In 1962, a group of 64 faculty, staff, and students of the University of Washington filed suit to stop enforcement of the university's mandatory loyalty oath, first imposed in 1931. Two years later the Supreme Court ruled with the plaintiffs, setting a precedent for ending loyalty oaths in other states. (Peoples World February 3, 1962) Nineteen-sixty to 1969 was one of the most tumultuous decades in American history. Thanks to television, virtually all Americans could watch the entire decade unfold right before their eyes. From the Bay of Pigs and the Beatles to free love and Vietnam, the 1960s were quite distinct from most eras in American history. Having survived the McCarthy era and the Red Scare, not unscathed but still intact, the Communist Party (CP) began to find itself again during the decade. However, the early Sixties were a rough time for the Party, which had been in something of a lull after the 1950s due both to Khrushchev’s revelations about Stalin and to the relentless pursuit and expulsion of Communists from areas of government and society by HUAC and other government organizations. The Party found ways to stay organized and in touch with events, and, as the decade progressed, became a more open entity. Nevertheless, it was still a persecuted group whose members were often fearful of declaring their Party affiliation. Even so, in Washington State, Party members were active if cautious.

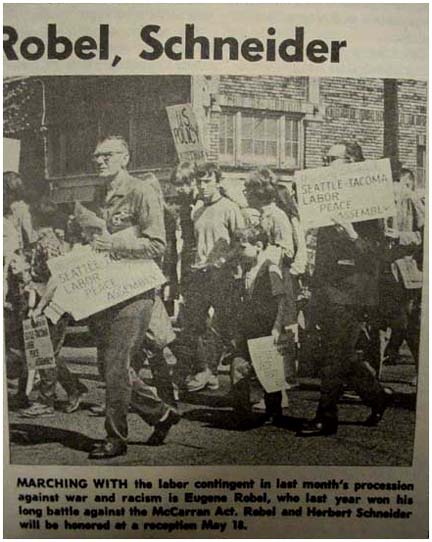

Eugene Robel was arrested in 1963 charged with violating the McCarran Act that made it illegal for a Communist to work in a defense industry. Robel at the time worked for Todd Shipyard. In 1967 the Supreme Court voided that part of the Internal Security Act. (Peoples World May 11, 1968) One of the ways that the Washington State Communist Party began to organize openly was around its newspaper, The People’s World. The paper, in existence since the 1930s, was published in San Francisco, and represented the Communist Party on the West Coast. Washington State Party members—Lonnie Nelson, for one—helped distribute the paper and write for it, as well.[i] The paper was an important vehicle for the WSCP to get its message out. Each year the Party organized picnics to raise money to keep the People’s World in circulation; these gatherings were held in public parks where members and friends of the Communist Party were encouraged to discuss current events and raise money for the paper.[ii] The annual draw to the picnics was anywhere between 75 to 150 people and was considered the big Communist Party event of the year.[iii] Both paper and picnics provided a bonding experience, as well as avenues for recruitment.

This period also marked a new openness for the Communist Party as part of its strategy to break out of isolation. Though still hounded and haunted by anti-communist sentiment, the Party was trying to re-surface to regain a political presence. Nevertheless, very few people put their own names to the articles that they wrote in the PW, and even fewer seemed to admit being Party members. It still was not safe to be an “open” Communist, even in the “free loving” Sixties.

As the 1960s saw a resurgence of political activity, especially on the Civil Rights front, the CP began lending support to groups like CORE and NAACP, both of which had made their way to Seattle and Washington State to help solve the problems of segregation and racism.[iv] The PW publicized the movements that the CP supported, but these were one-way relationships. Groups like SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) saw the CP as the old guard—the “Old Left.” [v] Furthermore, many activist organizations—especially the anti-war movement—were under intense scrutiny by the FBI and did not want to be labeled “Communist” for fear of being discredited. However, many activist groups in the Sixties were more than willing to allow Communists to work with them as long as they stayed quiet about their Party affiliation.[vi] Regardless, there was a political price to be paid for associating with Communists, and a legal one, too, as many states and the federal government targeted Communists and Communist-linked organizations for surveillance and persecution.

