When the Wobblies rolled into town, often coming off the railroad tracks, they came to rally, inspire, and organize their fellow workers into One Big Union, and also to sing. A revolutionary union founded in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was determined to organize workers, advocate for free speech rights, and be all inclusive to workers of any race or gender who wanted to join their ranks. If One Big Union was their goal, singing was one of their most persuasive tactics, and with their music the IWW helped shape labor culture for generations to come.

The story of IWW "songbird" Katie Phar, a 10-year-old Spokane girl, and her correspondence with Wobbly martyr and songwriter, Joe Hill, brings to life the powerful synthesis of music and organizing that the IWW employed in the years before World War I when the radical organization was becoming influential in the Pacific Northwest. Little Katie Phar may have been young when Joe Hill was writing letters to her, but she led her fellow Wobblies in song and kept the music ringing. While Joe Hill is remembered as the infamous martyr who was unjustly executed in 1915, it was his legacy of music that actually made him memorable and helped the IWW organize workers and lead labor actions during the 1910s through early 1930s.

A Labor Culture Strengthen by Music

The labor culture of the IWW was developed through its creation and utilization of songs, poetry, cartoons, jargon, jokes, posters, pamphlets, and newspapers all of which promoted the ideology for the ONE BIG UNION. IWW organizers would circulate their literature and materials in towns, camps, and cities, especially in the West where miners, timber workers, farm workers, and maritime workers suffered harsh working conditions. The organization held free speech fights, such as the Spokane Free Speech Fight in 1909 and the San Diego fight of 1912. At these free speech fights the IWW would make speeches to rally workers, inspire them to start fighting for their rights, and encourage them to join the IWW and strike for better wages and working conditions.

One of the most influential organizing materials was the “Little Red Songbook,” usually sold for only 10 cents. The strikers would sing these songs in the streets and meeting halls, and also in the jails when authorities conducted mass arrests. The music became the heart and driver of the IWW’s labor culture.

IWW songs often were derived from Salvation Army tunes, and for good reason. Several of the free speech battles involved street-corner competitions between IWW soapboxers preaching revolution and Salvation Army proseltizers. City officials typically would ban the IWW assemblies while allowing the religious gatherings, even encouraging the Salvation Army band to drown out the wobbly speakers. The union then turned the tables. As one radical later recalled, the “Wobblies would set some of their most famous songs to the hymn tunes and sometimes sung them on the streets as a kind of retort…most famous of such songs was Joe Hill’s ‘The Preacher and The Slave’ sung to the tune of ‘In the Sweet Bye and Bye.”[1] The IWW strikers would no longer be competing to be heard over the Salvation Army because they would utilize the instrumental music to accompany the lyrics of their songs.

Journalists took note of the singing wobblies. In the American magazine, Ray Stannard Baker wrote, “It was the first strike I ever saw which sang…I shall not soon forget the curious lift, the strange sudden fire of the mingled nationalities at the strike meetings when they broke into the universal language of song…in the soup houses and in the streets.”[2] The songs were being sung anywhere the workers wanted them. The IWW was also proud to be an all-inclusive organization, which explains the “mingled nationalities” Stannard Baker saw. In fact, because the IWW promoted its universalism it could gain more members for its cause and used the songs to rally them—even if English was not their first language they could still learn the songs and express their struggles. Some of the immigrants may not have understood all of the words, but the music brought people together and helped the IWW build solidarity.

Joe Hill: Musician & Martyr

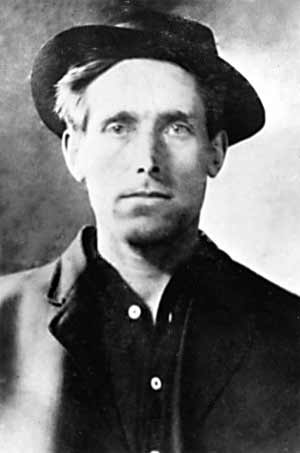

Joe Hill was originally born as Joel Hagglund in Galve, Sweden on October 7, 1879. Both of his parents were musically talented and he learned to play the violin, accordion and guitar after his father built an organ hoping to musically inspire his children. Joel was primarily drawn to the violin, mostly playing it by heart. After his father died, Joel, at 10 years of age, had to start working. By the age 16 he was a rope maker, then a fireman in a wood refining factory. He left Sweden for the United States in 1902, shortly after his mother's death, and eventually changed his name to Joseph Hillstrom. He became popularly known as Joe Hill. In 1910, he joined the San Pedro local branch of the IWW in California. He became one of the top contributors to the IWW “Little Red Songbook,” the author of “Casey Jones-the Union Scab” and many other songs.[3] Other songwriters for the songbook were Richard Brazier, Ralph Chaplin, Laura Payne Emerson, Covington Hall, James Connell, and Charles Ashleigh.[4]

