Kenneth B. Pyle is the founding editor of the Journal of Japanese Studies, having served as editor from the Journal‘s inception in 1974 until 1986. In this interview, Pyle shares his perspective on the early years of the Journal and the changes he has observed in the field of Japan studies on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary, as well as insights from his distinguished career as a scholar and mentor of multiple generations of Japan studies students. Pyle was interviewed for JJS by Natalya Rodriguez, a PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The Journal of Japanese Studies provided a vital new venue for publishing research on Japan when it was founded in 1974. From your retrospective on the origins of JJS on the occasion of its fortieth anniversary, it sounds like the stars aligned with the perfect combination of a rapidly growing body of Japan scholarship, generous funding, and a motivated and collegial set of scholars ready to collaborate. To start off, can you tell us a bit about the Journal’s founding?

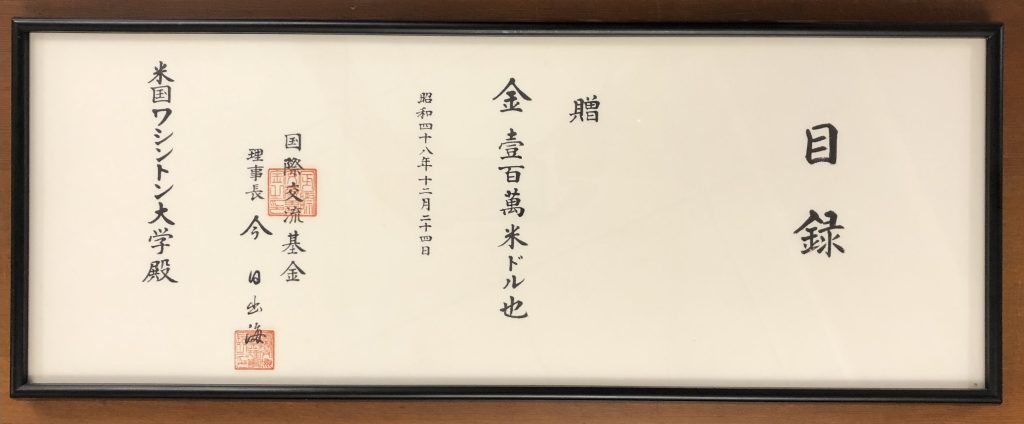

The idea of having a journal was originally mine, but it certainly depended on all kinds of stars being aligned in perfect combination to make it possible. We were very fortunate that we had a group of scholars at the University of Washington in Japan studies who were ready to take on such a project—it absolutely couldn’t have been done without them. And the funding of the Journal was fortuitous because we had just received the one-million-dollar Tanaka grant from the Japan Foundation. This made it possible to launch out into the unknown and see if we could really bring this off. It was a time very different from today for several reasons. One important reason was that the field of Japan studies in 1974 was still fairly small, and Japan studies was taught at relatively few universities.

Your reflections on JJS at 40 note that the Journal was intended to engage scholars around the world from its inception. Looking back after the advent of online subscriptions and instant article access via the internet, this seems like an ambitious endeavor. How did you and the other founders go about building up the international community of contributors and readers of the Journal? What kinds of connections did you draw upon?

The technological changes that we’ve become accustomed to had not taken place yet; it was a totally different environment. If you can imagine, we had to type articles with a typewriter and communicate by letter. Authors wanting to access sources didn’t have anything like e-books to use. Library holdings in Japanese were not yet built up. Archives had to be traveled to rather than going online to read things stored in various archives. If you reflect on the origins of the Journal together with the small number of specialists on Japan, it was a completely different environment from today. With the internet now, you can do so much more and do it faster, without the kinds of problems that I just outlined.

As for building up a network of contributors and readers, another challenge we had was that travel to Japan was a much bigger deal. You didn’t just go over at the drop of a hat and talk to scholars firsthand or have them coming quite so often to this country to engage with. We had to write to the Japanese scholars, sometimes in Japanese, probably more often in English, and wait to have a response from them. That made for a much slower and difficult means of communicating about all aspects of the Journal. Of course, the other editors of the journal and I had our connections to Japan that we could rely on and ask for introductions to other Japanese scholars. So that’s the way we had to start out in the early days.

