Edward W. Graham worked at Skinner & Eddy Shipyards, where he was a card-carrying member of Boilermakers Local #104 and Shipbuilders Industrial Union Local #325 of the Industrial Workers of the World.[1] Outside of the shipyard he was an active member of both unions. He was a delegate for Local #104 at the 1920 Washington State Federation of Labor Convention in Spokane.[2] At meetings of SBIU #325 he acted as recording secretary.[3] He audited the books and served as chairman for the IWW’s Northwest District Defense Committee, which was charged with providing for the legal defense of members in jail or on trial.[4] Graham was also known by the aliases Agent #17 and E.W.G. He was one of several paid spies for Associated Industries of Seattle, an organization of local businessmen that sought to cripple organized labor in the city and Washington State. Their work helped Associated Industries in its campaign against Seattle’s left-leaning AFL locals and the IWW by gathering information on the leaders, membership, and politics of both organizations, and casting them as violent revolutionaries who posed an imminent threat to public safety.

The anti-labor espionage that took place in Seattle in the years after World War One was set against a backdrop of genuine labor radicalism and popular hysteria over the threat of “Bolshevism.” In the United States, radical movements and organizations had gained momentum since the latter half of the 19th century, the most notable being the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World. In the Pacific Northwest, the IWW had been especially strong, as was the SPA, and even Seattle’s American Federation of Labor movement leaned further to the Left than the national body. Labor radicalism in the Pacific Northwest would reach its high water mark with the Seattle General Strike in February 1919.

The rise of the Left in this period did not come without resistance. Anarchists, socialists, and Wobblies found themselves subject to violence, arrest, and imprisonment by government authorities. Local police and federal agents were also assisted by private citizens, who styled themselves patriots defending the United States from foreign radicals, but also acted out of self-interest. Associated Industries was one such group of private citizens. Rather than confront their opponents directly, Associated Industries employed spies to infiltrate Seattle’s AFL and IWW locals. These spies kept tabs on labor activities and provided information that was often exaggerated or falsified and used deliberately by Associated Industries as part of a propaganda campaign through local newspapers to turn public opinion against labor.

War’s Effect on Labor in Seattle

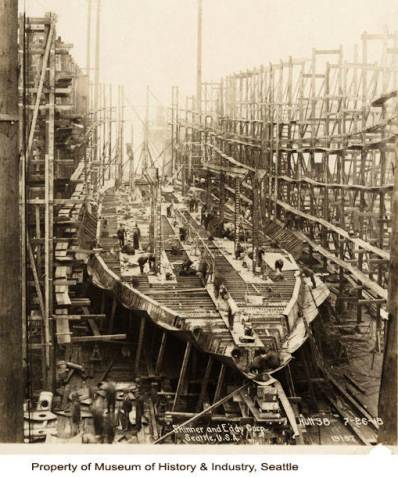

During World War One, Seattle experienced a labor boom which drastically altered labor relations in the city. Much of this growth was experienced in the shipyards, where an increased demand for ships meant a greater demand for workers. Unions in the shipyards grew in size and clout, and the shipyards themselves featured a highly politicized workplace culture.[5] The growth of the shipbuilding industry also meant growth in the building trades and service industries, leading to a general hiring boom that saw tens of thousands of workers enter the city.[6] Turnover was high as an abundance of jobs allowed many workers to move from job to job seeking higher wages, and constant demand for workers led to a rising wage scale.[7]

The massive influx of new workers, many of them holding radical political views, meant growing pains for the city’s AFL movement. According to William Short, President of the Washington State Federation of Labor, Seattle’s AFL unions faced three main obstacles during the First World War. First, membership increased by 300%, making it hard to assimilate new members into the AFL’s culture. Second, many of its older members were drafted by the government for the war effort, robbing the movement of their influence and experience. Finally, the Pacific Northwest, with Seattle at its center, became the site of the IWW’s most effective propaganda and organizing efforts to date, and its influence on these newer, “inexperienced” workers was evident.[8]

The growth in labor membership and the radical turn of its politics created conflict within the Seattle AFL. Radicals achieved a great degree of influence within its main organizational body, the Central Labor Council, but were opposed by more conservative leaders at the local, state, and national level. Embarrassed by the 1919 General Strike, the AFL called on its international unions to rein in the Seattle locals, and some officers from the internationals arrived to personally investigate and purge their leadership.[9]

The same factors that generated conflict within the local AFL movement also brought the AFL into conflict with the IWW. The IWW’s presence in the Pacific Northwest had been greater in rural areas prior to the war, until the hiring boom caused many of its members to migrate to Seattle, where they merged themselves with the AFL locals.[10] Generally, the AFL was conservative, sought to distance itself from political controversy, and primarily focused on advancing the interests of the craft unionists who constituted its membership. It was also exclusionary to women, non-whites, immigrants, and unskilled laborers, and favored negotiation over direct action in disputes with employers. In contrast, the IWW believed in control of the workplace by workers and advocated “One Big Union”, under which the working class would be united, regardless of skill, race, or national origin. The IWW was well known for its use of direct action as a means of advancing the interests of the working class. Their refusal to compromise frequently brought them into conflict with others in the labor movement, including radicals who were otherwise sympathetic to their politics.

The Bosses Organize

On March 12, 1919, a month after the conclusion of the General Strike, Seattle’s largest employers founded Associated Industries of Seattle, merging several earlier employers’ associations, including the Waterfront Employers Association, Metal Trades Association, and the Master Builders Association.[11] Its first president was Frank Waterhouse, head of the WEA, owner of the shipping firm Frank Waterhouse & Co., and reputedly a millionaire with numerous investments in local banking, metalworking, and retail companies.[12] Associated Industries held the same anti-labor stance as its predecessors, but was better organized and more sophisticated, borrowing its tactics from those used against pacifists and radicals during the war.[13] Associated Industries also took a page out of labor’s playbook, and appealed to the class consciousness of employers by presenting itself as a defense against working class tyranny.

