|

|

|

|

The Pantheon |

|

written

by zinnia / 09.04.2005 |

|

|

| |

Description |

| |

| |

|

| http://www.danheller.com/images/Italy/

Rome/Landmarks/Slideshow/img13.html |

| The Oculus |

| The Pantheon has an opening, the oculus, that is the only source of light entering into the temple |

| |

|

| |

|

|

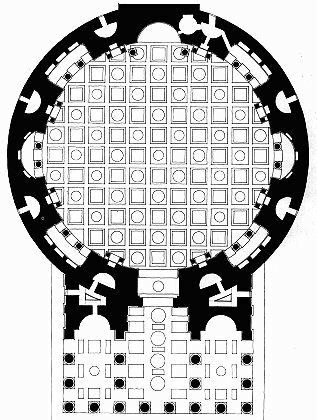

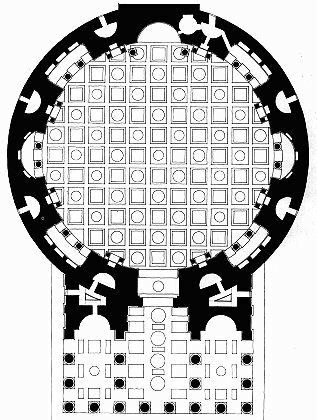

| Architectural Plan of the Pantheon |

| http://www.romeguide.it/MONUM/AR

CHEOL/pantheon/the_pantheon.htm |

| |

|

| |

|

| http://forum.aceboard.net/5397-1479-49870-0-Pantheon-Domaine-Bleu.htm |

| Interior Painting |

| Painted by Giovanni Panini, the painting illustrates the interior of the Pantheon in the 18th century. |

| |

|

The splendor and longevity of the Pantheon never ceases to fill those that gaze upon it with awe; as Michelangelo acclaimed it as “angelic and not of human design”. Erect and completed in less than ten years, it has withstood ravages by both men and nature for nearly two millennia and continuing. Although the building’s survival owes a fair amount to its reconsecration as Santa Maria ad Martyres, the ingenious design and lasting materials nevertheless plays an important role. Made of pozzolana cement (mixture of lime and volcanic ash from Pozzuoli, Italy), the Pantheon is entirely concrete without any steel underpinning. The pronaos and connector have rectangular trenches as their foundation; a circular foundation measuring 7.3m wide and 4.5m deep is laid for the rotunda.

Originally, five marble steps led from the square in front of the Pantheon onto the entrance portico, so that the building ascended to a podium and orientation was given to the rotunda; the concepts of orientation and landscape were traditional in Roman design. Over the years, as nearby archcitecture fell to ruins, the Pantheon’s surrounding ground level rose and buried the steps. The portico also has 16 Corinthian granite columns supporting a gable-styled roof. Measuring exactly 40 feet (12.2m) in height, each monolithic shaft (part of the column, 48 feet) weighs 60 tons and was made and shipped from Mons Claudianus in Egypt. The majority of transportation back then was done via water route, which was efficient, albeit very costly. They were transported to the Nile River on sledges and then boated to Alexandria. There they crossed the Mediterranean to the port of Ostia and barged down the Tiber River. This façade effectively conceals, but not completely blocks from sight, the grandiose dome behind.

Through the 6.4m double bronze doors one enters the rotunda. Still the grandest in Rome, the dome is made of an immense cylinder surmounted by a hemisphere, with an overall inner span of 43.2m and equivalent height that would enclose a perfect sphere. Although now covered with sheets of lead, the dome’s exterior was at first entirely covered with bronze tiles, however it was stripped away in 663 C.E. by emperor Constans II. This dome is made up of superposing masonry masses in concentric tapering steps; heaviest masses (basalt) were used for the 20 feet base and lighter aggregate such as pumice were put on top. This system of design offsets the tendency of the dome to push outward and rupture. In addition, numerous niches honeycomb the cylinder portion of the rotunda, each with relieving arches to divert pressure from the superstructure to eight masonry piers concealed within the circular drum. At the cupola of the rotunda there is an aperture, the oculus, measuring 8.2m in diameter. This circular opening serves as the only source of light into the dome. The oculus also acts as a compression ring that properly distributes compression forces.

Because of its uninterrupted space, a single glance encompasses the entire interior of the Pantheon. Unlike other cathedrals or churches, the inner rotunda is exceptionally simple, with no stairs to climb and no corners to turn. It is precisely because of this simplicity that enables one to perceive of the rotunda’s vast and openness and naturally, be dumbfounded. Along the continuous cylindrical wall there are eight large niches. Directly opposite the entrance is the exedra/main apse, and the remaining six are axisymmetrically situated about the fourfold axis; the six distyled niches are adorned with two marble columns. Also along the curving wall, in between each of the great niches, are eight aediculae (temple-front) with alternating (in twos) triangular and arched pediments. Albeit redone in the 19th century, the paving of the floor is an accurate representation of the Hadrianic original. The floor rises slightly toward the center, patterned into a grid of sizeable squares and circles in squares made of colored marbles, granites, and porphyry; to note is the claret colored porphyry, which back then was the color reserved for royalty.

Triumph of Rome or triumph of compromise? It is unfathomable that even a feat like the Pantheon fails to reach perfection under the scrutiny of modern commentators. Davies’ article brings up several imperfections about the architecture. As it stands today, the Pantheon carries two gabled roofs. The portico has a lower one, one that a normal viewer would see when standing in front, and behind it is the less obvious yet taller pediment of the transition block. In addition, the columns that support the portico seem undersized because of the unusual largeness of the porch’s pediment; their spacing is also more disperse than is usual during the Imperial period. Davies hypothesized that the inconsistencies are due to an abrupt change in design during the midst of construction. The present shafts used for the portico columns differ from what was originally intended. 50 feet shafts (rather than 40 feet) were supposed to be used; this way, the portico would rise to the same height as the transition block with the two roofs merged to become one, thus eliminating the awkwardly dual stacked together. Moreover, the increased height of the shaft would also demand for a base wider in diameter, thereby conforming to the conventional spacing of that time. It is conjectured that the Pantheon settled for smaller columns because of the limited availability of 50 feet columns. With the 10 feet increase in height, each shaft would weigh 100 tons due to the proportional widening of the base; this increased weight would make transportation even more difficult. Alternatively, because the construction of Temple of Trajan occurred in concurrence with the Pantheon, Hadrian may have used the larger monoliths to build the temple, as a gesture of respect to his predecessor.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|