|

|

|

|

Hadrian's Villa: A Roman Masterpiece |

|

written

by somers / 10.04.2004 |

|

|

| |

Introduction |

| |

| |

|

|

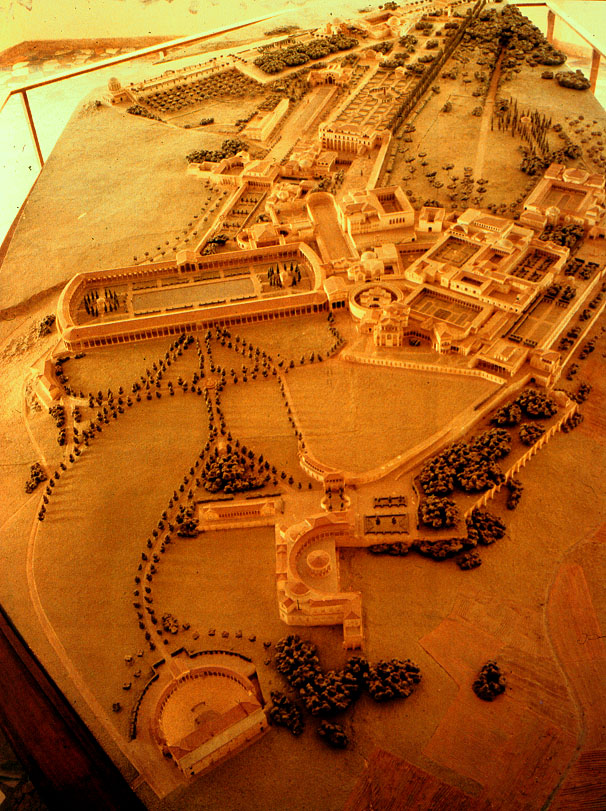

| Hadrian's Villa |

| Here's a model of the grounds. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

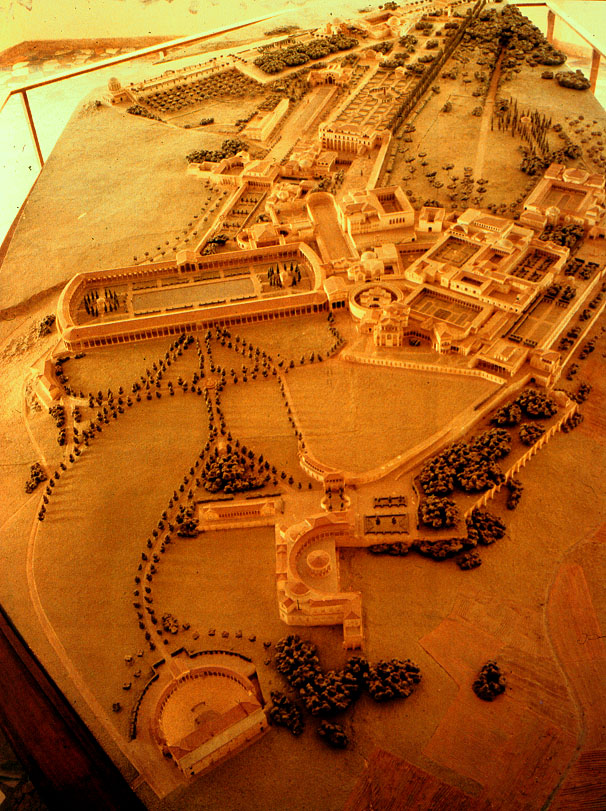

| Publius Aulius Hadrianus |

| Here is a marble bust of Emperor Hadrian. |

| |

|

Set among the rolling hills in the countryside of Campagna, Hadrian’s Villa graces an area larger than Pompeii with its many pools, baths, fountains and majestic classical architecture. The Villa’s chief architect, the Emperor himself, reinvented the idea of classical Greek architecture in Roman society. But before we examine the scope of Hadrian’s influence we must first become familiar with Rome and her faithful Emperor, Hadrian.

In 117 AD, Rome’s power and grandeur stretched further than ever before. The expansionist emperor Trajan led Roman armies across the Danube in the North and the Euphrates in the East. This is the climax of the Pax Romana, and during these years the Roman Empire enjoyed peace and order throughout its far-reaching states. Innovation and invention were at peak levels with the introduction of new marbles, gems, and other raw materials.

Now enter Emperor Hadrian, a successful army general, learned scholar and philosopher. As commander of the Eastern Army, he came to power after the son-less and dying Trajan adopted him. Though controversy predictably erupted among senators, it was quelled by Hadrian’s unanimous military support and fear of civil war.

Born Publius Aelius Hadrianus in AD 76, Hadrian quickly showed an aptitude for academics. He had an incredible memory that allowed him to learn geometry, arithmetic, literature and art at their highest levels. He had a fascination with all things Greek and was said to speak Greek more fluently than Latin, and in some cases demanded that his servants speak in Greek. Said to write speeches for Trajan, he was an eloquent and convincing speaker trained in the art of rhetoric – a quality that brought him success and political influence.

As Emperor, Hadrian spent almost half of his reign travelling the empire. From Britain to Syria, from Athens to Alexandria he founded cities, built roads and temples, erected monuments and heard the concerns Roman populace. This was tremendously important for our purposes. These travels shaped the way Hadrian wanted his Villa to take form.

In AD 118, building and remodelling began on a Republican Villa thirty kilometres outside Rome. While Hadrian was away, intense construction took place until about AD 125 when he returned. We know Hadrian moved his official residence to the Villa at this time based on letters he wrote, and was there until AD 128 when he left for his second major trip. More building took place once again and the Villa was completed in AD 133 or 134. Hadrian would remain at the Villa until he passed away in AD 138.

The Villa was probably inhabited for some time after Hadrian’s death based on the discovery of portraits of Antoninus Pius (138-161) and Marcus Aurelius (161-180). But sadly, as with many of the ancient Roman ruins, the Villa was quarried for the following fifteen hundred years. The twelfth century church Santo Stefano beyond the Villa’s southern boundary was almost entirely constructed with Villa marble, as was the church of San Pietro in Tivoli. Today almost no original art or statuaries remain, centuries of looting by treasure hunters has scattered it all over the world.

Fifteen hundred years of quarrying and almost two thousand years of weather leave the modern viewer struggling to imagine how Hadrian’s Villa would have stood and functioned. But fortunately for us, modern scholarship and research has been able to recreate an accurate picture of this ingenious Emperor’s awesome Villa.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|