“The school is more than just a school for trade union members. It is intended to become a broad community project for the benefit of all people”

-Labor School Executive Director Harry Fugl. [1]

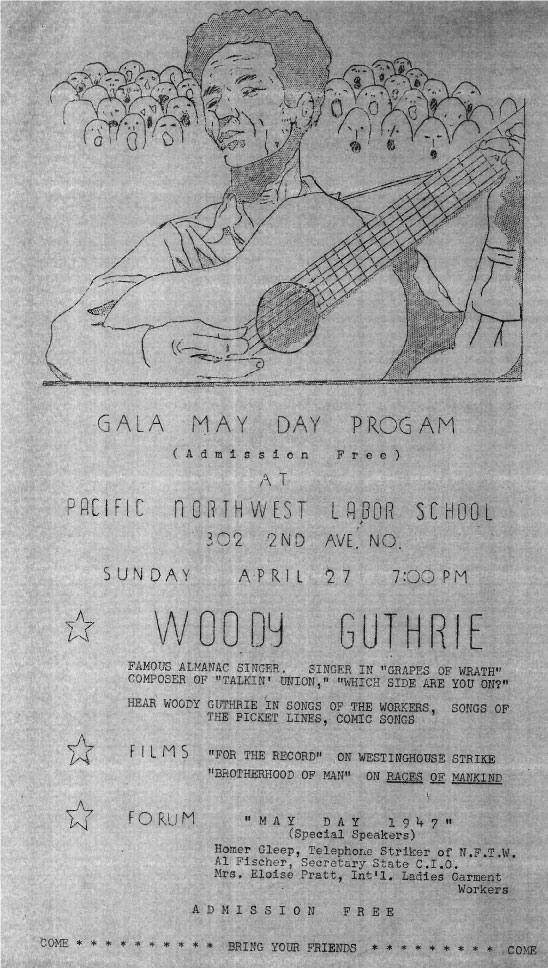

Promotional poster for the Pacific Northwest Labor College

The short lived Pacific Northwest Labor School marks a significant contribution to the history of the region’s labor movement. An important part of a labor’s post-war high water mark, the School was guided by a vision to both develop practical organizing skills and spread labor politics throughout the region. It brought together union leadership, rank and file members, University of Washington academics, and community and religious organizers to promote labor and develop the intellectual skills of movement participants. The School was part of a wave of labor schools that started with the California Labor School in San Francisco in 1942 and spread to New York, Boston, Chicago and Seattle. The Seattle School quickly became a focal point for those interested in building the labor movement in the Pacific Northwest. Yet just as quickly it developed as a lightning rod for attacks from the right, and in the increasingly suspicious and vitriolic anti-communist political environment of the late 1940s it struggled to maintain political and financial support. Founded in 1946, the School folded by 1949. However in that short time the Labor School helped develop an active, educated rank and file that long outlasted the school itself. Its legacy also provides important lessons about the necessity of political solidarity and the problems of sectarian divisions within the labor movement.

The Seattle Labor School’s doors opened as the “Iron Curtain” fell, ushering in a wave of anti-communist rhetoric and paranoia that seriously undermined Seattle’s history of community action.. During the 1930’s and early 1940’s, the local Communist Party enjoyed broad influence in the upper echelons of the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Washington Pension Union, two successful coalition fronts. The WCF and WPU played crucial roles in Seattle’s civil rights scene, the former as a democratic caucus group, the latter as an advocacy group for pensioners and underprivileged children. Though branded as “Popular Fronts” by detractors, both groups mobilized a wide spectrum of supporters and represented serious lobbying power. After World War II and Churchill’s emphatic warning that an “Iron Curtain” had descended across Europe, the global political climate underwent a drastic change. In Seattle communists found old partners suddenly reticent to pursue previously common goals. Old coalitions failed to command cooperation and the political atmosphere became increasingly hostile for communists.