In 1962, a faculty group at Central Washington University and a student group at UW, invited Party chair Gus Hall to the two campuses for a speaking engagement. These invitations directly challenged the State's prohibition against Communists speaking on college campuses and both administrations enforced the ban and Gus Hall was forced to speak off-campus. ( Peoples World February 10, 1962).A politically- and numerically-diminished organization, the Washington State Communist Party was not a popular group, and the paranoia surrounding the organization still persisted. In February of 1962 two professors from the University of Washington were fired for not signing a loyalty oath as required of all state employees. Designed to keep the Communists out of the University and other government jobs, the loyalty oath required signers to pledge that they were not Communists.[vii] The University did not stop there; Gus Hall – one of the Communist Party’s national leaders at the time – was not permitted to speak on the UW campus precisely because he was a Communist.[viii]

The state’s Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB) continued to hunt down old Communist fronts. Even the Washington Pension Union (WPU), which was practically moribund, remained under investigation. Under the McCarren Act, any organization that was essentially Communist had to register with the federal government as such, labeled a “communist front.” The WPU had actually been dissolved in 1961; thus, the SACB’s investigation serves to point to the state government’s paranoiac fear of Communism.[ix] In 1963 the Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., finally ruled that the WPU had in fact been dissolved and that its members could to longer be harassed.

Another witch hunt in 1963 led to Eugene Robel’s arrest and removal from his job at a shipyard in Seattle after he was accused of being a “communist” working near important defense projects.[x] In some ways, the Red Scare of the Fifties carried over to the Sixties, and continued to make life difficult for the Party. Even as late as June of 1964 the SACB was investigating yet another “communist front,” the Washington Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born. The WCFPFB had been active in defending Mr. Robel from losing his job at the shipyard, and had worked to keep many accused Communists from deportation. The WCFPFB’s executive secretary at the time was Marion Kinney, a leader of the Washington State Communist Party.

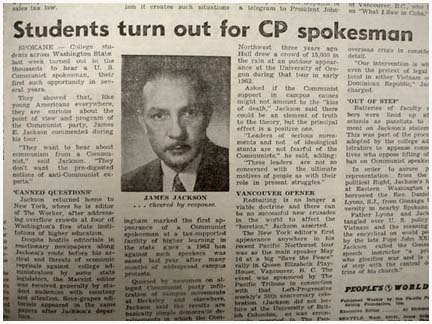

When the universities finally relaxed the ban on Communist speakers in 1965, James Jackson, editor of The Worker which was the Party's New York newspaper, spoke at WSU and UW. (Peoples World May 29, 1965)Nineteen sixty-four was a year of great change throughout the country and Washington State, as the Civil Rights movement—and other activist groups—turned up the heat on the status quo. As if to define the battles that would come, Governor George Wallace of Alabama came to the University of Washington campus to speak at the beginning of this pivotal year.[xi] Although considered by many to be a racist, Wallace as allowed to speak on campus, while the Communist Party was still denied appearance at the UW. In January, anticipating Wallace’s visit, to protest political discrimination, UW students in January 1964 demonstrated against President Odegaard’s ban of Communists from the campus.[xii] They pointed out that most colleges and universities, including nine in Oregon, no longer banned Communists from their campuses. Finally, near the end of the year, a Communist was allowed to speak on the campus; he was Henry Winston, an African-American party leader who had served time in federal prison for contempt under the Smith Act. [xiii]

A bold move for the WSCP occurred when Party member Milford A. Sutherland decided in 1964 to run for governor of Washington State. While not open about his Communist Party affiliation, Sutherland’s platform included the full range of Party positions, and The People’s World vigorously supported him. The newspaper touted his opposition to the loyalty oath and his challenge to repeal the McCarran Act. Sutherland called for the defeat of the “ultra-right,” for more jobs, for an end to the war in Vietnam, for free elections in the states of Mississippi and Washington, and, finally, for separation of the state from the military, monopolistic and economic domination of the Boeing Company.[xiv] Still, the fact that the WSCP and Sutherland did not come out and run his candidacy as a “Communist” ticket was significant. Members remained unsure about being open because of national and state laws that were still on the books.[xv]

