The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (Four L) grew to become the world’s largest company union soon after Brice P. Disque of the United States Army created it in 1917. However, the historical context surrounding World War I set up the preconditions favorable to the formation of this unique union. Before the United States could enter World War I, the nation had to build warplanes, ships, and barracks. This resulted in a tremendous need for supplies. With the booming wartime economy, labor was a prime commodity in 1917. However, in the years prior to 1917, there had been a surplus of labor. Workers had to put in long hours for measly pay and there were no paid vacations, no pensions, and layoffs were common. This contributed to a very unstable lower class workforce. Establishing lumber unions was a huge task, and even the few that did exist as part of the AFL and IWW had a hard time raising wages and improving working conditions prior to 1917. Usually, a majority of lumber workers would not want to strike; or if they did, the lumber company did not seem to mind sacrificing a few months of labor in order to maintain the upper hand in the lumber industry. World War I was the catalyst that helped change the face of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest.

The wartime economy of World War I required a hefty labor force in the United States. As a result of the increased demand for labor, loggers and lumbermen in the Northwest finally had the leverage to strike for higher wages and better working conditions in the middle of 1917. In this paper, Part I will illustrate how a disorganized, unpatriotic labor workforce united to work toward the general welfare of the United Sates, joining the lumber employer and employee into the world’s largest company union. Second, Part II will analyze how and why the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumber was able to draw the majority of lumbermen and loggers to work together for the common good of both the loggers and lumbermen in serving the United States. Part II will look primarily at the logging publications The Lumberjack and The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen Bulletin and explore the strategy, the image and message the Four L presented to loggers and lumbermen.

Part I

The Four L: The Origins of the World’s Biggest Company Union

The Lumber Strike of 1917

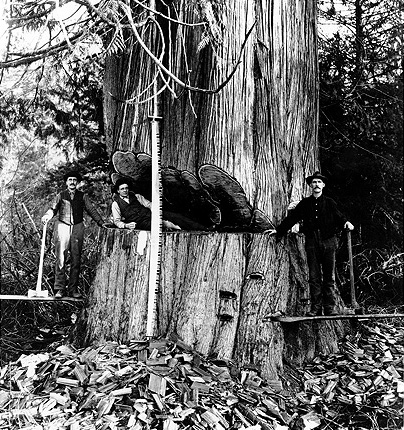

The Pacific Northwest was viewed as the final frontier in the continental United States at the turn of the nineteenth century. Loggers from the east migrated to the Northwest because the timber harvest was abundant at the beginning of the twentieth century. There was an abundance of land, an abundance of trees, and many men in the forests who helped make great profits for the employers. Companies such as the Simpson Logging Company, Weyerhaeuser, Long-Bell, St. Paul and Tacoma were the main logging companies and earned immense profits. Fredrick K. Weyerhaeuser owned so much land in the Northwest that the government investigated him for corruption; but due to the way land was sold in the region, the government could do nothing to limit Weyerhaeuser. Even though the employers (lumbermen) earned huge profits, they passed little on to the loggers. On average, the loggers made only 35 cents an hour working in wet and dangerous conditions. In addition, the working conditions in the woods were unsafe, unsanitary, and cooks subjected the loggers to food that was inedible at times. For example, the food was so wretched in one Northwest logging camp that one logger, A. Linquist killed the chef claiming that "God told him Ed Gosseling (the cook) was the devil." In logging towns, it was fairly common to hear of periodical work-related deaths occurring in the forests because conditions were unsafe and the trees and machinery were very unforgiving in event of an accident. Lumbermen did not want to sacrifice profits for the sake of safety. One logging camp close to Port Angeles had two separate, accidental logging deaths on the same day in 1915. Even though the majority of loggers were discontented with working conditions, there was little they could do to increase their wages or improve working conditions.

Prior to World War I, work was scarce, labor was in abundance, and the lumbermen knew it. Lumbermen exploited employees and did not worry whether or not horrible working conditions would drive them away. After working a ten-hour day in the woods, the "timber beast" (as the logger was commonly called) retreated to a blazing fire at the camp. In the camp, the logger had to share space with numerous pigs, (which were kept at all logging camps to eat food scraps). Even though outhouses existed, they were located 100 yards or more from the camp and were seldom used. As a result, the "timber beast" lived in an intensely unsanitary living environment. The typical year for a labor worker in the Northwest consisted of orchard and construction work in the summer and lumber in the winter. Thus, the low demand for labor and constant labor turnover prevented any real improvements in working conditions. As a result, the wages stayed low, the conditions unsafe, and the food bad.