The position of Associated Industries was not new. The open shop ideal of total employer control over labor relations had been around since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Despite showing greater concern for industrial relations than their predecessors, employers’ attitudes had not changed. Earlier in the century the National Association of Manufacturers cast organized labor as a threat to the stability of the United States and the liberty of its citizens.[14] The NAM understood the importance of the press in promoting its agenda and attempted to influence public opinion through paid articles in national news services, as well as its own journal, American Industries, which was distributed to Congressmen, newspapers, and workers alike.[15]

The agenda of Associated Industries extended beyond the removal of radicalism from the labor movement and sought to make Seattle a right-to-work city. Its leaders advocated what they termed the “American Plan,” which would have prohibited closed shops and made union membership optional under an open shop system.[16] Associated Industries claimed the American Plan offered “justice for the employee, fair play for the employer,” and would lift Seattle out of the “chaos” and “class dictatorship” imposed by the Central Labor Council.[17] What Associated Industries wanted, essentially, was a labor movement that did not strike and stayed out of politics. As part of its open shop policy, it financed its own company union, the Associated Craftsmen and Workmen, which supplied workers to keep its members operating during strikes. Most of the ACW’s members were former servicemen and it was staunchly nativist, prohibiting immigrants from membership.[18]

This open shop campaign was not an isolated occurrence, but part of a national trend involving numerous employers’ associations. Associated Industries of Seattle was the first of these post-war open shop movements, which started independently of one another in response to a labor movement which had grown stronger during the war and refused to surrender what it had gained.[19]

Propaganda distributed by Associated Industries took a reasonable tone necessary for swaying public opinion, but in private communication with labor it was hostile. In a letter to William Short, Frank Waterhouse rebuffed Short’s attempts to negotiate a settlement, replying that such efforts “would serve no useful purpose in our judgment, but would tend only to useless debate.”[20] That Associated Industries employed spies to infiltrate and discredit their opponents shows its hostility to organized labor went beyond mere rhetoric.

.jpg)

The Sources: Broussais Beck and Roy Kinnear

Evidence of the existence and activities of Associated Industries’ labor spies comes from the personal papers of Broussais C. Beck and Roy J. Kinnear, two Seattle businessmen who played an active role in the organization. Beck was manager of the Bon Marche, which was the focus of a boycott organized by the Central Labor Council.[21] Beck likely came to Associated Industries through his business relationship with Frank Waterhouse, who had an interest in the department store.[22] He was alleged by The Union Record to have a supervisory role in Associated Industries’ propaganda efforts, and this is supported by the presence of hundreds of reports from two agents, Edward Graham and Agent #106, in his collection of personal papers.[23] He reported to Alfred Bickford, the organization’s executive secretary, who in turn passed this information on to Waterhouse and the board of trustees.[24] Roy Kinnear was a Seattle businessman engaged primarily in real estate who sat on the board of trustees for the Building Owners and Managers Association of Seattle, an affiliate of Associated Industries.[25] By 1920 he was 1st Vice President of Associated Industries, President for 1923-24, and would later serve in the Washington State House of Representatives from 1937-46. [26] Kinnear’s spy reports are sparse in comparison to those found in Beck’s personal papers, and it is uncertain how long those spies were employed or how effective they were. It is also unknown what role Kinnear played in Associated Industries’ espionage campaign, if spies reported directly to him, or if these reports ended up in his personal papers by accident or because of personal interest.

The Spies

-cr.jpg)

Associated Industries’ spies vary in terms of the scope and nature of their activities, number of extant records, quality, and degree of professionalism. Edward Graham and Agent #106 submitted reports on a daily or near-daily basis for about a year, and gained the confidence of many trusted people affiliated with both the IWW and the Central Labor Council. The records of Agents #172, #181, #317, and Operator C are sparse and of varying quality. The lack of records indicates their employment was either brief, or that most of their records were either destroyed or lost.

There is no record as to whether these spies were employees of a private detective agency or hired directly by Associated Industries. Anti-union activities were a staple of private detective work, and large firms such as the Pinkerton National Detective Agency and Williams J. Burns International Detective Agency had offices in most American cities, including Seattle.[27] The agent numbering system of Pinkerton spies and those employed by Associated Industries are the same, although it may be that the system was an industry standard introduced by the Pinkertons and used by former employees or adopted by other agencies.[28] It is difficult to tell who employed these agencies because the poor reputation of labor espionage meant most records were kept hidden or destroyed.

All reports are neatly typed with few errors, suggesting they were dictated to a stenographer or reproduced from handwritten reports by a typist. Differences in formatting indicate reports were not typed on the same machine, and there appear to have been multiple typists and stenographers at work. Typing was not as widespread a skill in the early 20th century as it is today, and stenography remains a specialized skill requiring years of training. Those most likely to possess such skills would have been office workers, not industrial workers or craftsmen.

There are three reasons it is likely these spies were employed by and answered directly to Associated Industries. First, detective agencies commonly fed their clients false information or deliberately instigated labor unrest to ensure their continued employment.[29] By 1914, employers were increasingly organizing their own intelligence services to avoid the added costs that came with hiring a detective agency.[30] Second, one of the hallmarks of labor spies employed by private detective agencies was the assumption of key leadership positions in labor unions so as to cripple them through deliberate mismanagement and the creation or exploitation of internal strife.[31] Associated Industries’ spy reports are notable for the complete absence of this kind of activity, which would have been detailed, had it taken place. Finally, Broussais Beck already had professional experience as a spymaster in his capacity as manager of the Bon Marche. Department stores were an early site of labor surveillance because they are easy places to observe employees.[32] Although initially employed to ensure honesty and quality of service, it was not long before spies began discouraging worker organization.[33] This is confirmed in a report by Agent #106 concerning a conversation he had with a store clerk. One morning he visited a small men’s clothing store under the pretense of making a purchase and asked a clerk if the store was organized. The clerk replied that his store and many others like it were organized, but stores like the Bon Marche were not because of the efficiency of store detectives in spotting union activists.[34]

Edward W. Graham (Agent #17 or E.W.G.)

