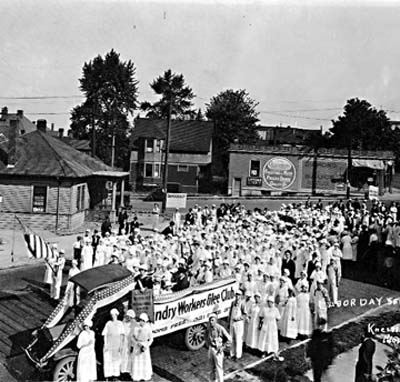

The Seattle Union Record from December 1916 through June 1917 gives us an idea of the struggle undergone by the women workers in the industrial labor force in Seattle. Women who worked in the laundries in Seattle during the World War I period worked long, hard hours and were forced to work faster to receive less pay for their work. As laundry owners increased prices, they refused to pay more and fired women who joined unions or sought out representation. Nevertheless, women organized into unions and when their frustrations rose to a crescendo it culminated in a very successful strike. The struggle of the laundry workers is important because this represented a struggle for a minimum wage for women as well as a maximum workday and most importantly union representation. The Seattle laundry workers are great example of the power of worker solidarity and what occurs in the build up of frustration to obtain a fair wage and union recognition.

Washington State was one of the first four states to enact a minimum wage and an eight- hour workday for women.[1] It is thought that women’s activism and subsequent suffrage enacted in Washington State in 1910 made passage of the minimum wage law possible in August 1915. The eight-hour workday passed once fisheries and canneries were exempted from the law.[2]

During the first part of 1917, the state minimum wage for laundry workers was $9 a week for an eight-hour workday. Before the minimum law went into effect, it was reported that laundries had paid some skilled laundry workers as much as $12 a day[3], whereas others made far less. The laundries then paid less and less until they were paying far below the minimum wage and many workers were receiving the same pay as they had five years previously.[4] In addition to lowering wages, the laundries used several other methods to get around the minimum wage provision.

The laundry plants used a system of “splitting shifts.” This was a practice in which a laundry put the women to “work in the morning, rush them to top speed for a couple of hours, ring a gong and stop their time when the work immediately in sight was disposed of and without previous notice; after an hour or two again putting them to work and in that way compelling them to be present on the job for periods of from ten to twelve hours for pay for from four to eight hours.”[5] This practice of having the women work faster over more hours for less money was upheld in the courts with the decision of Rose Bishop v. Model Laundry Co,[6] in which the judge refused to hear the case.

In 1915, the Laundry Owners Association had attempted to produce legislation making laundry workers exempt from the eight-hour workday law. The owners again tried to fight the legislation in February 1917 actually claiming that the girls employed in the plants wanted a longer working day. The legislative agent of the Washington State Federation of Labor, H.L. Hughes was reported to have dismissed this claim stating, “No laundry girl has ever come to us asking for a longer work day.”[7]

At this time, the laundry workers made very low wages, were on call at all times, and were prevented from joining a union. To avert this latter issue, the Seattle Federation of Women’s Clubs, under the presidency of Viola G. Crahan began organizing “clubs” rather than unions for women laundry workers.[8] Women then had the ability to voice grievances amongst themselves, yet they still had no capacity to argue for higher wages or better working conditions. Mutual Laundry was a union shop and its workers were represented through Laundry Workers Local no. 24.

The Laundry Workers Local met Wednesday evenings at Mutual Laundry. The Seattle Union Record gives us a useful picture of the labor culture in the Laundry Union in Seattle in 1917. Weekly articles relay information about where and when union meetings are held.[9] It informs the reader of whom the elected officers of the union are. Social events for the members, such as dances were fairly commonly occurrences. Newlywed couples were given gifts from the union, for example, an electric reading lamp. There was usually some meal, such as “supper” or a “big feed,” to encourage members to attend meetings; and the number of new members was reported. The man who usually wrote the articles about the union meetings was Carl E. Lunn. Lunn was also the vice-president, declared president February 1917[10] of the local Laundry Union and constantly fought for the rights of the “girls” in the laundries.

The Seattle Union Record reported that at that time, only Mutual Laundry paid the state minimum wage, however Mutual Laundry was cooperatively owned[11] and controlled by organized labor.[12] The Union Record stated that nearly every other laundry in Seattle broke the law in regards to the wage scale. Workers in the laundries were forced to “sign a petition requesting their exemption from the law’s application” according to Joanna Hilt, who was later to become the business agent for the Laundry Workers Union after being blacklisted by the Laundry Owners Association.[13]

Most “girls” received $6 a week through apparent abuse of what was referred to as “the apprenticeship clause.”[14] I am unsure of the details of this clause, however it appears that employers were not required to pay apprentices the state minimum wage, and therefore claimed that their workers were apprentices rather than the skilled labor they truly were.