Dr. Ralph Gundlach in 1940As early as December of 1944 Professor Ralph Gundlach of the Psychology department at the University of Washington started to pay attention to the pressing needs of the local labor movement. Having been in contact with labor schools around the country, Gundlach envisioned the school as “a central source of fertile suggestions and materials for …every union,” a community “center that can serve as an agency for calling together different trade union groups, for their mutual cooperation.”[2] Gundlach, in calling for the formation of a Labor School, was calling for the formation of a cohesive and effective labor movement in Seattle.

At Gundlach’s initiation, on October 6th, 1945 “leading representatives from thirty-two trade unions and sixteen government departments and community organizations conferred at the New Washington Hotel to discuss labor adult education.”[3] Members of the initial conference included: Wayne Dick, Director of Adult Education Seattle Public Schools, Jerry Simpson of the Washington State Labor Bureau, Earl Dome, Director of Adult Education at the Seattle YMCA, Rabbi Franklin Cohn, Rev. Benjamin Davis of Mt Zion Baptist Church, Loyd W. Schram, Director of Adult Ed. University of Wash, and William Pennock of the Washington Pension Union, among others. This broad base included representatives of both CIO and AFL unions, and local socialist, religious and union leadership.

An Executive board was established, with UW Professor Albert Franzke, Adult Ed. Council, Harry Fugl as Director, Paul Manning from the machinists local 79, Merwin Cole from Building Service Employees Local 6, Dr. Raplh Gundlach, Ferd Carlson of Streetcarmen’s Union and Hilde Hanson, Secretary of the Seattle CIO Council.[4] It was a board characterized by heavy union control paired with academic resources, guidance and instruction. At the conference, special emphasis was placed on “orienting new members into the union, integration of returned veterans, leadership and other training for shop stewards and committeemen, programs for primary leadership.”[5] The school was to be non-partisan, with affiliated unions paying $10 a month for a half rate of $3 per class for all members and women’s auxiliaries. [6]

The conference outlined the goals of the fledgling school; “To serve the labor movement and the community in general by helping to build a strong, united, more effective and more socially conscious labor movement [and] helping to strengthen democratic movements [in] general.”[7] With those goals in mind, courses were organized around three objectives.

The first of these is to make trade unionism more effective and includes such subjects as Labor law, Public speaking, Union meeting procedure trade union problems and Labor movements. The second group of objectives, aiming at a higher level of citizenship generally through a better understanding of local, state, national and international problems includes basic economics, facts behind the news , medical care and public health, propaganda and how it works, etc. The third group of courses is set up as activities and is organized into workshops.[8]

Though labor was the primary focus of the School, heavy emphasis was placed on general education as well as fostering a strong sense of community. Professor Gundlach’s initial vision of the school was as “a center that can serve as an agency for calling together different trade union groups, for their mutual cooperation; a center that can serve to call together and sponsor city and community- wide cooperation of labor capital and government in conferences and in forums.”[9] This fostering of unity would be critical in building a cohesive labor movement.

Though the men and women who met at the New Washington Hotel conference included a number of academics and intellectuals, the structure of the proposed school ensured strong union control. The Board of Directors was to be made up of elected union members from all affiliated unions that voted for both the Executive Board, and a “Board of Advisors made up of leaders in education and business in the community and members of the Executive board.”[10]

In a letter sent out to all CIO locals in King County, Executive Secretary Hilda Hanson wrote “the policies and plans adopted at the conference will retain the control of this school in the hands of organized Labor and… designed to benefit working people generally.”[11] Enclosed with the letter were the proposed school constitution, budget plan and first term classes to be voted on by locals. The letter proposed a total of 28 classes ranging from “Income Distribution,” “Public Speaking and Parliamentary Law” to photography workshops. Unions responded enthusiastically; 325 students enrolled for the first quarter, representing fifty- three trade unions. Membership of the affiliated trade unions totaled over thirty-eight thousand people.[12]

It was an ambitious beginning for a School without a building, a paid staff or set curriculum. Undeterred, an enthusiastic Executive Board wrote “Twenty seven – organizations are sponsors of the School: … twenty-one instructors from varied fields of education have volunteered their time in teaching classes. More than seventy- five speakers have volunteered to appear for one session of various symposium classes.”[13] Seattle Public Schools agreed to let the Labor School utilize Central School in the evenings, and the Marine Cooks and Stewards offered use of their hall Monday through Thursday until a permanent School Building was established. Building Service Workers local 6 donated $100 to help fund initial overhead costs and the Aero-Mechanics’ Union Local 751 “pledged to supply the school with office furniture.”[14] Classes began on January 14th, 1946 to mixed reviews.