What lessons can you share based on your experiences for scholars wishing to start or grow a significant project such as a journal?

It’s much easier to do these days. When I think of the confluence of events that made it possible at that time—the grant through the Japan Foundation and the collegiality of scholars at our own University of Washington, it’s hard to imagine younger scholars needing to do all these things. For example, just in the last year or two, a relatively younger group of scholars has started up an online project called MJHA, the Modern Japan History Association. They’re doing this online and exchanging ideas. There are also electronic journals like Japan Focus. It’s so much easier now because you don’t have to rely on such a broad range of factors coming together at the same time.

You mentioned the Tanaka grants administered by the Japan Foundation, which made it possible to establish the Journal of Japanese Studies. Can you tell us more about how the University of Washington was able to get this grant? Did stakeholders at the University of Washington have to advocate for the University to receive the funding?

That’s a really good question. I’ve just been writing up something for the Japan Foundation because of the fiftieth year of its founding, and my understanding and memory of this is that when the Tanaka money was legislated, the Japan Foundation was originally going to give the ten million dollars to Harvard. But those of us at other universities where Japan studies was developed lobbied for a much wider distribution. As it turned out, it really was a wise decision that the Foundation decided in the end to distribute the ten million dollars among ten universities that received the grants. And even later, for example, when Chalmers Johnson was at UCSD, he lobbied for the Japanese government to give his university similar support, and I think MIT did the same thing with Richard Samuels helping out there. In retrospect, I think we convinced the Japanese government to very wisely spread the wealth around.

How did the existence of the Journal impact the field of Japan studies in the Journal‘s early years? Did you see any influence on your own fields of history and international relations?

The initial impact on the field took some time to develop. In fact, we weren’t sure how much demand there really was in the field for another journal. The Journal of Asian Studies was not nearly as comprehensive as it later became, and so scholars published articles quite readily in the Journal of Asian Studies. We weren’t quite sure what was going to happen, and in the very early years we depended heavily on using essays that we ourselves here at UW were working on. We also had to go out and ask scholars to submit anything they might have. You couldn’t just wait to see what came in over the transom in the very early years of the Journal. But over time, as the Journal proved itself and its worth, then of course the submissions came in quite steadily. But those early years really demanded a self-generated effort on our part to start a journal that was of the highest quality.

You spent ten years as the director of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. Did that overlap with your years at JJS?

It did. I was appointed head of what became the Jackson School in 1978, and for the next ten years I was director of the School. Being editor of the Journal and being director of the Jackson School, which is multidisciplinary, I was greatly advantaged in my own scholarship by having to be forced to really understand other disciplines besides my own. Both at the Journal and as director of the School, making decisions about hires and so on, I had to familiarize myself with many disciplines. It did have quite an impact.

You have mentioned in your previous reflections that an important vision for the Journal was to strengthen the long-standing connections among scholars studying Japan. And as you’ve just said, you had important opportunities to engage with multiple disciplines both at JJS and the Jackson School. These days, my impression is that disciplinary affiliation sometimes eclipses scholarly affinity based on a shared topic. What were the benefits of the interdisciplinary dialogue on Japan that you observed? What advice would you offer to scholars who want to facilitate such interdisciplinary discussions?

I think the field itself has become so much more interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary. Scholars now are compelled to go beyond their own discipline to really understand their research projects; thus, scholarship itself has forced change on universities, and I think this is going to go much further. The universities are very slow to change—somebody said it was like moving a graveyard—but it’s tended to be stovepiped, with each department maintaining its own identity and so on. That’s got to change. It’s something we’re going to see, I think inevitably, in the future development of the university.

Sometimes I see what could perhaps be called rivalries between certain disciplines, or simply gaps where one discipline may have different core problems from another discipline. Did you encounter any such gaps that you had to bridge between your own training in history and the work of international relations specialists or other scholars in the School of International Studies? Or was it a pretty good fit from the outset?

