The Seattle General Strike of 1919 began on February 6th and lasted for six long days. The entire city of Seattle was completely shut down as nearly all of the union workers within the city took part in the strike. The stated goal was to support the Seattle Metal Trades Council, which began its own strike on January 21st in an attempt to gain a wage increase from the federal government. The battle over wages between 45,000 shipyard workers and the United States Shipping Board led to a general strike which shut down one of America’s premier cities on the Pacific Coast and gained the attention of labor and city leaders across the country. The chain reaction that led to the Seattle General Strike began in the shipyards and on the waterfront of Seattle, with shipyard workers fighting for increased wages as they built the ships upon which America’s war effort relied.

In his book, “The Seattle General Strike,” Robert Friedheim attempts to flesh out how the strike materialized in the first place. Yet, Friedheim does not quite get down to the local level within the shipyards of Seattle in the year leading up to the strikes in early 1919. Using his book for background information, but mainly relying on newspaper reports from the Seattle Times and the Seattle Union Record (see Database of 142 digitized articles) , the goal of this paper is to try to understand what was happening on the ground, in the shipyards and local union halls, and what created enough anger and discontent such that waterfront workers felt the need to abandon their jobs and go out on strike.

NEWS ARTICLE DATABASE: Here is a collection of more than 140 digitized news articles from 1918 about shipyard workers and the issues that led up to the 1919 strike that began in the shipywards and then became a General Strike.

World War I brought many changes to the city of Seattle, the most visible being its tremendous growth in population and industry. By 1910, Seattle became a major city with a population of 237,000, a number which grew to over 315,000 people by 1920.[1] This reflected a tremendous rise in industry, with Seattle workers producing $64,475,000 worth of manufactured products in 1914. By 1919, this total skyrocketed to $274,431,000.[2] This quadrupling in production was the direct result of an increase in workforce, and in early twentieth-century Seattle that usually meant an organized workforce.

Seattle was home to fifteen thousand union members in 1915 before the war industries created thousands of new jobs within the city. Towards the end of 1918, that number reached sixty thousand as new workers eagerly joined unions.[3] Union leaders were proud to see Seattle growing into a closed-shop town. Unlike the labor movement in some other cities, labor leaders wanted their unions to take a more active role within both politics and helping to build Seattle’s infrastructure to meet the demand of a growing population. They invested their members’ money into other businesses in the city, including a food store, a labor-owned newspaper, and laundry services for workers. Union’s even went as far as creating their own theater company[4]. The unions also began turning towards political action, organizing their large numbers to support labor-friendly candidates within city and state elections. In Seattle, “usually two or three men on the City Council were not only labor-sponsored, but themselves members in good standing of organized labor,”[5] writes Friedheim. Candidates knew the importance of garnering support from shipyard workers, and candidates such as Mayor Ole Hanson worked hard in attempting to gain the endorsement of the unionized men.[6]

The strength of Seattle’s labor movement resulted in a growing reputation that they often operated outside of the American Federation of Labor’s (AFL) stated operating rules for unions. Many men considered themselves ‘Seattle Union men’ as oppose to just union men, and because of this they were seen as a thorn in the side of the AFL leaders who oversaw the unions. The AFL wanted unions to be organized by crafts, with all laborers that performed similar jobs organized into craft unions. Seattle workers wanted a new form of organization, believing that these smaller craft unions did not yield enough power to face their employers. In Seattle, the idea of industrial unionism was promoted, so that all workers within an industry were represented together, regardless of their individual skills.[7] The AFL’s opposition to industrial unionism prevented Seattle unions from openly adopting the idea. Despite official AFL disapproval, Seattle unions were able to find a loophole during World War I that allowed craft unions to join in an over-arching body to coordinate activities between unions within one industry. In the shipyards, this labor body was the Metal Trades Council, which operated as a quasi-industrial union and brought all of the union representatives together within one council. City wide, labor also came together in the Seattle Central Labor Council (SCLC). Organized in 1905, the SCLC tried to oversee and organize all of the craft unions within the city, allowing labor to act as one single entity if needed. [8] It was through these many levels of organization that Seattle workers attempted to improve their quality of life on the job.