From the beginning, the Labor School faced political scrutiny and open hostility as the political mood in 1946 turned increasingly conservative. Even among the founders of the School, political differences grew heated. Edith Young, educational Director at the Seattle Art Museum, asked if the Labor School would “please be so kind as to remove my name from the Board of Advisors” two weeks after the school opened.[15] Minutes of the February 14th Advisory Board Meeting reveal both political and personal tensions:

Board member Dr. Loimer “asked if there was any foundation to a public rumor that there is communism being taught at the labor school and that there are communists on the board and that some of the instructors and directors are Communistic…Mr. Gundlach pointed out that the Board has been at pains to be as non- partisan, objective and above board as possible. Mr. Franzke pointed out that we have just won a war against Fascism, together with a great Communist ally-Russia, and that even if there were Communists in the School, it is unimportant… He said that he didn’t know of anyone who is a communist, and that anyone who is easily stampeded will run and if everyone who is mildly liberal is going to run for cover just as soon as such unfounded charges are made they are not seriously interested in a Labor School because such charges must be expected . . . Mr. Adams stated that the minute that either his political beliefs or religious beliefs became a basis for determining whether he is fit to serve on the Advisory Committee, he will resign. Mr. Franzke said that there absolutely could not be partisanship shown in the school. .[16]

Despite the School’s emphatic insistence on non-partisanship, the Republican Searchlight described the school as “a Stalinite front organization… the apparent support of outstanding businessmen, educators and clergy men, many of whom could have no intention of promoting totalitarianism.”[17] The school responded with incredulity when several people “suddenly decide[d] to terminate their membership on our board of Advisors. . . Of those quoted in the press, only one member of the advisory group submitted a letter of resignation to the Director.”[18] Despite attacks, most students in attendance expressed appreciation for the school’s efforts, and quickly became involved in the burgeoning labor left social scene.

Before it changed its name in 1947 the College was known as the Seattle Labor School. This promotional poster emphasizes the practical benefits of its programs

By the beginning of Spring term, the School had a better sense of what its members wanted. Classes included: “Books are Weapons,” “Effective Public Speaking,” “Basic Economy,” “Present Day Trade Union Problems,” “Race, Science and Politics,” “Elementary Photography,” and writing, theater, and dance workshops. “Atoms, Men and Machines” taught by Lewis Fowler of the UW Chemistry department was assumed to have great appeal, but was cut when no more than a handfulof students signed up for the class.[19] The Education Committee of the Advisory board reported, “registration for the first quarter indicates that interest at present is strongest in the field of trade union subjects. The Education Committee takes this as an indication of success. But at the same time, it sees in it a challenge to broaden the school program, and the interest of the students in such a program.”[20] Despite the more academic leanings of the advisory board, control rested firmly in the hands of the very labor minded students. In April the Cannery Workers Local 7 requested a two hour daily course on union leadership. The Labor School Began the course a month later Building Service Local 6 pioneered new membership classes, held monthly for with 150 workers in attendance in June. The Marine Cooks and Stewards sponsored a weekly class on trade union history and problems.[21] Through the resources provided by the Labor School, local unions increased rank and file involvement, making for a highly invested movement.

