Early in 1919, as World War I was grinding to a close and revolutionary movements were sweeping Russia and Germany in the war’s aftermath, the nation was stunned and exhilarated by a strike in Seattle, Washington that brought the city to a complete standstill. Sixty thousand Seattle workers walked off their jobs on Thursday morning, February 6, joining the tens of thousands of shipyard workers who had struck two weeks earlier.[1] Before the four-day strike had run its course, the eyes of the nation had focused on Seattle, and the search for a face to put on the event had begun in earnest.

Authorities pointed fingers at “anarchists and radicals in the unions,” and ended their search there. The commercial press was similarly hostile. It is in the pages of the partisan labor press, The Seattle Union Record, that the human side of the event can be seen and its history traced. As the official voice of the Seattle Central Labor Council, it was also eyes and ears for Seattle workers in the weeks leading up to the strike. The paper was no small presence; the February 4, 1919 press run was 71,400 copies.[2] An opportune expansion from weekly to daily publication the previous year was to provide not only a vital link between the trade unions, but also a rich historical timeline of how the general strike developed. The picture that emerges is that of a remarkable social solidarity movement that traces directly, almost without interruption, back through several months to a nationwide fight by labor to save the life of Tom Mooney.

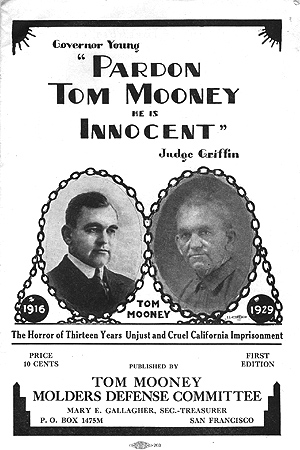

Sentenced to death in 1917 for a July 1916 San Francisco parade bombing he was ultimately cleared of, Thomas J. Mooney in his San Quentin death row cell became the focus of an intense, desperate struggle by trade unionists and political leftists nationwide to thwart the California execution. Later probes of the prosecution revealed widespread corruption and perjured testimony in the service of targeting “anarchist troublemakers.”[3] But Mooney remained on death row in a countdown to the gallows, as the efforts to secure a new trial were refused. By November of 1918, when the U. S. Supreme Court was asked to intervene, the plight of Tom Mooney was widely known throughout the West and in union locals across the country.[4] It was a union movement fired by urgency that only an unjust death sentence could sustain.

Even as the date approached for the Supreme Court review of Mooney’s appeal, huge rallies were being held in New York and San Francisco with the demand that he be freed and urging “industrial action” to enforce it.[5] The execution had been stayed by California Gov. Stephens pending State and U.S. Supreme Court reviews, and now was scheduled for Friday, December 13. The Seattle Union Record, now a daily newspaper with a growing readership in the community beyond the subscribing trade unionists, covered every action taken nationwide in Mooney’s defense. When the Supreme Court declined to hear the case on November 18, 1918, claiming lack of jurisdiction, attention was focused on Gov. Stephens and the demand for a pardon or a new trial.[6]

From this point forward, “Free Mooney!” would dominate the headlines and daily coverage in The Seattle Union Record, and guide the actions of the Seattle Central Labor Council, for the next one hundred days, leading right into the heady days of the Seattle General Strike. The urgency of the Mooney campaign, and the overarching themes of working class solidarity, internationalism, personal liberty and simple fairness that infused the Mooney fight, flowed seamlessly into the January dispute in the Seattle shipyards that triggered the general strike. Defiant messages from the condemned prisoner were given prominent airing: “The highest courts of the land…have said that a corrupt district attorney can use perjured testimony and can conceal and suppress material evidence to convict an American citizen…and that a citizen so convicted is without remedy…. Then they wonder why some workers become infected with Bolshevism.” [7]

Seattle unions wasted no time in beginning to organize for the final countdown. With less than three weeks until the scheduled execution in California, the Seattle Central Labor Council rushed to consider the way forward. By the time the council met the night of Wednesday, November 20, several member unions had already voted “in favor of a nation-wide strike, as a last resort, to obtain justice for the condemned man.” [8] The Machinists’ Hope Lodge, an influential craft union within the Metal Trades Council in Seattle’s shipyards, had passed a resolution calling for a national strike December 1. As with nearly every subsequent strike vote by Seattle’s unions, it passed by a large majority.[9] The next night the Metal Trades Council adopted the strike and sent it on to the Seattle Central Labor Council for its Wednesday night meeting, asking that “action taken be centralized and universal.”[10] After a unanimous vote, the Central Council recommended the general strike plan to all its member unions, three days after the Supreme Court issued its decision.[11]

