|

|

|

|

Fascism and The Via Dei Fori Imperiali |

|

written

by joelnish / 09.18.2005 |

|

|

| |

Description |

| |

| |

|

| Imago Mundi, Vol. 51 (1999), 152 |

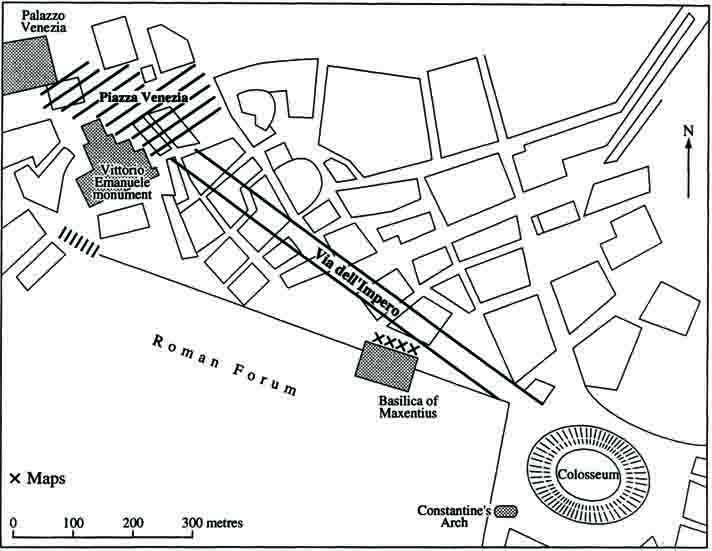

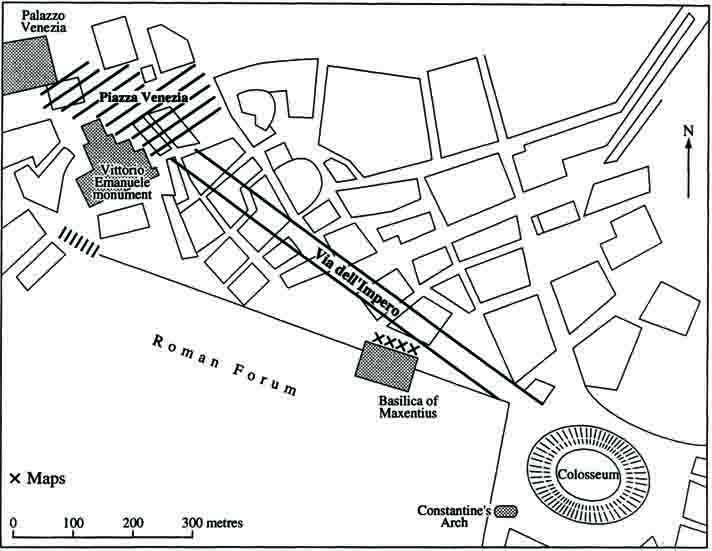

| Road Plan |

| The design of the Via dell'Impero called for the destruction of an existing sector of the city. |