Professor Ralph Gundlach shifted the ideological underpinnings of the Seattle Labor School from education to agitation. He corresponded regularly with Leo Hubberman, director of the Labor School at Lake Hatzic in Vancouver, B.C. The two of them organized a summer labor camp in Vancouver that many Labor School students attended. For Gundlach, mere education was not enough. He wrote, “Seems to me that the over-all aim of the program should be not so much getting certain facts before the audiences, as changing their perspectives and skills and training them as group leaders… each one of whom can take over and make an area hum.”[22] With a more politically active school in mind, Gundlach proposed the board hire Bert MacLeech as educational director. The Labor School wrote a press release lauding his history in labor education.

After three and a half years active service in the army, Bert MacLeech, active labor man comes to Seattle from Samuel Adams School for Social Studies, Boston, Mass where he was Associate Director… He was active in the Teachers Union (AFL) a delegate to the San Mateo Central Labor Council; elected business agent of ILWU local 1-38 in San Diego and was California State Organizer from 1935- 38 for the American league against War and Fascism. Bert MacLeech was educated at Occidental College … with later graduate work at Harvard, Stanford and Colombia Universities. From 1930-33 he taught in the American College in Sofia, Bulgaria. [23]

In an interview, Mr. MacLeech said ‘labor education is of the utmost importance to the Trade Union movement. Labor faces increasing responsibilities, not only in relation to the immediate economic needs of the workers but to many broad national problems.”[24] Under MacLeech’s leadership, the Labor School began a weekly newspaper, extended union outreach programs and established a local labor history library in the school.[25] MacLeech worked closely with the student council to ensure the needs of students were met. In a letter sent to all staff members, MacLeech wrote, “students brought out certain suggestions which we pass on to you. First, it was the unanimous feeling that outlines of the courses would be most helpful. Second, for the more serious students, reading references would lead to further study and understanding.”[26] For many students, the Labor School represented the first accessible formal education beyond high school. Most were eager to learn.

Fall Term, - classes were held Monday through Thursday in the Marine Cooks and Stewards hall - tried to gear classes towards MCS interests “America in Films, Public Speaking, History of U. S. Trade Unions, and Trade Unions and the Negro Worker”[27] The last class was a series of lectures organized by black Marine Cooks dispatcher Charlie Nichols. MacLeech had initially asked Dean Hart of the Seattle Urban League to organize the lecture series, but Hart was unable due to his schedule.[28] The lectures were well attended, as issues of race in unionism were crucial for the liberal school. The degree of black leadership and use of the school was fairly extraordinary. The two unions most instrumental in the creation of the Labor School, the Marine Cooks and Building Service Workers, were racially integrated with large black membership.

As one of the strongest voices of black unionism in Seattle, Carl Brooks of the Shipscalers had been on the temporary organizing committee for the school, and was one of the more popular teachers. Ted Astly, a student and teacher at the Labor School described Brooks as “A very fine man, modest, intellectual, sort of soft spoken black man whom I grew to admire greatly”[29] Astly taught a course in social psychology at the school, and explained his involvement in the school stemming from interest “in promoting the idea of racial equality…. I was interested in promoting the idea that we needed to have a class struggle kind of unionism rather than business unionism, in other words, the CIO kind of unionism as opposed to the AFL.” He insisted the school had a “good mix of men and women, black and white,” [30] making for a diverse, dynamic, and increasingly liberal student body with expansive goals for the Seattle labor movement.

May Day program featuring Woody Guthrie

1947 began with a focus on developing broader extension and social programs and stabilizing the school financially. After a year of fundraising and Marshall fund money, the School was able to purchase a building to house the formerly migrant School. For $8,500, the School purchased a building on 2nd and Garfield.[31] The School proudly announced “we have some new stationary which reads ‘Pacific Northwest Labor School’—and this signifies that our school is beginning to correspond to the fats of life. The facts of life are that the majority of the working class in Washington outside of Seattle and any real program of workers education must recognize this.”[32] As the School struggled to establish itself as a greater presence in Seattle and extend its reach, Cold War paranoia continued to affect the School. The Executive Board reported winter term, “attendance… is at 88 registered and tuition paid… the experience has indicated that certain regular classes can better be handled in extension service.” [33] More concerning for the board was a “noted lack of attention this quarter to political subjects,” [34] symptomatic of growing political pressure to avoid “communistic” appearances.

