From early Saturday morning, February 8, 1919, until 4:30am the next day, “radical” and “conservative” union members fought in what the Seattle Star called “one of the bitterest meetings ever held in the Labor temple” at Sixth Avenue and University Street. Seattle had been undergoing America’s first major general strike for just two days, when six unions – including the barbers, teamsters, and theater operators – returned to work without the sanction of the Central Labor Council. These unions were following the lead of the Street Car Men’s Union, Local 587, which had voted to end its strike and restored service that morning.[1] Local 587’s Business Agent, John A. Stevenson, refusing the Council’s order to “for God’s sake put your men back” said simply that “the rank and file believe they have done their duty.”[2] Most early-returning unions were traditionally conservative, well-established, highly skilled craft unions, but the streetcar operators were not.[3] Rather, the Street Car Men’s Union was new and its mostly unskilled members were anxious to hold on to the few benefits they had so recently accrued. Local 587 prioritized actions that would redefine streetcar operators from poorly paid, unskilled workers into the higher rank of well-off “skilled” labor.

The Early Seattle Streetcar System

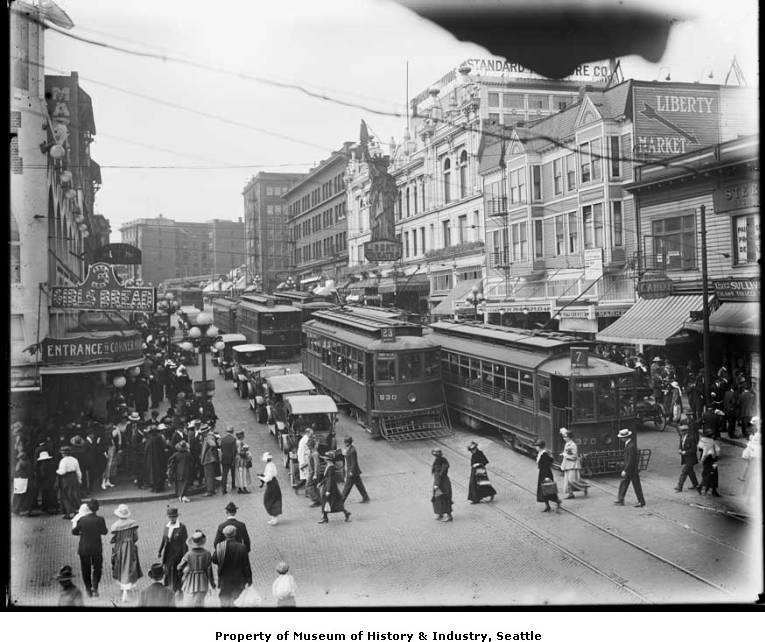

At the turn of the twentieth century, streetcar driving was not a desirable profession in Seattle. Wages were low, turnover was high, and conductors had no protection from the weather. The rhythms of “peak hours” meant that the “ten-hour day” workers were paid for might require up to eight additional hours spent waiting at one of the “barns” where streetcars were kept. Companies hired “spotters” to watch operators and ensure they weren’t pocketing extra fares – or making “any manifestations towards the organization of a union.” Spotters themselves were unsupervised and would reportedly just “lie around the saloons” before delivering “fictitious report[s]” to the companies whereby operators were fired with no redress.[4]

In 1901 Stone & Webster, a Boston-based electric company, bought and consolidated the many small streetcar lines which had been founded in Seattle since 1889. It merged them into the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company (PSTL&P).[5] Almost immediately, in 1903, it cut workers wages. The streetcar operators, who had been unable to organize when split over multiple companies, responded by calling an eight-day strike and forming a union. Ninety-six percent of workers walked out, and the strike was further supported by members of the teamsters union who drove their wagons onto rail lines to stop strikebreaking trains. The new union achieved a two-cent raise. However, shortly afterwards the company allegedly “bought off” the union’s officers who dismantled the organization.[6]

In the years before American entry into the first World War, the PSTL&P faced financial difficulty from rising costs, competition from automobiles, and a state law which prevented fare increases.[7] Between 1913 and 1916 revenue fell by over five hundred thousand dollars.[8] Working conditions had not improved as wages remained low and operators and conductors were still at the mercy of company spotters. One operator described the situation: “you couldn’t even call your soul your own until we got our union.”[9] The situation only declined after the US declared war in 1917. Seattle’s new shipbuilding industry needed workers and experienced streetcar operators left for better paying jobs.[10] In the summer of 1918, about twenty percent of PSTL&P streetcars were idle because of the labor shortage.[11]