In 1917, laundries were one of the few places for women to work. The Seattle Union Record dramatically describes the women who work in the laundries as “girls without any family support and many widows with babies to feed and clothe.”[15] According to Richard Berner in his historic accounts of Seattle,[16] women laundry workers in Seattle in December 1916, earned wages averaging $5.87 a week, or anywhere from $3 to $8 a week. Berner points out that such a wage was far lower than the common laborers, typically men, who earned $2.75 to $3.00 a day.

Under a big banner headline, the Seattle Union Record reported in April 1917, that Mutual Laundry was going to increase pay for its employees to $10 a week.[17] This was great news for the laundry workers at Mutual, however the Union Record also states that the wages should really be $12 a week, as a livable wage. Word got around about the wages paid by Mutual and workers in other laundries began ask for similar wages.[18] Near this same time, the laundry workers also began demanding city legislation prohibiting night work and the use of basements for laundry locations.[19] As Richard Berner states, “given the labor shortage and the steady attraction of women into the industrial labor force, the time appeared ripe to deal with the laundry owners.”[20]

In May 1917, the laundry workers union adopted a new slogan: “Activity is the Key to Success.”[21] The union refused to sit idly by waiting for changes to occur. The Union Record stated, “we told you, the Laundry Workers are a live scrapping bunch.”[22] The Laundry Workers Union hired a woman as its business manager, Joanna “Joe” Hilts, who is described as “possessing an extra large supply of fighting energy” so as to engage in a “gigantic struggle” for better working conditions.[23] The women began demanding that all customers solely use laundries that were “union shops.” The Seattle Union Record was vehement that a person’s responsibility was to patronize union-only laundries stating, “union men, please remember…look for the label on your list, the only guarantee that the girls inside, as well as the men, are getting living wages. Be consistent.”[24]

Mutual Laundry was well rewarded for its break from the Laundry Owners Association and its union status. The Seattle Union Record mentioned Mutual Laundry in nearly every article about the Laundry Workers Union and constantly reminded people to only use Mutual Laundry. In addition, the paper encouraged its readers to check the labels with the Laundry drivers to ensure that the women working in the laundries are receiving union wages. Mutual’s business continued to expand, and they proudly reported it had grown to such an extent that they needed two phone services.[25]

The Seattle Union Record made it very clear to its readers that the majority of Laundries were treating their employees quite poorly. The non-union laundries raised prices anywhere from 10-25% without giving the women workers raises. The Union Record encouraged all those who worked in the Laundries to join a union to demand a living wage. The Laundry Owners Association retorted that the women were trying to drive them out of business by insisting on higher wages.[26]

The Laundry Owners’ Association tried to discourage the women from joining the union. They attempted to negotiate on an individual basis with only those who would withdraw from organized labor. If a woman refused to leave the union, she was dismissed from her job. In early June 1917, dismissals became very common.[27]

On Thursday, June 14, 1917, livable wages became an explosive issue, when the laundry workers realized the futility of waiting for the Laundry owners to increase their pay. The Seattle Union Record headline blazed “900 Laundry Workers Out: Girls at Last Revolt at Starvation Wages.”[28] The workers finally went on strike to demand wages that were fair and equal along with union recognition. By Saturday, the Seattle Daily Times reported that while the employers dug their heels in “to the finish,” the laundry workers were gaining the support of the laundry drivers who also threatened to walk off the job, making the strike general.[29]

When the Laundry Owners Club also refused to acknowledge the drivers union, the laundry drivers joined the strike. The Laundry Owners then ran ads in the daily newspapers stating how well paid the drivers were and how they ought to consider themselves lucky that they made wages of $20 a week.[30] This was an attempt to turn public opinion against the laundry strike, and especially deceive the public into believing the women working in the plants made decent wages and therefore had no real grievance.

The Laundry Owners tried many tactics to turn away unions and break the strike. First, they ran ads stating the union was simply trying to aid Mutual Laundry with the strike.[31] The Owners also tried to convince the women who worked in the plants that the union was only trying to get the women’s money through dues. The ploys were unsuccessful and public sympathy remained with the women.

