Women have always participated in the labor movement of the Pacific Northwest, the type and extent of their participation was the key question asked about women’s involvement in the labor movement. Although women have played many roles in the movement the most long-standing and persistent role that women had was that of supporter of their union husbands. One way that women demonstrated this role was through their involvement in the Seattle Card and Label League, while many have not acknowledged their importance to the movement, Kathryn Oberdeck and Dana Frank have successfully argued that the importance of the supportive role of women, and the AFL’s inability to use them in the movement was what led to the eventual failure of the movement. But with their entrance into the once prohibited male work place because of the need for men on the frontlines of World War I, the role of women in the labor movement evolved to one where they were given the opportunity to participate more. There were many reasons for the change in the role of women but the most significant was that many women workers learned how organization could increase their chances of successfully negotiating with employers for fairer wages and better working conditions.

Armed with the knowledge that their increased participation in the movement could improve their working conditions, many working women soon came to see the necessity for more active roles in the movement. Although more participatory roles were desired by some women workers, the male leaders of the unions and the American Federation of Labor, which was the key governing body of all the unions in the nation, did not accept women in these increased participatory roles. But, despite the male resistance to women becoming more involved in the movement, women’s struggle for more involvement eventually succeeded. This can be seen in several ways in the Pacific Northwest, the development of the subjects written for women in the women’s section of the Seattle Union Record, as well as the support that Seattle’s women barbers got in forming their own local union, and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Worker’s recognition and support for the telephone operators were all examples of women’s increased involvement in the labor movement. In addition to these developments in women’s roles in the movement, the importance of the Seattle Card and Labor League and its’ ability to persuade women to buy union labeled goods illustrated the necessity of the women’s supporting roles to the movement.

The entrance of women in to the workforce during World War I posed a challenge to the labor movement. Because of the void left by soldiers women were asked to enter into once exclusively male occupations such as taxi drivers, machinists, and ship yard workers. Although women were praised for "responding nobly in taking the places of men forced to leave their positions to do work essential to the industries" as well as "for applying for work merely as a patriotic duty", they were still not permitted to join the unions of their new occupations. Since union scale was only paid to union members, women in these positions were paid less than men for the same jobs. Because women were affected financially by their inability of to join unions, they learned early on the importance of organization.

It was this frustration at being paid less than men were for the same jobs, which led many women workers to want to organize. Women began to learn "that it is only when they do get together in organizations, and bargain collectively" that they would be "entitled to the same industrial opportunities" as men. Thus, they started believing that the only way that they could improve working conditions and get better wages was by coming together in unions the way men did. While this idea would seem to be popular and supported by all working women, there were some who "were not interested in the working class problems" of their fellow women workers. The lack of support for the right of women to organize by other women hampered the already difficult fight women workers faced in trying to organize. While there are several reasons why many worker women did not choose to support this fight, the most often cited reason for women’s the lack of support was that women workers saw themselves as temporary workers. Thus by viewing themselves as temporarily in the workforce, the need to change conditions seemed less important since they would not be in the workforce for long.

In addition to being paid less than men, the lack of attention given to their problems as working women was another reason that women believed in the necessity of more participatory roles in the labor. Once reason that many worker women advocated the increased participation of women in the movement was because a majority of the cases that came before the National War Labor Board involved "large numbers of women workers". It was because of this that the Women’s Trade Union League believed that it was "both a matter of justice and of necessity" to have "a women’s viewpoint represented in the membership of the war labor board". The need to have female representation on the board was necessary since women’s cases made up a large majority of the cases that the board ruled on. Thus, by having female representation on this labor bureau, women’s point of view were heard and discussed by the board, which would eventually result in better working conditions and wages for women.

