|

|

|

|

The Pantheon |

|

written

by asc1 / 09.08.2004 |

|

|

| |

Description |

| |

| |

|

| http://www.niu.edu/cseas/outreach/SacredArchi.htm |

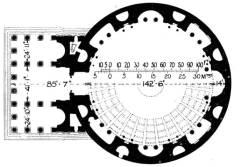

| Floor Plan of the Pantheon |

| The pattern on the floor consists of squares and circles and symbolizes order within the Roman empire. A 19th century reproduction of the original floor exists in the Pantheon today. |

| |

|

| |

|

| http://www.arch.montana.edu/classes/Foreign%20Studies/fall2003/3x3x3/Italy_Images.htm |

| Pantheon Exterior |

| Standing outside the Pantheon, observers can gain a sense of the large scale of the building.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| http://www.arch.montana.edu/classes/Foreign%20Studies/fall2003/3x3x3/Italy_Images.htm |

| Pantheon Interior |

| The oculus serves as the main source of light inside the Pantheon. |

| |

|

The image of the Pantheon is a sight that no one can easily forget. On the exterior, the scale of the building dwarfs all who stand before it. On the interior lies a sight that few are prepared for.

Having been built between 118-128 AD, the Pantheon possesses architectural features that were popular during its construction, while also maintaining its own uniqueness. The porch and the intermediate block assume a Greek style, with an entablature resting on sixteen columns. After passing through the portico, one encounters the large rotunda that follows a Roman style because the large dome is supported by exerting strain on the walls of the cylinder on which it rests. The particular design of the Pantheon, including the unification of Greek and Roman style, has led to speculation as to who the architect of the Pantheon was. While conclusive evidence of the identity of the architect has yet to be found, some believe Hadrian might have designed the entire building. Hadrian had a strong interest in architecture, and had a love for both Greek and Roman culture. Thus, the Pantheon symbolizes his attempt to combine both cultures’ architectural styles in one building.

The building of the Pantheon would have been a huge undertaking. In total, five thousand tons of concrete were used to build the rotunda by pouring successive rings of concrete into a previously constructed wooden framework. The walls of the cylinder were six meters wide to support the strain of the entire dome on the foundation. The height and diameter of the interior rotunda both measure 43.3 m; the implication of this is that a perfect sphere with a same diameter would fit just perfectly inside the rotunda. The oculus, or opening at the top of the dome, measures 8.8 m across and significantly lightens the load on the foundation of the structure. It is also in keeping with the belief that there should not be a roof on a Roman temple. Serving as the major source of light in the Pantheon, the oculus also allows in rain and snow, setting a different atmosphere throughout the seasons. The floor is sloped towards drains that are present to collect rain. Blind windows line the rotunda, probably meant to let light into the extensive network of passageways that are used by maintenance crews. William MacDonald, a Pantheon expert, believes that the windows also allow the building to breathe by circulating air to prevent moisture collection that could cause cracks in the cast cement. The marble work on the floor containing patterns of circles and squares is a 19th century accurate reproduction of the original floor.

When observing the Pantheon from outside, the columns play a significant role in adding to the grandeur. The sixteen monolithic columns are made of red and gray granite and the shafts stand 40 Roman feet tall. Carved in eastern Egypt, the transport of the columns to the construction site required them to be floated up the Nile River on a barge, through Mediterranean Sea and up the Tiber River. Once they reached Rome, they were carried down the streets of the city and then erected. Three of the columns on the east side of the building fell, and were replaced by the Pope Urban VIII and Alexander VII. The columns of the Pantheon have prompted a lot of discussion because scholars believe that if the columns had only been 10 Roman feet taller, they would have allowed for continuity between the porch and intermediate block that is lacking in the current structure. Certainly 50 Roman foot monolithic columns were considerably more difficult to acquire; it is quite possible that the larger columns were instead used for the Temple of Trajan, which was being built by Hadrian around the same time for his adoptive father. Problems with obtaining larger columns may have thus prompted the architect of the Pantheon to compromise and use smaller columns. Politically, it would have been important for Hadrian to devote the larger columns to the Temple of Trajan to show respect for Trajan, especially because the size of the columns was very important to the Temple of Trajan since it dictated the size of the entire building, whereas it was not as crucial to the structure of the Pantheon.

When it was first built, the entire exterior of the dome, as well as the interior of the coffered ceiling, would have been covered in bronze. However, some of the bronze was removed to make the 80 cannons at Castel Sant’Angelo, Hadrian’s mausoleum, but was eventually returned when it was melted down for the tomb of Vittorio Emanuele II, which now rests at the Pantheon. Some more of the bronze was pilfered by the Goths, but most of it was taken by the Barberini Pope Urban VIII, prompting the expression “what the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.”

Many aspects of the exterior as evident today would have been very different when the Pantheon was first built. The brickwork covering the outer wall of the rotunda would have been covered in stucco, marble paneling, or even travertine. Currently, the Pantheon sits somewhat sunken into the floor because the street level has risen around the building. Originally, the Pantheon would have sat high above street level, with five steep stairs used to reach it.

Since it was rededicated as a church, the Pantheon houses a collection of religious art and several tombs. Upon entering the rotunda, the first chapel to the right is a fresco of The Annunciation, attributed to Melozzo da Forli or Antoniazzo Romano, and two 17th century angel statues flank the fresco. In the aedicule is a 14th century fresco of The Coronation of the Virgin. The second chapel contains the tomb of the first king of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele II. In the main apse is an icon of The Virgin and Child, dating from the 7th century. The tomb of the artist Raphael also lies in the Pantheon, as requested by Raphael when he studied the Pantheon during his report on the state of monuments, after he was appointed to serve as the superintendent of antiquities in 1515. Other artists buried in the Pantheon include Giovanni da Udine, Perino del Vaga, Taddeo Zuccari, Annibale Carraci, and Baldasare Peruzzi. The niches contain statues of various saints and priests.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|