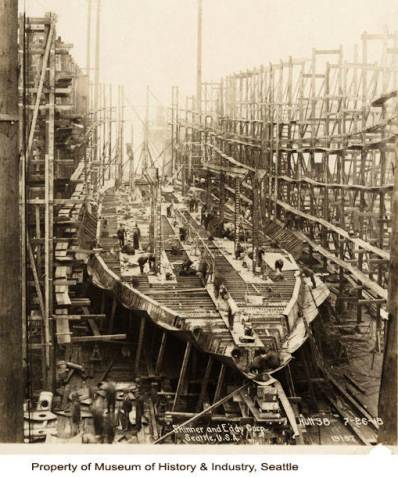

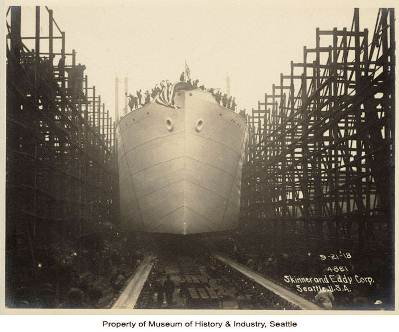

In 1916, the United States Shipping Board was created to “regulate merchant shipping under the American flag and to promote creation of shipyards and the construction of ships.” It regulated the overall function and supervision of shipyard construction and shipbuilding, and delegated the promotion of ship construction to its subsidiary, the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC). The EFC was charged with using government funds, originally $50,000,000 then increased to $2,884,000,000, to purchase ships and to provide the capital to encourage private interests to create shipyards. This led to the opening of new shipyards across the country, with seventeen shipyards operating within Seattle by the end of 1918.[9] The swift creation of so many new yards, which brought huge quantities of workers into Seattle during World War I, prompted many new problems within Seattle which both workers and city officials were forced to deal with.

At the start of 1918, shipyard workers utilized their unions in order to solve one main problem: meeting the needs of the new workers arriving each day to work in the shipyards. The government was asking for more and more ships each week. Being one of the most productive shipyards in the nation also made Seattle one of the most productive cities in terms of recruiting new workers. In January of 1918, the Shipping Board of the United States announced a plan to recruit more than 250,000 new maritime workers for plants throughout the country, and Seattle’s newspapers proudly responded that “We began organizing weeks ago and more than 5,000 men are already enrolled and ready to go to work.”[10] Less than a month later, the Seattle Times bragged that the city upped its quota and expected to recruit an additional 5,000 workers.[11]

In the year 1918, Seattle shipyards ballooned from 16,000 workers[12] to around 30,000 workers by the time of the strike in early 1919. This great increase in manpower allowed the shipyards in Seattle to maintain their record speed and efficiency, with city newspapers proudly boasting of the shipyards’ accomplishment in producing over twenty-six percent of US ships in the first five months of 1918 while employing less than ten percent of the nation’s total shipbuilding workforce of 300,000 people.[13] Despite these totals and the large increase in the shipbuilding workforce, articles still surfaced calling for more men to come work in the shipyards. On August 25th an article called on business and professional men to support their country by finding the time to work within the shipyards. The newspaper proudly claimed that men employed as ministers, high school principals and street car conductors could all be found pulling shifts in the shipyards on top of their regular day jobs.[14]

The large influx of new maritime workers created housing challenges for Seattle. The federal government knew that this was going to be a problem as the Shipping Board decided to set aside $1,200,000 to “provide housing accommodations for shipyard workers at Newport News”[15] shipyards in Virginia. On the same day an editorial appeared in the Seattle Times, asking what would be done to provide houses in Seattle. The editorial contemplated different options, mainly government funding to support government workers, or private funding to build new housing facilities, but wondering if these private facilities would create enough profit to be a viable investment.[16] By February the question was decided, and the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and Commercial Club asked the government for $3,000,000 to aid in the speedy building of homes for waterfront workers. Without houses, they contended that the shipbuilding industry slowed down and that “every delay is a matter of life and death, costing the lives of American boys on the battlefields of Europe.”[17] The federal government responded to these and similar complaints across the nation signing a $50,000,000 housing bill enabling the government to provide housing for shipyard workers across the nation.[18] Yet this bill did not solve the problem, with newspaper articles appearing throughout the rest of 1918 with headlines such as “More Homes badly needed for Workers”[19] in June and “More Rooms Needed to Solve Problems”[20] in early December. The housing problem never seemed to actually go away despite resilient union action and constant newspaper coverage.