As Cold War pressures and falling Seattle enrollment plagued the School, leadership focused increasingly on outlying areas with the Extension program. John Daschbach pioneered extension efforts, bussing up to Sedro Wooly, Bremerton and Bellingham to extend the services of the Labor School to a broader audience. Daschbach felt strongly that “with the huge growth of this trade union movement there has grown also the need of trained leadership . . . Collective bargaining becomes a farce when inexperienced negotiating committees of working men have to meet the highly trained, highly paid specialists of the employers Extension courses.”[35] Daschbach corresponded with locals from Anacortes, Olympia, Enumclaw, Port Angeles and North Bend, facilitating new members classes, access to the Labor School Library and general support.[36] Daschbach felt the extension program was “crippled by lack of a car,”[37] but made his services widely available despite the inconvenience.

In an effort to stabilize the School both socially and financially, 1947 saw an onslaught of fundraisers. Almost every class sponsored a dinner or dance at the school, unions took up collections among members and the School bought a 1947 Nash as grand prize in a year long raffle drive. Sold at one dollar a ticket with a goal of $20,000 over the year, the auto raffle was intended to bolster the coffers of labor education.[38]

Smaller fundraisers created an atmosphere of community and solidarity among Labor School students. Dances and dinners were held weekly and became very popular. Small contributions, $31 from the Shipscalers, $80 from Painter’s Local 300, and “$40 from a Paul Robeson benefit were touted as small victories in the “Labor School News,” the school’s student produced weekly.[39] The paper itself provided an important creative outlet for students with writing and journalism workshops, and provided an arena for political debates. The paper also helped students keep abreast of the barrage of Labor School events. Dance classes made dances ever more popular. A School orchestra was formed and played to great acclaim at the St. Patrick’s Day dance.[40] For students, the Labor School offered more than education, it offered community. Childcare was made available during all evening classes to enable parents to attend. Furthermore, “Children’s workshops” were held from ten to twelve Saturday mornings, a valuable asset for working class families.[41] The combination of education and recreation intersected most drastically in weekly forums hosted by the School

Sunday nights were Forum nights at the Pacific Northwest Labor School. With topics ranging from “the Marshall Plan” to “The Problems of the Negro People: Jobs, Housing, Discrimination,” forums provided a community space for differing opinions. Efforts were made to get opposing viewpoints; for a forum on the Taft- Hartly Act, planners asked to “have different viewpoints covered…AFL, CIO, Independent.”[42] Representatives were invited from the Typists, Machinists and Cannery Workers to deal with contending viewpoints. This effort to fairly represent all opinions was grounded in the schools self-proclaimed non-partisanship. But as Cold War pressures continued to escalate, many unions became increasingly hesitant to affiliate with the Labor School.

Enrollment continued to drop. Ferd Carlson wrote in “The Labor School News,”

Many good trade-unionists fear that by attending the School they will be spoon fed some ideology of which they do not approve . . . while we study all problems and while we insist on the right of every student and every faculty and staff member to his own beliefs and affiliations, the school remains – non partisan . . .The good plain union man, the liberal, the technocrat, or even the communist who wants to fight more effectively for pork chops will find here in the Northwest Labor School the training which will enable him to act more effectively on his problems.[43]

Despite the efforts of students and staff alike, the Cold War politics proved intractable.