Important undercurrents of industrial unionism moved just beneath the surface of these sympathy strike votes. Coordinating actions between local craft unions was already difficult---there were some two hundred unions in Seattle, dozens in the shipyards---and the cumbersome nature of craft organization in the face of real crisis was becoming painfully obvious to many in the labor unions. Along with passing the first general strike resolution, the Hope Lodge of Machinists also called for the amalgamation of all the shipyard trades into one industrial union.[12] The argument followed that actions taken in the shipyards should be decided by a mass vote of all shipyard workers rather than equal votes cast by each separate union, regardless of size. This move would prove decisive in the looming shipyard dispute, which shut down the Seattle waterfront and lead to the General Strike. Hampered by the American Federation of Labor leadership, but anticipating amalgamation, the Seattle Metal Trades unions had begun to act like an industrial union, fostering solidarity and enabling quick action. Seattle unionists saw themselves in the forefront of the drive for union amalgamation, with Kelly of the Machinists declaring: “When constitutions are against human rights I say to hell with constitutions. I think Seattle should take the lead and show the rest of the world we’re really for this principle.” [13]

Seattle was hardly alone in organizing for resistance. In San Francisco, where tensions also ran high because of waterfront disputes with the shipyards and government imposed wage scales, local unions in Oakland, San Francisco and Alameda were voting on Mooney strike proposals, with more unions to follow before December 1.[14] New York unions were preparing for industrial action on Mooney’s behalf; numerous demonstrations against the scheduled execution were ongoing.[15] Seattle, though, had taken the lead, with more local unions voting to strike and preparations proceeding at full speed in the Central Labor Council. The “splendid action of the Seattle trades unionists” was duly noted in a report from San Francisco, acknowledging that “their prompt and decisive action heartened the defense forces and gave wonderful impetus to the strike movement…sweeping the nation and arousing interest even across the Atlantic.” [16]

In the midst of this organizing frenzy, political bombshells were exploding that intensified the fight for Mooney’s freedom. Accusations that the San Francisco prosecutor had cynically rigged testimony to frame and convict the targeted “radicals” had resulted in an investigation by the U.S. Secretary of Labor. The telephones of the prosecutor were wiretapped in an elaborate undercover operation by J.B. Densmore, Director General of Employment, producing months of incriminating conversations by corrupt San Francisco authorities, and suggesting that California Governor Stephens would just as soon see Mooney hanged. The Seattle Union Record crowed that “almost every social and political act of those who are arrayed today as the principals in this amazing trail of guilty circumstances…has been preserved through the medium of the dictaphone.” [17] Excerpts from Densmore’s lengthy and accusatory report began showing up in newspapers November 26, further inflaming the outrage over Mooney’s now “proven” innocence.[18]

On November 22, the actual trial judge in the Mooney case, Judge Franklin Griffin, who had sentenced Mooney to be hanged, publicly called for a new trial, because of new knowledge of perjured testimony that had been presented to convict the defendant. In a letter to Gov. Stephens, Judge Griffin reviewed the entire body of evidence and concluded that Mooney had been unjustly prosecuted and convicted. The judge appealed to the governor to issue a pardon and grant a retrial. The Seattle Union Herald, for its part, demanded to know how the governor could maintain such a cowardly silence in the face of blatant injustice. “The hour is ripe,” the paper declared, “for Governor Stephens to let the world know whether he is a MAN or a POLTROON.”[19]

Across the nation, momentum for a general strike was building. In city after city local unions took near-unanimous votes in support of Mooney. New York, San Francisco, Milwaukee, Detroit, all took big votes in favor of a nation-wide general strike and began to make preparations for carrying it out.[20] British workers were concerned: A November 27th conference of the National Labor Party, attended by 1576 delegates from 352 labor groups voted unanimously to ask U.S. President Wilson to intervene on behalf of Tom Mooney. The London Trades Council was following suit.[21] Noted American writer Upton Sinclair wired the governor:

If you permit Mooney to die, you accomplish two results: First, you greatly weaken the influence of President Wilson with labor and Socialist forces abroad, upon which he must depend for the support of his program of international justice; second, you make almost impossible a peaceful issue of the impending struggle between labor and capital in America.[22]