Finding housing was only the first problem for the newly arrived shipyard workers. Affording the rent was another issue, as rent profiteering became a serious problem throughout the city in 1918. In early January 1918, the Seattle Central Labor Council adopted resolutions condemning landlords who were using the lack of housing as an excuse to raise rents, denouncing them as “war profiteers” and calling for a full investigation by the United States Shipping Board.[21] The Shipping Board responded that they agreed that rent profiteering was a problem, but were more focused on the housing shortage for war-industry workers throughout the nation.[22] The Metal Trades Council repeated the call for government intervention to help stop the rent profiteering, stating that the “greed of the rent profiteers who are preventing the development of ship building in this city” was akin to treason and must be put to an end. Shipyard workers claimed they possessed evidence proving that rent discrimination was taking place and that they were being charged even more than workers in other industries for similar quarters.[23] It took until October of 1918 for waterfront workers to get some help, as newspapers reported on the creation of the Fair Rentals Commission, which began hearing cases in court and forcing a majority of landlords to lower their rents.[24] While this was a small step, the issue was not completely solved. When combined with an overall cost of living increase and a wage freeze, housing was one of the reasons that shipyard workers demanded a wage increase. Deciding on a course of direct action to increase their earnings, Seattle shipyard workers went on strike in January 1919.

Another problem that the workers on Seattle’s waterfront faced on a daily basis was getting to and from work. In early January of 1918 articles began to appear, first questioning the possibility for street cars and coaches to handle the large numbers of shipyard workers relying on them for transportation each day,[25] and exploring ideas for alternative modes of transportation, such as trains[26] or selling workers motorcycles[27] and cars.[28] Train service seemed the best answer to provide adequate transportation throughout the year with reports of new train lines helping to better transport workers along the waterfront to different shipyards. Yet the problem continued to surface throughout the year, even after the installation of train lines. The federal government did not recognize the transportation problems in Seattle until September of 1918 when a member of the United States Shipping Board visited the city to observe the problem in person. Despite the official visit, the Seattle Union Record reported one month later that workers still struggled to find ways to get to the shipyards.[29]

Upon arriving at work, workers then faced the many inherent dangers of working in a highly productive shipyard. Reports of men being hurt by falling pieces of steel or getting their hands caught in machines and being injured occurred throughout the year.[30] One man drowned in January after being thrown into the water when a slip collapsed within a shipyard.[31] The Seattle Union Record reported that ten members of the local Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders and Helpers union died during the month of May alone.[32] A December 29, 1918 article in the Seattle Times stated that maritime workers asked for the state labor department to take control of overseeing safety within the shipyards. The United States Shipping Board refused the workers’ request to continue to oversee safety practices once the armistice was signed and the war officially ended. In response, the Metal Trades Council passed a resolution calling for someone from the city to enforce the same regulations that were in place during the war. Workers feared the cutbacks in safety procedures that employers could possibly implement once the government ended its shipyard oversight.

Though workplace safety was a concern, job loss and conscription into the military also presented a major concern. America’s shipyard workers were considered to be war-necessary federal employees and were mostly exempted from conscription. For this reason, many people referred to the shipyards as a haven for radicals who refused to support the war. By participating in shipbuilding, leftists could avoid conscription into the military and fighting for a country supporting capitalist ideas, which many of the socialist and radicals opposed. This was the case in Seattle, a city noted for its lack of men able to qualify for Class 1 priority, the class most likely to be drafted.[33] In drives to register men for the draft, Seattle failed to produce enough men to meet the quota and many of those who did register listed shipyard worker as their occupation, helping to exempt them from service.[34] Draft rules were inconsistent and many waterfront workers were drafted despite working in a war-supporting industry. Whether or not a worker was drafted often depended on social and familial connections and whether or not he was able to keep his name off of the draft lists.

The Metal Trades Council was constantly fighting to prevent skilled shipyard mechanics from being conscripted into the military. The Metal Trades Council argued that it took longer to train a mechanic than a soldier, and that through providing needed ships for our country and its allies, a skilled mechanic is at least, if not more, important than a soldier out on the field and should be exempted from the draft under nearly all circumstances.[35] The Metal Trades Council passed multiple resolutions throughout the year calling for more leniency when it came to conscripting skilled shipyard workers, asking professional and business men to be drafted instead.[36]

The primary factor that led waterfront workers to strike for nearly two months in early 1919 was a wage dispute. Robert Friedheim does a great job of describing the injustices shipyard workers felt they were incurring by not receiving a wage increase. The problem was mainly caused by a dispute between the United States government, represented by the Emergency Fleet Corporation, and the shipyard workers and their unions in determining what wages the workers within Seattle should be paid.

