Module 4: Acute Interventions to Care for GBV Survivors

In this module, you will learn about health and safety interventions for survivors of recent gender-based violence.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Name the three key areas of intervention for GBV survivors.

- Identify situations that require immediate referral.

- Describe the minimum medical interventions that must be offered to a GBV survivor.

- Describe the process of physical examination.

- Explain the basic protocols for preventing unwanted pregnancy, HIV PEP, and STI treatment.

- Describe the components of a safety plan.

- List possible responses to address reluctance to seek psychological help.

- Describe the components of a social support plan.

- Distinguish between helpful and unhelpful coping strategies.

Learning Activities

-

Case Study: Andiswa’s Story (5 min)

Andiswa, the 26-year-old woman you treated for a broken wrist in Module 3, has returned to your clinic. At that last visit, she disclosed to you that her partner is abusive; today, she’s here because he beat and raped her last night. At her previous visit, Andiswa grew to trust you.

Take a moment to reflect: What should you do first to help Andiswa with her physical condition? What should you do first to help her with her emotional condition? What should you do to help Andiswa before she leaves the clinic today?

In this module, you will learn about what steps to take to care for a survivor of violence after establishing a safe environment and taking her initial history (debriefing her). You will learn about three areas of intervention: safety, medical needs, and mental needs.

-

Reading: Overview (5 min)

Most professionals have just a short time (10 minutes or so) with a patient. What can you do in such a brief time to help GBV survivors like Andiswa?

What you cover in that short period might differ based on how chronic or immediate the trauma is. Some patients will have just experienced GBV, others may have experienced an incident two years ago, while others may be experiencing long-term abuse and violence. Much of safety assessment and planning and psychosocial support are important regardless of whether the event just happened within the past few days or weeks or whether it happened years ago. Some information, such as how to deal with a pregnancy that was the result of rape, can be shared months after an assault. Other medical interventions, such as STI prophylaxis, must be done immediately following an instance of GBV.

When seeing a GBV survivor, first, make sure there are no critical injuries that need to be attended to. These include life-threatening injuries or otherwise urgent care needs that must be treated. Either treat the patient or refer the patient to a provider or facility where they can get the urgent care they need. Should the survivor require referral, make sure to state in your referral letter that the patient has been sexually assaulted.

Click or tap on the timeline to about what you should do for survivors in the short-term aftermath of an experience of GBV at each phase of the visit.

Establishing care

- Create a safe environment for the survivor to have her exam and share her story (covered in Module 3)

- Take patient history

- Establish a rapport through active listening and good communication (covered in Module 2)

Scenario: Andiswa arrives at the clinic

The nurse seats her and her friend in a quieter corner of the waiting area and moves her to a private exam room as soon as she can. The nurse then checks to make sure that the person or people who assaulted Andiswa are not present. She asks questions about what happened, explains the protocols and procedures that they will follow throughout the visit, and begins to ask questions. The nurse communicates this information kindly, professionally, and supportively to establish a good relationship with Andiswa.

Addressing immediate needs

- Assess suicide risk

- Conduct physical exam and care for injuries

- Provide a supportive presence during the examination and treatment for injuries

Scenario: Andiswa has the physical examination

The nurse asks some questions to assess Andiswa’s risk of suicide. She then begins the physical exam, explaining each step as she goes. A patient advocate and Andiswa’s friend are present to comfort and reassure her during the physical exam.

Next part of visit: Attending to social, medical and mental needs

- Assess eligibility for and offer emergency contraception, STI prophylactics, an HIV test, and PEP for HIV, hepatitis B, and tetanus

- Develop a safety plan

- Identify social support, encourage coping skills, and provide referral for ongoing psychosocial care

Scenario: Andiswa has additional counselling and care

The nurse discusses the risk of pregnancy and HIV and sexually transmitted infections and provides prophylaxis, treatment, and referral. Next, she talks with Andiswa to determine whether she has a safe place to go and helps her plan her next steps. The nurse explains what resources are available for social and psychological support and counselling. Then the nurse teaches Andiswa a method to help her calm herself when she begins to feel stressed.

Andiswa leaves the clinic with a follow-up appointment scheduled and referrals to the social worker, a sexual assault survivors’ group, and the number of the local police in case she should wish to file a report.

