care delivery. Unsafe injection practices include: unnecessary injections, reusing needles and syringes, using a single dose medication vial for multiple patients, giving an injection in an environment that is not clean and hygienic, and risking injury due to incorrect sharps disposal. In this module, you will learn about the causes of unsafe injection practices, how to safely give injections, and how to safely dispose of needles and other sharps.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify common factors that contribute to unsafe injection practices in health care.

- Explain the risks associated with unsafe injection practices and infections caused by them.

- Apply injection safety best practices in health care.

- Describe the 7 steps of a safe injection.

- Demonstrate safe handling and disposal of needles and other sharps.

- Explain the mechanism of safety-engineered syringes.

Learning Activities

-

What Do You Know About Injection Safety? (5 min)

Answer the following true or false questions to gauge your current knowledge about injection safety. Note the questions you answered incorrectly. The information presented in the following learning activities will help you to better understand safe and unsafe injection practices.

How did you do? Misunderstandings about injection safety can lead to injury and infection among patients and health care workers (HCWs). Your responsibility as an IPC focal person is to make sure staff understand and adhere to safe injection practices.

-

Get the Point? (5 min)

The following video summarizes the risks involved with unsafe injection practices, and includes a call to action for professionals and communities to make injections safe.

-

Unsafe Injection Practices (10 min)

WHO estimated that 16 billion health care injections are administered globally each year.1, 2 Often used in patient care, injections can be harmful if they are not performed safely. Unsafe injection practices—including incorrect handling of sharps, reusing syringes and needles, inappropriate administration of single or multidose vials, using non-sterile equipment from unsealed or damaged packaging, and not properly disinfecting the skin or the intra-venous line hubs—put patients and HCWs at increased risk of acquiring bloodborne pathogens and other infections. Many studies have shown that bloodborne pathogens – including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV), and other life-threatening bacterial infections – have spread due to unsafe injection practices. 3, 4

Equipment

The most common reason for an unsafe injection is the re-use of injection equipment. A 2010 study estimated that around 5.5% of injections worldwide were given with re-used injection equipment.5 Re-use can mean:

- The same syringe and/or needle are used for more than one patient.

- The same syringe and/or needle are used to withdraw medication multiple times from a medication container (e.g., vial, IV bags, pen injector cartridges).

- The same syringe is used with a new needle.

