|

|

|

|

Divine Nepotism |

|

written

by lmschultz / 08.01.2005 |

|

|

| |

Introduction |

| |

| |

|

|

| Fig. 1 |

| Maffeo Barberini, Urban VIII |

| |

|

| |

|

|

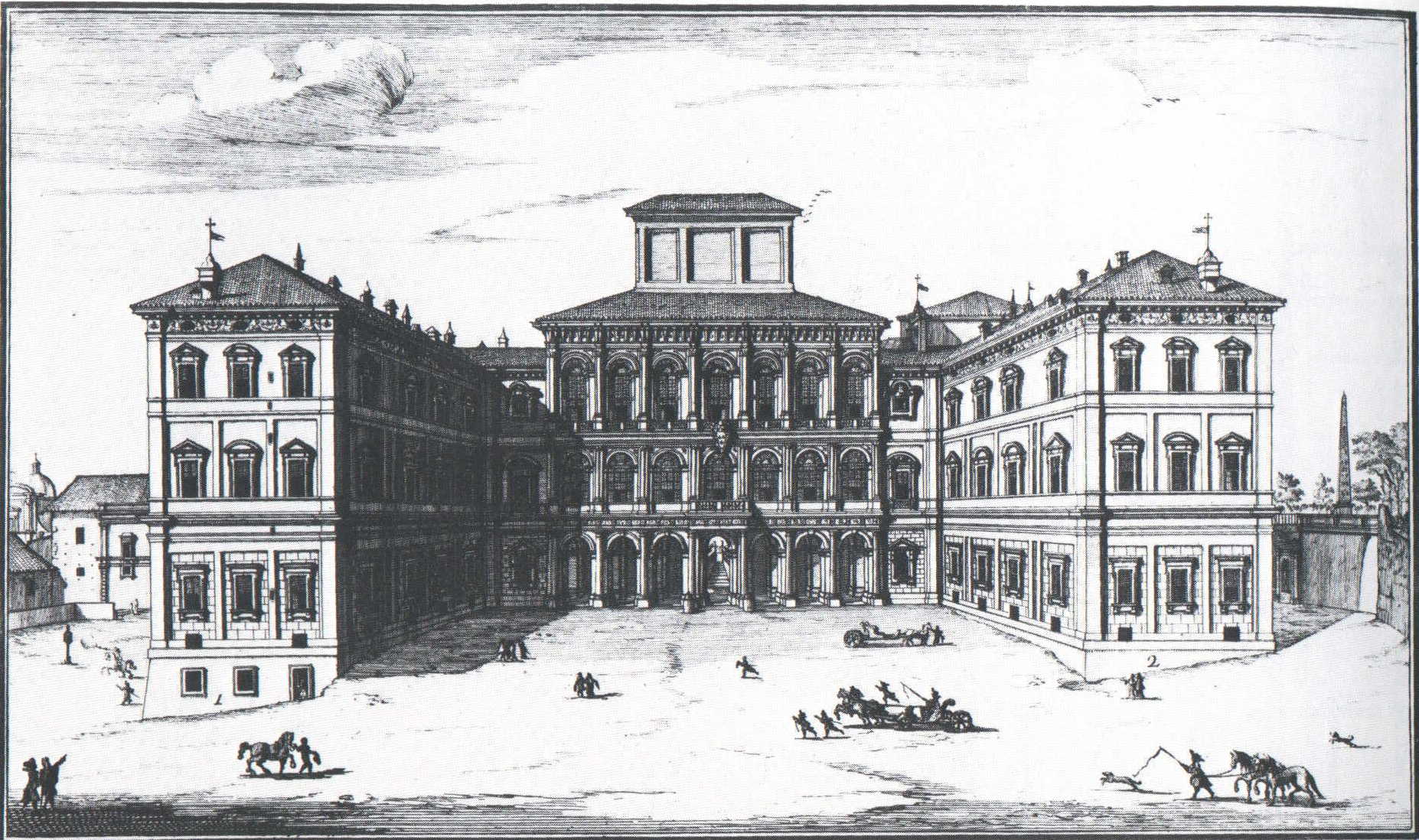

| Fig. 2 |

| Palazzo Barberini, engraving by Specchi, 1699 |

| |

|

The reign of Urban VIII had arguably the greatest impact on the artistic and cultural climate of seventeenth-century Rome. A published poet and already a major patron as cardinal, Maffeo Barberini’s rise to the papacy thrilled the Italian intellectual establishment. During his twenty-one year pontificate he created an unsurpassed model of magnificent patronage, spending lavishly on beautifying Rome. With a similar spending zeal Urban, like many popes before him, strove to enrich and empower his family. But despite the worldly splendor his patronage brought the Roman populace, when word of Urban’s death spread to the city there was jubilation. Criticism was aimed primarily at the many honors, offices, properties and unspeakable wealth the pope had indulged upon his three nephews. Elected to the papacy from relative obscurity, Urban had gone to considerable expense to persuade the Roman nobility of the God-given right of his family’s newly elevated status. Finding the triumphant exuberance and celestial illusionism of baroque art and architecture the perfect vehicle for expressing this message, Urban spared no expense in employing the greatest artists, architects and sculptors to decorate the family’s grand new palace on the Quirinal Hill. Palazzo Barberini thus became the ultimate tool of propaganda, artfully conveying the political and social agenda of the family.

Acclaimed art historian Rudolf Wittkower states in his Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750, Pietro da Cortona is the third name of the great trio of Roman High Baroque artists, along with Bernini and Borromini, yet his contribution remains less well known than the other two. Cortona was by far the most influential painter in all of Italy in his day with large frescos constituting the basis for his highly successful career. The seventeenth century was the great age of the painted ceiling and Cortona contributed significantly to this phenomenon. His stylistic synthesis and mastery of visual language appealed to both popes and monarchs eager to express their elevated positions and ideologies. He was called upon by several of the most powerful and influential families in Italy, eager to decorate newly purchased or renovated palaces with monumental, elaborate frescos praising the virtues associated with their highly esteemed family name. The Barberini brought in Pietro da Cortona to decorate their new palazzo, ultimately leading to his coveted commission in 1632 for the great ceiling of the Salone.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Description |

| |

| |

|

|

| Fig. 3 |

| Divine Providence, Pietro da Cortona, fresco, Palazzo Barberini. Oblique-angle view from ideal station point. |

| |

|

The Grand Salone of the Palazzo Barberini has been called one of the most brilliant creations of Roman Baroque art. But what makes it so? Rather than develop any new radical techniques, principal innovations of Cortona’s fresco derive from a synthesis of three distinct traditions of illusionistic ceiling painting: the Roman tradition of fictive entablatures and faux materials, the Lombard-Emilian tradition of figures overlapping feigned architecture and the Venetian effect of the illusionistic vertical plane of figures.