Note: National directives state that health services must be provided to survivors regardless of whether they have opened criminal cases. LGBTQ, older persons, MSM, survivors with disabilities, survivors with mental health problems, refugees and migrants, sex workers, and others may need additional, specialized care and interventions. Module 5, which covers referrals, will discuss how to map resources for members of these groups.

-

Reading: Assess Suicide Risk (10 min)

Nurse: Do thoughts of causing harm to yourself come up for you since this has been happening, Andiswa?

Andiswa: I have been having them. I think that it would be better to be dead. I am tired of feeling sad and angry. I don’t want to feel anything. It’s not worth living anymore.

Nurse: How strongly do you feel the urge to take your life?

Andiswa: It’s strong! Sometimes I think, I can just end it now. All it would take is some rat poison and I could be rid of this life.

Nurse: Have you ever tried to harm yourself?

Andiswa: Once, after my husband beat me very badly—we were newly married—I did take some Panadol, hoping it would kill me, but I just slept. When I woke, I decided that I must try to make my marriage work. I have endured so much now, I think I would have been better off if I had died back then.

Nurse: You have endured a great deal and yet you have strength to come here today for help. Do you ever hear voices telling you to harm yourself?

Andiswa: No. I sometimes dream about it, though.

Nurse: Do you have a plan for this now?

Andiswa: What do you mean, a plan? Sometimes I think I could take some poison or turn on the gas. I don’t know. There are many ways to end a life. I don’t know what to do. I love my family and I have always wanted to be a mother. But I can’t go on living like this.

Assess Suicide Risk

After dealing with the physical injuries, assess suicide risk. Suicidal ideation means a person is having thoughts of suicide.

First ask the patient, “How often do thoughts of suicide come up for you?”

If the patient says they have been having suicidal thoughts, ask these follow-up questions.

- “How strongly do you feel the urge to take your life?”

- “Have you ever attempted to kill or harm yourself?”

- “What is your plan for how you would harm yourself?”

- “What access do you have to the materials you would need to carry out that plan?”

- “Do you ever hear voices or receive messages telling you to hurt yourself?”

The patient’s answers to the questions listed above will help you determine the level of suicide risk. Click or tap on each level of risk to read about responses to look out for.

High risk

- Having a detailed plan

- Having knowledge about where to obtain the means of suicide (gun, drugs, rope, etc.)

- Having underlying mental health conditions such as hearing

Moderate risk

- Attempting suicide in the past

Low risk

- Having no plan—just general thoughts of suicide, harm, or dying. However, it should be kept in mind that survivors of assault are at higher risk of suicide than the general population.

Based on the survivor’s responses to the follow-up questions, use your clinical procedures regarding risk management and refer to emergency care. This could include identifying a “safety person” to watch over the survivor while at the clinic. For those at low to moderate risk, see the section later in this module on psychosocial support. Refer to trained social workers and schedule follow-up sessions, if possible.

-

Reading: Physical Exam & Treatment of Injuries (10 min)

As stated before, any serious or life-threatening emergent injuries should be treated immediately. After addressing emergent injuries, getting an initial history, and assessing suicide risk, address a survivor’s physical needs.

If you are qualified to collect forensic evidence, this will be part of the physical examination. If there is not someone present to collect forensic evidence, the survivor should be referred for physical examination. Findings should be recorded completely and legibly and signed by the person who performed the exam. A provider can use the J88 form or another document. See Resources for the J88 form and a sample form.

Click or tap on each aspect to read more about it.

Physical Examination

When conducting the physical exam, be sure to do the following:

- Explain the medical examination, what it includes, why and how it is done to avoid the exam itself becoming another traumatic experience. Also, give the patient a chance to ask questions.

- Ask the patient if she wishes to have a female doctor (especially in cases of sexual violence). Do not leave the patient alone (e.g., when she is waiting for the examination).

- Ask her to disrobe completely and to put on a hospital gown, so that hidden injuries can be seen. Examine areas covered by clothes and hair.

- If she has experienced sexual violence, examine her whole body—not just the genitals or the abdominal area.

- Do not expose the survivor’s body completely during the examination. Expose only the area you are examining and cover the rest.

- Examine serious and minor injuries. Examine all injuries, including the size and depth and possible mechanism of injury.

- Note emotional and psychological symptoms as well.

- Throughout the physical examination, inform the patient what you plan do next and ask permission. Always let her know when and where touching will occur. Show and explain instruments and collection materials.

- Patients may refuse all or part of the physical examination. Allowing her a degree of control over the examination is important to her recovery.

