Below are profiles of more than two dozen articles written for this project.

By Emma Kane-Galbraith

The General Strike was in its third day when six unions returned to work without the sanction of the

Central Labor Council. They were following the lead of the Street Car

Men’s Union, Local 587, which had voted to end its strike that morning. Most early-returning unions were conservative, well-established,

highly skilled craft unions, but the streetcar operators were not. Rather, the Street Car Men’s Union was new and its members were anxious to hold on to the few benefits they had recently accrued. Local

587 prioritized actions that would redefine streetcar operators from poorly

paid, unskilled workers into the higher rank of well-off “skilled” labor.

By Patterson Webb

The Seattle General Strike grew out of a strike in the shipyards that began in January 1919 when 35,000 workers walked off the job demanding a wage increase that federal officials had promised would be theirs at the end of World War I. This article explores the background to that strike, describing the shipyards that employed tens of thousands during the war, examining the working and living conditions of workers in overcrowded Seattle, and detailing the union negotiations that preceded the walkout. Separate from the article, here is is a database of 142 digitized newspaper articles about the shipyards during 1918.

By Patrick Farrell

While the city lay dormant, the mayor, city officials, union leaders and Henry Suzzallo worked day and night to find solution to the strike. Henry Suzzallo, however was not a city official or a labor leader. He was the President of the University of Washington, a president whose connections to state and federal leaders resulted in appointments to positions of more power and prestige. Governor Lister had landed him the powerful job of Director of the State Council of Defense during the war and bizarrely enough asked Suzzallo to fill his position as he lay dying during the strike.

By Jessica Keele

In the early years of the 20th century, waiting tables became a popular job choice for many of Seattle’s white, working-class women. Led by Alice Lord, waitresses organized Local 240, the first and longest-running waitresses’ union in the nation. Nineteen years later when over 60,000 members of 110 different unions stunned the country by joining together in a solidarity strike, Local 240 played a key role, working with the other culinary unions to feed tens of thousands of striking workers in improvised dining halls throughout the city.

By Senteara Orwig

The story of IWW "songbird" Katie Phar, a 10-year-old Spokane girl, and her correspondence with Wobbly martyr and songwriter, Joe Hill, brings to life the powerful synthesis of music and organizing that the IWW employed in the years before World War I when the radical organization was becoming influential in the Pacific Northwest.

By Shaun Cuffin

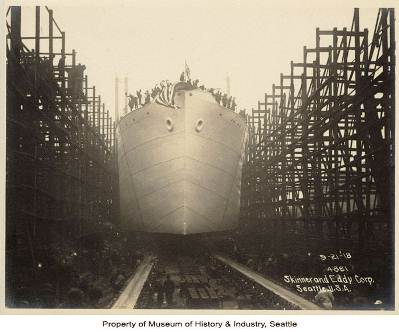

Edward W. Graham worked at Skinner & Eddy Shipyards, where he was a card-carrying member of Boilermakers Local #104 and Shipbuilders Industrial Union Local #325 of the Industrial Workers of the World. He was also a spy who sent daily reports to the leadership of Associated Industries, an employer group that led the campaign to defeat organized labor in the wake of the General Strike. This report uncovers the spies, explores their methods, and assesses their impact.

By Robert Cherny and Seth Bernstein

The Seattle General Strike of 1919 gave the city a reputation for radicalism, but even those familiar with the city's early twentieth-century radicalism are unlikely to know about the other radical Seattle--a highly successful agricultural commune in the southernmost part of Soviet Russia. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was often referred to as “the American commune. Its history provides an unusual chapter in transatlantic history and the international dimensions of US history and adds new dimensions to the history of immigration, the Pacific Northwest, and Soviet agriculture

By Kathryn Karcher

Described as one of “the greatest moments of working-class solidarity and militancy in American history,” Seattle’s 1919 General Strike demonstrates both the strengths and limitations of collective action in the labor movement during the twentieth century. Largely kept out of male-dominated spheres but racially privileged themselves, White women’s racist rhetoric and practices leading up to the General Strike played a crucial role in excluding Black and Asian American women from Seattle’s labor movement and thereby from the mainstream narrative of the General Strike itself.

By Rebecca B. Jackson

Anna Louise Strong begins her autobiography

I Change Worlds with a story about herself as a little girl wandering through a garden and realizing, for the first time in her short life, the powerful sensation of loneliness. For the grown woman writing her memoirs in 1935 this epiphany symbolized Anna Louise's steadfast, life-long dedication to a Socialist ideal that united all human beings in peace.

By Colin M. Anderson

To many of the locals in Seattle the strike was the beginning of an attempted revolution by the Industrial Workers of the World and others with similar radical tendencies. The insistence of these conservatives that the IWW was behind the strike, together with the state of the organization and its place in the labor movement at the time, has created a mystery as to just how much of a role the “Wobblies” played in the Seattle General Strike.

By Jon Wright

In relation to the African American community, the labor movement was anything but radical. Seattle unions were often racist and excluded Blacks from their ranks. At other times they voiced support for Blacks, but in actuality they did little to erase the color bar in unions. African Americans experiencing these racist attitudes developed an ambiguous relationship with labor, with some supporting and others opposing labor unions.

By Phil Emerson

For two decades, between 1901 and 1921, the International Shingle Weavers’ Union was one of the largest, most powerful unions in the Pacific Northwest. It set the standard for the other unions of the day or yet to come. Historian, Norman H. Clark described the Shingle Weavers’ as, “The most militant and articulate representatives on the Trade Council were the shingle weavers, whose union was by far the largest and strongest.” Every labor union in the state if not in the nation has benefited from the Weavers’ existence.