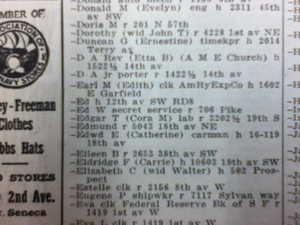

What is known about Edward William Graham comes from the U.S. Census, city directories, birth and selective service records and an identified grave marker. Graham was born in either Reedsburg or Portage, Wisconsin in 1890.[35] He was employed at Skinner & Eddy Shipyards in 1917 as a helper at the start of the wartime boom.[36] By 1919 he had been promoted to foreman.[37] The 1920 census described him as 29 years old and living with his wife, Winifred, in a working class residential hotel at 706 Pike Street.[38] A city directory for the same year lists his occupation as “secret service,” a synonym for private detective.[39] He held several different jobs during the 1920s, working as a clerk, civil engineer, and salesman.[40] By 1930, at the age of 40, he was working as a manager for a coal company, and his financial circumstances had improved; he was a father of three, owned a house valued at $8,000, and employed a domestic servant who lived in the home.[41] He was also manager and president of the Industrial Service Association, a business association active from 1929 to 1936.[42] In 1940, he was 50 years old, divorced, and renting an apartment for $25 a month.[43] Census data also shows that he was unemployed, but still receiving income, and that he had a 9th grade education.[44] Winifred had custody of the children and was employed as a domestic servant, while his eldest son, Edward, had dropped out of school and taken a full-time job to help support the family.[45] Edward W. Graham died in 1956.[46]

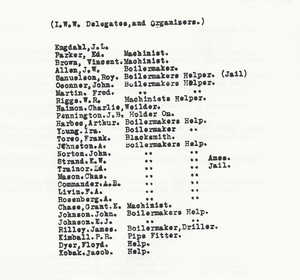

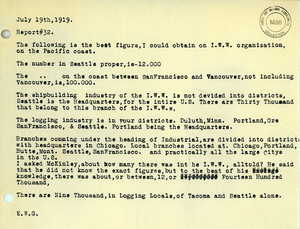

From approximately May 1919 to June 1920, Graham was employed by Associated Industries as a spy within the IWW and the shipbuilding industry. His first recorded assignment took place outside of Seattle, when he spent a month traveling among logging camps in Thurston and Mason Counties.[47] At this time he would have been on leave or temporarily laid off from his job at Skinner & Eddy as wartime production was scaled back. He described conditions in these camps as grim, with IWW loggers at war with the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (4Ls), a patriotic company union formed to check the IWW’s influence in the industry.[48] His work with the Wobblies may explain why upon his return to Skinner & Eddy he was a member of both the IWW’s Shipbuilding Industrial Union Local #325 and the AFL-affiliated Boilermakers Local #104.[49] Furthermore, he held positions of responsibility. He frequently acted as recording secretary at SBIU meetings. On September 28, 1919, he was elected chairman of the Northwest District Defense Committee, which oversaw the defense and release of imprisoned IWW members.[50] Less than two months after his election, he would assist police in a raid on IWW headquarters that resulted in the arrest of one of its leading organizers, and the seizure of membership lists naming every member in the Seattle area.[51] Graham also claimed to have assisted the Department of Justice in locating and arresting a group of Russian radicals allegedly involved in a plot to blow up Duthie Shipyards and murder the wife of owner J.F. Duthie.[52] There are several other references to police raids in his reports, suggesting he and other agents were working with law enforcement.[53] A month after the aforementioned raid on IWW leaders, he was still auditing the books of the IWW’s General Organization and Northwest District Defense Committees, and passing financial and organizational information to Broussais Beck.[54]

Graham’s activities with the Boilermakers figure less prominently than those with the SBIU and IWW, but he was entrusted with responsibility with them as well. Graham’s final report covered the 1920 Washington State Federation of Labor Convention in Spokane, which he attended as one of 57 delegates for Local #104.[55] His chief focus was its IWW presence. Graham estimated approximately 320 out of the 800 delegates present were Wobblies.[56] Graham’s membership in Local #104 was necessary to obtain work at his trade in the shipyards so that he could operate among SBIU #325 and the IWW.

Clues to Graham’s identity come from three reports under the initials “E.W.G.” E.W.G. and Agent #17 were previously thought to be separate individuals, however the minutes of a meeting of the IWW’s Northwest District Defense Committee record an E.W. Graham elected as chairman, and this was the same meeting at which Agent #17 was also elected chairman.[57]

Edward Graham’s dual roles as shipyard foreman and union officer are interesting because they are unusual. If a union local was strong enough, it could force employers to use union members as foremen. However, because their status as low-level managers made them susceptible to influence from employers, they were untrustworthy as leaders. Oddly, this suspicion did not fall on Graham. It is unknown how or when he was turned by management, but he was apparently persuasive enough with both the Boilermakers and SBIU to be elected to positions of responsibility. This lapse of judgment turned out to be a grave mistake.

Graham’s work placed him in contact with management at other shipyards, and because the shipyards were known hotbeds of labor militancy with a fluid workforce, employers would naturally be in communication with each other or their agents on organizing activity. [58] He was probably part of a larger network of spies whose existence is hinted at by the agent numbering system. This system could have been instituted by Associated Industries’ handlers, but because a shipyard spy network was probably already in existence, it would have been incorporated into its espionage campaign, with the original numbers being kept when possible to simplify record-keeping.

His activities probably precluded future work in either the shipyards or as a labor spy by 1920. The listing of “secret service” in the city directory suggests he no longer had any need to keep that occupation hidden. He may have had the foresight to see work in the shipyards as an unreliable source of income after the government contracts that fueled the wartime boom dried up. His service was probably rewarded given the apparent ease with which he transitioned into white collar work and management.