- Both medical and forensic (legal) specimens should be collected during the examination. However, this should only be done by a care provider who has been specially trained to conduct the forensic examination and collect forensic specimens. If there is no one at your facility trained to provide this service, then you must immediately refer the survivor to a facility that can and arrange for her transportation there.

- Document the findings on the appropriate forms. The physical exam can be done using the J88 form or using another form. If using another document and transferring to the J88, note that the person who signs the J88 must be the person who conducted the exam.

Treatment of Injuries

Refer patients with severe, life-threatening conditions for emergency treatment right away. Treat patients with less severe injuries (superficial wounds, etc.). The patient may need:

- Antibiotics to prevent wounds from becoming infected

- A tetanus booster or immunisation (according to local protocols)

- Medications for the relief of pain, anxiety, or insomnia

-

Reading: Prevention of Unwanted Pregnancy (5 min)

Emergency contraception

Health care professionals should discuss the potential risk of pregnancy for girls and women of reproductive age. Offer a pregnancy test to any survivor who presents within five days of a sexual assault and is at risk of pregnancy. If the test is negative, the provider should offer emergency contraception as soon as possible.

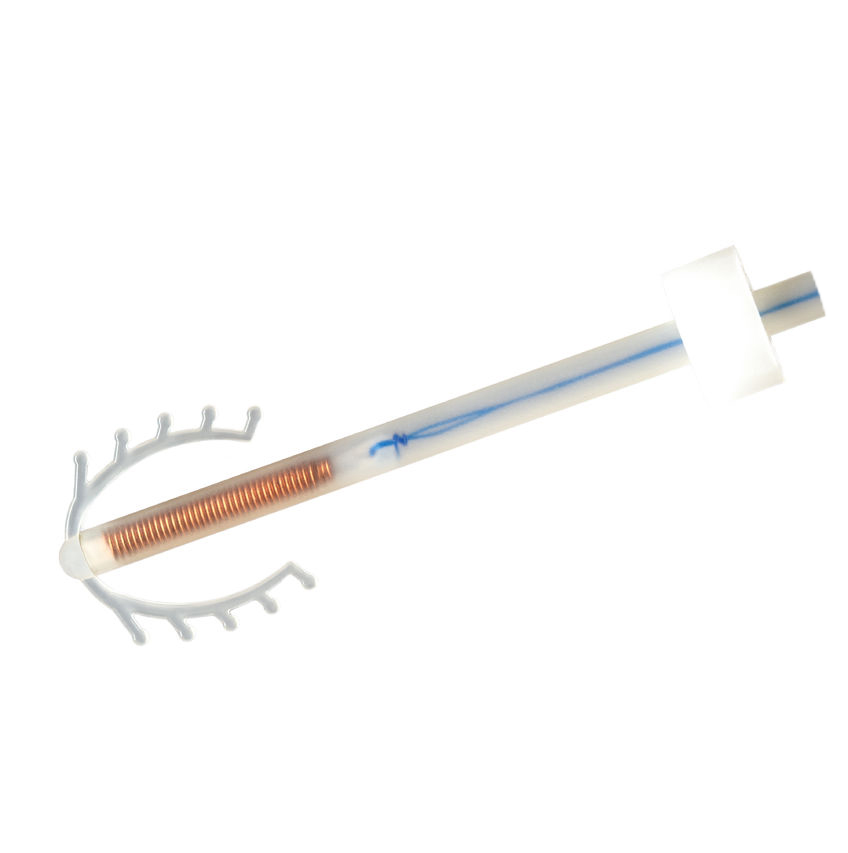

Two kinds of emergency contraception are available in South Africa: the emergency contraceptive pill and the copper-bearing intrauterine device. Click or tap on each tab to read more about emergency contraception.

Emergency contraceptive pill (ECP)

The emergency contraceptive pill is most effective if given within 72 hours (3 days) of the assault, but can be given up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected sexual intercourse. ECP can be progestogen-only or combined oestrogen-progestogen. Progestogen-only is more effective and has fewer side effects. However, if progestogen-only options are not available, the survivor can be offered the oestrogen-progestogen ECPs, along with anti-emetics (if available) to prevent nausea.1

South Africa National Contraception Clinical Guidelines, 2012ECP will not stop a pregnancy that is already established, nor will it harm the foetus.