All through the 1960s the CP concentrated energy and attention on Seattle's African American community. It supported civil rights initiatives early in the decade and later worked with the Black Panther Party. People's World October 7, 1967In 1965 Marines landed in Da Nang and the Vietnam War went into overdrive. Billions of dollars would be spent and a million lives would be lost in a fight to contain Communism. Back in Washington State, the CP and its members were already beginning to work within several movements that would come to define the activism of the Sixties. The war in Vietnam and Civil Rights, prime concerns of the WSCP, were specifically addressed at a meeting on October 30, 1965, when the Party simultaneously decided to pay “special attention to the Central District” of Seattle and concluded that the “peace movement must take on McCarranism … if [they] want to move forward.”[xvi]

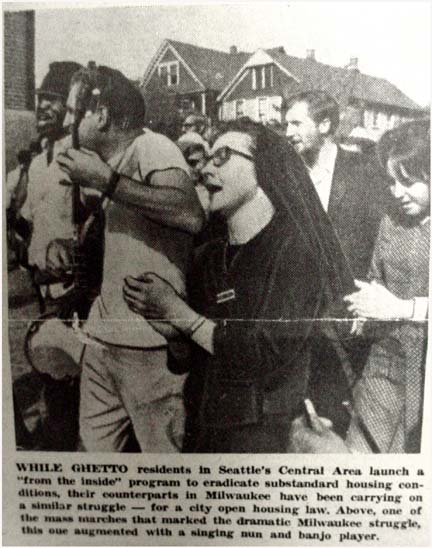

The WSCP Civil Rights focus was on the mostly-black neighborhood of the Central District, with a presence and commitment that dated back to the 1930s. In the 1960s some of the Party’s work stressed jobs for Blacks and revitalization of the Central neighborhood. [xvii] Lonnie Nelson moved with her family to the Central District so she could work on these issues within the neighborhood, itself (see Lonnie Nelson interview). In addition, the WSCP and its members supported and were active in the Central District school boycotts that were protests against the segregation in schools and the poorer quality of education for Blacks. Several members from the WSCP also traveled south in support of the Civil Rights movement.[xviii] The WSCP was very active in Civil Rights, especially because Seattle was far from an equitable place for minorities to live in the Sixties. Even though a good deal of effort was expended by some to discredit the Civil Rights movement as “communist,“ the movement, itself, embraced and accepted the Party’s members as supporters of its work for equality.

However, the WSCP still met resistance as a result of suspicions about its activities. Milford Sutherland responded in March of 1966 with regard to a Seattle Times article that accused the WSCP of “infiltration” of mass groups. Sutherland argued that the Times was only trying to smear the peace, Civil Rights, and Labor movements. [xix] This was often the response of most people opposed to mass movements, nervous about maintenance of the status quo. In fact, the U.S. Attorney General at this time, Nicholas Katzenbach, accused SDS of harboring Communists as members.[xx] It is no wonder, then, that so many organizations did not want to openly have Communists participating with them in their activities.

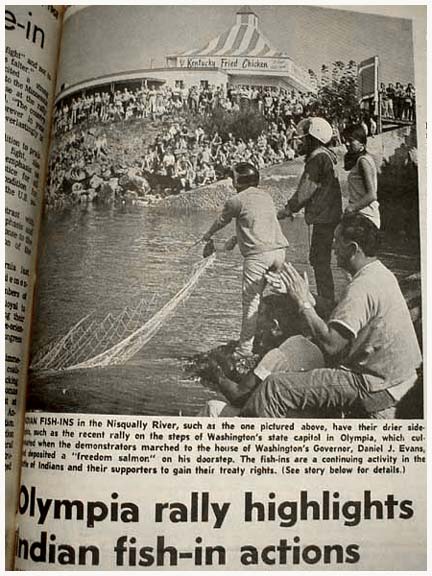

A People's World article celebrates 1968 "Fish-ins" to reclaim the treaty rights. (October 19, 1968).The WSCP began working with another civil rights movement when it expressed concern for Native Americans in Washington State. Party meeting notes taken in 1966 state that, with regard to Native Americans, “nearly all are being left behind in the march of the Johnson administration’s ‘Great Society’,” and show the WSCP vowing to “fight for the rights of the Indian people.”[xxi] In addition, the Peoples World reported in February of 1966 on the rights of Indians to treaties that had been broken by federal and state governments.[xxii] The WSCP took an active interest in rectifying what had been done to Indians in Washington State; specifically, Nisqually and Puyallup Indian fishing rights became a hard-fought battle that raged for quite some time. Members of the WSCP, like Lonnie Nelson, were directly involved in organizing protests and other efforts to get these tribes their fishing rights. The WSCP was one of the few groups aiding Native Americans at this time.[xxiii]