Other Spies of Associated Industries

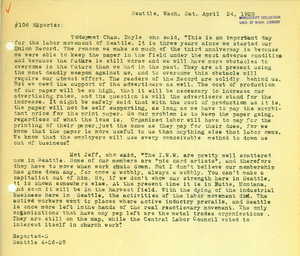

Agent #106 is an enigma despite the large number of reports he left behind. His reports say very little about their author, and his age, national origin, politics, or motives could not be discerned. His style was objective, focusing strictly on what he observed without hint of bias. What is known comes from the reports themselves. Agent #106 was employed by Associated Industries from approximately April 1919 to April 30, 1920. He did most of his work at the old Labor Temple at 6th Avenue and University Street, catching up with his sources and attending meetings of the Central Labor Council, Metal Trades Council, and Boilermakers Local #104, of which he was a member. He attended meetings well into the night, often leaving after midnight. It does not appear that he worked at his trade very often. He was present during the morning and afternoon often enough to suggest he was not regularly employed. If he was at work in the shipyards, he did no reporting on activities there, as Edward Graham occasionally did. Although there is no proof he held a paid position in the union, it would explain both his frequent presence at the Labor Temple and his many acquaintances, as well as his access to copies of the local’s financial statements.[59] His reports suggest he was a loquacious individual who gathered information by befriending his sources, and keeping his eyes and ears open for important information. The following excerpts from his final report indicate his apparent skill at winning friends:

Short, Buck, and Doyle were labor moderates who adhered to the program of the AFL’s national leadership. Coats’ Triple Alliance was a coalition formed by the Washington State Federation of Labor, Railroad Brotherhoods, and the Washington State Grange, with the aim of forming a politically moderate labor party at the state level.[61] Other notables Agent #106 named include radicals such as Frank Turco of the Blacksmith’s union, Percy May of the Longshoremen, Phil Pearl of the Barbers, and socialist speaker Kate Sadler, as well as progressives like Jimmy Duncan and J.C. Mundy of the Central Labor Council.[62]

Agent #172 was most likely a union member earning money on the side as an informant. At one point he asked his handler for a raise, claiming if he were paid more he would have more time to get better information.[63] His three reports, dating from March 8 to April 2, 1920, concern the activities of two Carpenters locals, #131 and #1335. The first two reports concern meetings of these locals, and the third covers a Carpenters District Council meeting, where he was present as a delegate for Local #1335. Local #1335 was in the midst of a purge conducted by an officer from the international, who had expelled radicals from its leadership and replaced them with his own chosen officers.[64] Agent #172 reported that both locals were in bad shape, estimating it would take five or six months for them to collapse if Associated Industries kept up its campaign against the Central Labor Council.[65] In his report on the Carpenters District Council meeting, Agent #172 further confirmed that Associated Industries’ propaganda campaign was making it hard for the union locals to weather the open shop campaign.[66] The District Council had made a conscious effort to distance itself from labor radicalism, and denied one of its affiliated locals, the radical Shipwright and Joiners #1184, the right to vote at meetings, which prompted threats from the local’s delegates that it would leave.[67]

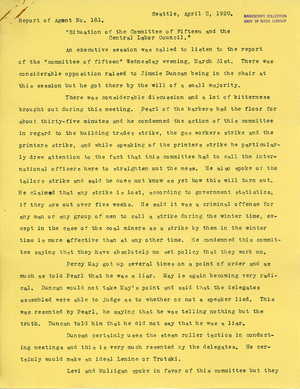

Agent #181 was a politically conservative member of Electrical Workers Local #944. Attached to the main body of his report on the March 9, 1920 meeting of the Central Labor Council is a brief report on a meeting of Local #944, and in the main body he refers with familiarity to Electrical Workers #77 as “Local No. 77.”[68] His use of “we” in reference to the Central Labor Council and “Brother” when referring to its vice president is further confirmation of his labor affiliation.[69] He claimed that his knowledge of the “inner workings in several countries” made him uniquely qualified to understand the threat posed by the Central Labor Council.[70] His credibility as an authority on the subject is doubtful because his claims consist of gross inaccuracies coupled with a hatred of all things “Bolshevist.”[71] He was most likely a liar or crackpot whose knowledge of revolutionary movements came from rumors and sensational stories found in popular newspapers like The Seattle Daily Times, Post-Intelligencer, and Star. If his claims of knowledge were true, he would probably have been of English origin. His English reads as if he were a native speaker, and his vocabulary and diction suggest he had some education. His record consists of two reports concerning the Central Labor Council, made on March 10 and April 2, 1920. The first report was observational, noting a recommendation by the board of the Central Labor Council that efforts against Associated Industries be focused on the Bon Marche.[72] His second report was of an inflammatory nature and featured contradictory statements regarding the Central Labor Council’s strength. He claimed it was plagued by financial trouble and infighting, but also described it as a powerful revolutionary organization poised the take over the city and institute a workers’ soviet.[73] He described Council meetings as dominated by radicals, which he attributed to the presence of Council President Jimmy Duncan, who was described as having the makings of “an ideal Lenine or Trotski [sic].”[74] Contrary to Agent #181’s claim, Duncan was a progressive who was firmly within the AFL camp, and worked to rein in radicals like Pearl, May, and Turco. Seattle’s AFL radicals may have been influential, but they were not Marxists. Their sympathies with the Russian Revolution were based on class consciousness, not ideology.

Agent #317’s reports date from March 11 to April 1, 1920, and consist of one report on the Central Labor Council and two concerning the Private Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Legion, an obscure veterans’ organization. Almost nothing is known about his identity, but his membership implies he was a veteran. Like Agents #106 and #172, #317 was an observer and reported the Central Labor Council would be focusing its efforts at the Bon Marche, and would be attempting to coordinate its campaign with labor organizations across Washington State.[75] The reports on the Private Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Legion are interesting for the opinions of his source, Frank Pease. Pease was a paid organizer for the organization, and a bitter ex-serviceman who harbored a grudge toward Jews, civilians, and officers of the International Longshoreman’s Association, promising violent retribution to all three.[76] Agent #317 agreed with Pease, so far as respect veterans were concerned, commenting that Pease’s views “show he is a genius or no fool.”[77]

