|

|

|

|

Enter into the underground... |

|

written

by calaroni / 09.08.2004 |

|

|

| |

Description |

| |

| |

|

|

| The Entrance into the Catacomb of Priscilla |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Enter into the underground... |

| The entrance into one of the galleries |

| |

|

| |

|

|

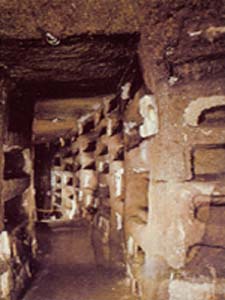

| A gallery within the catacombs |

| Look closely to see the hollowed-out niches in the walls of the gallery. These are the loculi. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

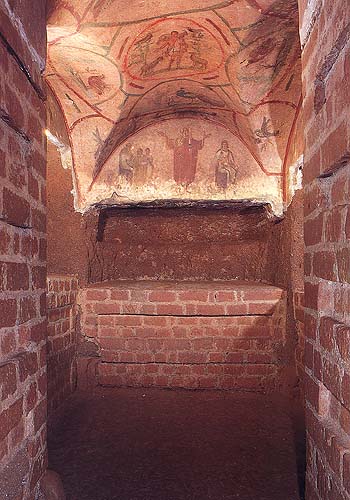

| The Cubicle of the Good Shepherd and the Velata |

| The Good Shepherd is at the very top of the photo, the Valata, a woman with outstretched arms, is in the middle of the photo beneath the Good Shepherd. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| The Velata, up close and personal |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Good Shepherd close-up, 3rd Century |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| 'Virgin and Christ Child and Prophet' |

| The first known image of the Madonna |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| The Greek Chapel |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| The Banquet Scene of the 'Fractio Panis,' the Breaking of the Bread |

| late 2nd century |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| The Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace |

|

| |

|

The Catacombs:

Early Christians knew catacombs as coemeteria – places of repose – originating from the Latin expression ad Catacumbas. This in turn comes from the Greek phrase kata kumbas, “at the hollows,” a suitable expression for underground cemeteries.

The early Christians, just as their pagan predecessors, regarded the burial of the dead as a tremendously important deed. Originally, when there were few Christians, the burial of Christians took place in pagan cemeteries. Later on, Christian cemeteries were constructed on the properties of prominent and wealthy Christians, or land offered by other wealthy Romans. In the beginning of the second century, due to grants and donations, Christians began to bury their dead underground. Many of the catacombs started and developed near family tombs, whose newly-converted owners but opened them to their fellow Christians. Burials were often performed by family members and servants, but as the numbers of Christians increased, burials were hired out to professionals called fossores, or diggers. Fossores performed many tasks, from the preparation of surface graves to the excavation and decoration of the catacombs. Early in the third century, the Church took charge over the burial places of Rome.

Aboveground cemeteries were also popular during this time in Rome, but for many reasons, Christians preferred underground cemeteries. Mostly, Christians preferred burial because Christ was buried, as opposed to the pagan ritual of cremation which they felt disrespected the dead. As Christians grew in numbers, the space available for aboveground burial would have been quickly exhausted if they had not used the catacombs since Christians did not own enough land for all of the burials. The catacombs were the solution to this problem. They were economical, safe and practical. It turned out to be cheaper to dig underground than to buy large pieces of land in the open. As the early Christians were predominantly poor, this was the solution to their problems. Other such reasons for burying their dead underground in tombs were influenced by the sense of community felt by the Christians. In the catacombs, they felt they could be together even in the “sleep of death.” Not only were the catacombs used as burial grounds, they were well-suited for community meetings and “free displaying of Christian symbols” as they were out-of-the-way places, especially during the Christian persecutions.

Near the year AD 150, hundreds of years of development began on the long series of Christian catacombs. This idea of an underground tomb chamber was not necessarily unique, as such chambers had been constructed years before. Other such catacombs had been constructed long before, in the fourth and third centuries BC, by non-Christians in Anzio and in North Africa.

During the construction of the Christian catacombs, Roman law forbade the burial of the dead within the city walls. Because of this, all catacombs are located beyond the city walls.