Copper-bearing intrauterine device

The most effective form of emergency contraception is the Cu IUD. The Cu IUD is equally effective throughout the 120-hour window. It is also a good choice if the survivor is interested in ongoing pregnancy prevention. If the survivor is not interested in ongoing contraception, the Cu IUD can be placed for emergency purposes and later removed during the first menstrual period. Cu IUD should only be placed by a healthcare provider who is qualified to insert Cu IUD. The survivor must meet medical eligibility criteria; consult the standard protocol for Cu IUD placement. Since there is a high risk of infection (STIs) in cases of rape, Cu IUD should be placed under antibiotic cover.2

CTOP

Information about choice on termination of pregnancy (CTOP) should be offered when:

- A woman presents after the time required for emergency contraception (5 days)

- The emergency contraception fails

- The woman is pregnant as a result of rape

In South Africa , women can choose termination of pregnancy for any reason up to 13 weeks of pregnancy, and in cases of rape, with a documented case number until 20 weeks of pregnancy.

-

Reading: Prevention of HIV & Sexually Transmitted Infections (5 min)

HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Antiretroviral medication for post-exposure prophylaxis is highly effective in preventing HIV infection when taken soon after exposure to HIV. Offer HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (HIV PEP) to eligible survivors presenting within 72 hours of a sexual assault. The healthcare provider and the survivor should determine whether HIV PEP is appropriate. When discussing the HIV risk, the following factors should be taken into account:

- HIV status of the survivor, if known

- HIV status of the perpetrator, if known

- Assault characteristics, including the number of perpetrators

- What kind of exposure to HIV occurred and the likelihood of HIV transmission

- The limitations of PEP. PEP must be taken correctly and consistently for the full 28 days to be effective. Although PEP is highly when taken within 72 hours of exposure, it is not 100% effective and is not effective if the person is already infected with HIV (such as when they are in the window period).

- Side-effects of the antiretroviral drugs used in the PEP regimen

Follow the facility’s standard PEP protocol. At the initial consultation, provide counselling and obtain consent for HIV testing if the survivor’s own HIV status is negative or unknown. If the survivor is not able to be counselled due to injuries or emotional state, arrange for follow-up counselling within 72 hours.

Persons at risk for HIV infection should be counselled to use condoms if they engage in sexual intercourse.

TestingIt is recommended that survivors of sexual violence undergo HIV testing prior to giving PEP; however, if they refuse testing, they should still be offered PEP starter pack. Patients who refuse testing should be provided with only three days of PEP with the intention that they will come back within three days for the test. Patients must be informed that PEP for three days will not protect them from contracting HIV, according to the national protocol.

PEP for Infants and ChildrenInfants and children can be eligible for PEP. Follow the facility protocol for providing PEP to infants and children. Children over age 12 can give their own consent to be tested for HIV. Where there is a challenge in obtaining consent for HIV test for children under age 12, especially when the child’s caregiver is suspected of abusing the child, consult with the facility manager to determine next steps in involving a designated child protection organisation or the Children’s Court to obtain consent. See Resources for definition of a caregiver.

National HIV Counselling and Testing Policy advises that healthcare providers can initiate HIV testing in cases of suspected sexual assault against a child. The Children’s Act also permits HIV testing in cases where it is in the best interest of the child.Patients with HIVPatients with HIV infection should not use PEP; rather, they should receive care and antiretroviral therapy. Screen for adherence and refer them for adherence support, as the current trauma may affect their ability to adhere to HIV treatment.

Administering PEPIf HIV PEP is used, start the regimen as soon as possible and before 72 hours have gone by since the assault. It is important to provide adherence counselling because many survivors of sexual violence do not successfully complete the 28-day regimen. Reasons for lack of adherence may include:

- Side effects (nausea and vomiting)

- Painful memories of the rape/ flashbacks

- Reluctant to be reminded of the trauma

- Too overwhelmed or depressed to adhere to treatment

- Experiencing psychiatric symptoms that keep them from daily functioning, such as problems with memory, concentration, etc.

Because an HIV-test is required before starting the 28-day PEP regimen, it is possible that a survivor will learn they are HIV-positive during this clinic visit. This can cause additional trauma to what she has already experienced (i.e., the sexual assault). It is important to provide non-judgmental care and support and link her as soon as possible to HIV care and treatment services.