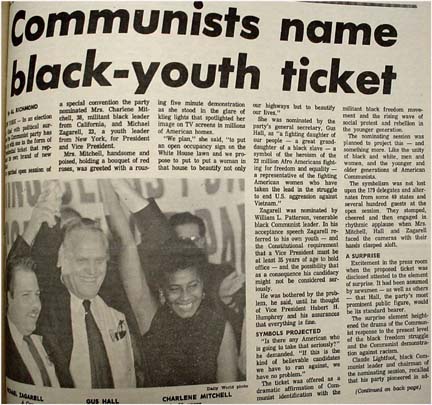

Nineteen sixty-eight saw an expansion of the CP politically at both national and state levels. Nationally, the CP—for the first time in twenty-eight years—decided to run candidates for President and Vice President of the United States. Charlene Mitchell, a Black woman, was nominated for President, but was entered on the “Free Ballot Party,” not the Communist Party.[xxiv] Politically, “communist” was still a dirty word; nonetheless, the Party seemed to be coming out of its shell. In Washington State, Milford Sutherland went on the offensive, again attacking the loyalty oaths still required for state office. More importantly, the ACLU decided to join the fight as well,[xxv] indicating that leftist organizations began to perceive that the CP was under attack over its First Amendment rights. This new political weight behind the CP’s defense was different from the early Sixties when leftist groups were unwilling to allow CP members to be open about their politics out of fear of legal reprisals for associating with known Communists.

More than any other development of the decade, the growing anti-war movement helped change the political climate. After nearly two decades of persecution and secrecy, the Communist Party was beginning to operate openly.The Black Panther Party was another group that the WSCP supported in the late Sixties. Nationally, the Black Panthers were harassed by police, which often led to violence against its members; in Seattle they suffered a similar fate. In December of 1968 the PW published an interview given to the paper by members of the Panther Party who voiced concerns about the treatment that they received from the police. The Panthers were often in close contact with the CP. After all, members of the WSCP were living in the Central District and helping the Black community directly. In fact, they had helped block Seattle police from raiding the Panthers’ office. To some Party members, the harassment of the Black Panthers had obvious similarities to the harassment that the CP had faced over the years.[xxvi]

Nineteen sixty-nine was the fiftieth anniversary of the CP in the United States. Nationally, congratulations came in from all over the world – the Soviet Union, Cuba and North Korea.[xxvii] In the same year, Angela Davis—later one of the Party’s most notable members—was fired from her job as a professor at UCLA for being a Communist. Davis, not at all shy about her membership in the Party, openly fought the school for reinstatement.[xxviii] Her actions demonstrated that the CP was willing to draw national attention by non-capitulation to opposition. As more groups came to the Party’s aid (like the ACLU), the CP finally found itself able to confront some of the governmental harassment issues that had plagued it since the Fifties. A lot of support was focused on the Party’s First Amendment rights, a universal concern for many organizations.

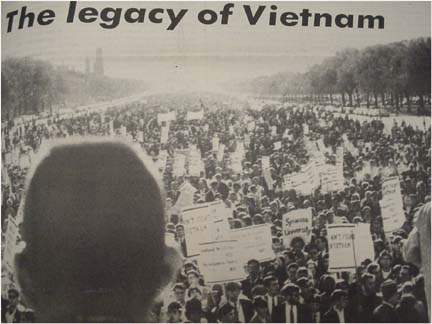

By 1969 the WSCP was putting even more effort into the anti-war movement. The CP had been speaking out against the war since the early Sixties, and Washington State Party members consistently participated in anti-war demonstrations. [xxix] However, the CP did have to face something of a split with the labor unions over their anti-war stance because most unions at this time were not against the war per se and very few ever really came out against the war.[xxx] It was a difficult decision because the CP had always been a worker’s party. In October of 1969 several members of the WSCP took a bus to San Francisco to participate in one of the largest anti-war demonstrations of the Sixties, a nation- wide moratorium on the war. The WSCP would remain active in the anti-war movement throughout the Seventies, all the way to the war’s end.[xxxi]