In 1917, the United States entered World War I. With the booming wartime economy, labor turned into a prime commodity, establishing increased demands for all kinds of jobs in the country. The radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), organized in 1905, had already terrorized many other industries by encouraging strikes. The IWW quickly migrated to the lumber industry when they saw the leverage the logger had on the lumbermen due to the demands of war. On April 13, 1917, on the dangerous Montana waterways, what started out as a local strike for river workers quickly escalated to a series of strikes across the region by July. The IWW encouraged the loggers to go on strike for better wages and working conditions.

Before the emergence of the IWW on the lumber scene, there had been several lumber unions of the early 20th century. Nevertheless, all were short lived. One example was a fly-by-night promoter who created the Royal Loggers Union in 1906. He sponsored a Fourth of July picnic and collected union dues from hundreds of loggers. After the picnic, the promoter disappeared with the money—and the union went with him.

What separated the IWW from other unions was its organization and ability to bring together a union and organize a strike. The IWW created pro-labor propaganda in attempts to strengthen their union. In addition to trying to spread their beliefs, they demanded hefty stipulations when workers went on strike, breeding the hatred of employers. In Montana, the IWW asked for a wage raise from $3.50 to $5.00 along with a cut in the working day from 10 to 8 hours. In addition to striking, the IWW operated in an all or nothing strategy. If the hostile union did not get their way, they encouraged sit down strikes and sabotages when the workers went back to work.

As a result of all the work stoppages and violence, many people, including local authorities, employers, and even other unions such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL), were against the IWW. The AFL condemned the IWW for its un-American propaganda and tried to persuade everyone not to support or join the IWW. In Aberdeen, Washington, the AFL council "Condemned any interference with the bonafide unions of this city (Aberdeen) by the antagonistic union, un-American organization styling itself the Industrial Workers of the World." Three days later, the Central Labor Council of Seattle also denounced the IWW stating that "the IWW, by their radical methods, had succeeded in erecting an insurmountable wall of prejudice between capital and labor so far as members of that organization were concerned." The IWW had irritated a great number of people and organizations because of their intense antagonism and degree of success. It was highly successful at stopping work across the Northwest in the summer of 1917.

To understand the nature and significance of the IWW in the Northwest lumber industry, it is necessary to look at the demographics of their recruits. Many members of the IWW were migrant laborers or hobos. However, a smaller, yet significant number of IWW members were recruited from lower socio-economic levels of the settled workers. Such workers were naturally drawn to the closing words of the communist manifesto: "The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workers of the world, unite!" It was easy for the IWW to make headway amongst its men, shaping their ideas, tactics, and actions as they went along. As the rest of the population sacrificed for the general welfare of the country in the name of patriotism, most if not all of the IWW workers could have cared less. Harold Hyman wrote concerning this class difference in the United States, "The mob spirit, always close to the surface in America and now clad in patriotic garb, was merely accelerating a process of class cleavage that had long been under way . . . Patriotism was an emotion that ‘a bum without a blanket’ could hardly share." The Bulletin of the 4L described this problem frequently. Looking back on the strike, it wrote, "It was a complete industrial collapse, an orgy of loafing and plundering. A reign of horror." By the time of the 1917 lumber strike, this lack of patriotism was to be one of the hardest obstacles to overcome in an attempt to end the strike.

Preparing for War

When the United States entered World War I, it needed warplanes and ships to fight in Europe. As of April 1917, the U.S. had no airpower. However, it also lacked the raw materials to build a strong force. At this same time, the IWW was fomenting labor unrest throughout the Northwest and across the nation. The IWW created much trouble for the US Government hindering the process by which they could not get the needed supplies to build the warplanes, ships, and barracks for the war.