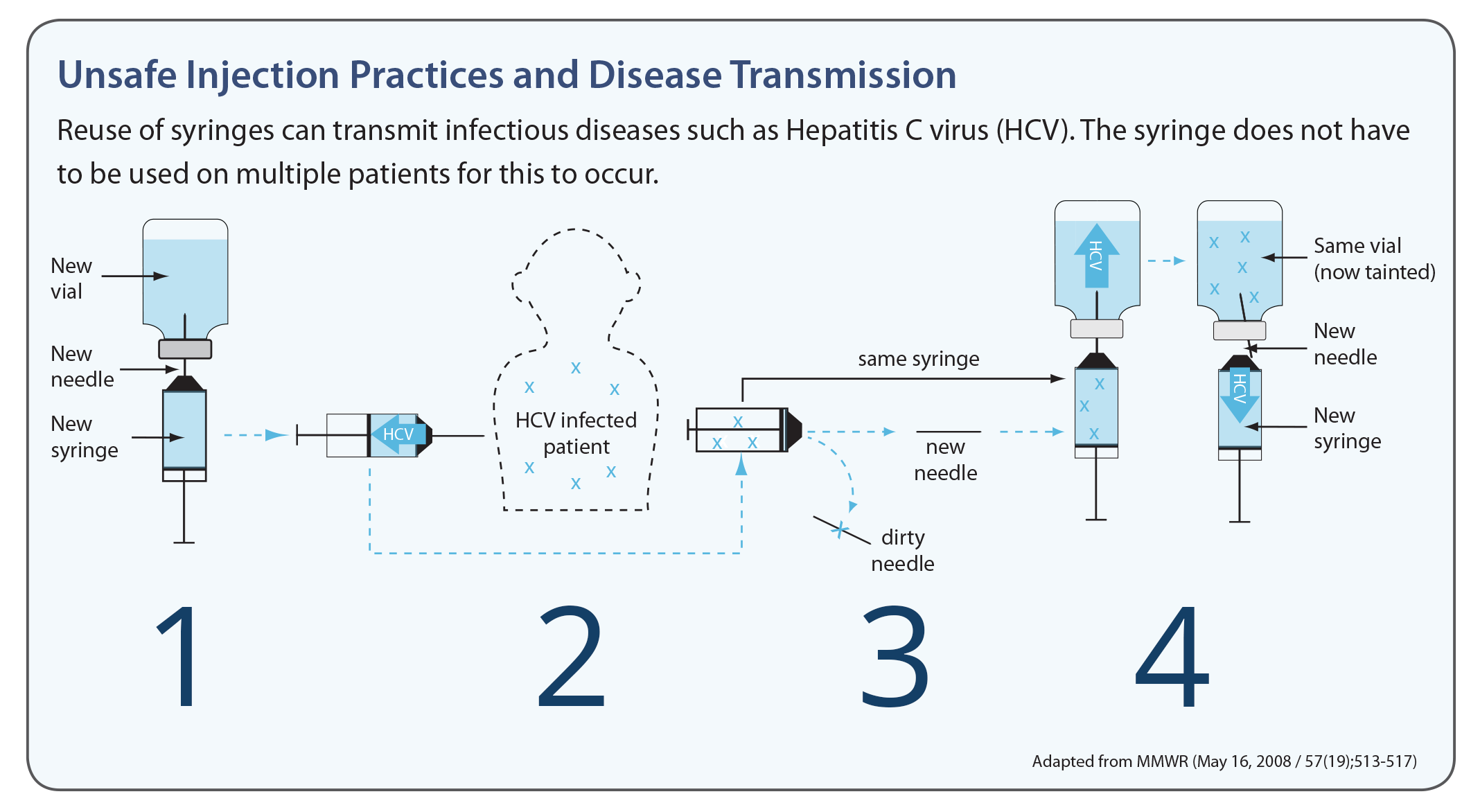

Re-use may directly (via contaminated injection equipment) or indirectly (via contaminated medication vials) expose patients to infections. To better understand the pathways for disease transmission due to unsafe injection practices, click or tap the numbers on the image below to read about how a new needle can become contaminated.

A new needle and syringe are used to draw medication.

When the needle is used on an HCV-infected patient, backflow from the injection contaminates the syringe. Changing the needle does not prevent contamination of the syringe.

When re-used to obtain medication, the contaminated syringe can contaminate the medication vial.

If the contaminated vial is used for other patients, they can become infected with HCV. (Although this example uses HCV, these same principles apply to other bloodborne pathogens.)

Preparing and storing medication

Unsafe injection practices can also result from incorrectly administering medications. During medication preparation, there are multiple steps that can be prone to error or cause contamination of the vial or syringe. Such examples include:

- a medication tray or cart/trolley having more than one injection for different patients;

- a health care worker may pick up the wrong syringe or medication vial for a patient if it is mislabelled or not labelled at all;

- if the injections are not prepared with good sterile technique (for example they can become contaminated from a dirty environment, like the medication tray);

- cotton balls used for disinfecting should not be presoaked; nor should presoaked cotton balls or swabs be stored in containers (see image).

Unnecessary Injections

Many HCWs and patients favour injections over other ways to administer or receive medication. Reducing the number of unnecessary injections can reduce the number of unsafe injections. In addition, unnecessary antibiotic injections can increase antimicrobial resistance. It is important to understand the behavioural and cultural reasons behind unnecessary injections if we are to overcome this problem. To find out why, click or tap on each tab.

Health Care Workers

Some health care workers receive financial incentives to administer medications via injection. This is especially true among private practitioners. Health care workers often believe that medications delivered by injection are more efficacious or that patients will better adhere to treatment. Some health care workers receive financial incentives to administer medications via injection. This is especially true among private practitioners.6, 7, 8

Patients

Some patients insist on requesting to be treated with injections instead of oral medications. Some think that injected medications are superior and are therefore more efficient and efficacious. They believe injections work faster because they are delivered more quickly and directly to the bloodstream.9, 10, 11

Health care workers should avoid giving injections for conditions that can be effectively treated with oral medicines. Injections should be administered only when medically necessary, and after careful review. To reduce infections associated with unsafe injections, infection prevention and control (IPC) programmes should place high priority on elimination of unnecessary injections.