| |

|

| |

|

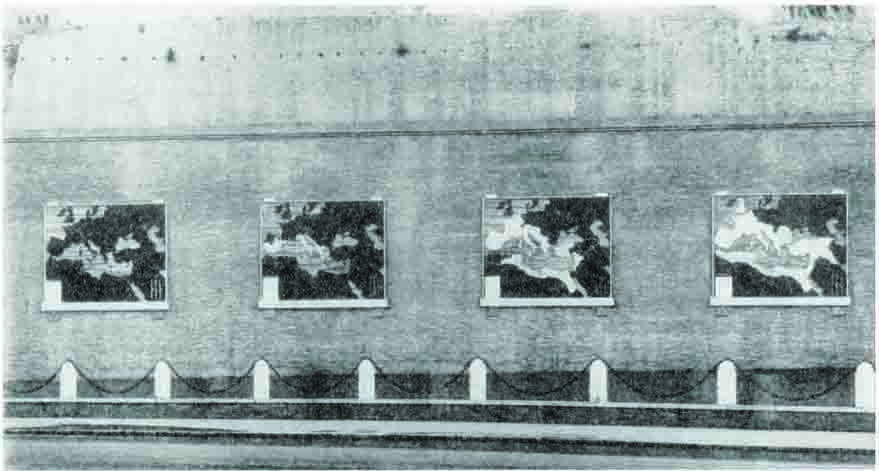

| Imago Mundi, Vol. 51 (1999), 148 |

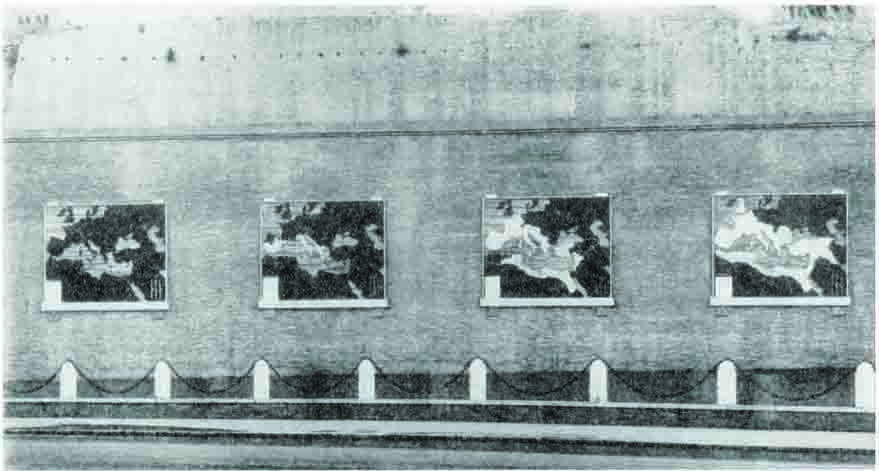

| The Four Maps |

| These four marble maps are placed at the base of the Basilica of Constantine and depict the expansion of the Roman Empire. |

| |

|

| |

|

| Imago Mundi, Vol. 51 (1999), 155 |

| The Fifth Map |

| This map was added in 1935 to glorify Mussolini's African expansion but was taken down later after his fall. |

| |

|

| |

|

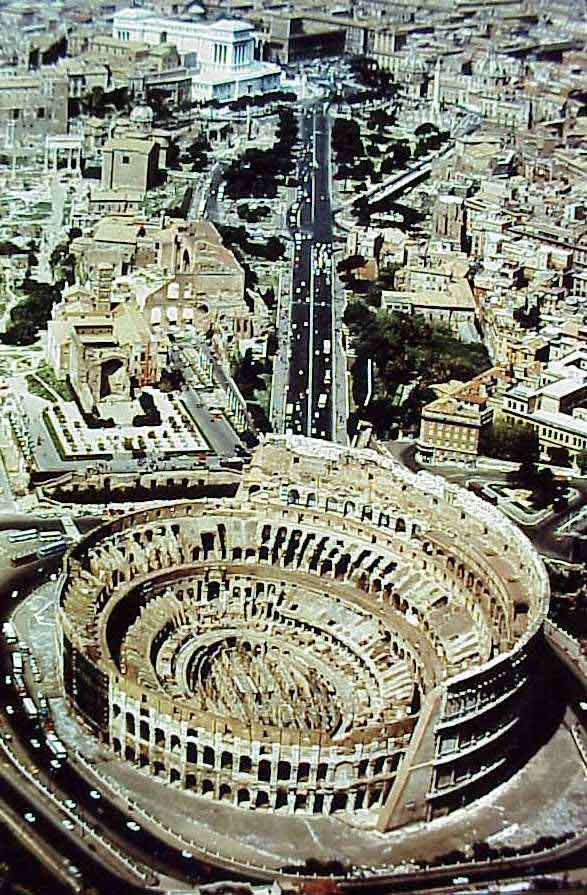

| http://faculty-web.at.northwestern.edu/art-history/werckmeister/May_4_1999/902.jpg |