The US Government sought a solution to the problem of slow and inefficient war materials production caused by the actions of the IWW. They assigned Brice P. Disque to bring the lumber supply up to standards for the Army. An Ohio native, Disque had been a loyal supporter of the Army since the age of fourteen. After serving in the Philippines at the turn of the century, he climbed his way up the Army ladder as an excellent equestrian. In an assignment in Manila, which involved rebuilding a transport canal, Disque earned the reputation as being good with labor relations. Within six weeks of arriving in a foreign country with only 100 workers, he managed to recruit more than 2,000 civilian laborers to quickly finish the task. Using a bonus system, he motivated the workers to rebuild the canal instead of just minimally fixing it for the time being. Disque’s new assignment from the US government was to fix the lumber industry.

Spruce was the lumber the Army sought after the most. Spruce was the strongest, most flexible wood in the forest. However, it grew in patches and was relatively hard to find. Lumbermen primarily focused on Fir and Cedar, however they harvested Spruce as they came upon it. The US only produced 2 million board feet of Spruce a month before the lumber strike. They needed five times that amount to make the required quantity of warplanes, ships and barracks, and this did not take into account lumber for private interests. Companies did not want to expand spruce production because spruce was scarce. However, when they did find it, the price was so expensive, they made huge profits and the extra profits were seen as an extra bonus. Thus, when the entire lumber industry went on strike July 1, 1917, it made an already bad situation even worse for the United States Army.

Though Disque held antiunion sentiments, he did sympathize with some of the logger’s desires. Disque said, "All sides were selfish and neither shows any patriotism" The United States had a half billion directed toward warplanes for the war, yet it could produce a sparse amount of aircraft because of the lumber strike. Disque soon realized that both the loggers and the lumbermen were both determined to win the strike. The task he began to undertake was much bigger than he anticipated. He could not do it all himself.

When Disque realized that the lumber dispute would require a great deal of help, he recruited several key figures onto the scene of labor relations. The first was Carleton H. Parker, a mediator. In the years preceding 1917, Parker had mediated over 24 work stoppages. This leading Progressive agonized employers when he said workers received a "niggardly" wage. Parker supported rational economic capitalism and a broad based political democracy. He integrated economics and sociology into his mediation. One of the keys to his success in mediation was his ability to get both sides to meet face to face. Parker’s philosophy was neither pro-employer nor pro-employee; rather he was for equal profit sharing in a democratic fashion at all costs trying to avoid strikes. Parker saw strikes as a complete waste of time and money for both sides and as an event where both sides always lost.

A field representative of the Council of National Defense named I.A.B. Scherer was also brought in to help fight the battle against the IWW. Scherer, an anti-wobbly, was Disque’s first mentor in labor-management relations affecting the Army. Scherer’s anti-union views had a considerable impact on Disque’s initial attitudes concerning the pattern of unionism in the Northwest.

In addition to Parker and Scherer, Disque contacted University of Washington President Henry Suzzalo. Suzzalo was attractive because of his good reputation among business owners and because he was respected due to his position at the University. When Suzzalo took Disque up on his offer, he mortgaged his academic future because the lumber controversy polarized people. Hyman wrote, "Nothing in the state and in the Northwest region was more sensitive than the lumber strike and the eight-hour issue. Because Suzzalo never forgot that his state unit was designed to serve the national council and the nation’s interests, he was willing to risk his academic future and the postwar political career he coveted." By jumping into the labor issue, Suzzalo adhered to his convictions, but jeopardized his career. Suzzalo, Scherer, Parker, and Disque met regularly in Suzzalo’s University office to strategize how to end the labor strike. Meanwhile, the lumber strike was just beginning to snowball.

The End of the Lumber Strike of 1917

As the lumber strike dragged into the autumn and it continued to gain even more momentum. At first, it looked as if a contingent of small lumber companies, two major unions (AFL and IWW), and stubborn lumbermen would never unite on a common platform. On August 15, 1917, Washington governor Lister proclaimed the 8 hour day with 9 hour pay in an attempt to end the strike, it looked like the end was near. However, the lumber workers did not approve of it and on September 1, the IWW switched from an open strike to a strike on the job. It was at this time that Parker changed his plan. Instead of focusing on the Wobblies demands, he decided to focus on the discontented workers. Parker arrived at the idea of government ‘monitorship’ or ‘stewardship’ of the logging industry. He did not want government ownership, but rather as a means of bringing the two sides together so they could work out their differences. Parker had a goal of creating a working environment where men would want to work, and the experienced logger would labor at full steam rather than malingering over what the government needed.