Others got into the act. The King County Democratic Club found their own rationale for requesting conditional pardon or retrial: “The hanging of Tom Mooney will tend to provoke social discontent and disorder, and to break down popular faith in the orderly processes of the law,” [23] and sent this message to the governor. In Aberdeen, Washington, the Electrical Workers of Grays Harbor printed and were distributing circulars by the thousand, which read: “Labor has been very patient in this matter and every opportunity has been given for justice to prevail. But patience has now ceased to be a virtue, and action is our only recourse…”[24]

Not least, the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, had been writing to Governor Stephens imploring him to use his pardon powers to prevent the execution. Wilson’s concerns were simple: the post-war conundrum of “certain international affairs, which his execution would greatly complicate.”[25] These letters, beginning in March 1918, were kept secret by the governor; two weeks before the scheduled hanging, he had still not responded.

In Seattle, “a complete tie-up” of all industry was predicted for December 9, the date of the general strike, and organizers foresaw a city “engulfed in the silence of the tomb.”[26] Every union in the city was in solid support save the printers. James Duncan, head of the Seattle Central Labor Council, had wired to all labor organizations in the country asking participation in the general strike. “Grim preparations” were being made by the Central Council, providing for fire protection, food provisions, medical treatment and policing of the city.[27] Planning was comprehensive: The public safety committee even laid plans “to eliminate, as far as possible, the activities of the ‘blind pigs’ where the striking men might get the stuff that would blind their reason and encourage disorderly conduct.”[28] Seattle would be ready for the strike.

On Friday, November 29, Governor Stephens abruptly announced the commutation of Mooney’s sentence from death to life in prison. In a rambling defense of his decision and indecision, Stephens revealed the requests made by President Wilson to avoid roiling international affairs with a needless execution. In denying Mooney a pardon or new trial Stephens argued, absurdly, “the logic that a man is either guilty or innocent, and that necessarily if the maximum punishment is not justified pardon should follow does not hold either in theory or in practice.” Then, after refusing “to recognize this case as in any fashion representing a clash between capital and labor,” Stephens went on to attack Mooney as an agitator with anarchistic tendencies, and quoted some propaganda to demonstrate it. He made no mention of the prisoner’s innocence or the perjured testimony.[29]

Tom Mooney’s supporters were outraged. Mooney himself made a public statement from his cell at San Quentin refusing the commutation; he insisted on his innocence and demanded a new trial.[30] The Seattle Union Record protested that the cowardly decision left “the real question untouched,” that of an innocent man convicted on perjured evidence. “WE MUST HAVE JUSTICE,” the paper demanded, “if the wheels of industry must be stopped indefinitely.”[31] The next day, labor leaders in New York announced continued agitation for the nation-wide general strike set for December 9. The Seattle Central Labor Council proceeded with plans for the feeding of thousands of people during the strike. Minneapolis was ready to stay out indefinitely to win Mooney’s freedom. Three hundred thousand New York workers vowed to support the strike, and petitioned President Wilson to press for a new trial.[32] Riled up Canadian workers in Vancouver and Victoria declared their intention to walk out December 9 in support of Mooney’s freedom. Angry San Francisco rank and file workers were planning to defy their reluctant leaders and join the general strike.[33] The Seattle Union Record continued to print in large bold type in a box at the bottom of its front page: December 9.

On December 3rd, just days from the still-growing walkout, the International Workers’ Defense League in San Francisco, which had been coordinating the Mooney defense effort, called on supporting unions to postpone the planned strike. Instead, unions would send delegates to Chicago January 14th, to a Mooney Labor Congress that would plan the general strike and broaden its support. The extra time would allow for the Dunsmuir expose to be publicized. And the support of Samuel Gompers and the American Federation of Labor could be enlisted.[34] Such was the hopeful thinking that accompanied the collapse of the Mooney general strike, on the same day that the Armistice to World War I was being signed in Paris.

The labor council in Seattle, “where the general strike movement had been the strongest in the country with practically every local union ready to lay down tools on the date set,”[35] struggled to put a bright face on the postponement of the strike. While calling off the action and asking all local unions to select delegates to the Mooney Congress, labor council leader James Duncan expressed confidence that “if the strike had been called in Seattle on December 9 it would have tied things up as tight as ever a city was tied in history.”[36] Dunne embraced the reasons for the postponement, trusting in the judgement of the Workers’ Defense League that the general strike could be made more effective with better preparation. The labor council fired off a request to Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor that the A.F.L. take charge of the general strike proposed by the Chicago Mooney congress. Seattle unions set about selecting delegates to the congress set for January 14.