The Shipping Labor Adjustment Board, referred to as the Macy Board after its chair, Everit Macy, was set up in 1917 by the EFC to represent the government in all disputes involving wages, hours and working conditions for the duration of the war. Seattle shipyard workers first battled with the Macy Board over wage disputes in late 1917, as workers asked their shipyard management for a wage increase to $6.00 per eight-hour shift for skilled craftsman and an increase in pay for all unskilled labor. Nearly all Seattle shipyard employers refused since the increase would minimize their profits. The Metal Trades Council responded by preparing to call a strike for all its represented workers.[37] The Macy Board granted a 31 cent pay increase, using the wages paid on June 1, 1916 as a base point for the raise. The new wage scale resulted in a basic rate of $5.50 per day for skilled workers in Seattle. This angered the Metal Trades Council, which claimed that by applying the 1916 scale within Seattle shipyards, shipyard management was forced “in many instances to pay union workers twenty-two and half cents an hour less than their fellow unionists were making for comparable work outside the shipyards.”[38] Waterfront workers only stepped down from their confrontations with the EFC, when during their attempt to appeal the Macy Board’s decision, Charles Piez, the director of the EFC, conceded Seattle workers right to negotiate directly with their shipyard employers for higher wages upon the end of the war. As union officials repeatedly stated, workers continued to labor under the current wage conditions because of their strong sense of patriotism and the fact that once the armistice was signed, they intended to invoke their right to negotiate directly with their employers, a tactic which Piez prevented during the war by threatening to withdraw steel allotments from shipyards which produced higher revenues for shipyard owners.[39]

The evidence of these disputes can be found throughout Seattle newspapers in 1918. In January the EFC appointed a University of Washington faculty member to investigate whether the shipyard workers’ claims of an increased cost of living in Seattle were true.[40] The investigation came to the conclusion that the cost of living increased over eight percent within the last five months, a figure disputed by both sides as either too high or much too low.[41] In September, as the Macy Board began delaying its announcement of its new wage scale, shipyard workers protested with a half day strike. The Seattle Times reported that 18,000 workers “laid down their tools at noon yesterday and took a half holiday,” demanding both a 44-hour work week and the expected wage increase..[42] Unrest continued into December when the Seattle Metal Trades Council (?) voted to strike.[43]

Shipyard workers knew that the strike was one of their best tools in attempting to gain a wage increase. Multiple lessons from other industries where strikes resulted in favorable outcomes for workers were readily available to labor unions. The example of shipyard carpenters who struck against their employers for higher wages in early 1918 in Delaware’s shipping yards ended with the US Shipping Board agreeing to a wage increase and a raise in overtime pay. Though the Delaware strike did not increase wages to the extent to which workers wanted, it was still an example in which workers effectively struck and earned higher wages.[44]

Several unions operating under the Metal Trades Council threatened to strike individually throughout the war for varying minor disputes, but the Metal Trades Council as a whole seriously considered striking for an increase in wages until the end of 1918. They already debated the idea of striking in support of Thomas Mooney, a man accused of setting off a bomb in San Francisco in 1916. They actually voted to strike for twenty-four hours in support of Mooney, although no details on whether they followed through with the vote was provided in the Seattle Union Record.[45] With the announcement of the Macy Board’s decision, Seattle shipyard workers became angry and disillusioned with the EFC and its leaders. They appealed the decision and after that step failed, voted in early December to strike against the Macy wage award.[46]

Less than two weeks after WWI’s armistice was signed in November of 1918, the Metal Trades Council voted to strike and made their demands in preparation to negotiate a new wage scale with their employers. Negotiations began on January 16, 1919, but quickly stalled as Charles Piez again stepped in and threatened shipyard owners with the loss of their steel allotment if they negotiated with their employees. In a twist of a fate, the telegram stating this information was sent to the Metal Trades Council, representing the workers, instead of the Metal Trades Association, representing the employers, as Piez intended.[47] Shipyard workers lost the desire to negotiate with the EFC, Charles Piez and the Macy Board. On January 21, 1919, forty-five thousand waterfront workers from Seattle and Tacoma went on strike with the goal of winning the ability to negotiate directly with their employers and receiving a wage increase.