My own experience when I was director of the school was that the rivalries tended to be not so much among disciplines, but among regional studies. For example, East Asian Studies had a couple of steps up, and one of the rivalries within the school was with South Asian Studies, and perhaps Southeast Asian Studies as well. Whereas China, Japan, and Russia had early development within many universities, scholars working on South Asia and other parts of Asia felt left behind, and so there were rivalries, you might say, between regional studies more than between disciplines.

I’m sure those developments were heavily influenced by the international context. In fact, you were the editor of the JJS during a very dynamic moment, when all eyes were on Japan’s economic achievements. What was it like to be editor at that time? Did you face any major challenges?

Yes, it was an exciting time, as I look back over 50 years of the Journal and even further back to my own early experiences with Japan, to see where Japan has come from. When I first arrived in Japan it was just a few months after the Anpo—the anti-Security Treaty—riots. At that time, Japan was still recovering from the trauma of World War II. They were still digging up unexploded bombs, and in some neighborhoods you could still see buildings that had not yet been rebuilt from the bombing. So, it was a very different Japan that I came to. In fact, my wife and I sailed to Japan on our first visit. We sailed on a freighter out of San Francisco, nine days on the great circle route up to the Aleutians and then down the coast and arriving in Japan in July 1961. I like to tell my students, partly joking, that the first time they go to Japan they should sail there to get a sense, for historical purposes, of how vast the Pacific is.

Anyway, it was a very different Japan. Then, Japan began to recover and the so-called Japanese miracle took place. We were very fortunate to have Kozo Yamamura on our editorial board at the Journal. Kozo took it upon himself to translate contemporary articles written in Japanese about events and controversies in Japan. While Kozo was so directly involved, that gave the Journal a fascinating contemporary dimension that one could say it hasn’t always had since that time. As Japan became seen as a threat to U.S. industry, things became even more exciting and there were various kinds of debates until the bubble burst and things began to change. Now you even find people wondering whether Japan’s best years are behind it. So, yes, it’s been an amazing vision I’ve had of the evolution of Japan over a long period of time.

I’m also curious, since you mentioned the bubble, whether scholars during that period predicted the sort of economic crisis that would ensue when the bubble burst. Or was it a total shock?

Economics has been a smaller field in Japan studies—really prominent economic specialists on Japan have been comparatively fewer than in other disciplines. But I think economists understood much better than the rest of us how things were getting out of hand. By the time a small bit of Tokyo was seen as more valuable real estate than the state of California, that kind of thing we could understand. But the workings of the Japanese economy were probably only best understood by the economic specialists.

What kinds of changes in the field of Japan Studies did you observe over your years as editor? Did you see any shifts during the seventies and eighties that might be called turns in the field?

One of the things that has happened is the social sciences have become more and more, you might say, scientific in the sense of developing their disciplinary practices, so that you have the economists doing very scientific kinds of analyses, regression analysis and all of the rest of it, which does not translate easily into the broad purview of the Journal of Japanese Studies. You see that particularly in economics, but you see it in the other social sciences too, so the difference between my own discipline and the social sciences has become more and more difficult to bridge. At the same time, other disciplines have developed their own internal controversies and jargon that makes it difficult for those in different disciplines to fully engage with their debates. You might say the extension of the academic world has made it a challenge for the later editors.

My next question shifts to your work as an educator and researcher. Scholars often wear many hats and must balance the responsibilities of each. How did your work with the Journal impact your teaching and research? Were there any unexpected synergies?

Yes. The synergies that I mentioned before of engaging with many disciplines were, of course, reflected in my own writing and in my own teaching, and I certainly welcomed that.

As for the responsibilities of the editor of the journal, Susan Hanley and I, and later John Treat, we had to read all the submissions that came in—that was the job of the editor. I’ve often thought I could have written at least one more book if I hadn’t been editor of the Journal; but I did keep up writing articles during that period of time.

Since you were reading so much of the cutting-edge scholarship, did you feel like you were able to connect your students to the trends and currents in Japan studies?

This was certainly reflected in my lectures and particularly in directing graduate students. I was able to draw on my familiarity with a broad sector of research that I gained through the editorship, which I could then have my graduate students read, particularly in seminars. I could also draw upon this in directing dissertations and MA theses. So, the experience of editing did have that favorable result. I taught at the University of Washington for 56 years before retiring when COVID set in. One of the joys today is having former students come by and visit, which happens quite often; many of them have gone into Japan-related fields and careers, and that’s rewarding to see.