By Lynne Nguyen

Women have always participated in the labor movement of the Pacific Northwest, the type and extent of their participation was the key question asked about women's involvement in the labor movement. Although women have played many roles in the movement, the most long-standing and persistent role that women had was that of supporter of their union husbands. Many women workers learned how organization could increase their chances of successfully negotiating with employers for fairer wages and better working conditions.

By Sheila M. Shown

Several newspapers were in support of labor making certain advances. However, the Seattle General Strike was viewed to be something more. Labor was aiming to shut an entire city down and maybe even more. Some newspapers began to publish paranoia articles and to imply that the unions were pushing for a ‘Bolshevik Revolution’. These newspapers played on people’s fear of losing their democracy even though that wasn’t really the case.

By Nicolas Greenwood

The 1919 general strike hinged upon the question of electricity. Seattle survived the strike without incident, in large part due to the compromise achieved of electrical workers volunteering to keep the City Light plant running while other industries shut down. The two prevailing electrical workers’ unions in Seattle at the time, Local 46 and Local 77 of the IBEW, each played a significant role in the events surrounding the strike, though they could not have been more different from each other. Local 46 enjoyed a strength of size, organization, and purpose, while 77 was beset with trouble from affiliations with IWW and Bolshevik sympathizers, most notably the Wobbly activist Leon Green.

By Trevor Williams

Ole Hanson was Mayor of Seattle in 1919 when the Seattle Central Labor Council led local unions on a general strike that shut down the city for three days. When the strike ended promptly and peacefully, regional and national newspapers gave Mayor Hanson full credit for its conclusion, launching him on a short whirlwind of national celebrity. Because newspapers and he himself exaggerated his importance in ending the strike, and because at the moment of his prominence the public was looking for a man of his supposed qualities, Ole Hanson became an over-large target for near-fanatic praise from people all over the country.

By Susan Newsome

The combination of an increased fear of a possible German invasion and a strong patriotic duty among Americans led to the creation of volunteer organizations in which citizens could show their dedication to the United States by spying on their friends, neighbors and co-workers and reporting any un-American conduct.

By Erik Mickelson

Establishing lumber unions was a huge task, and even the few that did exist as part of the AFL and IWW had a hard time raising wages and improving working conditions prior to 1917. Usually, a majority of lumber workers would not want to strike; or if they did, the lumber company did not seem to mind sacrificing a few months of labor in order to maintain the upper hand in the lumber industry. World War I was the catalyst that helped change the face of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest.

By Chris Canterbury

The Northwest lumber industry in the early part of the 20th century was, at its best, rugged, at its worst, brutal. The isolation and transient lifestyle of timber workers made most of them unable to vote. With few ties so society and an insecure economic future, these men had little to lose. This disposed many towards unions or other forms of protest although they were rarely successful.

By David Radford

On Monday April 29 1918, a local branch of the Commercial Telegraphers Union held a small meeting in Seattle, unaware of the storm of controversy and political wrangling that would follow for the next four months and the shockwaves that would bring labor in Seattle ever closer together. The story of the workers struggle against the Western Union and Postal Telegraph Companies in 1918 embodies the social and political fragility of the times and the state of labor in Seattle in the year preceding the first general strike in US history.

By Stan Quast

Sentenced to death in 1917 for a July 1916 San Francisco parade bombing he was ultimately cleared of, Thomas J. Mooney in his San Quentin death row cell became the focus of an intense, desperate struggle by trade unionists and political leftists nationwide to thwart the California execution.

By James Larrabee

By the late afternoon of July 19, 1913 the Seattle headquarters of the Industrial Workers of the World lay in ruin. Along with two Socialist Party offices and a Socialist newsstand, it had been looted and its contents dumped into the street and burned by a mob of locals and visiting sailors.

By Tae H. Kim

Women had worked in textile industries and other industries as far back as 1880, but had been kept out of heavy industries and other positions involving any real responsibility. Just before the war, women began to break away from the traditional roles they had played. As men left their jobs to serve their country in war overseas, women replaced their jobs.

By Rutger Ceballos

A vocal and militant anti-war movement emerged in Seattle following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914. Based largely in the labor and radical communities, it continued even after the US declared war in 1917 and Congress passed punitive sedition laws. This paper explains the politics of prowar and antiwar activism in Seattle and details the government crackdown on dissent, including the prosecutions that sent Hulet Wells, Louise Olivereau, Sam Sadler, and others to prison.

By Ryan Deibert

Press coverage of the development and implementation of Washington State’s 1911 Workmen’s Compensation Act varied significantly from newspaper to newspaper. Particularly among Seattle newspapers, amount and slant of coverage and editorial opinion seemed to reflect the fundamental political and economic interests of the newspaper publishers and their intended audiences.

By Kimberley Reimer

Women who worked in the laundries in Seattle during the World War I period worked long, hard hours and were forced to work faster to receive less pay for their work. As laundry owners increased prices, they refused to pay more and fired women who joined unions or sought out representation. Nevertheless, women organized into unions and when their frustrations rose to a crescendo it culminated in a very successful strike.

By Chad Seabury

The construction of race in the United States has been a long process of redefining and reaffirming the ideas of whiteness and citizenship. This racialized form of thinking was by no means a forgone conclusion from the creation of our country, but was a thought process that was created and perpetuated over hundreds of years, continuing through today. The process of organizing labor was certainly not immune to racialized forms of thinking.