It was reported by the Seattle Union Record that even veterans in the labor movement were surprised at the response from women in the laundry plants. There was not one “desertion from the ranks” since the strike began. On the contrary, the union recruited 600 new members in the first week of the strike and the numbers of striking laundry workers and drivers grew to 1500.[32]

The laundry unions made note of the fact that the Laundry Owners Club was paying thousands of dollars to bring in strikebreakers from out of town, yet were unwilling to spend the money for better wages. Ironically, the Owners then offered women who did not join the union, approximately 15% of the workers, nearly identical wages to what the unions were demanding. The owners simply refused to acknowledge or accept the union[33].

The Union Record pokes fun at the Laundry bosses in its articles as well. It reports how the non-union trucks carry strike guards, stating “there (are) grave fears entertained by the employers that the girls may storm the rapidly moving motor cars and stick the heroic strikebreaker with a hat pin. He might develop blood poison, and-strikebreakers are scarce these days.”[34]

The strike engaged by the laundry workers was very successful. Within hours of the announcement of the strike, two laundries, Enterprise Laundry and Nelson Laundry signed up with the union. Friday morning each laundry put their union employees to work by 8:00 am.[35] The strike was supported by the community. The local Teamsters union gave Laundry workers local 24 over $250. The Ballard Mill Workers gave $2000 to striking workers,[36] and many of the picketers reported passersby stopping to donate money to their cause.[37]

The non-union laundry industry became “crippled” by the strike. Laundries’ business dropped to one third of its former business level and some companies folded. The strike also affected other businesses. The first business to take the brunt of the laundry strike was the hotels in Seattle.[38] They believed they could wait out the strike by switching to paper napkins, then paper tablecloths, but eventually realized that bed linens were a necessity and then urged the Laundry owners to settle the strike. The three union plants, Enterprise and Nelson along with Mutual became overwhelmed with extra business and had to run three shifts to handle the business.[39]

On July 7, 1917, the third week of the strike, the Seattle Union Record reported conferences between the union representatives and representatives of the “laundry owners Association.”[40] There was speculation that the workers may receive their fair wages. This was the first time the owners were willing to negotiate with the union, after having profusely refused up until this point. There were several apparent reasons for the owners to negotiate.

One reason for the talks was a serious rift in the Laundry Owners Club occurred when Proprietor Williams of the Peerless Laundry announced his laundry would be a union laundry. The Laundry Owners Club filed a lawsuit against Williams for “breaking his pledge to the Association.”[41] Public support of the strikers had been growing and the publication of the lawsuit in local newspapers convinced the workers that they would win the strike.

Another reason for the talks was simply financial. The owners were losing too much money paying the “scabs” bonuses in addition to their reduced business income. Another was the cost incurred by employing two men to drive the laundry wagons, the solicitor-driver and the guard. The owners also realized the tremendous business the union laundries were getting at their expense. The decision to negotiate was implemented with the arrival of the president of the International Laundry Workers’ Union, James Brock in Seattle[42].

James Brock provided the experience necessary for dealing with the owners’ association. He patiently organized repeated conferences with owners of the laundries that continually refused to acknowledge the union. The laundries were giving in to some of the demands of the workers, such as higher wages, yet continued to refuse the union.

On July 11, Brock announced a blanket agreement to end the strike. All the laundry establishments except for one were willing to pay union scale of wages to inside workers, engineers and drivers and were being operated simply as union institutions.[43] The employees that had been discharged due to their involvement and activities within the strike were reinstated as part of the blanket agreement.

The strike agreement called for a minimum wage of $9 a week with an eight hour day for inside women apprentices, and a minimum wage of $10 a week with an eight hour day for women journeymen with the number of apprentices limited. The engineers were given a $5 a week raise to $28 to $30 a week for a fifty-one hour workweek. The laundry drivers were given raises based on the amount of work they brought in to be between $18 and $20 a week, still far more than the women workers[44].

While the union considered these pay increases to be great concessions, the greatest feat was that now “the unions have full power to adjust all differences between employees, and with recognition of the union by the employers, only union employees can be employed hereafter.”[45]

The strike and settlement were also boosts to union involvement by women. The first ten days of the strike enlisting over 600 women to the Laundry Workers Union with over 85% of the women laundry workers eventually joining the union.[46]

The strike of the laundry workers in Seattle in 1917 proved the ability of workers who band together to change their employment circumstances. While laws were in place to give workers in the laundries livable wages and working conditions, they were ineffective in helping the women workers in the laundry plants either receive a fair wage along state guidelines or ensure that the employers followed the principles of maximum hour restrictions.