By the Sixties the CP had become a much-diminished organization. The Fifties and McCarthyism had taken their toll both on Party members’ morale and on membership levels, while international events had similar effects. Regardless, individual Party

The Party chose Charlotte Mitchell as its Presidential candidate in 1968. (People's World July 13, 1968)members pressed on at the national and the state level. In Washington State, the Party seemed to reenergize itself, especially by the end of the decade. In spite of their relatively small number, WSCP members enthusiastically participated in Civil Rights, the anti-war movement, the campaign for Indian rights, and even defended the Black Panthers. However, the Party still had its enemies—namely, the government, and, concurrently, the many people in the United States who felt that the war in Vietnam was all about arresting the spread of Communism. It is surely one of the ironiy positive things happened for the CP in the Sixties. The Party finally found its break with McCarthyism, and many of the laws that had discriminated against it were slowly removed from the books, or at least seriously stripped of power.[xxxii] At the beginning of the Sixties the CP was down but not out, and by the end of the decade the Party seemed to have found its legs again.

© Copyright Paul Landis 2002

Next: Closing the Century

[i]Lonnie Nelson Interview by Brian Grijalva, 26 February 2001, Special Collections, University of Washington, Seattle.

[ii]B.J. Mangaoang, Seattle CP member, wrote an article in the April, 1961, issue of the People’s World discussing this subject.

[iii]Marc Brodine Interview by Paul Landis, 25 February 2001. Video of the interview can be found in Special Collections at the University of Washington, Seattle.

[iv]“Fight against Seattle job bias inspired by Carolina example,” People’s World, 2 September 1961, 3.

[v]Walt Crowley, Rites of Passage: a Memoir of the Sixties in Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995), 21.

[vi]Marc Brodine Interview.

[vii]“’Loyalty’ issue simmers despite court turndown,” People’s World, 3 February 1962, 3.

[viii]”Gag on Gus Hall stirs up protest,” People’s World, 10 February 1962, 3.

[ix]“SACB sleuths shadow Pension Union’s ghost,” People’s World, 17 March 1962, 3.

[x]“Ruling due Nov. 25 in Eugene Robel case,” People’s World, 26 October 1963, 3.

[xi]“A cold shoulder for Gov. Wallace,” People’s World, 25 January 1964, 3.

[xii]“University sticks by its speaker ban; report assailed as cub on free speech,” People’s World, 18 January 1964, 3.

[xiii]“Campus issue sparks debate,” People’s World, 24 October 1964, 3.

[xiv]Marion Kinney Collection, Special Collections, University of Washington, Box 1.

[xv]Marc Brodine Interview. Brodine discusses how McCarthyism really arrested the party and in the Sixties still kept members from being too open about their politics.

[xvi]Marion Kinney Collection, Box 1. This contains minutes of various Party meetings from 1965 on.

[xvii]“New plan for Seattle ghetto,” People’s World, 7 October 1967, 3.

[xviii]Lonnie Nelson Interview.

[xix]“Press tries to make CP plan ‘secret’,” People’s World, 19 March 1966, 3.

[xx]James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets: from Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago

[xxi]Marion Kinney Collection, Box #1.

[xxii]“’Grass Roots’ forum to hear Indian fishing rights dispute,” People’s World, 5 February 1966, 3.

[xxiii]Lonnie Nelson Iinterview. The interview explores more of this topic. In fact, Nelson, herself, was quite active with helping AIM and various other Indian organizations, especially in Washington State.

[xxiv]“Communists name black-youth ticket,” People’s World, 13 July 1968, 1.

[xxv]“Drive captures interest,” People’s World, 19 October 1968, 3.

[xxvi]Lonnie Nelson Interview. She discusses this incident in more detail.

[xxvii]“U.S. Communist anniversary feted,” People’s World, 13 September 1969, 5.

[xxviii]“Black prof fired; storm brewing,” People’s World, 27 September 1969, 1.

[xxix]“Seattle students applaud Winston,” People’s World, 24 October 1964, 3. Henry Winston, a CP national leader, came to the UW and one of the things that he spoke out against was the war in Vietnam.

[xxx]Marc Brodine Interview.

[xxxi] Loc. cit.

[xxxii] Loc. cit.