STI post-exposure prophylaxis

- Chlamydia

- Gonorrhoea

- Trichomoniasis

- Hepatitis B

- Take blood to test for hepatitis B Ab and Ag

- Administer hepatitis B vaccine for patients over 14 years, born in South Africa, and reporting within three weeks

- If a child less 14 years old was not immunised, collect blood for hepatitis B testing and make a follow-up appointment within seven days. If indicated by test results, give the hepatitis B vaccine.

- Syphilis3

- Presumptive treatment for anyone over age 14

- For children less than 14 years of age:

- Perform an RPR test

- If RPR is negative, schedule a follow-up RPR in the months. Counsel the survivor on the importance of the follow-up test and, if possible, link to support for keeping the appointment.

- If RPR is positive, follow the national STI management guidelines protocol for syphilis treatment.

Infants and children can receive STI prophylaxis. Follow the facility protocol for STI prophylaxis for infants and children.

The resources section has PEP treatment guidelines from South Africa Adult Primary Care Manual 2016-17.

-

Knowledge Check: Physical Needs (10 min)

-

Reading: Safety Assessment & Planning (15 min)

Safety assessment always comes first and should be briefly assessed for everyone. Assessing safety includes determining whether the survivor has thoughts of suicide, is at immediate risk of harm, and has a safe place to go to. Click or tap on each tab to read more.

Immediate Risk

Assess the survivor’s immediate risk of violence from the perpetrator. Some survivors will know they are in immediate danger and may be afraid to go home. A person who is assaulted often knows the person who assaulted her, and it often happens at home. If it was someone she knows, discuss whether it is safe for her to return home. People who have experienced sexual violence often know the perpetrator and may not need help assessing their safety. For other survivors, you may need to help them assess their immediate risk.

Survivors who answer “yes” to at least three of the following questions may be at especially high immediate risk of violence.

- Has the physical violence happened more often or gotten worse over the past 6 months?

- Has he ever used a weapon or threatened you with a weapon?

- Has he ever tried to strangle you?

- Do you believe he could kill you?

- Has he ever beaten you when you were pregnant?

- Is he violently and constantly jealous of you?

If there seems to be immediate high risk, then you can say “I’m concerned about your safety. Let’s discuss what to do so you won’t be harmed.” You can consider options such as contacting the police and arranging for her to stay that night away from home.

Safety Planning

After you assess a survivor’s immediate risk, you should help her create a safety plan. Some women may not think they need a safety plan because they do not expect that the violence will happen again. Explain that partner violence is not likely to stop on its own--it tends to continue and may over time become worse and happen more often.

Even survivors who are not facing immediate serious risk could benefit from having a safety plan. If they have a plan, they will be better able to deal with the situation if violence suddenly occurs.

The resources section has questions to ask a survivor when creating a safety plan.

You can advise a survivor to contact police as they may be able to help in a violent situation.

If you see a patient more than once, assessing and planning for safety is an ongoing process – it is not just a one-time conversation. Her needs and situation, options and resources may change over time. It can be helpful to check in briefly each time you see her.

The following are elements of a safety plan and questions you can ask a survivor to help her make a plan, whether or not they are planning to leave an abusive partner.

Safety planning Safe place to go If you need to leave your home in a hurry, where could you go? Planning for children Would you go alone or take your children with you? Transport How will you get there? Items to take with you Do you need to take any documents, key, money, clothes, or other things with you when you leave? What is essential? Can you put together items in a safe place or leave them with someone, just in case? Financial Do you have access to money if you need to leave? Where is it kept? Can you get it in an emergency? Support of someone close by Is there a neighbour you can tell about the violence who can call the police or come with assistance for you if they hear sounds of violence coming from your home?

Safety When Leaving an Abusive Partner

If it is not safe for the woman to return home, make appropriate referrals for shelter or safe housing, or work with her to identify a safe place she can go to (such as a friend’s home or church). If she has decided that leaving is the best option, advise her to make her plans and leave for a safe place before letting her partner know. Otherwise, she may put herself and her children at more risk of violence.

Where and how: A survivor must identify a safe place to go and determine how she will get there. If she has children, she must decide whether to bring them with her.

Important items: When leaving home, the survivor will need to think of what items to bring with her such as documents like identity papers, birth certificates, Road to Health Booklets for her children, keys, clothing, toilet items, food and diapers, etc. These items can be kept with a trusted friend or in another safe place for when she needs them, if possible. Access to money, especially in an emergency, is very important. Help her determine whether to have cash, access to a bank account, or other financial resources.