In November of 1947 Building Services Employees International local 6 abruptly terminated their relationship with the school in a terse letter announcing withdrawal of all members and financial support. After crucial leadership in the creation of the Labor School and two years of active involvement, the withdrawal of the union was a harsh blow to the School’s political and financial stability. MacLeech wrote back informing the local of an outstanding balance of $40 for two New Member’s classes that had helped “draw new members into active participation into the union community” of local 6.[44] In the ensuing correspondence, MacLeech expressed shock at the legitimacy placed on the testimony of one W.W. Warren who had no affiliation with the school, but incorrectly identified “Bruce Nelson” as a communist and teacher at the school. The intended target was assumed to be Bert Nelson, president of the Seattle CIO council, who had never taught a class at the School. Other accusations were leveled at Carl Brooks, John Daschbach, Harvey Jackins and several other individuals without Labor School affiliations.[45] Despite the incompetence of witnesses, the damage had been done. Two weeks later Local 130-ACE Accounting withdrew from the school.[46] MacLeech appealed to the National Civil Rights Congress to join “in protest against this unwarranted and dangerous step in thought control… earnestly [hoping] that your efforts will have an effect in halting the hysteria that is threatening the fabric of our American Life.”[47] A month later, Labor School teacher, student and organizer Merwin Cole was expelled from his post as Secretary in BSW Local 6 as more conservative members ousted liberal leadership.[48] Local 6’s rejection of the Labor School marked a crucial turning point for the School in the eyes of public opinion. It coincided with the formation of the Canwell Committee.

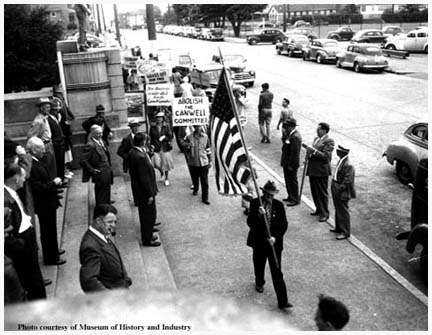

Demonstrators calling for the abolition of the Canwell Committee

Washington State legislation approved the creation of the Canwell Committee at the end of 1947. In calling for its formation, State Representative Albert Canwell argued “persons and groups seek to destroy our liberties and our freedom by force, threats and sabotage, and to subject us to domination of foreign powers.” [49] So began an aggressive investigation of organizations ranging from the Communist Party to the Seattle Repertory Theater, University of Washington and WPU.

The “Seattle Five,” Florence James, Ralph Gundlach, Rachmiel Forschmiedt, Albert Ottenheimer, and Burton James were high profile Seattleites heavily involved in local labor and civil rights work. [I61] Of these five, all but Forschmiedt were present at the initial Labor School Conference in 1945. Both Florence and Burton James as well as Gundlach had taught classes at the Labor School. What was an attack on communist ideology had huge ramifications for the Pacific Northwest Labor School. The School itself was condemned to the subversive lists by U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark on November 24th, 1947.[50] The School refused to quietly accept the charges. The New World reported students and sympathizers creating “a giant telegram declaring the action of Attorney general Clark in naming membership in the Pacific Northwest Labor School as a measuring stick for disloyalty constitutes slander.” [51] 500 signatures were gathered in protest.

Ferd Carlson, teacher, student, songwriter, longtime Forum Committee chair and member of the Streetcar drivers union, embodied the spirit of the School. Frustrated with mounting antagonism toward his beloved school, Carlson wrote a passionate six page letter to President Truman in January of 1948. He wrote, “I, who am not a Communist, nor even a Marxian Socialist, most vigorously deny that I and my colleagues are a front for anything. I was one of the originators of the movement for establishment of such a School, due to my recognition of the need for an education program to strengthen my own union.” Carlson pointed out that the charge of subversion had been leveled at the “Seattle Labor School,” and that the organization with which he had been affiliated had been known as the “Pacific Northwest Labor School” for over a year. He argued that this lack of attention to “public record indicates an unseemly lack of diligence in looking for facts before making such a serious charge.” Carlson’s own union, self described as “a rather conservative organization,” had never felt the school to be “offensive to the most conservative members who have attended.”[52] Carlson signed his letter, “just a bus driver who thinks he’s gotten a dirty deal… yours for democracy.”[53]

Whatever the political affiliation of the Labor School director, direct union involvement created space for the Board of Directors to dictate most School policy in solidly non-partisan way. However, as Cold War pressures mounted and more conservative unions distanced themselves from the School, the nature of the remaining unions became increasingly militant. Only twenty students signed up for Spring term of 1948.[54] Following the abrupt exit of BSU local 6, other unions followed suit.

