“Just imagine it: your parents on their hands and knees groping at a swarm of crickets unleashed from an upturned box; your teenage sister screaming at toads spawning in the bath; squirting cucumbers launching a raid of missiles down the stairs; and the gut-wrenching stench of a freshly unfurled dragon arum wafting through the front door. This is what I subjected my family to” (p. 7).

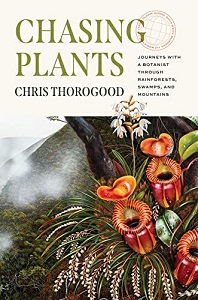

This opening paragraph, recalling the author’s childhood love of living things, lures the reader into the text. Chris Thorogood is Deputy Director and Head of Science at the Oxford University Botanic Garden. He is also a fine botanical illustrator and a winsome writing stylist. This volume focuses on his pursuit of rare plants, developed from his own diaries. The seven trips described take the reader from England to as far as South Africa and Borneo. (No searches in the Americas.) Each chapter includes one or more oil paintings of the sought-after plants.

In Kent he scrambles over the edge of the White Cliffs of Dover to collect picris broomrape

(Orobanche picridis). Impressively, he sits on a foot-wide shelf, “examining, measuring, collecting and scribbling,” (p. 29) and twisting to take a photograph. He then makes it back to the top of the cliff, fending off repeated efforts by a huge gull to pluck him from his perch.

On the Golan Heights near Israel's northeastern border, he avoids a mine field to reach the black iris

(Iris atrofusca), pausing to consider its beauty in spite of its absence of color.

In Japan, at the Botanic Gardens of Toyama, his guide, the Curator of the Gardens, begins the tour singing a Japanese folk song, accompanied by his shamisen, a three-stringed instrument. One plant there,

Monotropastrum humile, “a leafless, ghostly white plant, each stem supporting a nodding flower that looks strangely like a pony’s head” (p. 172), gains attention because Japanese scientists had recently discovered that its seeds are spread by cockroaches.

Thorogood’s variety of experiences and his skill in delivering them combine to make

Chasing Plants a very entertaining read.