Operator C left one report, dated March 19, 1920, summarizing the labor situation in Seattle. The exact nature of his role is unknown. The title of “Operator” is unique among these reports, but it seems he was not the only one. The content is comprehensive, indicating it was probably gleaned from a long-term investigation or sourced from the reports of other spies. Operator C considered Associated Industries to have the upper hand at the moment, but warned that it should remain on guard. He recommended a peaceful and favorable settlement on the waterfront as crucial to future plans because of the organization and militancy of the ILA and Boilermakers. He advised keeping the electrical workers isolated within their locals and considered the carpenters, tailors, and printers nearly finished. No mention was made of the IWW, suggesting they were no longer a factor. Although labor had suffered some setbacks, he warned that the Union Record remained their most powerful tool because of its influence over workers and small business owners. To counter the Record, he advised building up the Labor Industrial Journal to appeal to smaller businesses and moderate union members.[78]

Finally, there is a single report from an individual named “Wahke,” that is notable for its author’s name and the format in which it appears. “Wahke” appears to be a surname. A search for this surname in census records indicates it is of either Native American or Austrian origin.[79] It is the only extant report that is not typed, and it was addressed directly to Broussais Beck. There is no date given, and its contents are brief, inquiring about a man named “Johnson” who was a conservative leader in the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Council.[80]

Propaganda in Industrial Espionage

The quality of the information provided by Associated Industries’ spies varied, as did its application. They range from diligent collectors of information with remarkable skills of memory and persuasion such as Agent #106 and Edward Graham, to men of highly suspect character like Agent #181. Most reports were used for the traditional purposes of gauging union strength, identifying organizers in the workplace, and keeping abreast of union activities, but some were used in an early and creative application of a new idea that emerged after World War One. During the war, the federal government carefully applied words and images to manipulate the opinions and emotions of citizens, and their effectiveness was not missed by employers.[81] While some employers applied these methods to cultivate a docile work force, Associated Industries used the information gathered by their spies to spread misinformation about their opponents and create the illusion of a looming threat posed by the labor movement. Evidently this strategy was successful. By 1920 a substantial number of businesses in Seattle had become members.[82]

In light of efforts to discredit the IWW and Central Labor Council, it makes sense that they would collect gross exaggerations from unreliable spies like Agent #181 as evidence of a threat to public safety and private property. Agent #181’s hysteria mirrored propaganda disseminated by Associated Industries to newspapers and the general public, though in a less refined form, because it conflated progressive labor politics with Marxism and syndicalism.[83] Jimmy Duncan was a confirmed progressive committed to working within the AFL, who opposed both the IWW and the One Big Union, not a successor to Lenin or Trotsky. As Seattle’s representative to the AFL’s national convention in 1919, he cast the only vote against the reelection of President Samuel Gompers, and repeated this action the following year.[84] Seattle’s AFL movement had a strong regional identity, with loyalties centered on trade councils and the Central Labor Council, and even its moderate members were militant in comparison to the national body.[85] Progressives like Duncan held the Seattle AFL together; they were militant like the radicals, but pragmatic and able to work with more conservative members as well.[86] Agent #181’s warning of imminent revolution in 1920 also contradicted the sober assessment of Agent #106 that radicalism was losing support.[87] Although he lacked the deliberation found in Graham’s reports, this was a case in which a disreputable labor spy would have been an asset for an employer, rather than a liability.

Unlike Agent #181, Edward Graham’s work stands out for its deliberate use of misinformation. A financial statement for the IWW’s Bail and Bond Committee claimed $11,664 on hand after bail payments.[88] This is too large a figure for an organization whose members were frequently in jail or on trial, especially at the local level. There is no indication this figure was ever published. It could have been challenged and raised questions in the public as to its veracity. Instead it would have been alluded to by Bickford or Beck toward prospective allies or members of the press as a measure of the IWW’s financial resources. This would not have been difficult because such men were respectable members of society, as opposed to the IWW, who were characterized as low class, unruly, and foreign. In the face of such heightened patriotism, the IWW was too unpopular to win over the public.

Graham provided exaggerated estimates of meeting attendance and membership that gave a distorted picture of the looming threat posed by the IWW: "The average employer is paying no attention to the strength this organization is gaining. In the past six months, [Shipbuilders Industrial Union Local] #325 has increased its membership by four thousand eight hundred. The total membership is about nine thousand."[89]

This same report also alleged "The hall is the basement of the Postal Building, and at all times during the day or evening, there are from three to five hundred in this hall." As with the financial statement, the numbers given are too high to be taken credibly. It conveys both the impression the IWW was growing unchecked and that hundreds of dangerous Wobblies could be found in Seattle’s basements. The public was already familiar with this image in the form of the deranged, bomb-throwing foreign anarchist who appeared regularly in newspaper illustrations. It did not matter that such images had little to do with reality or that no one encountered such figures in their life because these images were accepted as real.

A similar impression is found in Graham’s reports on the IWW’s presence in the state of Washington. His description of the war between the IWW and the 4Ls paints an image of a dark forest teeming with foreign revolutionaries beyond the edge of civilization. Given the anti-immigrant sentiment prevalent in the Red Scare, it made sense to highlight the presence of Serbian Wobblies to give the IWW threat added gravity. The 4Ls were probably not as beleaguered as Graham makes them out to be. By 1919, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen had made significant headway in challenging the IWW as the dominant labor organization in the forests, and had won over many workers to their side.[90] This was not generally understood by the public and the general impression was that the IWW remained a threat in the hinterland. Graham’s report from the 1920 Washington State Federation of Labor Convention conveyed the impression that IWW influence remained alarmingly high. Once again, his estimate of 40% should be taken with a grain of salt in light of the suppression experienced by the IWW.

Although these examples refer to the IWW, their impact was not exclusive to that movement, and had an effect on the AFL as well. Because the Wobblies tended to also be AFL members, it was very difficult for non-IWW affiliated unionists to dissociate themselves. There was also little understanding among the public of the varieties of political thought at work. It did not matter that the IWW and AFL were in conflict with one another, or that a variety of political positions were represented in both movements. What was portrayed was a blanket radicalism that appeared to have spread like a cancer through all segments of the labor movement and threatened public safety. Although radicals were undoubtedly influential in Seattle’s labor movement, they are overrepresented in agents’ reports. Because they were the focus of observation, their repeated presence actually served to heighten their profile.