By the time in mid-December that James Duncan was chosen to represent the Seattle Central Labor Council at the Mooney congress, a reply had already been received from the A.F.L. “No strike of any character” would be supported by Gompers or the Federation.[37] The Mooney Defense League meeting in Chicago would remain outside the mainstream of organized labor. Still, expectations were high for “the largest convention of the rank and file of labor ever held.” Seattle unions would be sending as many as fifty delegates to join thousands of others in Chicago. Dunne and the Seattle council were hopeful that the congress could also deal questions of industrial unionism, international solidarity, freedom for other political prisoners, and reform of the A.F.L.[38]

Hidden in the intense focus on the Mooney struggle were the contentious negotiations in the West Coast shipyards. On December 10, the many various unions that formed the Metal Trades Council united to overwhelmingly pass strike authorization for the Council to invoke against Seattle shipyards, should the negotiations fail to bring a living wage to lower-paid workers. The Seattle craft unions had essentially become a broad industrial union on the waterfront. While dozens of Seattle delegates from the Metal Trades unions were preparing to go to Chicago, thousands of their members were growing angrier over unfair collusion between the shipyard owners and the government Macy Board. Leaders of the waterfront unions would be returning from the Chicago congress to an increasingly tense situation in the shipyard standoff. Seattle workers remained primed and ready for general strike.[39] The New Year’s Day headlines in the Seattle Union Record outlined three modes of action to be proposed in Chicago: demands for federal intervention, corrective legislation in California, and the strike.[40]

James Duncan, traveling through San Francisco January 12 on his way to Chicago, sought to confer with leaders of the International Worker’s Defense League and to persuade recalcitrant San Francisco labor leaders to join the congress and the fight for Mooney. There he visited Tom Mooney in prison, and reported back to the Union Record that “since shaking his hand and looking him squarely in the eye, I am now convinced of his innocence.” [41] Four days later, with the Chicago congress in its final contentious day, the Metal Trades Council in Seattle unanimously voted to set the following Tuesday, January 21, as a strike date if the wage issues could not be resolved. The issue was fairness: as put by A.E. Miller of the negotiating committee, the increase offered the higher paid mechanics “was nothing more or less than a sop to make them desert the poor devils who were hardly getting enough to exist upon.”[42]

The Mooney Congress was, in fact, contentious. The only thing readily agreed upon was to call for the removal of Samuel Gompers as leader of the A.F.L. There were fights over procedure, conflicts over accreditation, contests over broadening the program beyond the simple Mooney strike issue, squabbles over who would chair the meeting. The biggest fight took place over the timing of the proposed Mooney general strike. One faction, of which Seattle delegates were a part, wanted to capture the current momentum and set the date for May Day. The dominant faction insisted on postponing it until July 4. Fiery argument continued to the closing session where debate was cut off in an abrupt adjournment. The Seattle Union Record reported January 18 that “Puget Sound delegates held an indignation meeting after adjournment, and many delegates left the meeting bitterly resenting the action” of the congress chairman. At the close of the congress, W.E. Dunn of Butte, Montana, editor of the only other daily labor-owned newspaper, spoke for those pushing for a May first strike date: “This general strike is revolution. It strikes at the power of the courts. The world today is living on a powder magazine. Something may happen any day in this country which will arouse the employers of labor to the real dangers that confront them.”[43]

Three days later the “powder magazine” erupted in Puget Sound, when 45,000 shipyard workers walked off the job. “All reports indicate that the strike has been called absolutely ‘clean’,” announced Miller of the Seattle strike committee. “The men have walked out en masse and none have remained at the plants.” [44] In Tacoma, 15,000 shipyard workers walked out and were not shy; on Day Two of the action, Tacoma workers sounded the call for a general strike.[45] In Seattle, where 32,000 workers had left the shipyards “standing silent and deserted,” [46]the Metal Trades Council followed Tacoma strikers on Day Three with its own call for general strike. On January 22 it requested the Central Labor Council to set a general strike date for as early as February 1, and to “call the strike when the referendum carried.”[47] By January 24 the first unions were voting unanimously to support the strike. Cooperative grocery stores controlled by shipyard unions pledged to counter actions by the Retail Grocers’ Association to cut off credit to striking workers, and to provide food for all.[48] On January 28, the Seattle Central Labor reported that a majority of unions had voted to join the general strike, and immediately set about planning for the action. In one week, the shipyard strike had exploded into the “first general strike ever called in the United States”, now barreling toward a deadline of Thursday, February 6, 1919.[49]