In the meantime, the government needed spruce for the war. On October 10, Disque was forced to send an unskilled Army into the woods of the Northwest to try to obtain lumber. They accomplished just as little as the lumber workers who were striking on the job since they did not know what they were doing. To circumvent this problem, Disque created several regiments by drafting and hiring unemployed lumber workers. The soldiers formed a labor pool and upon requests from ‘approved’ lumber companies, the soldiers would fill in the gaps where civilian labor was inadequate. Not only did this break the strike, but also if any Wobblies decided to cause any trouble, there were soldiers as a police unit to keep the peace.

After breaking the strike, Parker set about designing some way that the bitterness between the employers, the AFL, and the IWW could be glossed over. Parker thought the only way for all sides to get along was for everyone to come together and form a legion. Thus, on October 18, 1917, Parker, along with Disque, in the office of the president of the University of Washington, gathered to establish the foundation of what was to become the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen.

The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen Become a Union

For a union of both employers and employees to come together and work for the common good, there had to be numerous compromises combined with various tactical actions. First, the union founders had to circumvent public disapproval that the government was financing soldiers to work for private interests. Parker and Disque came up with the idea of a woodcutters division in the Army. Disque’s recruited loggers joined this new division in the Army. Next, Disque came up with the idea of a name for the division. Part of his strategy was to bring all sides together in one group and to not use the word ‘union.’ He hoped the title, "Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen" would be an organization everyone could rally behind in a spirit of patriotism for the general welfare of the United States.

Disque toured the region rallying support for the Army’s newly created Legion. He proved to be a very effective speaker and instinctively adept at industrial politics. Wobblies, AFL men, loggers, and lumbermen all liked him. More importantly, they accepted Disque as a neutral mediator in the labor dispute. By October 25, Disque met with a committee of lumbermen whose total invested capital worth exceeded $24 million. Disque convinced both sides to head back to work with the one and only concession being the 8-hour workday. At the time, the 8-hour day was not much of a concession on the lumbermen’s part because the fall days were getting shorter and the loggers could not work long summer hours. When the loggers went to work, Disque gave each logger a "good-looking certificate of membership (to the 4L) and a characteristic emblem to wear." Disque, Parker, Suzzalo, the lumbermen, and the state’s AFL head, Marsh, all reviewed the terms of the 4L. After agreeing on the terms, all members of the Four L went to work aspiring to log enough lumber for the United States war time effort.

Part II

How the World’s Biggest Company Union Conducted Business

Even with the creation of the 4L and the end of the lumber strike, the lumber industry at full force could not produce the amount of spruce needed for war materials with the current number of loggers in the workforce. At least 38,000 skilled workmen were needed to log the region during a period of average public demand. To produce the amount of spruce the United States needed during the war, a workforce of over 100,000 was needed. However, the total number of workers of the Army and Four L, had fallen far short of this number. An immediate, pressing concern of Disque was the recruitment of new loggers.

Disque levied the help of a local lumber magazine called The Lumberjack to spread the news of the need for labor help. The Lumberjack, a lumber publication based out of Seattle headed by the Spruce Production Division, submitted articles from fellow loggers and lumbermen on the happenings of the region. Disque had convinced the division that the Four L interests would be positive for spruce production and they joined with Disque in the cause. In the January 1918 issue, the feature article was headlined, "Large Amount of Lumber Needed." Even though the title of the article did not come across as urgent, the content of the article read, "the necessity for an adequate production of ships is the most serious matter that now confronts us in this greatest crisis in our country’s history, or in the history of the world." The Lumberjack helped plead the case for the Four L. The Four L needed workers and needed them immediately.

Advertisements and articles promoting the need of laborers in the region ran in The Lumberjack until mid-summer in conjunction with Disque’s own recruitment. By August 1, 1918, the membership of the Four L had grown to 110,000 and by December the whole lumber community was praising Disque as the man who brought the industry back to full working order. The Lumberjack wrote that the legion was a "cure for radicals," and that the Northwest would never forget Brice P. Disque." Not only had The Lumberjack helped Disque attain his labor quota, but continued to praise the new union in hopes of continuing the prosperity that had come to the region in the form of a healthy working community where logger and lumbermen worked together.