It is difficult to measure the full impact propaganda had on labor, given the intense legal pressure it already faced in the form of criminal syndicalism laws. Such laws were rigorously enforced in Washington, and were intended to weaken radical movements by making it a crime to promote force or sabotage as a means of political or social change in speech or print, or belong to an organization that advocated such activities.[91] However, under such conditions, it would have framed Associated Industries’ goals as in accordance with those of the government, and those of its opponents as in defiance.

Propaganda and the Press

Central to Associated Industries’ campaign were efforts to sway public opinion through local newspapers. Articles were published which presented a clear bias in favor of Associated Industries and the American Plan, treating labor unions as either anti-American or the unwitting tools of foreign agents. Advertisements were featured that presented its agenda as sensible and pro-American, while condemning the Central Labor Council as misguided or un-American. Associated Industries also published its own newspaper, The Square Deal, as well as bulletins circulated among employers, workers, and members of the press. The National Association of Manufacturers used the same strategy during its open shop campaign over a decade before. Like Associated Industries, the NAM consisted mostly of mid-level and locally prominent business owners who lacked the resources of giants like U.S. Steel, but had a wealth of political and social connections.[92] Invisible to the public, these networks of personal and professional relations allowed them to appeal as fellow citizens whose motivations reached beyond their own personal interest and extended to the safety and prosperity of their city and country.

Management at the Seattle Daily Times and Post-Intelligencer regularly ran headlines, editorials, and articles sensationalizing allegations of violence and revolutionary plots to overthrow the government. One issue of the Times featured a full-page editorial by former mayor Ole Hanson, which conflated anarchists with Bolshevism and the IWW.[93] Hanson’s lack of accurate or honest analysis did not matter to a reading audience ignorant of distinctions between these groups and their respective ideologies in the first place. When a member of the ACW was beaten by longshoremen for helping load rifles and ammunition destined for anti-Bolshevik forces in Siberia, the Post-Intelligencer highlighted his military service record, and claimed the attack was proof of ILA anti-Americanism.[94]

Staff writers at both the Times and Post-Intelligencer wrote articles which echoed the views of Associated Industries. Several months after its foundation, Associated Industries was featured favorably in the Post-Intelligencer, complete with a copy of the declaration of principles circulated in its own publications. One Times article lauded both its vocational education programs for youths and its efforts to create a partnership between labor and capital.[95] Another was published after a week of advertisements for a meeting organized by Associated Industries, which featured Stephen C. Mason and J.P. Bird of the NAM as speakers. Mason and Bird spoke of the necessity for organization among employers, called for tougher immigration laws to weed out radicals, and demanded that unions be held responsible for the financial losses incurred by strikes.[96]

The Seattle Star’s stance on labor was less hostile, but as uncompromising as the Times and Post-Intelligencer on the issue of “Americanism.” Despite the general anti-labor hysteria of the aftermath of the Centralia Massacre, the Star did publish articles favorable to the AFL. On the same day news of the violence broke, the paper praised the United Mine Workers for working toward an agreement with employers to end a nationwide strike.[97] Shortly after Centralia, William Short was lauded for reining in the Seattle AFL and removing radicals from its leadership.[98] However, for much of 1919 and 1920 its front pages carried the slogan, “On the Issue of Americanism There Can Be No Compromise,” and its articles were highly critical of radicalism and labor militancy.

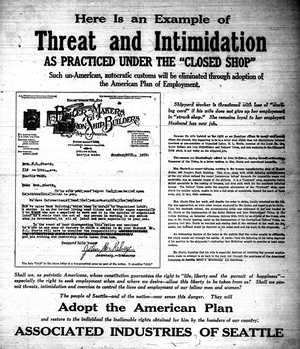

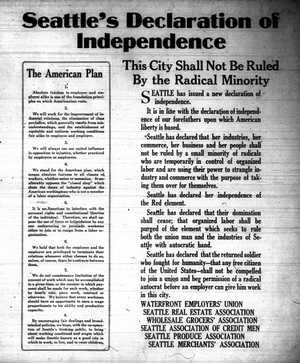

Associated Industries played on patriotic sentiment in the weeks leading up to the anniversary of the armistice with a series of advertisements presenting its goals and blasting the Central Labor Council for endangering public safety and liberty. Between October 29 and November 9, ads sponsored by Associated Industries, its affiliates, and allied commercial organizations ran in the Seattle Times, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and the Seattle Star. On October 30, the Star and Post-Intelligencer ran an ad detailing the principles of the “American Plan.”[99] Another ad, intended to appeal to workers, urged employer not to cut wages in the face of the coming winter.[100] Advertisements could also be scathing, as seen in a full-page ad which featured a reproduced letter from the business agent of Boilermakers Local #104 informing the wife of a member that her husband would be barred from working if she continued to work at a business whose workers were on strike.[101] The ad promised, “such un-American autocratic customs will be eliminated through adoption of the American Plan of Employment.” An ad in the Post-Intelligencer, three days before Armistice Day, appealed to patriotic nostalgia with a proclamation of Seattle’s “independence” from the tyranny of a “radical minority.”[102] Affiliates sponsoring ads included the Master Builders Association, Master Printers’ Association, Dyers and Cleaners Club, and the United Metal Trades Association. Advertisements also appeared from closely related groups such as the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and Kiwanis Club.

Associated Industries publications such as The Square Deal were used to reach readers from all walks of life. Members distributed copies in their places of business for employees to read and issues were sent to most of Seattle’s newspapers. The Square Deal featured articles and speeches sharing its views, as well as business and labor news, and cartoons which routinely cast the IWW, the Left, and organized labor in an unfavorable light. Most of its content was sourced from other publications.[103]

The propaganda campaign of Associated Industries took public fears of anarchism and Bolshevism and combined them with the increased patriotic fervor of the coming Armistice Day celebrations to cast their opponents as unpatriotic and dangerous to American values. Newspapers were filled with reports of government raids against foreign radicals and articles that praised the courage of returning servicemen. Many were angered by the United Mine Workers’ strategic decision to strike prior to the onset of winter, threatening the nation’s coal supply, and this was described as another example of unions holding the public hostage for its own narrow agenda.[104] Parallels to the Central Labor Council and the Seattle General Strike were easy to make.