In addition to bothering women, men were also frustrated by the inequality between the wages women and men were paid for the same work. Since women were paid less than union scale, males in the workplace saw them as a threat because they would work for less money than union workers would. This would give them an advantage over men in the work place when it came to getting jobs as well as keeping jobs during hard times in the economy. It was this frustration over women’s advantages in the workplace that led many men to support their fight to organize. Many men believed that the exclusion of women from unions made women threats the union scale since they were willing to be paid less than men were for the same jobs. While most men believed non-organized women workers were a threat to the union scale, most did not publicly acknowledge this. Yet there were a few who were willing to publicly go on the record about this issue. One example was from 1918’s May 30th issue of the Seattle Union Record, where one man stated that "union men realize that it is the underpaid women who really takes away their job, breaks down the conditions, they work for". The Ruth Ridgway column of the Seattle Union Record was another arena where men discussed how they felt about the issues concerning working women. One example comes from the May 31, 1918 column, where a male union worker advised women workers that "when you take a job, be sure it’s fair and demand a man’s wages for a man’s work". Many men may have had unselfish reasons for supporting women worker’s in their fight to organize. They viewed unorganized women as a threat to their livelihood since they were losing jobs to them. It was the perceived threat that unorganized women posed to them that led many men to support women workers.

While many union men supported the right of women to organize, the vast majority of men did not. There were several reasons for this; the first was that they believed that the income those women earned at these jobs were not necessary to theirs and their family’s survival, but were instead used for luxuries in their everyday life. Since it was believed "that women were only working for pin money" and did not need to work to survive, the importance of equal wages and safe working conditions for women workers were not seen as important. Based on this belief that women were not working for the livelihood of their family, the belief that women could leave their jobs at anytime also hampered them from getting support from men. Thus, by perceiving that their working was a only done for extra cash and not for survival, men’s beliefs on the importance of the needs of women workers were decreased. Since men did not believe in the importance of women earning equal pay as men, the also did not believe that it was important for women to join unions, which was the only way possible for women to get equal pay. Thus by putting little importance on the need of women to earn equal wages, the belief in their need to organize was implicitly displayed.

While the belief that women only worked for spare cash was one reason why many men did not support women in their fight to organize, many also believed that the majority of women workers, who were young and unmarried were not worth organizing because they believed that these women viewed themselves as temporary workers. The belief that women were only working until they found husbands went along with labor leader’s beliefs in the temporary nature of the single woman worker. Men publicly argued in favor of this belief in newspapers. One example of the discussion men had about single women workers came from the Ruth Ridgway column, where one reader wrote that "women are harder to organize than men, because they are not interested in job conditions, but in getting away from the job and marrying". Because of the perception that women workers were only temporary to the workforce, men’s beliefs in the importance of equal wages as well as better working conditions for women decreased.

The involvement of women in the labor movement has not always been promoted or accepted, but despite the lack of support that women got in their fight to have more participatory roles, they did eventually gain a more influential and powerful role in labor. The evolution of the women’s section of the Seattle Union Record, the locally owned labor paper was a good illustration of the evolving role of women in the movement. Since the paper was owned by the unions, the development of the women’s section along with the articles written for women makes this paper more insightful, because it gives you a reliable portrait of how the leaders in the movement viewed women and their role in the movement. The magazine section of the paper, which was known as the unofficial women’s section of the Seattle Union Record, was first created in 1909. While one would expect for this section to appeal to the woman worker since it was labor owned and ran, it did not ever fully appeal to this audience. This can be explained by what the leaders believed the role of the women worker should have been. At the time of its’ creation women were expected to be supporters of their union men, not personally involved in the movement. But with time and the development of the women worker and her increase role in the movement, the paper evolved to appeal to her concerns while still appealing to the earlier audience of the union housewife.

From the Magazine section’s conception it had been directed towards the wives of union men. Because of this cooking, fashion, and household tips were perceived to be the central issues discussed in this section. The emphasis on these topics was displayed throughout the columns that were published in this section. The most explicit example of the newspaper appealing to the housewife was with the "Our War Garden" column. This column had many tips on how to can and preserve produce grown in ones’ garden to how to start ones’ own garden. The subjects written about in this column came from letters sent in by readers. Although one may reason that the newspaper did not direct this column at housewives, that it was the women who wrote in to this column asking for advice, that in reality were directing this column, this would be an incorrect explanation. Instead the title of "Our War Garden" clearly displayed what type of audience that the newspaper was appealing to with this column. That being the homemaker that had the time to make the most out of their garden in the wartime where household products as well as produce were scarce. Thus by giving advice to women on how to make the most of their gardens, this column was also advising them how to become better homemakers through the use of their gardens.