As a songwriter and organizer for the IWW, Joe Hill had recognized the effectiveness of music. In a letter to the editor of Solidarity, written from the Salt Lake County Jail November 29, 1914 he wrote “I am well aware of the fact that there are lots of prominent rebels who argue that satire and songs are out of place in labor organization…”[5] Hill goes on to argue that the accessibility the music helps people understand and feel the IWW message.“A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart.”[6] A song can be learned and repeated, which increases the accessibility and expands the popularity of the message conveyed in the song. He continues “…[if you] put a few cold, common sense facts into a song, and dress them up in a cloak of humor, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial on economic science.”[7] The message of the songs would reach the illiterate and those who did not care to read. Songs were a method to capture various populations of workers and they were memorable, contributing to the legacy of the IWW’s labor culture.

Some of the most intriguing sources for delving into Joe Hill’s relationship with music and his role of using it to enhance the IWW labor culture, are letters written while he was in the Salt Lake County Jail charged with murdering a store owner.[8] He spent almost two years in jail between his arrest in January 1914 and execution on November 19, 1915. The IWW did not become aggressively involved in the case until after after the trial and conviction, as Hill appealed the verdict. The evidence in the trial was notably flimsy. Hillstrom claimed that he was framed because he was a Wobbly. He told the court, “There had to be a ‘goat’ and he ‘a friendless tramp, a Swede, and worst of all, an IWW, had no right to live anyway and therefore duly selected to be the ‘goat’.”[9] Hillstrom ended his address to the court by claiming he had been “tried for being an IWW rather than for murder, saying ‘the cause I stand for means more than human life…much more than mine.’”[10] He knew the prejudice toward the Wobblies played more into the trial than what was fair and was ready to fight for a fair trial. As Hill awaited his fate, the IWW rallied support. “A request for funds was broadcast in Solidarity, wherein Joe Hill was built up by reference to his songs.”[11] IWW members and supporters knew the songs and would listen when they heard the songwriter’s life was on the line as a result of an unfair trial.

Tipperary Song

One of the songs Joe Hill wrote while in jail was sparked through his correspondence with Sam Murray. A letter from December 2, 1914 reads, “No, I have not heard that song about ‘Tipperary’…If you send me that sheet music and give me some of the peculiarities and ridiculous points about the conditions in general on or about the fair ground, I’ll try to do the best I can.”[12] Sam Murray wrote to Hill asking him to write a parody of the song “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” which Hill turned into “It’s a Long Way Down the Soupline.” Murray wanted a song to protest the unemployment and long soup lines that were taking place while the glamorous San Francisco Fair was going on. The next letter to Murray concerning the song reads, “I see you made a big thing out of the Tipperary song…a whole lot more than I ever expected, don’t suppose that it would sell very well outside of Frisco…”[13] but Hill adds that his “Casey Jones” song was a hit in London when he didn’t think the song would be popular outside the United States. Joe Hill had underestimated his songs, thought they would only be successful with the locals, but they were about issues almost every worker experienced. The issues of class and work was universal—they were the battle for better wages and working conditions, to have the right to speak against the employer without being fired, to having respect. In fact, the last letter about the song reads “that Tipperary song is spreading like the smallpox they say. Sec. 69 tells me that there is steady streams of silver from Frisco…unemployed all over the country have adopted it as a marching song in their parades…some changed it to fit the brand of soup dished out.”[14] It is evident from these letters that Joe Hill’s songs spread like wildfire and once they hit the strikers and fellow workers there was no stopping their influence. The power of song thus became more influential than any pamphlet or printed newspaper.

