|

|

|

|

Aqueducts and the Trevi Fountain |

|

written

by floods / 09.13.2004 |

|

|

| |

Introduction |

| |

| |

|

| www.xenohistorian.faithweb.com |

| Romulus & Remus |

| The myth of Romulus, founder of Rome, and Remus, his twin brother, explains that the two were raised by a she-wolf after being left to drown in the Tiber River. |

| |

|

| |

|

| www.iath.virginia.edu |

| Acqua Vergine |

| The Acqua Vergine, which supplies water to the Trevi Fountain, is almost entirely underground. |

| |

|

| |

|

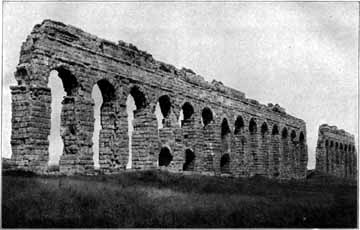

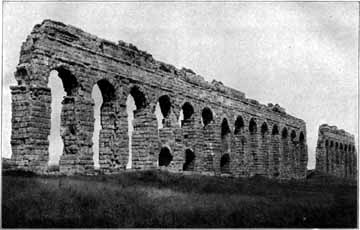

| http://en.wikipedia.org |

| Acqua Claudia |

| The Acqua Claudia is the largest remaining aqueduct that can be seen above ground. |

| |

|

| |

|

| www.thais.it |

| Trevi Fountain |

| The Trevi Fountain, designed by the little-known poet and architect Nicola Salvi, was completed in 1762 by other sculptors, after his death. |

| |

|

The Role of Water in Ancient Rome

Rome was indebted to water from the day it became a city, when the mythological founder Romulus purposely selected an area traversed by the Tiber River and rich with flowing springs. The area was especially worthy because it was where he and his twin brother Remus had supposedly been set adrift to drown. Since then, water has found a place in mythology, religion, medicine, wealth, and of course, in practical purposes (however exaggerated). Elements of water in the form of rivers, floods, springs, fountains, and playful water nymphs are a crucial part of Rome’s foundation story and mythology.

Water was also used early on as a healing agent. Ancient Romans once even used water as a form of medicine. There are legends of the prophetic water nymphs of Camenae and the healing Spring of Juterna. Ironically, today it is speculated that the “healing waters of the Tiber floods” actually caused widespread plagues.

In addition to healing purposes, water rose as a symbol of great wealth and power. Romans began building structures employing water obsessively. It functioned as a necessary component of private status symbols such as fountains, baths, and villas, as well as a tool of political propaganda, power status, and the empire’s largesse. In fact, speculation suggests that water functioned as an agent of wealth and luxury rather than for strict hygiene or health purposes: “[…] Water supply in the Roman city […] has little or nothing to do with the promotion of public health and hygiene, and we may muddy the waters, so to speak, if we insist that it did” (Koloski-Ostrow).

Because water was considered public property and open for people to infinitely consume and enjoy in whatever form they desired (from the most elaborate fountains to the simplest indulgences), town governments avoided the expense of purchasing private land for aqueducts by seizing and zoning public land. Aqueducts were constructed as a result of the growing need for more and more water, and a more indulgent relationship with water ensued.

Engineering of An Aqueduct

Given the cultural significance of water, there was a growing demand for water suppliers. Aqueducts, which allow for the efficient passage of water through a pipe and out a given destination, were constructed in order to meet the desires of the ancient Romans. The first aqueducts supplied water for large public baths, private villas of emperors, and decorative fountains, both public and private.

Considering the time period and the advanced capabilities of the aqueducts, the skill of ancient engineers is easily recognizable. The system worked on an extremely huge scale, yet most of the aqueducts were remarkably uniform. High and low extremes of each aqueduct were impressively similar to one another. This was due to the tendency of large aqueducts to impede traffic. Instead of constructing large aqueducts in areas requiring more water, the ancient Romans simply added more “regulation” aqueducts.