Founding the Street Car Men’s Union

The Street Car Men’s Union grew in the 1910s by winning strikes. In 1912 “Mr. Wallace,” a socialist conducting on the Rainier Valley line, one of the last non-PSTL&P streetcar companies, organized his co-workers under an oath of secrecy. All eighty Rainier Valley workers eventually joined, with the holdouts warned they must “either join or get off the job.” With universal membership, the new union revealed itself to the company, immediately striking and affiliating with the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employes (AAS&ERE). The strike was short, and the union was recognized as the Street Car Men’s Union, Local 587.[12] For the next five years, Local 587 remained minor, disconnected from the PSTL&P system where most streetcar workers were employed.

In 1917, Seattle’s streetcar workers watched as many unions including steamboatmen, butchers, newsboys, and builders succeeded in strikes which improved their conditions. They were impressed.[13] In June individual PSTL&P operators started applying to join Local 587, and the Street Car Men’s Union found itself at the center of a citywide streetcar unionization push, represented directly by James Duncan, the secretary of Seattle’s Central Labor Council. The PSTL&P refused to negotiate and fired forty-seven activists. The union called for a strike.[14]

Unexpectedly transformed into a major union, the Street Car Men built group cohesion by scheduling regular mass meetings and began a strike fund to help workers’ families. It protested when the PSTL&P ordered three hundred strikebreakers from the east coast, and when Seattle’s “jitney” drivers, an early taxi service, provided alternative transportation. The company tried to protect its barns from picketers by building barricades and even turned a water tower into a fortress, covering it with sheet metal and installing searchlights.[15] However the union retained the support of the public, and the community began a campaign to boycott strikebreakers’ cars. After sixteen days, James Duncan “got word” that the PSTL&P planned to send a train filled with men “equipped with masks and guns” towards a picket line. Upon hearing this news, University of Washington president Henry Suzzallo, who had been trying to reconcile the strike as part of his role as secretary of the Washington State Council of Defense, demanded the company negotiate to avoid bloodshed as the city was gearing up for war.[16] After a long arbitration session, held up because the word “strikebreakers” in a clause “hurt the dignity of the men from Boston,” the PSTL&P finally conceded to most of the strikers’ demands after Duncan agreed to change the wording to “imported employes.”[17] The company recognized the union – now with 1600 members – and offered a substantial wage increase and the eight-hour day.[18] In a speech to the Central Labor Council in July, Duncan singled out the Street Car Men’s Union as one of 1917’s greatest successes.[19]

In the wake of unionization, Stone & Webster looked to divest from Seattle transportation. The PSTL&P faced heavy criticism from the public which considered their system unreliable, unsafe, and a vector for the spread of “Spanish Flu.”[20] Seattleites considered the company a corrupt force in city politics accused of gaining political favors through under-the-table payments to public officials, including providing free rides and “pearl handled umbrellas” to city council-members.[21] Progressives had long called for the city to take over the street car system and run it as a public utility. And now in wartime, the idea became widely popular. Municipal ownership was favored by the capitalists, the public, and the union, and in what The Seattle Daily Times called “the most important experiment in municipal ownership that this community ever has undertaken,” on December 31st, 1918 the city council voted to purchase the streetcar system for fifteen million dollars.[22] The city promised that it would begin operating the lines by mid-February and began lobbying in Olympia for permission to increase fares.[23]

Who Were the Street Car Men?

Robert Friedheim categorized Seattle labor into three general categories in 1919: skilled, craft-unionist “conservatives” closely aligned with the national American Federation of Labor; industrial-unionist “progressives” represented by Central Labor Council secretary Duncan; and “radicals” who opposed capitalism.[24] The Street Car Men’s Union did not fit easily into these categories. Operators and conductors were not “skilled” in the same sense as craft workers with their years of training. Moreover, despite its foundation by an anti-capitalist socialist Local 587 had generally ignored larger political questions, but by 1919 its officers claimed that “advocacy in certain quarters of a general open shop movement… has made radicals out of many conservatives.”[25]