Support: When possible, it can be helpful to identify a trusted neighbour who can call for help or bring assistance if they hear sounds of violence coming from the survivor’s home. Alternatively, a signal or password could be used on the phone to let the neighbour know that something is amiss.

Safety While Living With an Abusive Partner

There are some steps a survivor can take to try to stay safe if she decides to stay at home with an abusive partner. Click or tap on each topic to read more about it.

Safe place in house

Ask the patient to identify safe areas of the house where there are no weapons and there are ways to escape. If arguments occur, tell her she should move to those areas. If she cannot avoid discussions that may escalate with her partner, advise her to try to have the discussions in a room or an area that she can leave easily and to avoid rooms with weapons. For example, a partner might become violent after drinking. The patient could try to stay in rooms with exits if she knows he’s been drinking.

Support

If possible, the survivor should always have a phone accessible and know what numbers to call for help. Tell the survivor to let trusted friends and neighbours know of the situation and develop a plan and signal for when she needs help.

Escape

The survivor should practice how to get out of the house or compound safely and she should practice with her children.

Harm prevention

She should make sure that weapons like guns and knives are locked away and as inaccessible as possible.

-

Reading: Address Psychological Issues (5 min)

Mental and emotional health are critical components of overall health. Psychological support in the first period after a trauma—referred to as psychological first aid—can reduce initial stress and distress, improve the survivor’s ability to cope in the short- and medium-term, and orientate survivors to additional resources for care and support. For many survivors, this may be the only time they access mental health care.4

Not all survivors of GBV are affected in the same way. Do not assume that rape or violence will always result in severe mental health issues for survivors. Provide support and care that addresses the needs and concerns of each individual survivor. Any steps or interventions that are not completed during the initial visit can be continued in return visits, if appropriate, or through supported referrals.

Ask the survivor about issues that are most important to her right now: “What would help the most if we could do it right away?” Then help her to identify and consider her options.

You may come across patients who are reluctant to seek support. The table below show possible responses to different concerns.

Concern What You Can Do Feeling embarrassed or weak because of needing help

Feeling guilty about receiving help when others are in greater need

Worrying that they will be a burden or depress others

Provide reassurance that asking for help after GBV is normal and can be very helpful. Fearing that they will get so upset they will lose control Assure the survivor that there is no “right” way to respond to an experience of violence and that support providers are here to help Doubting that support will be available or helpful Reassure her that you can refer her to reliable support services.

Say: “Others have found these services to be helpful. Would you be willing to try?”

Having tried to get help and finding that help wasn’t there (feeling let down or betrayed). Reassure her that while she may have had problems in the past, you can refer her to reliable support services. For each concern, list 1-2 things you can do to help address it. Then tap the compare answer button to read an expert’s answer.

-

Reading: Social Support (10 min)

Fostering connections as soon as possible and assisting survivors in developing and maintaining social connections is critical to recovery. By feeling connected socially, survivors have increased opportunities for knowledge essential to recovery. They will also have more opportunities for a range of social support activities including:

- Practical problem-solving

- Emotional understanding and acceptance

- Sharing of experiences and concerns

- Clarifying reactions

- Information about coping

What Is Social Support?

Click or tap on each box in the graphic to read about social support.

Social connection: feeling like you fit in and have things in common with other people, having people to share activities.

Emotional support: hugs, a listening ear, understanding, love, acceptance.

Advice and information:having people show you how to do something or give you information or good advice, having people help you understand that your way of reacting to what has happened is common, having good examples to learn from about how to cope in positive ways with what is happening.

Physical assistance: having people help you perform tasks, like carrying things, fixing up your house or room, and helping you do paperwork.

Reliable support: having people reassure you that they will be there for you in case you need them, that you have people you can rely on to help you.

Feeling needed: feeling that you are important to others, that you are valued, useful and productive, and that people appreciate you.

Reassurance of self-worth: having people help you have confidence in yourself and your abilities, that you can handle the challenges you face.

Material assistance: having people give you things, like food, clothing, shelter, medicine, building materials, or money.

Good social support is one of the most important protections for any woman suffering as a result of GBV. When women experience abuse or violence, they often feel cut off from normal social circles or are unable to connect with them. This may be because they lack energy or feel ashamed.

One step that a healthcare provider can take with a survivor is to help her identify sources for positive social support. When discussing a survivor’s social support, encourage her to identify people she thinks are most likely to be supportive. Being supportive could mean helping with emotional support (understanding, acceptance) or material support (financial help, child care, help with physical tasks). If she feels disconnected from her social support network, encourage her to think of other people she could reach out to as sources of social support, such as clergy, a teacher, or a neighbour.