In addition to the gardening column of the Magazine section, the fashion tip column also was directed towards the housewives of union men. The fashion tip column consisted of a photograph and a small description about the fashion trend of the time. The fashion tips given in this section were rather varied. They advised women about what types of fabrics were the most fashionable to make their clothing out of to what angle hats were to be worn to be in fashion. The "My Husband and I" column written by Jane Phelps was another example of how the newspaper in its’ Magazine section appealed to housewives and their problems. The key topic of this column was the ideal relationship between a husband and wife. The column began describing a problem that the wife had about something the husband had said or done to her, but instead of getting angry at the husband the wife would resolve the problem by changing the ways she viewed what had happened and the importance that she had given to the incidence. An example of the meek manner that this column advocated for women comes from 1919’s August 6th issue of the Record where Susan Randall, the main character of the column describes how her mother in law disrespected her by ordering her around her own home. But instead of expressing her anger to her husband Tom about her mother in-law "coming into her home and ordering…her around" and demanding that Susan call her mother, Susan decided to keep it to her self and to give in to her mother in-law "for Tom’s sake". This example from the column displayed how the author used the universal issue of the mother in-law to appeal to housewives. In addition to using the sore topic of mother in-laws, the name of the column also was used to appeal to housewives. By creating something in common between the reader and subject of the column, the author blatantly displayed whom she was hoping to attract with the column.

The magazine section of the paper also included articles and poems written by women. The most famous of female author to write for this section was Anna Louise Strong the famous reporter, who was known for her unflagging support of the labor movement, and later on of communism. Quite unusually Strong, who was the most famous of all women writers for the Seattle Union Record, only wrote about women’s issues under her pen names of "Anise" and the lesser known one of "Ruth Ridgway", which was researched and written about by Rebecca Jackson. The reason for this has never been fully explained, but one can reason that she did not want to lose her credibility with her male colleagues by writing about women’s’ issues. For someone who did not publicly acknowledge the importance of women’s issues except under disguise, the strong support Strong had for women in the labor movement was quite surprising.

Strong used two types of media; her poems and the Ruth Ridgway column to display her support for working women. Strong wrote poems about the problems that working women experienced under her pen name of "Anise". Strong’s poem "What Women Shall Wear" was a good example of the issues that she discussed in her poem column. In this poems she explained how women working in furniture factories decided to start wearing the male attire of overalls to work "because it was dangerous for them to wear loose clothing near machinery" in addition to being against the law. But instead of supporting the women for being brave enough to wear men’s clothing, the other women of the town "protested that overalls were immodest". This poem displayed many of the issues that working women were faced with, their need to adjust themselves in order to work in the new work place, and also the criticisms they faced by other non-working women. By writing about the difficulty that many working women faced in the workplace as well as by others who were not involved in the workplace, Strong helped increase the support that working women got by making their plights public.

In addition to using her poems to gain sympathy for women workers, Strong used her Ruth Ridgway column to gain support for women workers. She did this by printing letters or her responses to letters that defended women workers. An example of this was from the 1918’s May 18th column where one reader responded to the allegations that women were taking jobs away from married men who needed those jobs to support their families. The reader pointed out in her response to these false accusation that "single men compete with married men" and for the most part these men "have no one to look after except themselves" while women who work are generally married and had "one or more than one dependent upon them". By printing this response that defended women and their right to work, Strong was displaying her support for them. While the bulk of Anna Louise Strong’s writings were about societal issues, the support she gave women in the labor movement through her work done in her pen names were important to gaining support working women.