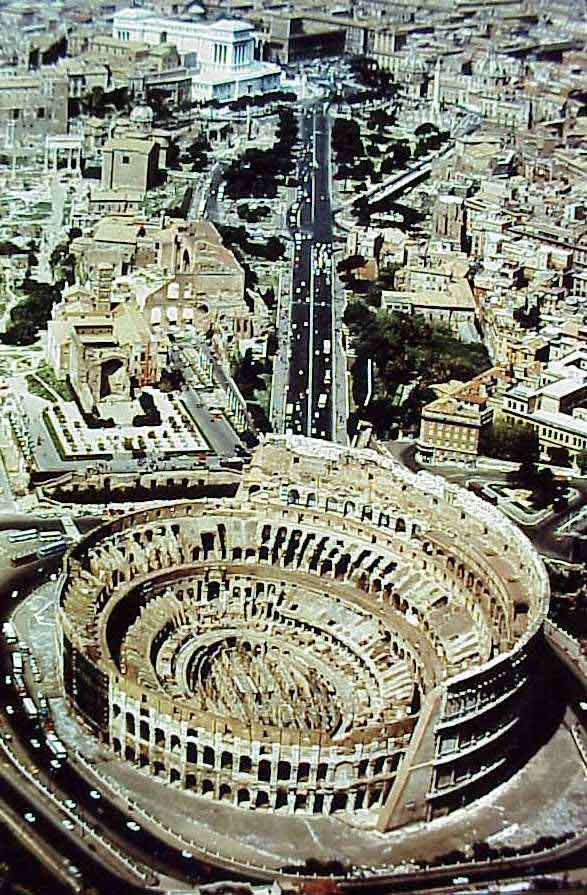

| The Via dell'Impero |

| The Via dell'Impero links the colosseum to Piazza Venuzia through the heart of Ancient Rome. |

| |

|

A large four lane Avenue with wide sidewalks the via dei Fori Imperiali begins at the Piazza Venezia and leads to the Colosseum. Along the way the via dei fori Imperiali cuts a large swath through the center of ancient Rome, dividing the Forums of Trajan and Augustus from the Roman Forum and Caesar’s Forum and covering the Forums of Nerva and Vespavian. This provides for an incredible view of the most important sights in ancient Rome. Not only are the forums clearly visible but the Palentine also rises in the distance, displaying the home of the Roman Emperors. Additionally the giant Basilica Constantine shadows the road. The road also is linked to Mussolini’s Fascist government because the road starts at the piazza Venezia, where Mussolini had his office moved to in 1929. In fact this piazza was the location of many of Mussolini’s most significant political speeches and was symbolically the center of Fascist power.

On the sides of the road stand large bronze statues of the most famous Roman emperors. The bases of these statues are inscribed with the names of the Emperors, the letters S.P.Q.R, and a declaration that they were produced during the tenth year of the Fascist rule. Further along the road there are a series of four large marble maps, displaying the expanse of the Roman Empire in white, un-Roman land as black, and the sea as grey. The first map displays a single white dot symbolizing the city of Rome before any expansion. The second map displays the size of the empire after the Punic wars, while the third and fourth maps are of the empire at Augustus’s death and during the reign of Trajan respectively. These maps were added in 1934, two years after the opening of the road. A fifth map was also added in 1935 but was later taken down after World War II. This map displayed the expanse of the Italian empire under Mussolini, highlighting the expansion into Ethiopia. The original location of this map is still evident though from the coloration of the brick that it originally covered.

The road was constructed in just eleven months, at breakneck speeds in order to be completed in time for the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome. The construction of this road was a major undertaking, as it demanded the destruction of much of the Pantani sector of the city. In many cases the tops of buildings were simply lopped off and the basements filled when the road was built. In total five ancient churches were dismantled and several large tenements were destroyed, displaying thousands.

To the modern visitor it is a frustrating contraption, providing an annoying artificial barrier that fills the air with soot and noise. The pure practicality of the road destroys whatever hopes there is of unifying ancient Rome into a single ancient park. In the words of the urban planning critic Henry Hope Reed:

As one of the most ambitious of Mussolini’s attempts to re-create in Rome the city of the ancients, it is only fair to the planners to say that the Dictator traced the line of it himself, and boasted that it was constructed at his will. The only comment worth making on this carefully and extensively laid-out waste is that, with its concrete paths leading nowhere and its municipal lamp standards lighting up nothing, it is the most symbolic and fitting memorial to a dictatorship in existence.

Yet during the Fascist regime the road held a deep symbolic meaning, physically linking Mussolini’s government with the ruins of ancient Rome. By exploring the fascist use and intention of the via dell’Impero we will in fact explore the pathos behind the appeal of the Fascist movement.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|