Let survivors know that some people choose not to talk about their experiences and that spending time with people one feels close to without talk can be helpful even if she does not tell them about the event(s). She still can connect with family and friends, and spending time with people she enjoys can distract her from her distress.

For GBV survivors who have become withdrawn or socially isolated, ask them:

- When you are not feeling well, who do you like to be with?

- Who do you turn to for advice?

- Who do you feel most comfortable sharing your problems with?

- What do you most need help with?

- Who are people you could approach for that type of support?

- When would be a good time and place to approach the person?

- What would you ask them to do to help you?

Other questions to ask are:

- Is there anyone (family member, friend, trusted person in the community) you can talk to?

- Do you have anyone who could help you with resources you need (money, housing, child care)?

In addition to identifying people to be supportive, you may want to help her to identify past social activities or resources that may provide direct or indirect psychosocial support (for example, family gatherings, visits with neighbours, sports, community and religious activities). Encourage her to participate.

By the end of the discussion, the survivor should have an informal list of people and resources that she can use for social support.

-

Reading: Coping Strategies (5 min)

After GBV events a survivor may find it difficult to return to her normal routine. It’s important to remind the survivor about coping strategies she has used in the past and encourage her to take care of her immediate physical needs. Use the brief time you have with the patient to encourage her to use any coping skills she already has. Discuss and plan together. Let her know that things will likely get better over time.

Talk to her about her life and activities. Build on her strengths and abilities, asking how she has coped with difficult situations in the past. Are these strategies she could use to get through this situation?

Click or tap on each tab to read about coping strategies.

Unhelpful coping strategies

- Isolation from family and friends.

- Staying in bed all day.

- Alcohol or substance use.

- Violent behaviour toward oneself or others.

- Increased sexual activity.

Helpful coping strategies

- Engaging in activities that you find enjoyable or relaxing.

- Keeping a regular sleeping and eating schedule.

- Regularly exercising or doing some physical activity.

- Using relaxation techniques.

Encourage the survivor to:

- Continue normal activities, especially ones that used to be interesting or pleasurable.

- Identify relaxing activities that they can do to reduce anxiety and tension.

- Keep a regular sleep schedule and avoid sleeping too much. Keep regular sleeping and waking times. Avoid napping during the day is also helpful.

- Eat regularly despite possible changes in appetite.

- Participate in community and other social activities, as much as possible.

- Engage in regular physical activity.

- Avoid using self-prescribed medications, alcohol or illegal drugs to try to feel better.

- Recognize thoughts of self-harm or suicide and come back as soon as possible for help if they occur.

If someone is acutely distressed and is having difficulty managing the intensity of their feelings, these strategies may be helpful:

- Tell the survivor when she is distressed to imagine her favorite place. Create a detailed picture of it in her mind.

- Tell her to squeeze something (play dough, clay, silly putty, her fists, a stress ball).

- Tell her to drink a cold glass of water or splash cold water on her face.

-

Activity: Coping Skills: Relaxation Exercises (10 min)

Relaxation exercises are one way to help cope with anxiety, fear and stress. If you do not have enough time during your initial encounter with the survivor to teach these techniques, you could ask if she already knows these techniques, and, if she does, encourage her to use them. You could also share them with her during a follow-up visit or have the social worker share these techniques with her.

You can also use these techniques yourself to cope with stress. Click on the tabs to learn about two kinds of relaxation exercises.

Breathing5

Take in air for a count of four seconds, hold it in for four seconds. Then, breathe out for four seconds, then hold your breath for four seconds. Repeat the cycle. Continue to focus on this breathing pattern until you feel calmer.

Take a few minutes to practice this technique now.

Progressive muscle relaxation

Muscle tension is commonly associated with stress, anxiety, and fear as part of a process that helps our bodies prepare for potentially dangerous situations. You may not notice that you are keeping your muscles tense, but you may feel the ache or stiffness in your shoulders, neck, jaw or other parts of your body. Muscle tension is also associate with backaches and tension headaches.

Progressive muscle relaxation 6is a technique that you can practice regularly to reduce tension, stress, and anxiety. In this exercise, you tense up a particular muscle or group of muscles in your body and then relax them, moving from one part of your body to another.