Physical description:

The catacombs are a series of underground tunnels that form a labyrinth that can reach several miles. The galleries of the Catacomb of Priscilla reach 13 kilometers. Catacomb galleries were cut into rows of narrow rectangular tombs, called ‘loculi’, of different sizes, each of which could hold one body. Sometimes, though, the remains of more than one body were found in one. The bodies were wrapped in a sheet, in imitation of Christ, and placed in the loculi. The loculi were then sealed with a slab of marble, tiles, or terracotta slabs. Most of these seals have disintegrated by present day. On the seal, sometimes the name of the deceased was engraved along with a Christian symbol. Between the loculi, one can see the small holes that held oil lamps that illuminated the gallery and perfume vases.

In addition to the loculi, other types of tombs were used in the catacombs: the arcosolium, the sarcophagus, the forma, the cubicula, and the crypt. The arcosolium, used in the third and forth centuries, was a larger tomb than the loculi and had an arch above it. The tomb covering was placed horizontally and was often used as the burial chamber for families. A sarcophagus is an inscripted stone or marble coffin. The forma is a tomb dug into the floor, commonly used near the martyrs’ tombs. The cubicula, meaning ‘bedrooms’, were small rooms with several loculi, used as family tombs. The cubicles and the arcosoliums were often adorned with frescoes of biblical scenes and themes of Baptism, Eucharist and Resurrection. The crypt is a larger room used as martyrs’ tombs and underground churches decorated with paintings and mosaics.

The fossores, gravediggers, dug each gallery by the dim light of lamps and used baskets and bags to haul the dirt away. The lucemaria, meaning ‘skylights’, were shafts that reached the surface opened in the vaults of crypts and cubicles. They were used to pass dirt out of the catacomb and served as a vent for air and light into the catacomb.

The Catacomb of Priscilla:

The Catacomb of Priscilla is one of the smaller catacombs of Rome, located beneath a villa once owned by the ancient Roman family Arcili, a family of which Saint Priscilla was once a member. Many popes were buried in the Catacomb of Priscilla because the catacombs of Saint Callistus were full.

The Cubicle of the Velata in the Catacomb of Priscilla is named after the fresco on the central wall depicting a woman in a tunic and veiled head with her arms outstretched in a prayer. On either side of this fresco are scenes showing significant moments in the life of the deceased. In the crown of the cubicle is a fresco of the Good Shepherd. This mid-third century painting depicts one of the most common themes in early Christian art: the Shepherd carrying a sheep. This theme arises from John 10:1-21, Luke 15:1-7 and 11-32. The shepherd is said to represent Jesus’ loving search for each child of God. In the depiction of the Good Shepherd in the Catacomb of Priscilla, the Shepherd holds a lost sheep upon his shoulders as two other sheep look on. This figure is part of a larger fresco of praying figures and the story of Jonah and the Whale.

Dating back to the third century, a fresco in a gallery in the Catacomb of Priscilla depicts the oldest known image of the Madonna. On the ceiling of the gallery, one can see another Good Shepherd, a symbol of Christ amongst trees. At the far right of this is an image of the Madonna and Child with a prophet pointing. Resources disagree as to what the prophet is pointing to; some say an apple in a tree, some say a star. The star is considered an allusion to the prophecy of Balaam: “A star shall come forth out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel” (Num 24:15-17). Those who say the prophet points to an apple say that the apples in the tree are in the placement of the stars on Jesus’ birth and that the specific apple to which the prophet points is the Star of David.

The Greek Chapel, a Pompeian-style decorated chamber, has a unique architectural plan with three niches for sarcophagi and a long bench for visitors along the left wall. Many scenes depict themes from Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, along with Greco-roman mythology, that allude to the resurrection and immortality of the soul. Such symbols include the Phoenix and the personification of the four seasons. In the far arch of the chamber, one can see the Fractio Panis, ‘the Breaking of the Bread’. On the opposite side of the arch is Jesus calling Lazarus out from the tomb. Other symbols, like Noah and Moses, depict salvation through baptism, and others, like Daniel in the Lion’s Den and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, depict salvation through divine intervention.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|