The Centralia Massacre of November 11, 1919 was the tipping point that turned public opinion against labor. The following day, the Times was awash in patriotic fury, with photographs of American Legion members killed or wounded by the Wobblies dominating the front page. The same issue featured an editorial condemning the “slaughter of discharged servicemen by I.W.W. assassins” and asserted “the American Bolsheviki here [Centralia] acted precisely as the planners of the Seattle general strike.”[105] The editor then issued this warning:

“Organized labor must be made to understand that unless it CLEANS HOUSE, there will not be, anywhere in this section, anything of organized labor left.”[106]

Through its association with the violence in Centralia, the Central Labor Council was forced to disassociate itself from the tactics and ideology of the IWW. When the Central Labor Council acted to expel the Wobblies from its Seattle locals, participation in the purge came not only from conservatives, but radicals who had once been their allies.[107] In the wake of public outrage, most of Seattle’s labor radicals were quick to distance themselves, lest they be targeted next. Associated Industries’ advertisements ceased after November. The campaign had had its intended effect.

Conclusion

The struggle between labor and capital in postwar Seattle took place largely in the press and public imagination. Truth was not important. What mattered was the ability to persuade the public that the enemy did not have their interests in mind. It did not matter that the IWW were more often victims rather than perpetrators of violence if the public could be persuaded they were a dangerous movement growing strong by the day. The Central Labor Council was not able to effectively convey its message to a broader audience when Associated Industries controlled the terms of the debate. Rather than take employers to task for engaging in unfair employment practices or exploiting workers’ anxieties over food and shelter, it was forced to prove it was not revolutionary under criteria so broad as to include anyone who was opposed to the open shop.

The labor spies of Associated Industries were part of a larger national trend of repression against both the Left and the labor movement in general. Like traditional labor spies, they checked on the activities of union activists, and were well informed of who was organizing and agitating, and where they were doing it. They kept Associated Industries updated on the latest news and developing trends in the labor movement, allowing them to counter union and IWW activities. Associated Industries also ventured into the emerging field of propaganda, deliberately distorting and falsifying information which would be used to discredit labor and manufacture a threat that did not exist.

Copyright (c) Shaun Cuffin, 2014[1] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 13, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 27.

[2] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 28, 1920, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 8.

[3] Labor spy report by Agent #17, August 17, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 27..

[4] Minutes of the Northwest District Defense Committee of the IWW, September 28, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 12.

[5] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power: Consumer Organizing, Gender, and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1919-1929 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 25-26.

[6] Frank, Purchasing Power, 22.

[7] Frank, Purchasing Power, 23.

[8] William M. Short, “History of Activities of Seattle Labor Movement and Conspiracy of Employers to Destroy It and Attempt Suppression of Labor’s Daily Newspaper, The Seattle Union Record,” November 28, 1919, William M. Short Papers, Accession 4891-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, 2.

[9] Jonathan Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State, 1885-1935 (New York: Garland, 1983), 196-197.

[10] Frank, Purchasing Power, 25.

[11]Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State, 201.

[12] Frank, Purchasing Power, 95; “Frank Waterhouse & Company,” MarineLink.com, accessed January 31, 2014, http://www.marinelink.com/history/frank-waterhouse--company.

[13] Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State, 201-202.

[14] Vilja Hulden, “Employers, Unite!: Organized Employer Reactions to the Labor Union Challenge in the Progressive Era.” (PhD dissertation, University of Arizona, 2011), 14.

[15] Hulden, ”Employers Unite!,” 285-286.

[16] Francis R. Singleton, “Seattle and the American Plan,” leaflet reprinted and distributed by Associated Industries, 1920, Harry E.B. Ault Papers, Accession, 0213-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 5, Folder 17.

[17] Bulletin distributed by Associated Industries, 1920, Washington State Federation of Labor Records, Accession 0301-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 6, Folder 37.

[18] Richard C. Berner, Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration (Seattle: Charles Press, 1991), 302.

[19] Allen M. Wakstein, “The Origins of the Open Shop Movement, 1919-1920.” Journal of American History 51, (1964): 462-464, accessed December 29, 2013, http://jstor.org/stable/1894896.

[20] Short, “History of Activities of Seattle Labor Movement,” 15.

[21] Frank, Purchasing Power, 112.

[22] Frank, Purchasing Power, 95.

[23] “Personnel of Committee,” undated clipping from The Union Record, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 15.

[24] Richard C. Berner, Seattle 1900-1920, 303.

[25] “Building Owners Support American Plan,” advertisement in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 24, 1919.

[26] Bulletin released by Associated Industries of Seattle, August 23, 1921, Washington State Federation of Labor Records, Accession 0301-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 6, Folder 37; Roy J. Kinnear, Final draft of address to Associated Industries, 1923, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 7; Roy J. Kinnear, Letter to R.W. Felton, editor of The Seattle Star, March 15, 1924, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 2.

[27] R.L. Polk & Co., Seattle City Directory, 1919, F899.S43 S42, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[28] Robert M. Smith, From Blackjacks to Briefcases: A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003), 80.

[29] Jennifer D. Luff, “Judas Exposed: Labor Spies in the United States.” (PhD dissertation, College of William and Mary, 2005), 6.

[30] R. Jeffreys-Jones, “Profit Over Class: A Study in Industrial Espionage,” Journal of American Studies 6 (1972): 239, accessed December 22, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27553099.

[31] Smith, From Blackjacks to Briefcases, 88.

[32] Luff, “Judas Exposed,” 18.

[33] Luff, “Judas Exposed,” 40.

[34] Labor spy report by Agent #106, May 12, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 14.

[35] Draft Registration Card for Edward William Graham, 1942, Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards [database online], United States, Selective Service System, Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Fourth Registration, Records of the Selective Service System, Record Group 147, National Archives and Records Administration; Ancestry.com, Wisconsin, Births and Christenings Index, 1826-1908 [database online].