Preparing to do progressive muscle relaxation

Talk to your doctor before trying this technique if you have any injuries or past physical issues that may cause muscle pain. Do not practice this technique after consuming alcohol or after a heavy meal. You can do this technique sitting or lying down.

- Choose a place to do it that is comfortable and has minimal distractions (for example, turn off the television or radio, turn the lights low, and put your mobile on silence).

- Take off your shoes.

Instructions for progressive muscle relaxation

- Slow down your breathing. Give yourself permission to relax. Focus your attention on your body. If your mind wanders, bring it back to the muscle group you are working on at that moment.

- Breathe in slowly, then breathe out slowly. With each breath out, imagine you are releasing tension.

- Tense or tighten each muscle group in turn. Make sure you feel the muscles tighten, but do not tense so much that it causes you pain. Keep the muscles tensed for about 5 seconds.

- Release or relax the muscles and stay relaxed for about 10 seconds.

- Continue to the next muscle group.

- After going through all the muscle groups, take a few moments to breathe deeply before you return to activity.

- Right hand and forearm. Make a fist with your right hand.

- Right upper arm. Bring your right forearm up to your shoulder to “make a muscle”.

- Left hand and forearm. Repeat as for right hand and forearm.

- Left upper arm Repeat as for right upper arm.

- Forehead. Raise your eyebrows as high as they will go, as though you were surprised by something.

- Eyes and cheeks. Squeeze your eyes tight shut.

- Mouth and jaw. Open your mouth as wide as you can, as you might when you are yawning.

- Neck. Be careful as you tense these muscles. Face forward and then pull your head back slowly, as though you are looking up to the ceiling.

- Shoulders. Tense the muscles in your shoulders as you bring your shoulders up towards your ears.

- Shoulder blades/Back. Push your shoulder blades back, trying to almost touch them together, so that your chest is pushed forward.

- Chest and stomach. Breathe in deeply, filling up your lungs and chest with air.

- Hips and buttocks. Squeeze your buttock muscles.

- Right upper leg. Tighten your right thigh.

- Right lower leg. Do this slowly and carefully to avoid cramps. Pull your toes towards you to stretch the calf muscle.

- Right foot. Curl your toes downwards.

- Left upper leg. Repeat as for right upper leg.

- Left lower leg. Repeat as for right lower leg.

- Left foot. Repeat as for right foot.

Take a few minutes to practice this technique now.

-

Knowledge Check: Psychosocial Needs (5 min)

-

Reading: Key Points (5 min)

Here are some key points from this module.

- There are three components to immediate care for a survivor of GBV: attending to safety needs, attending to physical medical needs, and attending to psychological needs.

- Safety needs include assessment of suicide risk and immediate safety planning.

- Survivors who have prior suicide attempts, detailed plans or ideas, underlying mental health issues, and/or access to the means to commit suicide are considered high risk for suicide and need immediate care.

- Safety planning consists of determining that the survivor has a safe place to go and has strategies to find safety if they are in an unsafe situation.

- Physical medical needs include physical examination and forensic specimen collection, prevention of unwanted pregnancy, and prophylaxis and treatment for HIV and other STIs.

- Termination of pregnancy is legal up to 20 weeks in documented cases of rape.

- Emergency contraception and PEP are most effective when administered or started within 72 hours of a sexual assault, but can be given up to 120 hours after the assault.

- Psychological needs include planning for social support and identifying short- and medium-term coping skills.

- Addressing the need for coping skills can focus on the survivor’s existing strengths and skills.

- Breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation are two techniques for reducing stress and anxiety that can be taught within a short clinical visit.

-

References

- 1South Africa National Contraception Clinical Guidelines, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- 2South Africa National Contraception Clinical Guidelines, 2012.

- 3 South Africa National Sexually Transmitted Infections Management Guidelines, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2018.

- 4Guidelines and Standards for the provision of support to rape survivors in the acute stage of trauma, NACOSA, 2015. Access February 27, 2018.

- 5 Decker, S.E.; Naugle, A.E. (2008). "DBT for Sexual Abuse Survivors: Current Status and Future Directions" (PDF). Journal of behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim: Treatment and Prevention. 1 (4): 52–69.

- 6Center for Clinical Interventions, North Metropolitan Health Services in Western Australia. Access February 27, 2018.

- 7World Health Organization, 2014. Health care for woman subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: A Clinical Handbook, field-testing version.