You have mentioned belonging to the first generation of scholars who came to study Japan through primarily academic interest as opposed to prior experience living in Japan or military involvement. What drew you personally to the field of Japan studies?

I grew up in central Pennsylvania, not too far from Gettysburg. My father was on the faculty at Penn State, and I remember him saying to me when I was in my early teens, “Asia is going to be important in your lifetime.” That would have been around the early 1950s, when the Chinese revolution took place, and the Korean War, and so on, and it looked like Asia was going to be a trouble spot. But I think my father was really talking about Asia becoming an economic powerhouse. He was, I think, rather prophetic in seeing the social and economic rise that eventually came about. So, when I got to college, I majored in American diplomatic history, but I began taking courses on Asia at the same time.

Then, in graduate school, I decided that if I was going to be serious about Asia, I had to undertake language studies. Unlike the generation today which starts studying Japanese in high school or maybe even earlier, I started kind of late. So, I went to the Stanford Center—what is today the Inter-University Center (IUC) in Yokohama—and studied there for three years as a graduate student. I felt I had to stay for that length of time to make up for the late start on Japanese language, and I really studied it intensively. In the final year, the Center made it possible for me to study with a very well-known intellectual historian of Japan, Matsumoto Sannosuke, and to audit the seminars of Maruyama Masao, the famous political scientist, and Ienaga Saburō, the famous historian. There was also the unforgettable Tsurumi Kazuko, who was the first woman to receive a PhD in sociology at Princeton. She came from a very famous family, the Tsurumi family, and she was my tutor part of the time at what is now the IUC. So, I had a great experience in those three years.

It was a time when that first, what I call “academic generation” of Japan scholars was arriving in Japan. I was on a Ford Foundation Fellowship and so were Chalmers Johnson and Peter Duus and some other scholars. It was a fairly small group; I would say at the most ten or so. Certainly the Ford Foundation Fellowships were very competitive. In contrast to earlier generations—my professor at Stanford had been in the Occupation and had learned Japanese in the military, and Edwin Reischauer, of course, was from a missionary background—we came to Japan with priority to intellectual questions rather than being in Japan by happenstance. So that was different. To the Japanese we worked with, we were, in retrospect, sui generis in the sense that Americans were coming to study them instead of coming to tell them what they should do. That was a memorable experience, and the Japanese that the IUC hired were particularly keen to take these Americans who were open to learning from Japan under their wing. My own personal tutor would spend 20 hours or more a week with me, taking me off to coffee houses to talk, and to various parts of Japan to see things firsthand. He wasn’t paid for this, but he was motivated by a young American who was coming to study Japan.

I’ve noticed that the kind of hospitality your tutor showed is characteristic of many people in Japan whom I’ve met—what a wonderful experience that must have been as a young scholar. Now, I’d like to bring us to the present moment and your current research. I understand you have a forthcoming book called Hiroshima and the Historians: Debating America’s Most Controversial Decision, which will be published by Cambridge University Press this year. Can you tell us a little bit about this project?

Interestingly, it really grows out of my student years in Japan at the IUC. One of the professors that the Stanford Center hired was a professor of Japanese literature from Waseda, Kawazoe Kunimoto. Kawazoe-sensei took a liking to me, and we became good friends over the years. One day, walking out of class, we were talking about the relations of our two countries when, unexpectedly, he turned to me and said, “Would America have dropped an atomic bomb on Germany?” I was surprised by the question, and it wasn’t something that I had studied, so I could only mumble and answer, “I don’t know.” But he was wondering, as many Japanese have, whether racism had played a part in the decision.

That question stuck with me, and when I became a university professor myself and began teaching Japanese history, I found that the U.S. decision to use the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki sparked an immediate interest with my own students. American students wondered how it is that our country is the only one to have used the bomb on another people. It was something that troubled them. And so, responding to this interest, I decided to start a course, and over a period of close to 30 years, I taught an honors seminar directed to this question of the U.S. decision to use the atomic bomb. It drew a really wonderful group of students. In fact, the competition to get into the seminar was such that I could handpick a really bright group of students, and then, with a seminar size of a dozen or so, we began to look at the literature. There has been an amazing proliferation of writing on this question.