Largely as a reaction to the Canwell Committee, in early 1948 John Daschbach and other Labor School members founded a Seattle chapter of the Civil Rights Congress to help combat growing cold war attacks on the labor left. A legal front for local Communist Party and labor interests, the Seattle CRC drew heavily on the Washington Pension Union and other Labor School affiliates, becoming one of strongest chapters in the nation. The Seattle CRC combined impressive membership numbers with effective mobilization of that membership, made possible in large part by the training and cohesion offered by the School. [55] At its peak in 1952, the Seattle CRC had 350 dues paying members, 75 of whom were black. The CRC and Labor school shared ideology and leadership, often meeting at the Marine Cooks Hall for fundraisers or forums. Both organizations were highly involved with union locals and the labor school. As the Labor School deteriorated, the Civil Rights Congress facilitated protests of the Canwell Committee, and prioritized legal aid for unions. Daschbach, as acting president of the Seattle CRC continued his Labor School extension programs, expanding the CRC through existing unions and marinating tight contact with unions across the state.

In an effort to redeem labor education from strictly liberal hands, in October of 1948 , the University of Washington offered “Evening Labor Classes” held at the UW Adult Education center. At $8- 12, these classes offered a clearly conservative alternative to the Labor School. Those eligible to attend were “government, labor, and management people.” [56] The University fired Gundlach and other UW faculty who had taught at the Labor School following the Canwell investigations, sparking outrage from academics and civil rights groups across the country.

On April 26th Labor School secretary Merwin Cole received a letter from the Internal Revenue Service accusing the School of tax delinquency.[57] Cole insisted that the school qualified as a non-profit organization. The IRS responded, “The commissioner has ruled that you are not entitled to exemption from Federal income tax … you are, therefore, required to file returns,” threatening the school with a $10,000 fine for “willful refusal to file.”[58] A flurry of harassment from the IRS continued well into July, when the Board of Directors acted to dissolve the school. The School did not officially close its doors until July of 1949, but the there is no record of further courses held after winter of 1948. School equipment - a piano, chairs, a roll-top desk and an office chair - were sold for a sum of $90 as the School hastily disbanded.[59] Over a year later, the $510 left in the Pacific Northwest Labor School account was deeded over to the Seattle CRC “for the defense of local and national civil rights victims.”[60]

In a letter to Eddie Tangen of the Marine Cooks and Stewards, School Secretary Marjorie Wynes wrote; “After a number of years of service to the trade union movement of the Northwest… the board of directors has acted to dissolve the school… we believe that the school made an important contribution to the strengthening of the labor movement by training hundreds of working people and giving them greater understanding of the issues facing the workers.”[61] Though brief, the service provided for the labor community of the Pacific Northwest laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights Congress, developed an active, informed rank and file, and fostered labor cooperation.

[1] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Statement” no date.

[2] Ralph Gundlach Papers. University of Washington Box 3/10. Dec 1 1944: “An Adult Educational School for the Puget Sound Area”

[3] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/11: “History and General Information” Oct. 6 1945

[4] John Daschbach Papers Box 7//25 “Statement, No Date”

[5] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Minutes of Seattle Labor School Conference Afternoon Session October 6, 1945 Windsor Room New Washington Hotel”

[6] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/11 “Proposed By-Laws for the Pacific Northwest Labor School, Inc.”

[7] John Daschbach Papers. Box 6/11 “Statement of Principles of the Pacific Northwest Labor School”

[8] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/27: “Attractive Courses, Outstanding Instructors Featured in Labor School Opening Jan 14”

[9] Ralph Gundlach Papers Box 3/10 “An Adult Educational School for the Puget Sound Area” Dec 1 1944.