The Four L continued to gather strength over the following years even after the lumber strikes had come to a virtual stop. It did not grow in size, but the prosperity it brought to the lumber industry was a testament to the mutual effort of both logger and lumbermen to work together. The Lumberjack and the Four L bulletin both presented the issues, ideals, and the plan of the union and helped the Four L grow stronger by focusing on community, communication, and education.

The Anti-Wobbly Union’s Quest to Build the Perfect Community

Even before the establishment of the Four L, lumbermen despised the IWW because the Wobblies encouraged work stoppage, sabotage, and violence. The lumber strike of 1917 was a testament to the strength of the IWW. However, when the Four L was created, though the majority of the members were loggers, it was a union of anti-Wobblies. The loggers who joined the Four L had to be anti-wobbly, and if they were still in the IWW or had sympathetic views towards the IWW, they were not hired. For the Four L to be successful, it had to be a community. The central focus of the Four L community were ideals of democracy, equal rights, and patriotism.

The Bolshevik Revolution inspired many workers around the world, even in the Northwest. The Four L would have nothing to do with Bolshevism though. In the lead story of their February bulletin, the Four L bulletin published a speech by Disque called, "Industrial Peace Means Square Deal." Disque spoke to the crowd stating that the Four-L was a legion only for pro-Americans. He said, "We have heard all about the pro-German, the pro-French and the pro-English, but the time has come when everything said in this country must be for the ears of pro-Americans only." Disque believed that the ideals that the IWW held were brought in from outside of the United States and the only way to maintain American prosperity was through nativism and patriotism. The cartoon in figure II shows a woman swatting an IWW fly, while in the distance a larger swarm of insects threaten of Bolshevik, Sedition, and Anarchy. The message of this cartoon was that if a person was not a committed supporter of Americanism, foreigners would eat the cake of American prosperity. Disque expanded his view saying, "Therefore, if we will come together to discuss our problems, and if the man who regards himself as a laborer sits with one whom he regards as an employer, and they get together fairly, they ought to come to the same conclusion regarding a given problem." The solution for Disque and the Four L for solving labor unrest and squashing the IWW was community, a very tight knit community with homogenous views regarding nationalism, prosperity, and anti-communism

Anti-Wobbly sentiment worked well in establishing a community because it built the foundation of a community where everyone had similar views. Not only did the legion eliminate the radical Wobblies, but it also continued to persecute all wobbly pretenses through the middle of the 1920’s. The homogeneity of views sanctioned by the Four L made it much more likely to reach compromises on issues and not rely on strikes to settle disagreements.

Though anti-wobbly views were prevalent in the Lumbermen and Four L bulletin, other strategies were also used for building community. Many pro-society projects were taken on by the Four L to boost support and give the members in the legion a cause to work behind. In the April 1919 issue of the Four L Bulletin, it published an article describing the attempt of the legion to improve hospital service by getting rid of the contract doctor. Previously, the employer made a contract with a doctor or group of doctors. If a logger was hurt on the job or in need of treatment, the logger had to go to a specific doctor and had no choice of his own. If the new plan was enacted, the logger would have either an unrestricted free choice of any doctor he wanted to see, or at least an organized free choice where he could visit with a doctor that was part of a larger association of doctors. Even though switching to a plan where loggers could chose their own doctors would cost lumbermen more, the Four L Bulletin supported the idea. It wrote, "This is undoubtedly a step in the right direction." By carrying through with this idea the legion would demolish the monopoly of service some doctors enjoyed, and lessen the amount of "scamped work" done by negligent doctors.

In addition to improving the way doctors were selected, the Four L also helped build both a brand new hospital and a new store for the use of its members. In 1925, in the city of Shelton, the Four L with the Simpson Logging and Peninsula Railway donated $25,000 to build a brand new hospital. The area around the city previously had not had a hospital and loggers had to travel great distances to get any major medical care. In North Bend, the Four L also started a grocery and supply store built for the sole purpose of offering cheep goods. The store, owned by 200 individuals who each invested $10 to get started, offered any member of the Four L the opportunity to purchase goods in the store at 10% above cost, a savings of 40%. The store in its first month of business turned a profit and saw more than $5,000 in capital. By helping its members acquire a choice for doctors, a new hospital, and a reasonable place to buy food and supplies, the legion helped raise the sense of community of those in the Four L. With each project that the Four L tackled, it strengthened the legion that much more.