Until the strike, union representation for the workers in the laundry plants was nearly nonexistent. Becoming a part of organized labor, the women’s solidarity gave them the strength and courage to fight back against a very power Owners Association, and to make a difference in their working situation. Of course, women’s pay equality was still unattainable; yet they did gain the ability to make a significant difference. Now, the women had union representation, which meant fairness in pay and closer adherence to the laws. As aptly stated in the Seattle Union Record, “The only way to make labor laws effective is to build effective labor organizations-and then laws will not be needed so much.”[47] In the era before washing machines, laundries were vital and the women working in them deserved fair pay and union representation.

We don’t blame the tailor

When our pants we have to pin;

We do not blame the shoeman

When our shoes grow old and thin;

We do not blame the hatter

When our lids we have to flout;

But we always blame the laundry

When our shirts wear out.[48]

Bibliography

Berner, Richard. Seattle in the 20th Century, 1900-1920 From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Resoration. Seattle: Charles Press, 1991.

O’Connor. Revolution in Seattle. New York: MR Press, 1964.

Seattle Daily Times. June 16 & 17, 1917.

Seattle Union Record. Weekly eds. December 1916-June 1917.

Footnotes

[1] Berner, Richard. Seattle in the 20th Century, 1900-1920. Seattle 1991. p.172

[2] Berner, Richard. p 125-7.

[3] “Minimum Wage and Eight Hour Law Destroyed.” Seattle Union Record. February 10, 1917.

[4] “Checks tell the Real Story.” The Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[5] “Minimum Wage and Eight-Hour Law Destroyed.” The Seattle Union Record. February 10, 1917.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “May Attack Eight-Hour Law.” The Seattle Union Record. February 10, 1917.

[8] Berner, Richard. p 236.

[9] “Laundry Workers Elect New Officers” and many others. Seattle Union Record. December 30, 1916.

[10] “Laundry Workers Want Law Change.” Seattle Union Record. February 10, 1917.

[11] O’Connor, Harvey. Revolution in Seattle. New York. 1964 p 207.

[12] “Laundry Workers Win Big Victory.” Seattle Union Record, July 14, 1917.

[13] Berner, Richard. p 204.

[14] “Mutual Laundry Increases Wage.” Seattle Union Record. April 28, 1917.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Berner, Richard. p 236.

[17] “Mutual Laundry Increases Wage.” Seattle Union Record. April 28, 1917.

[18] “Laundry Workers Get Big Increase.” Seattle Union Record. May 25, 1917.

[19] “Laundry Workers Want Law Change.” Seattle Union Record. April 21, 1917.

[20] Berner, Richard. p236.

[21] “Business Agent for Laundry Workers.” Seattle Union Record. May 19, 1917.

[22] “Laundry Workers Honor Old Officer.” Seattle Union Record. January 20, 1917.

[23] “Business Agent for Laundry Workers.” Seattle Union Record. May 19, 1917.

[24] “Laundry Workers To Hold a Dance.” Seattle Union Record. March 10, 1917.

[25] “Laundry Workers Install Officials.” Seattle Union Record. January 6, 1917.

[26] “Laundry Workers Win Big Victory.” Seattle Union Record, July 14, 1917.

[27] “Checks Tell Real Story.” Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[28] “900 Laundry Workers Out” Seattle Union Record, June 14, 1917.

[29] “Laundry Strike Is Likely to Be General.” Seattle Daily Times. June 16, 1917.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “Checks Tell Real Story.” Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[32] “Checks Tell The Real Story.” Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[33] Ibid

[34] “Stick to It, Girls! We’re All With You.” Seattle Union Record, June 30, 1917.

[35] “Girls at Last Revolt at Starvation Wages.” Seattle Union Record, June16,1917.

[36] “Ballard Mill Workers May Be Unionized.” Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[37] “Laundry Girls May Get a Living Wage.” Seattle Union Record. July 7, 1917.

[38] “Girls At Last Revolt at Starvation Wages.” Seattle Union Record, June 16, 1917.

[39] “Laundry Strike Spreads; Plants Ignore Unions.” Seattle Daily Times. June 17, 1917.

[40] “Laundry Girls May Get a Living Wage.” Seattle Union Record. July 7, 1917.

[41] “Laundry Workers Win Big Victory.” Seattle Union Record, July 14, 1917.

[42] Ibid.

[43]Ibid.

[44]Ibid.

[45] ibid

[46] “Checks Tell The Real Story.” Seattle Union Record. June 23, 1917.

[47] “Minimum Wage and Eight Hour Law Destroyed.” Seattle Union Record. February 10, 1917.

[48] Carl E. Lunn, President of the Laundry Workers Local no. 24, quoting Shakespeare. “Laundry Workers Will Talk Wages.” Seattle Union Record. Dec. 23, 1916.