You can apply the IPC multimodal strategy (see the Core Components and Multimodal Strategy module) to injection safety in your health facility.

Examples of using the multimodal strategy to make safe injection practices better include:

- Procuring safety-engineered injection devices in your health facility (“Build it”).

- Educating HCWs on safe injection practices as part of a broader IPC programme, appropriate sharps disposal, and waste management (“Teach it”).

- Monitoring staff adherence with best injection safety practices and availability of equipment (safety-engineered injection devices and safety boxes) at the point of care and providing feedback (“Check it”).

- Using reminders and other communication supports to help inform and reinforce proper injection safety practices (“Sell it”).

- Having those in charge of district health management and health centres ensure that budgets are dedicated for adequate injection equipment (“Live it”).

-

Risk of Harm (5 min)

Unsafe injection practices (including reusing injection equipment) increase the risk of transmission of infectious diseases, such as haemorrhagic fevers, malaria, hepatitis (B and C), and HIV, as well as skin abscesses, nerve damage, and paralysis of the area around the injection site. Some viruses can survive outside the human body (in a syringe, for example) for an extended time. Likewise, there have been many outbreaks of bacterial infections associated with injection delivery. It is important to remember that the risk of transmission increases when the administration route is an IV or when contaminated medicines are re-used.12, 13, 14

Disease Length of time a virus can survive outside the body Risk of transmission from re-used syringe Hepatitis B 1 week 31.0% Hepatitis C 3 weeks (on environmental surface at room temperature) 3.0% HIV 3 days (in dried blood at room temperature) 0.3% These estimated risks in the table above may seem low, but they should be taken seriously. For instance, hepatitis B has the greatest risk of transmission (31%) and can pose a significant risk to HCWs.

-

Review (5 min)

-

Safe Injection Practices: Equipment (5 min)

The rest of this module will cover safe injection best practices. Let us start by looking at the proper equipment needed to perform a safe injection. Within a multimodal strategy this refers to system change (build it).

Part of your responsibility as an IPC focal person is to advise and assist in procuring safe injection equipment for use in your health facility or organization. Therefore, when it comes to injection safety, it is necessary for you to be familiar with appropriate injection equipment and their uses. Let us first learn about syringes. Watch this video on safety-engineered syringes.

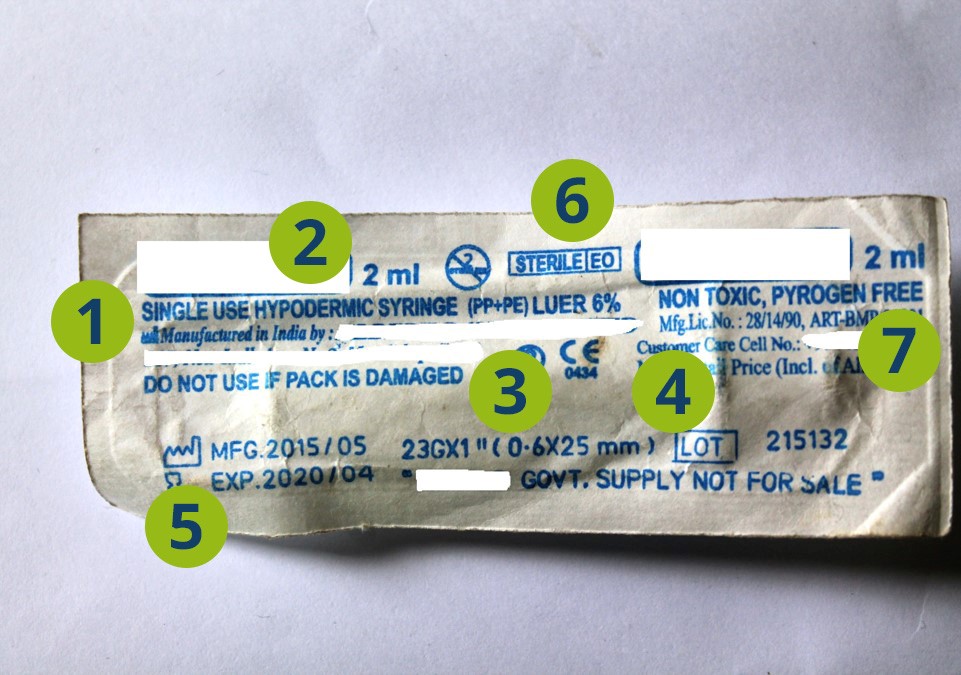

Before using the equipment, always inspect the packaging. Discard it if you find that the packaging has been compromised in any way. Check for punctures, tears, or moisture, and be sure to check the expiration date as well.