Katie Phar: The Songbird

The letters of Joe Hill also provide insight on the IWW Songbird, Katie Phar. Sources are scarce for her but enough of her story is known to show her role in aiding the labor culture of the IWW. When the IWW held meetings, they were not only for working adults. Members would bring their families to meetings, especially when entertainment was offered. Meetings might include skits, rousing speeches, and, of course, singing. IWW fellow worker Guy Askew recalled that in Seattle the IWW had a junior division for kids and "there was little red Junior IWW cards for them. And children regularly performed at meetings. The shows were full of the “cutest bunch of girl and boy Junior IWWs you could ever hear [singing IWW] songs.”[15]

One of the children was Katie Phar. Calling her the IWW "songbird," Askew remembered her as the leader of the young Wobbly activists. "The little IWW songbird, Katie Phar, brought much free talent to these IWW entertainments and directed them.”[16] Askew's recollections probably date from the early 1920s when the Phar family lived in Seattle. But Katie Phar's involvement with the IWW began earlier in Spokane when her parents, John and Christina Phar, began taking her to meetings and she started learning IWW songs, and learning about Joe Hill.

She was only ten years old when she struck up a correspondence with the imprisoned songwriter. The letters she wrote to Joe Hill are lost and may have been destroyed after his execution when the jail cleared out his cell. However, the letters Joe Hill wrote to Phar have been published and are accessible. Most of the content exhibits their common passion for music.

On October 7, 1914, Joe Hill wrote one of the first letters to Katie Phar. He had painted a rose on the letter using water color, and wrote “roses are now fading away around Spokane that’s why I painted a Rose for you that will keep all winter and I hope your friendship will keep as long as this little Rose.”[17] The letter is signed with “Yours as ever” noting the relationship between the two that is not business based, but purely friendship. It’s very possible that Phar had told him about Spokane and might have been writing to him to give her support while he was waiting on results from the trial. It is very likely that she had read about his trial in Solidarity, and was attracted to the mention of him being the songwriter for many of the songs she invariably sung in the shows.

The next letter was undated (guessed to be January 1915) and it was where the connection through music starts to form. Katie Phar must have talked about taking music lessons in her last letter to him because the letter opens with Hill’s delight to hear her taking lessons and intends to become a musician. He shares the detail about his childhood where he had wished to take music lessons but had to work after his father died, but picked up what little he could. The talent Joe Hill had for music was explained, “You see I’ve got music in my blood and it just comes natural to me to play any kind of instrument.”[18] The common path of music connected Katie Phar and Joe Hill, which strengthened as she told him about learning to play the violin, his favorite instrument, and kept him updated about the IWW activities in Spokane.[19]

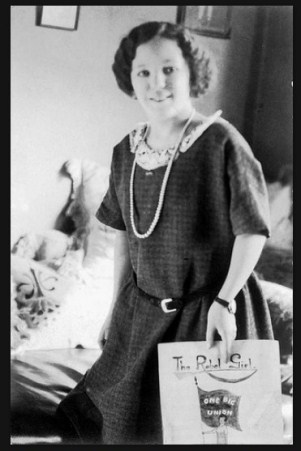

The letter written on May 7, 1915 exhibited further activism through music requested by Joe Hill. He had been sending Phar a few of his compositions and was waiting for her feedback on them. One of the songs he sent was “The Rebel Girl”, which was written about Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Flynn had visited Hill after hearing about the trial. She wrote about the unjust circumstances of the trial and praised Joe Hill for his song writing in Solidarity. Joe Hill recognized the spirit and strength in Flynn as an active organizer and dedicated “The Rebel Girl” to her. In his letter to Katie Phar he described his meeting with Flynn and that Flynn told him her excitement to meet Phar when she comes to Spokane. Hill told Phar, “If you would practice one of the songs you could help her whole lot by singing it at her meeting in Spokane. The Rebel Girl would be best I think because Gurly F. is certainly some Rebel Girl.”[20] Sadly the letter was the last one to Katie Phar before his execution and was incomplete. In some respects, Katie Phar was serving as Joe Hill’s musical voice outside of the jail walls. He couldn’t be in the picket lines, but he sent his music out to musicians, like Katie Phar, who were able to lead the Wobblies in song.