When the wheels did stop turning in Seattle that Thursday morning in a historic display of labor solidarity and cooperation, that singular event was rightful heir to the passionate drive for justice that inspired the fight to save Mooney’s life. The remarkable timeline that linked the two events provided the historical opportunity for the two struggles to blend into each other. Seattle’s “first general strike in U.S. history” may have not played out as it did were it not for the enormous momentum of the Mooney campaign, the extraordinary confidence and resolve of Seattle labor leaders developed during the frustrating struggle for justice, and the support within a Seattle community alarmed by the personal injustice of the Mooney case. A strike for wages was informed and elevated by a higher calling. And we should not underestimate the value of preparedness. Having “rehearsed” the general strike right up to Mooney’s execution date less than eight weeks earlier, Seattle’s aroused workers were ready to act as one.

Footnotes

[1] “Wheels stop turning”, Seattle Union Record, January 6, 1919

[2] “Strike inevitable”, Seattle Union Record, January 5, 1919

[3] “Dictagraph exposes Mooney persecutors”, Seattle Union Record, November 26, 1918

[4] “Mooney case chronology”, Seattle Union Record, November 18, 1918

[5] “New York peace parade is featured by Mooney plea”, Seattle Union Record, November 13, 1918

[6] “Where will Mooney get justice now?”, Seattle Union Record, November 18, 1918

[7] “Tom Mooney confident that a great wrong will be righted”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 19, 1918.

[8] “All labor asks is a square deal”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 20, 1918.

[9] “Hope Lodge would strike to aid Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 19, 1918.

[10] “Mooney strike favored by Metal Trades”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 20, 1918.

[11] “Central body votes strike for Tom Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 21, 1918.

[12] “Miller would democratize Metal Trades”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 19, 1918.

[13] “Mass vote of Metal Trades may be taken”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 21, 1918.

[14] “Pacific coast is wrought up over Thomas Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 21, 1918.

[15] “Labor is aroused throughout East”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 21, 1918.

[16] “Labor rallying to support of Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 22, 1918.

[17] “Facts that lead to Fickert exposure.” Seattle Union Record, Nov. 26, 1918.

[18] “Iniquitous plans are exposed by government men”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 23, 1918.

[19] “What will Stephens do?”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 22, 1918.

[20] “Sentiment in favor of big strike grows?”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 26, 1918.

[21] “British labor back Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 27, 1918.

[22] “Sinclair uses his influence”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 25, 1918.

[23] “Bourbons ask Stephens to free Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 23, 1918.

[24] “Electricians help Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 25, 1918.

[25] “Stephens plays cowardly part”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 29, 1918.

[26] “Seattle labor gets ready for Mooney protest strike”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 28, 1918.

[27] “Seattle ready to strike for Tom Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 28, 1918.

[28] “Mooney strike plans laid by Labor Council”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 30, 1918.

[29] “Mooney given life sentence”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 29, 1918.

[30] “Martyr says he prefers death to life in prison”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 29, 1918.

[31] “It is not enough, Governor Stephens”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 29, 1918.

[32] “Nation-wide strike is now contemplated”, Seattle Union Record, Nov. 30, 1918.

[33] “Canada will join in the Mooney strike”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 2, 1918.

[34] “Mooney strike may be held in abeyance”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 3, 1918.

[35] “Mooney strike is deferred”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 5, 1918.

[36] “Labor council will call off the walkout”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 5, 1918.

[37] “Duncan chosen delegate to Chicago meet”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 12, 1918.

[38] “U.S. labor to show power on January 14”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 17, 1918.

[39] “Labor going in thousands to convention”, Seattle Union Record, Dec. 31, 1918.

[40] “To consider best way to help Mooney”, Seattle Union Record, Jan 1,1919.

[41] “Tom Mooney innocent, says James Duncan”, Seattle Union Record, Jan 13,1919.

[42] “Council votes for strike next Tuesday”, Seattle Union Record, Jan 17,1919.

[43] “Stormy scene marks end of Mooney meet”, Seattle Union Record, Jan 18,1919.

[44] “45,000 men out in Sound cities”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 21, 1919.

[45] “Tacoma strikers contemplate drastic action”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 22, 1919.

[46] “Response to strike call amazes the shipbuilders”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 22, 1919.

[47] “Central council asks for vote on a general strike”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 22, 1919.

[48] “Strikers will not starve”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 25, 1919.

[49] “Plans complete for the general strike”, Seattle Union Record, Jan. 30, 1919.