Safety-engineered injection device Uses and features Traditional single-use syringe Widely available sterile hypodermic syringe for single-use injection when used properly. Disadvantages include chances of repeated re-use and risk of needle-stick injuries. Auto-disable (AD) syringe for immunization Immunization syringe widely used for fixed-dose immunization with a re-use prevention feature. Re-use prevention (RUP) syringe for therapeutic injections Widely available with full range of sizes, including special sizes. Helps in preventing re-use when the re-use prevention mechanism is activated upon completion of dose. Sharp injury protection (SIP) RUP syringes can also prevent needle-stick injuries among HCWs, waste handlers, and the community. Features include: - a plastic needle shield added to protect the needle;

- the needle is manually retracted inside the barrel after completion of the injection by pulling the barrel backwards; and

- the needle is automatically retracted inside the barrel after pushing a button on the plunger.

-

Vials & IV Bags (5 min)

Many kinds of medication vials are widely available. Click or tap the tabs below to learn more about the different types of vials and ampoules that are most commonly used.s

Single-Dose Vials

Single-dose vials are meant to be used for a single procedure or injection for one patient and one patient only. When using single-dose vials, carefully read the medication label to ensure that the correct dose is being given to the right patient. Unlike multidose vials, single-dose vials do not contain antimicrobial preservatives. Re-use of single-dose vials puts subsequent patients at risk of infections. Infection can occur even when accessing the vial each time with a new needle and syringe, because the open vial can become contaminated by bacteria or viruses in the environment. Many outbreaks have been associated with this unsafe practice.

Intravenous (IV) Bags

Unsafe use of IV bags can lead to bloodborne pathogen transmission — for example, when a common bag of saline or any other IV fluid is used for more than one patient or the same bag is accessed with a syringe that was used earlier to flush another patient’s IV line or catheter. A survey of 5,446 HCWs in 2010 revealed that 9% (490) reported sometimes or always using a common bottle of IV solution as a source of flush for multiple patients.6

Multidose Vials

While multidose vials are common in most countries, WHO does not recommend them for routine use.7The preservatives used in multidose vials do not eliminate microbial contamination, so the use of multidose vials has been associated with many outbreaks. As a review of 60 reports in 2011 noted, “there is good evidence that contamination of multidose or single-dose vials can contribute to infection.”15

-

Injection Safety Implementation Strategy (10 min)

Injection safety is most effective when practiced consistently within a facility. As an IPC focal person, you have the opportunity to change and improve the safety of your facility and prevent the spread of infection. Beyond your facility and community, you may be able to influence safe injection practices in your country as well.

Click or tap the tabs below to read about how a multimodal strategy at the facility or national levels can promote injection safety best practices.

Facility

Promoting injection safety at a facility level will also impact your community. Ensure that all health care workers understand and are sensitive to the risks associated with needle-stick injuries (teach it). As mentioned before, advocacy, education and training will be necessary to achieve this goal. You may also need to distribute and post educational materials for staff and patients in both the inpatient and outpatient areas (sell it). Ask facility-level management to commit to addressing needle-stick injuries by allocating a budget for injection safety (live it), thus enabling the necessary equipment and infrastructure to be put into place and made routinely available (build it).

Remember, data is important. Ongoing evaluation and reporting will help you paint a picture of what needs to be addressed within your facility (check it). Injection safety is a complex problem that requires strategy and collective effort (live it). A comprehensive multimodal strategy is important to address this issue. For more information about the multimodal strategy, refer to the Core Components and Multimodal Strategy module.

National

On a national scale, the key features of a multimodal strategy, which will include a communications campaign, will be different. While you may not participate in these campaigns directly, it is important to be informed about how your country approaches injection safety and advocates for best practice. Find out what your country’s injection safety campaign is by asking the following:

- Has the Ministry of Health and other key stakeholders made a commitment to injection safety ("Live it")?

- Is there a communication strategy for advocacy and awareness, and has it been disseminated ("Sell it")?