[10] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Minutes of Seattle Labor School Conference Afternoon Session October 6, 1945 Windsor Room New Washington Hotel”

[11] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “To All CIO Locals in King County Letter October 15, 1945”

[12] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/11 “Tentative 1946 Budget” This includes all Washington Pension membership, is likely on the higher end of estimates.

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/18 “Letter Jan 29th 1946” From Seattle Art Museum

[16] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/13 “Minutes of the Advisory Board Meeting of the Seattle Labor School Held February 14th 1946 at the YMCA”

[17] Republican Searchlight Vol. 1 No 8 Jan 25th 1946. “Stalinite Octopus Harasses A.F. of L Trade Unionists” by Frank M. Rose pg 1

[18] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/27 “Statement” No Date.

[19] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/27 “Spring Quarter Courses”

[20] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/11 “Tentative 1946 Budget: Education Committee”

[21] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/11 “Statement dated May 20th 1946”

[22] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/5 “Letter August 10 1946 to Bert McLeech from Ralph Gundlach”

[23] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/27 July 29 1946 “For Immediate Release

[24] Ibid

[25] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/27 May 28 1946: “Seattle Labor School ‘For Immediate Release’’

[26] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/5 “Letter sent to all staff. From Bert McLeech” August 22, 1946.

[27] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/5 “Letter September 5 1946”

[28] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/5 “Letter August 9 1946”

[29] Ted Astly Interview. “A History of the Seattle Labor School” written and edited by Robert Olson May 1, 1991 Pg 6.

[30] Ibid

[31] John Daschbach Papers Box 8/6 “Flyer for Spring Term”

[32] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/21 “Extension Courses.”

[33] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Special board meeting Sunday Jan 25 1947”

[34] Ibid.

[35] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Suggested Immediate Program for the Labor Extension Service” Undated.

[36] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/25 “Letter to Mr. George Starkovich September 15, 1947”, “Letter September 19 1947 to I.W.A local 2-198”, “Letter Oct 1 1947 to John Daschbach.”

[37] John Dasbach Papers Box 7/21 “Extension Courses.”

[38] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/16 “Staff Agenda July 29 1947.”

[39] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Labor School News No 4 Feb 25 1947”

[40] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/23 “Labor School News March 17 1947”

[41] John Daschbach Papers. University of Washington Box 7/29 “Labor School News April 28,1947” pg 2

[42] John Daschbach Papers Box 6/17 “January 1948 Forums”

[43] Ibid

[44] Daschbach Papers “Letter December 23 1947 to Mr. Arthur Hare” Box 7/28

[45] Daschbach Papers “Statement by Board of Labor School” Box 7/28

[46] Daschbach Papers “Letter December 5, 1947 to Bert MacLeech” Box 7/28

[47] Daschbach Papers “Letter December 9, 1947 to Mr. Joseph Cadden” Box 7/28

[48] New World December 4, 1947 pg 6

[49] Resolution to the House No. 10.

[50] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/28 “Letter to Eddie Tangen July 7, 1949”

[51] The New World January 15, 1958. “Labor School Blasts Attorney General”

[52] Daschbach Papers “Letter to the President Jan. 7, 1948” Box 7/28

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ted Astly Interview, “A History of the Seattle Labor School “written and edited by Robert Olson May 1, 1991 Pg 12

[55] Horne, G. “Communist Front?” The Civil Rights Congress, 1946- 1956. Rutherford[ N. J.]; London, Cranbury, NJ, Fairleigh Dickeinson University Press; Associated University Presses. (1988). Pg 348

[56] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/31 University of Washington “Evening Labor Classes”

[57] John Daschbach Papers Box D 7/28 “Treasury Department Internal Revenue Service to Merwin Cole April 26th 1948”

[58] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/28“Promissory Note February 1 1948” $500 to Harry Horowitz for attorney’s fees.

[59] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/28 “Receipt July 6, 1949”

[60] John Daschbach Papers Box 7/28 “Statement of the Trustees”

[61] Daschbach Papers Box 7/28 “Letter to Eddie Tangen July 7, 1949”