Communication

The Four L realized that a necessary trait in aiding the community at large was their effectiveness of communication. Just as Disque communicated to the people of the Northwest that the United States needed a large number of loggers to help supply the country for war through the Four L bulletin, the Four L continued to communicate to its members important events, happening or decisions that took place through this same method. From community events to the implement of new and safer equipment, the Four L bulletin was the means through which the Four L communicated.

The Four L bulletin discussed the important issues facing the legion every month, but in addition, at least half of the articles reported minor events effecting the community. The Four L was very proud of the new and improved mills it helped improve and construct. When the new Weyerhaeuser Mill in Everett, Washington, opened, the bulletin bragged that it was "one of the finest lumber manufacturing plants in the world." It was essential that the legion communicated the advances taking place in the region. Though certain local logging mills had not been updated yet, reporting such events encouraged mill workers to adapt advancements taking place to the local community. In figure III, the new mill in Everett is displayed as the owners bragged how they paid "real money for certain new features in its mechanical department." Before the legion, the lumbermen used to do whatever was possible to save capital. Whether it was new mills or recreation halls, the Four L bulletin portrays the lumbermen as wealthy owners who wanted to brag to each other through the buildings that they can make for the loggers. In Sandpoint, Idaho, the Humbird Lumber Co. built a new club and recreation house with a "splendid recreation room, two women’s rooms, dainty decorations, one large room especially for children, a music platform, and a gymnasium equipped with basketballs, horizontal bars, trapezes, etc." By constructing recreational facilities to let the loggers enjoy themselves, the lumbermen felt they would work harder on the job.

The bulletin also let the loggers know about the ultimate end product of their labor. During the war, there were monthly photos and articles on the bay legionaries who turned out the vessels built out of the Northwest Spruce. The article read, "the five-mast sailing vessel, 240 feet long, 46 wide, and 20 foot hold . . . is 100% 4-L and 100% loyal." The Four L thought the loggers would work harder and feel better about their work if they knew where the wood they were harvesting was headed.

The Four L never missed an opportunity to communicate with the legion the good it was accomplishing and its benefits to its members. In the March, 1919 issue of the bulletin, the Four L responded to grievances about the lack of pay and minimum salary. It explained that though the minimum salary for one day of work was between $4.40 and $6.70 an hour (depending on the job), the going wage was $1.10 higher and their wages would be raised accordingly if they worked hard enough on the job. The Four L continued to answer its critics that the Four L stole the labor ideas from the IWW. The legion said concerning the eight-hour-day, "What’s the difference, so long as the 4-L is keeping it?" Whether it was recreational or had to do with salary, the communication between logger and lumbermen helped prevent many unnecessary disturbances and work stoppages. While the Four L was the third largest union in the state of Washington in 1919, it was 24th out of 29 unions in the number of strikes in that year. This statistic verifies that the Four L successfully opened the lines of communication between employer and employee.

The Role of Education and Motivation

"The sluggard will not ploy by reason of the cold; therefore shall he beg in harvest." Proverbs 20:4—reprinted from the Lumberjack, January 1918.

The Four L viewed education as a means of improving production. If the Four L was to give loggers an 8 hour working day, the loggers would have to be more productive to achieve the same amount of production of lumber for the lumbermen. By educating and motivating the loggers in the ways of the forest, the legion believed the loggers would become better and more efficient workers.

The Four L’s views toward labor were very similar to the teaching in the book of Proverbs. The book teaches if a man does not work, he does not deserve to reap in the harvest. The ideal of a genuine work ethic was one of the many values the Four L tried to instill upon its workers. There were always many quotations from the Bible to motivate the loggers in The Lumberjack. The Four L bulletin was similar. In each issue, the bulletin would publish poems and sayings from loggers and lumbermen that were supposed to inspire the individuals. One saying read, "For nature is a magnet and a lure that draws you closer as you learn her way, she lends you strength and patience to endure and teaches you life’s lesson day by day." Not only did the Four L promote hard work, their proverbs and sayings also directed the logger toward education.