- Is there a budget for injection safety at the national level? Are donors helping to finance this effort ("Live it")?

- Are there national education resources for health care workers ("Teach it")?

- Have evaluations and reports been conducted regarding needle-stick injury in my country ("Check it")?

For example, in 2016 the WHO began an injection safety campaign in India. A pilot intervention being conducted in the State of Punjab included a baseline assessment of current practices ("Check it") and the introduction of safety-engineered syringes in the health system ("Build it"). In addition, 40 model injection safety centres are being established at district level ("Live it"), with teaching and nursing institutes serving as training sites ("Teach it"). A communications campaign targeting patients and communities will also be rolled out ("Sell it").

-

Safe Injection Practices: Procedure (10 min)

In addition to using safe equipment, using the proper injection procedures will reduce the risk of injury and potential spread of infection. Watch this video from WHO on the seven steps for giving a safe injection. Teaching staff the correct procedure is one part of your multimodal strategy (training and education, or “Teach it!”).

-

7 Steps to Safe Injections (15 min)

Click or tap each tab to learn more about each safe injection step.

Step 1: A clean workspace

To ensure that injection equipment is not contaminated, it is important to keep the medication preparation area clean. This means removing clutter from all surfaces so that they may be adequately disinfected prior to gathering the necessary injection equipment. This image is an example of a clean workspace. Always:

- Check the patient’s file or prescription to confirm the identity of the patient and the correct dose to be injected.

- Prepare each injection in a clean, hygienic area where there is low risk of blood and body fluid contamination, or of any splashing.

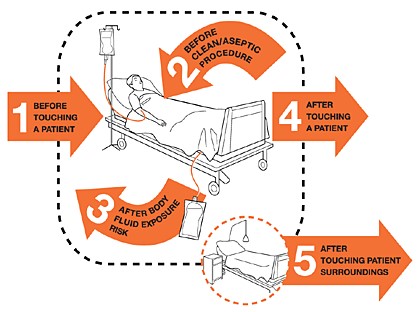

- Clean your hands with an alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water before preparing medication and touching the patient. Follow WHO’s “5 Moments for Hand Hygiene”.

- Disinfect the patient’s skin before injection, using a 60-70% alcohol-soaked swab.

- Collect the used syringe and needle immediately after the injection, and dispose of them without any additional manipulation into the sharps container.

- Manage health care and sharps waste appropriately and safely.

Step 2: Hand hygiene

Be sure to practice proper hand hygiene before preparing and giving an injection (moment 2), and after the injection has been administered (moment 3). When hand hygiene is performed at the right moment, it keeps the patient, other HCWs, and yourself safe.

Gloves and Injections

For routine intradermal, subcutaneous or intramuscular injections, gloves are not required if both your skin and the patient’s are intact. Examples of skin that is not intact are eczema, burns, cuts, scabs, and skin infections. Always wear gloves during vascular access injections; the possibility of blood exposure at the puncture site is high.

Do not use or wash the same pair of gloves for multiple patients. If gloves are used for an injection, hand hygiene is performed before and after glove use. Glove use is not a substitute for hand hygiene. For more information on when to wear gloves, refer to the Personal Protection Equipment module.

Step 3: Sterile, safety-engineered syringe

To reduce and avoid the risk of disease transmission, always use sterile injection equipment. For all injections, WHO recommends safety-engineered injection devices, often called RUP. RUP syringes with a sharps injury-protection feature are highly recommended, and preferable wherever possible.

Be sure that the syringe package is intact, and check that there is no moisture inside. Only syringes and needles from new packets should be used. If you do see that the package has been ripped, torn, or otherwise compromised, safely discard it and use a new one. This image is an example of compromised packaging.

Click or tap this graphic to learn about what information may be on a syringe and needle package.

Type of syringe

In this example, the type of syringe is a single-use hypodermic syringe.

Volume

The volume of this syringe is 2 mL.

Needle Size

The needle size is 0.6x25 mm.

Lot Number

The lot number is 215132.

Expiry Date

The expiry date is 2020/04.

Method of sterilization

The method of sterilization is ethylene oxide. Ethylene oxide is a gas that is used for sterilization of medical equipment that are heat and moisture sensitive. Sterilization with ethylene oxide gas is one of the most common methods for sterilizing syringes.

Type of packaging

The packaging is nontoxic and pyrogen (an agent that causes fever) free.