But with the growing participation of women in the labor movement, the scope of this section began to change. While it kept many of its’ original columns about gardening, fashion, cooking and the relationships between husbands and wives to keep appeal to its’ original audience, which was mainly housewives, it also added new columns in order to appeal to a new audience, the working woman. One of these new columns in the Magazine section of the paper was the "Club Notes" column, which began in early 1920. This column was a daily journal of what happened at the local women’s meetings. It reported on who held which positions in the clubs as well as what issues were discussed at the meetings. By writing about women and their the Seattle Union Record appealed to a different type of reader, by displaying its’ interest in non-housewife women’s issues. By drawing attention towards the women’s unions and clubs that were in their creation made to fight labor causes, the union was trying to diversify their audience to encompass labor women as well as housewives as well as attract the women worker for their readership.

The Seattle Union Record also created the "For The Worker Women" section to appeal to worker women. The articles written in this section of the paper were usually more directly related to the working woman than any of the other articles written for women. It usually consisted of articles related to the involvement of women in the labor movement in Seattle as well as the rest of the world. The topics of the articles ranged drastically. Some articles were filled with discussions about how much involvement women should have in the movement, while others introduced and applauded famous women for their contributions to the cause. While the "For the Worker Women" section of the newspaper was a huge development in the evolution of the paper treatment of worker women and their concerns, it was not a total change in how the editors viewed women. This was illustrated through the placement of articles on fashion, beauty, and how to be a better homemaker printed on the same pages of the "For the Worker Women" section. The placement of these contradictory portrayals of women along side each other on the same page of the paper displayed the Seattle Union Record’s weak support for the working women. By printing these articles in such close proximity to each other, the Record was implicitly illustrating its’ belief that the role of the worker woman was not independent, but was instead dependent upon her role as a homemaker.

While the evolution of the Seattle Union Record’s attention to working women and their concerns were easily observable, the reasons for why its’ focus evolved was more difficult to explain. One rationalization could be that the newspaper modified its’ focus from the housewife to the working women and the housewife in order to gain a larger total audience for their paper. It was good business sense for the Record to appeal to many types of readers instead of conforming it to one specific audience. That was why the "For the Worker Women" section was such a success for the paper, it gave them a whole new outlet to write about working women’s issues so that they could gain this reading audience. Thus, by following the progress of women workers as well as their roles in the movement, and then modifying the newspaper based on how women’s roles changed, the Seattle Union Record illustrated the development of women in the labor movement.

The development of the role of women in the Seattle labor movement can also be illustrated through the observation of the Seattle women barber’s union local number 1. The successful battle that these women fought in order to gain the right to organize displayed the increased participatory role of women in the labor movement. Although there were several reasons why the women barbers needed to organize, the chief reason for organization was financial. Because union members were advocated to only do business with shops that displayed the union card, female barbers lost business because they were "unable to display the union card". Since union cards were only available to members of the Journeymen Barber’s International, which was the national union that barbers belonged to, the women owned barber shops were unable to gain these union cards, thus impairing them from doing business with union workers.

Instead of losing business because of their sex, women barbers decided to try to get the international to let them join the union in order to stay in business. While they tried various means of gaining membership in the international, none worked. But despite the failure of their attempts to become a part of the international, they did not give up. They instead enlisted the support of their male counterparts, to show the international the legitimacy and support they had for their cause. While one may expect that the women barbers had little support from the male barbers, one could not be more wrong. The male barbers were their biggest supporters, they publicly stated in the Seattle Union Record that "they are in no way opposing the unionization of women". Some barbers even went so far as to "declare that they will patronize the women regardless of whether they are denied the use of the union shop card by the international". Even further than just publicly supporting the women barbers, some male barbers went against the international and helped women barbers organize a separate local. In addition to gaining and using the support of their male counterparts effectively, the women barbers were also able to earn the support and the endorsement of their union from the Central Labor Council of Seattle, which was the key governing body to all unions in the Seattle. The Central Labor Council decided to recognize their unions as long as they agreed to "maintain the same wages, hours, and conditions as those of men barbers, women barbers are to be granted full recognition and shop cards will be issued to them". This decision by the Central Labor Council went directly against the International’s decision to refuse a charter to the women barbers. By gaining the support of the council and the male barbers for their cause and by causing them to go against the international, the women barbers illustrated their increased role in labor.