There were, however, several flaws in the aqueduct systems. For example, many of the aqueducts leaked and needed frequent repair. Being continuously exposed to weather, falling subject to the typically hard water of Rome, and withstanding constant use, they often required maintenance. In later centuries, popes would restore ancient aqueducts or build completely new ones. Additionally, most of the original structures were constructed using lead pipes, now known to be hazardous. The system itself and the sheer volume of water consumed was remarkable for the time period. The engineering exemplified the Roman ideals of luxurious water use and symbolized the grandiosity of the empire.

Water flow through ancient aqueducts could be achieved in two ways. The first was a pressurized system using enclosed pipes which were completely filled with water. The system allowed for water to be carried down and up again. The second method, which was characteristic of Rome’s ancient aqueducts, employed gravity through the use of free-flow channels. These channels, which were big enough to accommodate a grown man, tunneled underground and through the mountains, into hill contours or constructs in buildings. The pipes were never completely full of water; it passed gradually downward until it met its destination in the form of baths, basins, fountains, or water displays.

Famous Aqueducts in History

The first aqueduct in Rome was the Acqua Appia, built in 312 B.C.E. by Appius Claudius, and stretching 16 km in length. The Acqua Appia entered Rome where Porta Maggiore now exists, and provided water for the roughly 200,000 inhabitants of the city. As the population increased, demand for water and structures using water also rose, which led to the eventual construction of ten aqueducts during the Republic and Empire.

Among these constructions was the Anio Vetus, the oldest aqueduct in the Park of Seven Aqueducts, which was mostly underground and built between 272 and 269 B.C.E. Other functioning aqueducts were the Acqua Marcia in 44 B.C.E., the Acqua Tepula in 125 B.C.E., the Acqua Julia in 33 B.C.E., and the Acqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which were initiated by Caligula in 38 A.D. and restored by Vespasian in 71 and Titus in 81. The aqueducts pulled water into Rome from far outside of the city walls, the largest at the time being Anio Novus at 95 km long and 28 m high. By 52 A.D., there were nine aqueducts in use, supplying Rome with almost 1000 liters of water every day. Considering the Roman population of one million, this number earned Rome the title of the only city in the world ever to be supplied with so much water.

The last aqueduct built in ancient Rome was completed by Alexander Severus in 226. In 537, the aqueducts were cut off by the Goths, but regained popularity in the 16th century, when popes began to restore and rebuild them. The papal aqueducts Acqua Felice, Acqua Traiana, Acqua Paola, and Pia Marcia, still function in modern Rome. The most recent papal aqueduct, Pia Marcia, which was partly constructed of cast-iron, was inaugurated by Pius X in 1870, a mere ten days before Italian troops put an end to the papal rule in Rome.

After 1870, the water supply was increased again and again to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population. Acqua Vergine Nuova was inaugurated in 1937, and the most recent aqueduct was constructed between 1938 and 1980. This aqueduct, Peschiera-Capore, is the largest aqueduct using only spring water in the world, currently providing more water to Rome than all of the other aqueducts combined.

Today the oldest surviving aqueduct is the Anio Vetus (built in the third century B.C.E.), but it exists almost entirely underground. The most noticeable aqueduct is Acqua Claudia, whose high arches stretch far above street level.

The Story of the Trevi Fountain

The Trevi Fountain is the most famous fountain in Rome, its name deriving from the words tre vie (meaning three roads), referring to the roads that converged where the fountain now stands. It was conceived by Pietro da Cortona and Bernini, but due to the death of Pope Urban VIII, the fountain was not completed until 100 years later, when Clement XII held a competition for the design. The little-known architect and poet Nicola Salvi was granted the commission, and the fountain was finished between 1732 and 1751. Nine sculptors and a number of stonecutters worked on the fountain until its completion.

The Trevi draws water from the Acqua Vergine Antica aqueduct, which is almost entirely underground. This aqueduct was brought to Rome by Agrippa from a spring roughly 20 km east of the city, in order to supply water to his public baths by the Pantheon in 19 B.C.E. The aqueduct was restored in 1570 by Pius V, after years of use throughout the Middle ages, and still feeds the fountains of Piazza Farnese, Piazza di Spagna, and Piazza Navona.

Salvi’s design incorporates a background composed entirely of the Neo-classical façade of Palazzo Poli, which had been completed in 1730. The fountain itself was finished in 1762, after Salvi’s death, and restored for the first time from 1989-1991.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|