Some packaging may not include every piece of information listed here.

Step 4: Sterile medication vial and diluent

After checking that your injection equipment is sterile, it is important to know how to handle vials and ampoules without causing contamination. To prevent contamination and spread of infections, use each vial one time for one patient. The preservatives used in multidose vials do not eliminate microbial contamination, so the use of multidose vials has been associated with many outbreaks. As a review of 60 reports in 2011 noted, “there is good evidence that contamination of multidose or single-dose vials can contribute to infection.”15

When preparing a medication vial, wipe the rubber septum (or stopper) with a cotton swab or ball soaked with 60-70% alcohol. Do not touch, fan, or wipe off the disinfectant; allow the septum to air dry. Pierce the septum of the vial with a new and sterile syringe and needle. Insert air into the vial before drawing up the medication. As mentioned earlier, do not leave a needle in the septum of a vial as this can lead to contamination.

Medication in the form of powder must be reconstituted. Reconstitution is the process of adding a liquid to a dry ingredient before administering it. The following aseptic technique must be followed when reconstituting medication.

- Always use a sterile syringe and needle to withdraw the reconstitution solution (liquid) from an ampoule or vial.

- Once the solution is withdrawn, inject the necessary amount of fluid into the single or multidose vial by inserting the needle into the rubber septum.

- Mix the contents of the vial thoroughly until all visible particles have dissolved.

The use of multidose vials should be avoided; if they are used, they should never be used for multiple patients, but only for the same patient. Following the injection, it is important to properly label and safely store the medication. For reconstituted medication in a multidose vial, use the following label details:

- Date and time of preparation

- Expiry date and time

- Type and volume of reconstitution liquid (if applicable)

- Name and signature of the person reconstituting the medication

Step 5: Disinfecting skin

Prior to giving an injection, it is necessary to properly prepare the patient’s skin. Different types of injections require different methods of skin preparation. If the patient’s skin integrity is compromised due to infection or any other skin condition, avoid giving the injection.

The skin should be prepared in different ways depending on the type of injection. For routine intradermal, subcutaneous or intramuscular injections, disinfection with alcohol or another disinfectant is not required.

Injection Type Method Intradermal and sub-cutaneous injections Soap and water Intramuscular injections (therapeutic) Soap and water, (or 60—70% alcohol*) Intramuscular injections (immunization) Soap and water Venous access 60-70% alcohol *Unresolved issue; there is lack of evidence on the need to disinfect the skin before intramuscular injections.

To disinfect with alcohol-based solution:

- Wipe the area with a cotton ball or swab soaked with 60—70% alcohol-based solution. Work from the centre of the area outwards. Avoid wiping the same area with the same swab.

- Wait 30 seconds for the area to air dry.

Presoaked cotton balls that have been stored in containers should not be used for disinfection. This could cause contamination.

Methanol (or methyl alcohol) is not suitable for use on humans and should not be used as a skin disinfectant.

Step 6: Appropriate sharps disposal

After an injection has been given, it is time to safely and correctly dispose of the needle and syringe. Appropriate sharps disposal prevents needle-stick injuries and the spread of infections. To ensure proper disposal after every injection:

- Immediately place syringes and un-capped needles into a sharps container.

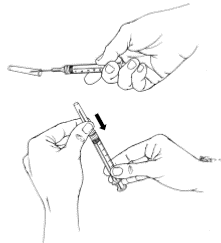

- Never recap a needle.

- Do not bend, break, manipulate, or manually remove the needle or syringe.

- A sharps container must be within arm’s reach of where sharps are used (at the point of care).

Follow these steps if for any reason the medicine has been drawn into the syringe, but the injection must be delayed:

- Re-cap the needle using the one-handed ‘scoop’ technique. Do not use your other hand to re-cap the needle; it is safer to place the needle cap on a flat surface and scoop the needle inside the needle cap. This protects your other hand from an accidental needle-stick injury. Once the needle is inside, you may use your other hand to secure the cap in place. This image depicts this technique.

- Label and store the syringe according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

- If the needle comes into contact with a non-sterile surface, immediately discard the syringe.

Step 7: Appropriate waste management

Managing sharps waste is important not only for the safety of your facility and patients, but also for the community. Exposure to needles that have not been safely disposed of can lead to risk of injury and potential spread of disease. For example, contaminated needles are sometimes dumped in public waste sites; children can find these sharps in the open and play with them as toys.