The female telephone workers were another group that displayed the changes in women’s involvement in labor. While the difficulties they faced in order to organize were similar to the women barber’s problems, they also faced new problems that the women barbers didn’t. The belief that these women viewed their jobs as temporary hindered them from organizing. Since it was believed that these women would leave the workforce as soon as they married, the need for good wages and safe working conditions were not seen as important for these women. Even some of the individuals interested in helping telephone operators organize believed this. An example of this came from the 1918 September issue of the Seattle union Record, where a leader for the telephone operators stated that due "to the constantly shifting personnel of the company’s operators, the problem of organizing them…is a hard one". While fighting off their critics about the nature of their employees was more than difficult enough, the added criticism from their leaders did not help the operators fight for organization, but instead hindered it. In addition to battling negative stereotypes of about their workforce, the operators also had to fight the telephone companies in order to be able to organize. Many new "girls were secretly influenced to stay out of the union" and given preferential treatment if they complied with the wishes of the company. The telephone companies were so adamantly against the operators organizing that they were known to "used every trick known to the telephone business to make it uncomfortable for union operators to remain at work" in order to keep others from following their lead and joining the union. But despite all of these challenges they faced in organizing, they joined the Electrical Worker’s Union local 42-A and were recognized by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the union’s governing body in the summer of 1915.

Although union recognition was important to the telephone operators, it was the support that they got from the union brothers that was the most significant to them. The support that the men of the union gave the operators was quite impressive, instead of discreetly helping the women in their fight to get better working conditions and wages, the male union members publicly demanded the that the operators be treated more fairly. This was seen when a male union member "called on organized labor…to assist the Brotherhood of the Electrical Workers…in molding public opinion against the conditions complained" about by the telephone operators. By asking the public to help him and other male union members to help the operators, the support given to these women by their union was displayed. In addition to publicly supporting the women, the union also let them hold positions in the union, which at the time was quite unheard of. Although women had regularly held offices in women’s unions, the election Margaret Whitten for the financial secretary position was the first case of a woman holding office in a "regular man’s union". The union’s public support of the telephone operators as well as a woman’s successful bid at a position for the union both displayed the increased involvement that women had in the labor.