On January 21st, 1919, Seattle and Tacoma shipyard workers left their jobs and went out on strike. In a show of solidarity across industries, other Seattle labor unions joined the shipyard workers and brought the city to a near standstill. In looking through the articles of Seattle’s newspapers throughout 1918, we are to catch a glimpse of the complicated lives of Seattle’s shipyard workers. This helps us to better understand the issues which led to their vote to strike, and subsequently led to the Seattle General Strike of 1919, a turning point for the labor movement in Seattle as well as the rest of the country.

(c) 2011 Patterson Webb

HSTAA 498 Winter 2011

[1] Berner, Richard C. 1991. Seattle 1900-1920: from boomtown, urban turbulence, to restoration. Seattle, Wash: Charles Press. 70

[2] Friedheim, Robert L. 1964. The Seattle general strike. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 24.

[3] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 24.

[4] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 34.

[5] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 35.

[6]“Hanson Making Appeal to Shipyard Workers for clean municipal government in Seattle,” Seattle Times, January 30, 1918

[7] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 32-33.

[8] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 26.

[9] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 56-57.

[10]“Seattle leads US in recruiting for shipyards,” Seattle Times, January 15, 1918

[11]“Army of shipbuilders will be enrolled in nation-wide drive,” Seattle Times, February 10, 1918

[12]“City Offers Good Farming Market,” Seattle Times, January 11, 1918

[13]“Seattle Old-time punch shown in Shipyards,” Seattle Times, June 13, 1918

[14]“Seattle Responds to Shipyard Call,” Seattle Times, August 25, 1918

[15] “US will erect homes for shipyard workers,” Seattle Times, January 1, 1918

[16]“What about Houses?” Seattle Times, January 1, 1918

[17]“Seattle Asks Three Million to build Homes,” Seattle Times, February 15, 1918,

[18]“New Housing Law signed by Wilson Aids Shipbuilding,” Seattle Times, March 2, 1918,

[19]“New Homes Badly Needed for Workers,” Seattle Times, June 9, 1918

[20]“More Rooms needed to solve problems” Seattle Times, December 4, 1918,

[21]“Flay Landlords as Profiteers,” Seattle Times, January 10, 1918,

[22] “Declares War on Profiteers,” Seattle Union Record, February 9, 1918

[23]“Shipbuilding being checked by profiteers,” Seattle Union Record, August 10, 1918

[24]“Landlords told to lower rents,” Seattle Times, October 19, 1918

[25]“Traffic Question Before Citizens,” Seattle Times, January 11, 1918,

[26]“Take Up Plans for Shipyard Trains,” Seattle Times, January 15, 1918,

[27]“Transportation Problem solved,” Seattle Times, March 10, 1918,

[28]“Seattle Shipyards accept deliver of new cars,” Seattle Times, May 12, 1918,

[29]“Shipyard men want better train service,” Seattle Union Record, November 23, 1918

[30]“Three Seattle Shipyard workers are injured,” Seattle Times, June 2, 1918

[31]“One drowned and one injured when slip collapses in shipyard,” Seattle Times, January 17, 1918

[32]“39 Boilermakers in Hospitals,” Seattle Union Record, June 15, 1918. Though the article does not specify how the workers died or if they were work-related deaths, the number seems remarkably high compared to workplace death statistics today.

[33]“Seattle Select Service men of Class 1 Scarce,” Seattle Times, July 28, 1918

[34]“Seattle Fails to Register to Quota,” Seattle Times, August 25, 1918

[35]“Want Productive Workers Exempted,” Seattle Union Record, February 23, 1918

[36]“Metal Trades Have Solution of Labor Need,” Seattle Union Record, August 17, 1918

[37] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 63.

[38] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 65.

[39] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 67.

[40]“Dr. Parker to investigate Cost of Living in Seattle,” Seattle Times, January 23, 1918

[41]“Living Cost goes up 8 ¼% since October,” Seattle Times, February 13, 1918

[42]“Shipyard workers to be back on Job,” Seattle Times, September 22, 1918

[43]“Metal Trades Stand pat on 44-hour work week,” Seattle Union Record, November 16, 1918

[44]“Give Increase to ship workers in Delaware yards,” Seattle Times, February 16, 1918

[45] “Metal Trades vote to Strike on May 1st,” Seattle Union Record, April 27, 1918

[46]“Swain States Macy Strike has carried,” Seattle Union Record, December 14, 1918

[47] Friedheim, Seattle General Strike, 70.