[36] Polk’s Seattle City Directory, 1917, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[37] Polk’s Seattle City Directory, 1919, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[38] Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census [database online], Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[39] Polk’s Seattle City Directory, 1920, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[40] Polk’s Seattle City Directories, 1921-1929, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[41] Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census [database online], Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Bureau of the Census, National Archives, Washington D.C.

[42] Polk’s Seattle City Directory, 1930, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[43] Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census [database online], Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, Bureau of the Census, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[44] 1940 United States Federal Census.

[45] 1940 United States Federal Census.

[46] “Edward W. Graham (1890-1956),” Find a Grave, accessed February 9, 2014, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=86918600.

[47] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 7, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 25.

[48] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 7, 1919.

[49] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 13, 1919; Labor spy report by Agent #17, August 17, 1919.

[50] Labor spy report by Agent #17, September 28, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 28.

[51] Labor spy report by Agent #17, December 10, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 1.

[52] Labor spy report by Agent #17, January 14, 1920, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 2.

[53] Labor spy report by Agent #17, September 9, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 28; Labor spy report by Agent #17, November 13, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 30.

[54] Labor spy report by Agent #17, January 21, 1920, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Box 2, Folder 2.

[55] Labor spy report by Agent #17, May 8, 1920, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Box 2, Folder 6.

[56] Labor spy report by Agent #17, June 28, 1920.

[57] Minutes of the Northwest District Defense Committee of the I.W.W., September 28, 1919; Labor spy report by Agent #17, September 28, 1919.

[58] Labor spy report by Agent #17, September 9, 1919.

[59] Financial Statements of Boilermakers Local 104, April-June, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 12.

[60] Labor spy report by Agent #106, April 30, 1920, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 23.

[61] Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State, 205.

[62] Labor spy report by Agent #106, April 30, 1920.

[63] Labor spy report by Agent #172, March 31, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[64] Labor spy report by Agent #172, March 12, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[65] Labor spy report by Agent #172, March 12, 1920.

[66] Labor spy report by Agent #172, April 2, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[67] Labor spy report by Agent #172, April 2, 1920.

[68] Labor spy report by Agent #181, March 10, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[69] Labor spy report by Agent #181, March 10, 1920.

[70] Labor spy report by Agent #181, April 2, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[71] Labor spy report by Agent #181, April 2, 1920

[72] Labor spy report by Agent #181, March 10, 1920.

[73] Labor spy report by Agent #181, April 2, 1920.

[74] Labor spy report by Agent #181, April 2, 1920.

[75] Labor spy report by Agent #317, March 11, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[76] Labor spy report by Agent #317, April 1, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[77] Labor spy report by Agent #317, April 1, 1920.

[78] Report by Operator C, March 19, 1920, Papers of Roy John Kinnear, Accession 0102-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 6.

[79] A search for “Wahke” on AncestryLibrary.com in Washington and adjacent states returned with six results, all from the 1910 United States Federal Census. Five of the people listed were members of a Native American family living on the Yakama Indian Reservation. The sixth person was a single Austrian immigrant living in Grant County, Washington.

[80] Report by Wahke, ca. 1920, Papers of Broussais C. Beck, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 2, Folder 10.

[81] Stephen Robertson, “The Company’s Voice in the Workplace: Labor Spies, Propaganda, and Personnel Management, 1918-1920,” Labor 10 (2013): 58.

[82] Associated Industries of Seattle, “Reference & Membership List of Associated Industries” in “Weekly Bulletin, 1920, Call #R381 As78W, Special Collections, Central Library, Seattle Public Libraries

[83] “Seattle and the American Plan,” Associated Industries Bulletin, 1920.

[84] Robert Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1964), 27.

[85] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 25-27.

[86] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 46-47.

[87] Labor spy report by Agent #106, April 30, 1920

[88] Financial statement of I.W.W. Bail and Bond Committee, August 25, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 27.

[89] Labor spy report by Agent #17, October 6, 1919, Broussais C. Beck Papers, Accession 0155-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle, Box 1, Folder 29.

[90] Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (Chicago: Quadrangle, 1969), 446-447.

[91] Albert F. Gunns, “Civil Liberties and Crisis: The Status of Civil Liberties in the Pacific Northwest, 1917-1940.” (PhD dissertation, University of Washington, 1971), 35.

[92] Hulden, “Employers Unite!,” 15.

[93] Ole Hanson, “I.W.W. New Name for Anarchistic Communism,” The Seattle Sunday Times, August 31, 1919, 71.

[94] “Ex-Soldier Employed On Dock Attacked and Blames Longshoremen,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 12, 1919, 1.

[95] “Hustlers to Get Encouragement. Training to be Offered Youths,” The Seattle Sunday Times, August 10, 1919, 9.

[96] “Organization of Industries Urged,” The Seattle Daily Times, October 1, 1919, 16.

[97] “The Harvest,” The Seattle Star, November 12, 1919, 1.

[98] “The One Big Boss,” The Seattle Star, November 20, 1919, 1.

[99] “The American Plan,” advertisement in The Seattle Star, October 30, 1919, 12.

[100] “To The Employers of Seattle,” advertisement in The Seattle Daily Times, October 31, 1919, 29.

[101] “Here is an Example of Threat and Intimidation as Practiced Under the ‘Closed Shop’,” advertisement in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 1, 1919, 10.

[102] “Seattle’s Declaration of Independence,” advertisement in The Seattle Star, November 8, 1919, 18.

[103] Associated Industries of Seattle, The Square Deal, Vol. 1 (Seattle: Associated Industries, 1919), Call #331.1 Sq. 23, Special Collections, Central Library, Seattle Public Libraries.

[104] “The Impending Strike of the Coal Miners,” advertisement in The Seattle Daily Times, October 26, 1919, 27.

[105] “America Must Clean House!”, The Seattle Daily Times, November 12, 1919, 1.

[106] “America Must Clean House!”, 1-2.

[107] Frank, Purchasing Power, 105-106.