The shear size of the Salone alone is unprecedented. Not since the decoration of the Sala Clementina in the Vatican (1597-98) had a ceiling of similar dimensions been painted. In true quadratura paintings, such as the Sala Clementina or those in the Casino Ludovisi, the fictive architecture expands the vertical space of the room continuing the structure lines of the actual walls into imaginary space. Cortona’s painted framework follows the surface of the actual vault rather than breaking through it. The illusionistic architecture does not violate the architectonic integrity of the vault. Instead the framework serves to define the physical surface of the vault. Cortona first considered a system of quadri riportati inspired by the Farnese Gallery. He rejected this standard Mannerist solution in favor of a traditional Roman device, popular throughout the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, a fictive framework that divides the vault into five sections. But instead of using three-dimensional stucco, Cortona used paint to create the effect. The delicate gilt and white stucco decoration, which provides the transition between the painted vault and the walls of the salone, is one of Cortona’s early ventures into this medium, which he was soon to develop to new heights. The framework enables the viewer to perceive both the illusionist widening and illusionist contraction of space. An open sky behind the scene in each field unites the unlimited space beyond the frame. At the same time figures and clouds superimposed on the frame seem to hover within the vault in the viewer’s space. This double illusionism has a long tradition with Lombard and Emilian painters, exemplified in the work of Mantegna and Correggio.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Function |

| |

| |

|

|

| Fig. 4 |

| Detail of Divine Providence, central narrative |

| |

|

The central grouping in the Barberini ceiling illustrates the lessons Cortona’s learned from Veronese’s Triumph of Venice in the Doge’s Palace. In addition to addressing spatial solutions and grouping of figures, the way the illusionism takes effect in the Venetian painting, inspired Cortona. When observed from the ideal station point the figural plane tilts forward and the figures seem to rise. This is quite different from the static, geometric groupings popular in Renaissance period ceilings. The Barberini figures are dynamic, in a state of evolution as if they might disappear any moment. From directly below, where many photographs of ceilings are taken, this entire effect is lost. Cortona takes into account the points of entry into the salone and bases his illusionism around these key points. From the correct viewing point all of the rhythm and energy lead the viewer’s eye toward the principal subject matter in the central panel. In addition to the central panel, the images that most project into the viewer’s plane are those which represent positive moral virtues: Minerva, Moral Knowledge and Dignity, the theological virtues and the animals denoting the cardinal virtues. Cortona uses illusionism not only as a formal devise to bedazzle but also to send a subtle moral message to the viewer.