Sharps containers are puncture-resistant containers that safely store used sharps, as seen in this photograph. When a sharps container is about three quarters filled, it must be sealed and stored in a secure place before final disposal. Opening a sharps container prior to its final disposal can lead to potential needle-stick injury and/or infection. (For more information about appropriate sharps handling and disposal methods, and waste management and disposal, refer to the Waste Management module.)

In cases when proper sharps containers are difficult to procure, you may provide low-cost alternatives. Improvised sharps containers may be made from throw-away items, such as metal containers, plastic bottles, or durable cardboard boxes. Label your improvised sharps container as “sharps waste”. Once it is full, make sure you can completely close and tightly seal this container to prevent it from being opened before final disposal.

-

Unsafe Injections (5 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module we have covered unsafe injection practices, including re-use of syringes and/or needles, contamination of medication vials, and giving unnecessary injections. Safe injection practices can reduce the risk of harming the patient or other health care workers and prevent the spread of bloodborne pathogens like HBV, HCV, HIV, and bacterial pathogens.

By now, you should be familiar with safe injection equipment and be able to inspect packaging for possible contamination. Remember to dispose of any injection equipment that you suspect may have been contaminated.

-

References

- 1Werner BG, Grady GF. Accidental hepatitis-B-surface-antigen-positive inoculations: use of e antigen to estimate infectivity. Ann Intern Med 1982;97:367–9.

- 1Prüss-Ustün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005 Dec;48(6):482-90.

- 2Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Hutin YJ. The global burden of disease attributable to contaminated injections given in health care settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2004 Jan;15(1):7-16.

- 3Patel, DA 2012; Okwen, MP 2014; Jung, SY 2015; Vun MC, 2016.

- 4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks and Patient Notifications in Outpatient Settings, Selected Examples, 2010-2014.

- 5Pépin J, Abou Chakra CN, Pépin E, Nault V. Evolution of the global use of unsafe medical injections, 2000-2010. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 4;8(12):e80948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080948. eCollection 2013.

- 6Reeler AV. Anthropological perspective on injections: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(1):135-43. Luby SP et al. The relationship between therapeutic injections and high prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Hafizabad, Pakistan.

- 7WHO Best Practices for Injections and Related Procedures Toolkit Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 Mar.

- 8Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011 Oct-Dec;26(4):449-70. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1112.

- 9Reeler AV. Anthropological perspective on injections: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(1):135-43.

- 10Dentinger et al. Injection practices in Romania: progress and challenges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004 Jan;25(1):30-5.

- 11Altaf et al. Determinants of therapeutic injection overuse among communities in Sindh, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2004; 16(3) 25-38.

- 12Fischer GE, Schaefer MK, Labus BJ, Sands L, Rowley P, Azzam IA, Armour P, Khudyakov YE, Lin Y, Xia G, Patel PR, Perz JF, Holmberg SD. Hepatitis C virus infection from unsafe injection practices at an endoscopy clinic in Las Vega, Nevada, 2007-2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Aug 1;51(3):267-73. doi: 10.1086/653937.

- 13Gutelius B, Perz JF, Parker MM, Hallack R, Stricof R, Clement EJ, Lin Y, Xia GL, Punsalang A, Eramo A, Layton M, Balter S. Multiple clusters of hepatitis virus infection associated with anesthesia for outpatient endoscopy procedures. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jul;139(1):163-70. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.053. Epub 2010 Mar 27.

- 14Moore ZS, Schaefer MK, Hoffmann KK, Thompson SC, Xia GL, Lin Y, Khudyakov Y, Maillard JM, Engel JP, Perz JF, Patel PR, Thompson ND. Transmissio of hepatitis C virus during myocardial perfusion imaging in an outpatient clinic. Am J Cardiol. 2011 Jul 1;108(1):126-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.010. Epub 2011 Apr 29.

- 15Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, Benyamin RM, Caraway DL, Helm Ii S, Wargo BW, Hansen H, Parr AT, Singh V, Hirsch JA. Assessment of infection control practices for interventional techniques: a best evidence synthesis of safe injection practices and use of single dose medical vials. Pain Physician. 2012 Sep-Oct;15(5):E573-614.