The connection with Joe Hill and Katie Phar also went beyond their support and passion for music, Hill was also a supporter of women in the IWW ranks. In the same letter Hill wrote to the editor of Solidarity on November, 29, 1914, he claimed there was “one thing” necessary to maintain old members and to attract potentially new members, drawing from the tactics used by rebels in his homeland, Sweden. At the time Hill composed his letter, Sweden had succeeded in organizing female workers more successfully than any other nation. On the other hand, the United States, especially on the West Coast, had neglected to organize its female workers. Hill describes the disoriented monster of a union the IWW would be without women, “…a one-legged, freakish animal of a union, and our dances and blowouts are kind of stale and unnatural on account of being too much ‘buck’ affair; they are too much lacking the life and inspiration which the woman alone can produce.”[21] Hill had advocated the value of women in the IWW, that they were central to its success. After all, Katie Phar and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn were two female members who had corresponded with Joe Hill, who he recognized as having positive influence inspiring both new and old members.

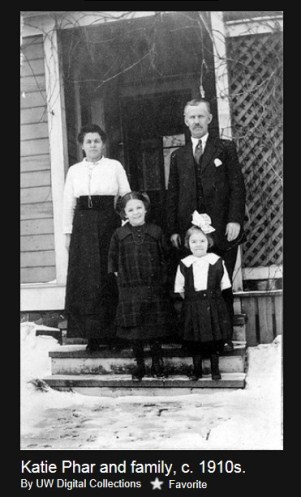

Joe Hill’s letters are among the prime sources for uncovering Katie Phar’s story, but she has also been documented in scattered census records and newspaper articles and the University of Washington Special Collections holds photographs of the young songbird. According to the 1910 Spokane Country census, Phar was 11 years of age and born in Washington state, most likely in the city of Spokane.[22] In 1916, Spokane City Directory listed Katie Phar’s family as John F. Phar, a warehouseman, and her mother Christiania Phar as “house.” The notation of “house” most likely meant she was a homemaker. Katie Phar herself was listed as “Katie M.” and a resident at W2432 Mallon Ave with her parents.[23] John Phar, a member of the IWW, exposed Katie Phar to the organization at a young age. Sometime after that the family moved to Seattle. A 1919 Seattle Times notice placed by Katie offers a reward for the Brownie camera that she lost at the Labor Day parade. According to Guy Askew, Katie was active in the IWW in the early 1920s. In 1930, she was mentioned in the Industrial Worker, in an article describing a meeting at the Seattle-Joint Branch local hall where Arthur Boose gave his speech after “Katie Phar had opened the meeting with a song.”[24] She would have been around the age of 31 at the meeting described in the Industrial Worker. How much longer she stayed with the IWW is not clear. A 1941 Seattle Times entry finds her active in the Emmanuel Methodist Church in Ballard where she was in charge of charitable work helping invalids. She died of unknown causes two years later, at age 44, on June 1, 1943. She was buried near her father in Lake View Cemetery next Volunteer Park in Seattle.[25]

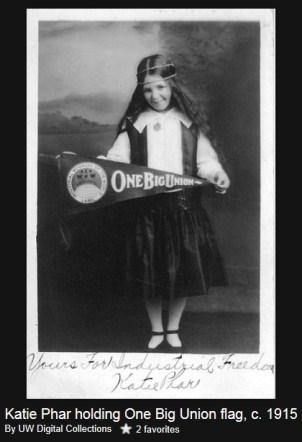

The University of Washington Special Collections holds photographs of Katie Phar in the IWW Photograph Collection. There is also a related IWW pamphlet collection that holds an IWW songbook with “Katie Phar” written on the front cover. While it is unclear whether or not the book belonged to her, it may be the case that someone wrote down her name to remember her, or she just autographed it. The photographs were among the materials gathered from the IWW Seattle Joint Branch when it closed. Any indications of who originally donated the photographs are unknown. The collection of photographs mainly consist of family pictures- particularly one with Phar and her family on their front porch, leading archivists to believe family or close friends in the IWW might have been the donors. All the photos in the collection depict her younger years, with the oldest photo of her in late teens or mid-twenties. The two photographs that embodied the spirit of the IWW and her musical role are the “Katie Phar holding a ONE BIG UNION flag” and a studio photograph of her, with a guitar and a man, who was most likely named Frank. Phar had signed “Yours for Industrial Freedom, Katie Phar” on the photo of her holding a flag when she was ten years old.[26] Miss Phar had celebrity status among the Wobblies, which she effectively earned by leading them in songs for their cause. The photographs captured her charismatic charm and her active role in the IWW music- a musical leader to sing for their trailblazing songwriter, Joe Hill.