To better understand the complex program of the ceiling one must first look to the patron who commissioned the work. Urban VIII came from a relatively obscure background. His family became wealthy in the wool trade in Tuscany but their holdings and social standing were relatively modest by Roman standards. The papal electoral system followed the belief that the hand of God controlled the proceedings and no matter how mysterious the outcome, the final choice was a matter of divine election. Thus, when Maffeo Barberini unexpectedly became Pope, with all the wealth from the income of the Papal States at his family’s disposal, he faced immediate resistance from the older and established papal families in Rome. It therefore became necessary for the Barberini to convince the world of the God-given nature of their good fortune.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Patron |

| |

| |

|

|

| Fig. 5 |

| Minerva Overcoming the Giants. This portion of the narrative program represents the battle between the church and heresy. |

| |

|

Cortona’s success is distinguished by the way he applied this synthesis of traditions to organize composition of the largest scale and greatest complexity. The frescos in the Barberini indicate important innovations in a conceptual context as well. The design and decoration of the ceiling reflect the combined secular and ecclesiastical aspirations of the family. Cardinal Francesco Barberini, lived in the palace with his younger brother Taddeo. Taddeo had been chosen from among the Pope’s nephews to carry on the family name. These two brothers, one with secular ambitions as the Prefect of Rome, one with ecclesiastical ambitions as a Cardinal, were the most immediately involved with the design of the palace. The north wing of the palace contained the apartments of the secular arm of the family while the new south wing housed the ecclesiastical members. The Salone served the two wings in common and just as the palace consists of two groups of apartments, so is the imagery of the ceiling painting divided according to this distinction. The divine mission of the papacy, represented by the scene of Minerva overcoming the Giants echoes the battle between the church and heresy. The worldly mission of the papacy, personified by Hercules overcoming the harpies, represents the virtuous church’s battle over vice.

The original program, designed by poet Francesco Bracciolini, is a combination of elements taken from the Old and New Testaments, from mythology and from ancient and modern history. Unlike the formal prototypes for the ceiling, the iconographic tradition from which the salone fresco derives is entirely Roman in character. The Sala Clementina and Sala di Constantino in the Vatican palace provided inspiration for Christian images and personifications associated with papal aspiration. The Galleria Farnese provided iconography of the aspirations and virtues of their family. A combination of papal and familial traditions was found in Vasari’s Sala di Cento Giorni in the Palazzo della Chancelleria. The Barberini fresco surpasses these prototypes in the degree to which it depicts the origin, means and ends of those virtues. It illustrates the ideal papal virtues operative under Urban’s reign and confirms for the viewer that these same virtues make the Barberini pope worthy of election and guarantee his immortality.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Conclusion |

| |

Pietro da Cortona’s skill as a painter, architect and designer made him sought after, above all others, by the most powerful families in Italy. Each had a specific message they wanted to promote to the world about the place of their respective family names in the course of history. The more established the family dynasty, the more self-aggrandizing the scheme. As his fame spread across Italy, Cortona was able to consistently improve upon himself, creating innovative programs befitting the glorified expectations of his patrons and developing a macchina that would inspire artists for generations.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Personal Observations |

| |

The first time I saw this ceiling in person, I was an undergraduate student particpating in an art history seminar in Rome. I was amazed by the enormity of the fresco and the vibrancy of the colors, the complexity of the iconography and illusionism. In addition, I was facinated by the intrigue and drama surrounding the Barberini family at this particular moment in time. For some reason I felt a connection with their Palazzo and I felt that my future would involve spending more time there. Before long I had turned my academic focus toward 17th century Roman ceiling painting. I returned to Rome several times and visited Palazzo Barberini often. As luck would have it I discovered a painting in the Palazzo that had been neglected by art historians and scholars over the centuries. It would become the topic of my Masters thesis. Amazing what effect the Cortona fresco really had!

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Bibliography |

| |

Hall, James. Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art. Oxford: Westview Press, 1974.

Paul, C. “Pietro da Cortona and the invention of the macchina”, Storia dell’arte, v.89, 1997.

Sjostrom, Ingrid. Quadratura, Studies in Italian Ceiling Painting. Stockholm, Sweden: Almquist and Wiksell International, 1978.

Scott, John Beldon. Images of Nepotism: The Painted Ceilings of the Palazzo Barberini. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Waddy, P. Seventeenth-Century Roman Palaces: Use and the Art of the Plan, New York and Cambridge, Mass, 1990, pp. 57058, 199-200.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|