In addition to moral teachings, the Four L repeatedly pointed out to the loggers all negative facts of strikes. In a coal mining strike in 1919, their workers only received 25% of their actual request which was a huge "net loss" considering the miners were on strike for 40 days. The Four L said, "there are over 150,000 men who went on strike in the 2nd quarter helping to increase the cost of living." The legion insisted that strikes only bred more trouble and the righteous thing to do was to help educate the rest of the public through peaceful ways of negotiating without the loss of work.

The legion did not only educate the loggers morality and propaganda surrounding strikes, it also attempted to communicate a successful business strategy. In a feature article, the legion explained that a successful business could not spend all of its profits on more labor because it needed capitol as well. The pro-lumbermen article said, "Capitol is neither moral nor immoral," and explained how the companies would do whatever was in their means to improve the wages of the workers who helped harvest the lumber.

In figure III on page 26, a photograph from The Lumberjack was reprinted showing eight different trees and the loggers sitting beneath them. The Lumberjack ran a promotion offering ten dollars to the first man to correctly identify the eight different varieties of trees illustrated. The quote in the contest read, "A regular Lumberjack ought to be able to tell at sight any of our Northwestern trees." Though it is a friendly contest with a decent reward, it symbolizes the importance the lumbermen placed on education and knowledge of the forest. Though the minimum salary of a logger was low, there were several examples in the publications of loggers who started at entry level positions and through hard work and education worked up the ranks of leadership to a higher paying position with better pay.

The bulletin’s efforts toward education were not only directed at the logger, it also aimed in the direction of the lumbermen as well. In an article titled "What I expect of my employer," a logger explained the traits of a good lumbermen from the viewpoint of the logger. C.H. Hoffman, the logger, said he wished lumbermen were more cooperative and hoped they would take the initiative toward a personal relationship with them. If this happened in Hoffman’s logging camp, he said he would be more passionate and willing to work, especially for fair pay. Hoffman stated, "the employer is beginning to wake up because of the Four L." The Four L continued its campaign to educate both logger and lumbermen so each could become more empathetic toward one another. In the large scheme of events, each side would learn how the other worked and how they could work together more cooperatively.

When All Was Said and Done

In 1938, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen memberships had diminished to the point that it folded. At the end of World War I the legion boasted a membership of 110,000 members; however, it slowly lost steam. The lumber industry enjoyed tremendous prosperity in the twenties due to the cooperation of both logger and lumbermen; but in the 1930s, the Great Depression weakened the lumber industry tremendously. Lumber mills closed down and thousands were unemployed. Even the cooperation between the employer and employee could not save the legion. For the twenty years the legion existed, it became the largest union in the world in which both employer and employee worked together for the benefit of the industry. In the time of war, the Four L brought an end to the Lumber Strike of 1917 and produced enough spruce for warplanes, vessels, and barracks for the United States. What originally was a government sponsored union to bring lumber to the Army matured into a highly powerful legion where cooperation, prosperity, and community were the main thought of its members. The Four L was a testament at how employer and employee could prosper if the two worked together for a general cause.

©1999 Erik Mickelson

SOURCES

Harold M. Hyman, Soldiers and Spruce: Origins of the Loyal Legion of Loggers & Lumbermen (University of California, Los Angeles, 1963)

Claude W. Nichols, Brotherhood in the woods; the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, a twenty year attempt at "industrial cooperation." (Thesis-University of Oregon, 1959)

PRIMARY SOURCES

This report will describe three sets of primary sources that would be useful to researchers investigating the 4L and the Lumber Strike of 1917.

Brice P. Disque papers, 1917-1960, ms 67002231

Over two boxes of original papers from Disque. Most of the papers are personal, but there are some business papers from his days in the 4L. note: the majority of the papers from his time in the 4L are kept at the University of Oregon.

Four L lumber news, 1919-1937, 674.05 FO v.1-19

Issued three times a month for the life of the Four L, this is a wonderful source for articles and happenings of the Four L. The earlier issues display anti-IWW propaganda and illustrate the prosperity that possibly could happen if employer and employee enter in to an equal and non-exploiting relationship.

Industrial relations in the west coast lumber industry, Cloice Ray Howd, 1923, 979.714 H83i

Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics which has many labor statistics and numbers of the Four L.