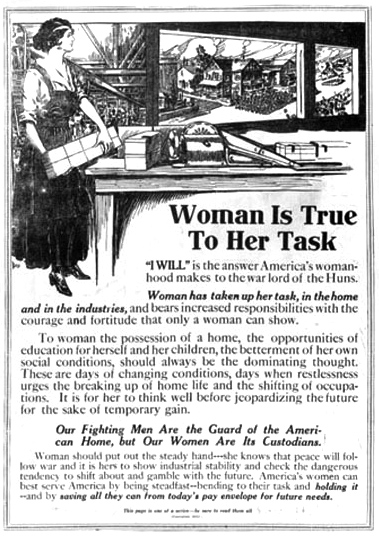

While the roles that women were asked to play in the movement did change significantly, the role of supporter to the union man did not change. Even when women began to gain an increased participatory role in the labor movement, they were still asked to support their union men. This was seen numerous times throughout the early twentieth century, yet the most common time during this period when this was advocated was during times of great stress to the movement. The Seattle General Strike of 1919 was a classic example of this. While many female unions such as the telephone operators union and the garment worker’s union voted in favor of striking to support the shipyard workers, the absence of any mention of these unions in the articles describing who participated in the strike displays the belief in the insignificance of these unions’ participation in the strike. Instead importance was given to the need for women to support their striking union men. Women were not asked to protest in the actual strike, but were instead told to stay in "their proper role as wife and mother in the home". They were also asked by labor leaders to "stand by your man in this, his hour of trial". While it was a generally men who advocated the supportive role of women in the strike and in the movement, there were some instances when women advised other women to play a supportive role in the strike. A poignant example of this was from a wife who wrote to the Seattle Union Record and advised women to "above all things, stand by your man, approve him openly. He’s working for you and he needs every ounce of encouragement you can give him in the struggle". This article also asked women to put up a brave front for her striking man since "nothing disheartens a man more than a despondent rag of a woman, and nothing heartens one more than a brave, reliant, resourceful one. The presence of women that promoted other women to hold supportive roles during a time of crisis, such as that of the Seattle General Strike displayed that men were not the only ones to advocate the supportive role women in labor. By asking women to stand by their man labor leaders as well as many women displayed the importance they put upon the role of the supportive woman. The absence of any mention about women personally taking part in the General Strike implicitly illustrated the disapproval and insignificance labor leaders had for women who participated in the strike.

The Seattle Women’s Card and Label League was another example of the supportive role that women played in the movement. From its’ creation the Card and Label League was meant to model the supportive role of women in the labor movement, chiefly because who its’ members were and its’ intended purpose. The organization consisted of the wives of local labor leaders. The goal of the organization was to persuade women to buy union crafted merchandise. The Card and Label League carried out its’ goal by hosting parties where they persuaded women to buy union made products. While the teas and parties the league hosted were often criticized as nothing more than a means for them to socialize, the league was successful in increasing women’s support of the movement. Since the league persuaded women to participate in the movement by buying union made products and not by actually protesting, the league was performing supportive function to the movement and its’ leaders. Because of this many commented on how the league was more beneficial to the movement than it was the woman’s movement". Although this organization was successful in its’ attempts to get women to buy union made products, it hampered the women becoming involved first hand in the movement by serving the movement in a supportive fashion.

While the purchase of union goods may seem a small contribution to the labor movement, it was in reality very important to the labor movement. Many felt that this was the most significant contribution that women could make to the movement. Since women were the principal shoppers for their families, the successful persuasion of them to buy union made goods was extremely important for the success of the labor movement. If labor was successful in persuading women to buy only union made goods, it could use the importance of their purchasing power to negotiate with big business in order to get better wages and conditions for workers. Many leaders in the AFL stressed to women that purchasing union made goods was the only way they should help out the movement, which further displays the supportive role that labor leaders promoted for women. Leaders in the movement advised men to "induce the home women to spend the wages of their men in the support of union labels" since it was the "most important addition to the strength of labor’s cause". While still reinforcing the supportive role of women in the labor movement, leaders explicitly pointed out their importance to the fate of the movement. The importance of convincing women to buy union goods was further illustrated when a Women’s Trade and Union League was created by the SCLC to emphasize the importance of only purchasing union goods, and establishing businesses with shop cards. Thus, by creating a new organization for the purpose of increasing the sale of union goods, the leaders of the labor movement displayed the importance of buying union goods for the success of the movement. The importance put upon buying union goods also displayed the significance of women and their supportive roles in the movement.

While women in the Pacific Northwest did achieve more participatory roles in the labor movement, the importance of their supportive role in the labor movement did not diminish. It instead withstood, and remained a powerful and highly necessary role for women to play in the labor movement. The importance put on their purchasing union labeled goods displayed the necessity of this role to the movement. Although some women did remain in supportive roles, this was not true of all women. Many forged more participatory roles for themselves in the movement when necessary. This was especially true of the women barbers of Seattle and the telephone operators. The women barber’s successful use of the support that they received from Seattle’s male barbers as well as from the Seattle Central Labor Council to form their own union, despite the opposition they got from the Journeymen Barber’s International in their request to organize. To encompass these new types of union women into their readership, the labor owned Seattle Union Record started to create sections for these women, while still keeping its’ earlier magazine section for women who chose to hold a more supportive role to the movement. Thus, by keeping the women’s section as well as creating "For the Worker Woman" section, the record was appealing to the two dominant types of roles that women played in the labor movement of the Pacific Northwest.