As I introduced the students to the new literature that was coming out, a new question began to spark interest, that is, “How come historians can’t agree on this? Why is there so much dispute over a relatively straightforward set of events and decision making?” And so, very soon this seminar turned into a course on historiography. And the book I’m writing that is coming out in a few months is really as much about the historian’s craft as it is about the Hiroshima decision. Using the Hiroshima decision as an example, I go pretty deeply into the nature of what historians do. I wrote it for a general audience and have tested it on people who are not specialists. They find it quite fascinating because virtually every American has some kind of interest or even opinion about the question; Americans generally are troubled by this. So that’s the way the book evolved over a long period of time.

In one of your talks about historians’ debate over the U.S. decision to use the atomic bomb, you emphasize how contemporary issues shape the kinds of scholarly perspectives that emerge at different moments. How do you view the changes in the field of Japan studies in relation to Japan’s shifting position in international relations?

Unquestionably, the dominant themes in the field have changed over the years. In the early years, when there were just a very small number of scholars working on Japan and everybody pretty much knew everybody else, the questions being asked tended to center more on elite politics and business issues. But then, over time, the attention has turned more to women’s studies and gender studies, for example, and, more recently, popular culture and studying the voiceless, you might say, the people who are ordinarily overlooked by historians. And then even more recently, but on a smaller scale, there’s been development in art history, film, and popular culture.

The Journal of Japanese Studies marks its fiftieth anniversary this year. What are your thoughts on the Journal now, looking at where it has come from and where it is today?

The field of Japan studies continues to evolve. As I think about the future of Japan studies, which I sometimes do, I think technology is going to push us continuously into new issues and new problems. I think AI is going to have its effect on Japan studies and on the Journal, as it’s going to affect everything else in our society in ways that we probably cannot foresee now. I have a friend who is in the corporate leadership of Microsoft, located here in Seattle, who talks about the problems AI will create for things like copyright and so on. To speculate, the Journal will have to be asking contributors to ensure that their writing is entirely original and not derivative from the use of AI. That’s just one example that this friend happened to throw out to me recently. I do think the field is going to be affected and that the Journal will have to deal with some of those issues. AI will impact editing, too. Those are just some thoughts off the top of my head.

The field has grown to such an extent that it is a challenge to keep up with important scholarship. Chalmers Johnson called JJS “the journal of record” for its comprehensive coverage of writing in the field. The book reviews are a valuable service in providing thoughtful critiques by appropriate scholars. Finally, the success of the Journal owes to a lot of people—in particular, the work of Susan Hanley as first managing editor and then editor, John Treat, and subsequent editors. We must especially pay tribute to the dedication of Martha Walsh. For decades, the Journal‘s mainstay has been Martha, a person of almost unbelievable competence, good judgment, and organizational ability.

That’s what I would like to emphasize in closing.

Kenneth B. Pyle is a professor emeritus of History and International Studies at the University of Washington. He was the founding editor of the Journal of Japanese Studies, serving in that position from 1974 to 1986. He has written extensively on Japan, its international relations, and the historian’s craft, including The Making of Modern Japan (1978), The Japanese Question (1992), Japan Rising (2007), and the forthcoming Hiroshima and the Historians (2024). He was a cofounder of the nonpartisan think tank, the National Bureau of Asian Research. Pyle has been honored by the Japanese government with the Order of the Rising Sun, and he received the Japan Foundation’s Special Prize in Japanese Studies in 2008.

Natalya Rodriguez, a PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, uses ethnography to understand how people use cloth and dress as tools for identity formation, political advocacy, social power, and economic revitalization in contemporary Japan and its diasporas. Her past work examined how Japanese kimono enthusiasts in Chicago negotiate the meanings of the garment amid the international circulation of competing kimono images and discourses. Her current project explores women weavers’ efforts to sustain their cultural heritage through the production of traditional textiles in Okinawa.

This interview was made possible by financial support from the Japan Foundation, New York.