Remembering the Songs & Martyr

Before the night of his execution Hillstrom sent two telegrams to Bill Haywood, a prominent IWW leader. In the first telegram he wrote “Goodbye Bill. I will die like a true blue rebel. Doesn’t waste any time in mourning- organize.”[27] His second one concerned his deceased body saying “It is 100 miles from here to Wyoming. Could you arrange to have my body hauled to state line to be buried? Don’t want to be found dead in Utah.”[28] Joe Hill did not want to be left in the state that gave him an unjust trial. The IWW had managed to rally national and international support for Joe Hill after he had been sentenced to be executed, and after his execution, he became an inspiring martyr remembered for his sacrifice and for the legacy of music he left to his fellow workers. The IWW had his body “cremated and small packets of the ashes were sent to each state, except Utah, and to various countries throughout the world.”[29]

The IWWs’ legacy of music would not have existed without its songwriters and songbirds. Anyone who knows the stories of the Wobblies will hear of Joe Hill, not only as a martyr but also as the creator behind some of the most stirring IWW songs. Katie Phar, little remembered for many decades, needs to be acknowledged. Little Katie Phar was not only nicknamed the IWW Songbird, but she was also Joe Hill’s little songbird who believed in his music and helped keep it alive after his death. He looked to her as the youth that would carry on the spirit of the IWW into later generations. Today, workers around the world have the inspiring music to thank for the labor rights they now enjoy. They can use the songs, and the story of the songbird and the martyr, to further the fight for equality and solidarity.

[1] De Caux, Len. 1978. The living spirit of the Wobblies. New York: International Publishers. Pg.51

[2] De Caux, pg. 69

[3] Hill, Joe, and Philip Sheldon Foner. 1965. The letters of Joe Hill. New York: Oak Publications. Pg.7 (Swedish background)-8.

[4] Foner, pg. 8

[5] Hill and Foner, Letter to editor of Solidarity, p.16

[6] Hill and Foner, Letter to editor of Solidarity, p.16

[7] Hill and Foner, Letter to editor of Solidarity, p.16

[8] Hill was accused of murdering a Salt Lake City grocer and one of his sons. The only witness was the younger of the two sons and he only saw two men with red bandanas over their face, attempted to rob the store. One of the robbers was shot in the arm and Joe Hill, not too far from the scene of the crime, came to a doctor to patch his gunshot wound that he claimed to have received in a fight over a lady, who he would not name for privacy sake.

[9] Jensen, Vernon H. 1951. "The Legend of Joe Hill". Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 4 (3): 356-366., pg. 362

[10] Jensen, pg. 362

[11] Jensen, pg. 361

[12] Hill and Foner, pg. 18

[13] Hill and Foner, pg. 26

[14] Hill and Foner, pg. 32

[15] Ellington, Richard. "Fellow worker Guy Askew: reminiscence," inSongs about work: essays in occupational culture for Richard A. Reuss, Richard A Reuss and Archie Green eds., (Bloomington: Folklore Institute, Indiana University, 1993) pg. 312

[16] Ellington, pg.312

[17] Hill and Foner, pg. 15

[18] Hill and Foner, pg. 25

[19] Hill and Foner, pg. 29

[20] Hill and Foner, pg. 33

[21] Hill and Foner, pg. 16

[22] Database: 1910 Federal Census. ONLINE. 2003 and updates 2007. Washington Secretary of State. Transcribed and Proofread by Washington state Genealogical Society.

[23] Spokane City Directory 1916, Washington State Archives-Eastern Region

[24] Classified ad, Seattle Times, September 4, 1919, p.9; "Seattle Helps Illinois Drive." The Industrial Worker, January 11, 1930.

[25] "Autos Needed to Transport Invalids," Seattle Times, May 8, 1941, p.9; Washington State Death Certificate Index 1907-1960; Ellington, pg. 313.

[26] Digital Collections: Industrial Workers of the World Photograph Collection, University of Washington

[27] Jensen, pg. 363

[28] Jensen, pg. 363

[29] Jensen, pg. 364