Unlike craft unions that gained bargaining power because of skill scarcity, street car operators and conductors were readily replaceable since the work required only a week or two of training. Operator Fred Murphy recalled getting a job at 16 because the PSTL&P was so desperate for workers they “grabbed anybody.”[26] However, this “anybody” remained highly selective on grounds other than skill. Dana Frank has problematized framing the Seattle labor movement as a spectrum of conservative to radical by pointing out that racism cut across all these political lines.[27] Streetcar workers in Seattle were overwhelmingly of Anglo-Saxon, Protestant backgrounds and were openly anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant.[28] Only white men were allowed to be hired.[29] When the last Stone & Webster streetcar line in Everett was unionized in 1919 Secretary E.H. Davey reflected the settler-colonialist mindset of the union declaring “thus falls the last of the Mohicans.”[30] And the Street Car Men’s Union was explicitly for men. In 1919, the AAS&ERE countered claims that it discriminated against women, arguing that “operating street cars is not a proper occupation for women” as it was a “menace” to their “morals and health.”[31]

Lead-up to the General Strike

On January 21st 1919, thirty-five thousand Seattle shipyard workers struck, demanding the wage increase that had been promised during the war. Led by the Metal Trades Council, the shipyard workers appealed to the Seattle Central Labor Council and its 110 union affiliates for support.[32] The Central Labor Council then asked each of the city’s unions to seek approval from their members to call for a general strike in solidarity.[33]

The Street Car Men’s Union was not expected to support a general strike since it was still consolidating itself after its 1917 expansion.[34] Over the course of two meetings at Painters Hall on January 30th, Local 587 discussed “the general strike question.”[35] It determined to hold a referendum of all union drivers on February 1st. Conductors anonymously dropped ballots at boxes available at each barn, while a member of the executive committee supervised.[36] Before the vote occurred, an AAS&ERE representative arrived from Vancouver, British Columbia to warn Local 587 that the international would not sanction the move. Nevertheless, striking won by a margin of 676 to 578. This was short of the two thirds majority that would automatically authorize a strike, but sufficient to call another union meeting on the 5th, to “settle the issue” according to Secretary Davey.[37]

The Street Car Men’s Union began to prepare for the strike. The AAS&ERE did not reply to the telegraph wire that Local 587 sent informing them of their decision. Some union members feared that this was an indication they might lose their affiliation and the benefits, such as life insurance, that went with it.[38] The local leadership tried to maintain business as usual. A fundraising ball had been planned for January 31st at Dreamland Pavilion, a dance hall and roller rink often used for labor events, and unionists continued selling tickets out of their streetcars.[39]

Seattle’s government also prepared. Superintendent of Public Utilities, Thomas F. Murphine, promised that municipal public utilities would continue to operate and Mayor Ole Hanson threatened to fire any civil service employee who struck. This was primarily aimed at the City Light Department, because the purchase of PSTL&P’s rail lines was not complete. Mayor Hanson reportedly told James Duncan “I don’t give a damn about the street car company…I need that light.”[40] However, the city did own some small rail lines in north Seattle and Local 587 members feared the Central Labor Council would appease the city by exempting these workers from the strike. They threatened to back out of the strike, insisting that “everybody quit or everybody works,” since any continued streetcar service would “make us hold the sack.”[41]

Just after 8:00pm on February 5th, the Central Labor Council convened to vote on beginning general strike the next day. A majority of the one-hundred eighteen members of the Street Car Men’s Union present indicated that they supported the strike, but that they had to meet again to finalize the decision.[42] At 1:00am, over six hundred members of the Street Car Men’s Union held a final meeting at the Labor Temple Annex and unanimously reaffirmed their decision to join the strike.[43]

Critical decision

The streetcar workers were among the sixty thousand Seattleites who refused to work that Thursday, February 6th.[44] Just eight hours after voting to strike, streetcar operators across the city raised “to the barn” signs on their cars and by 10:00am were off the rails. [45] The street car workers' decision was critical to the launch of the General Strike. Had streetcars continued to run, many businesses might have remained open. And unlike during the 1917 strike, the city’s jitney drivers also joined the strike so the vast majority of the population who did not own their own automobile had no transportation but their own feet.[46]Thus tens of thousands of employees and employers who were not officially on strike, could not get to work and the city ground to a halt. And without the clanging bells and screeching steel on steel wheels, Seattle grew quiet, almost silent. As one striker remembered years later "Nothing moved but the tide."

The Central Labor Council argued that the strike would “teach the workers how to manage business themselves.” The unions worked together to provide food and services to people, pledging for instance to supply the city with milk.[47] Joseph Pass, a journalist from the New York Call Magazine, an organ of the Socialist Party USA, reported that the AAS&ERE representative who was in Seattle to stop Local 587 from striking “after 24 hours… was so affected by the spirit of the hour that he advised the car men to join their striking fellow workers.”[48]

However, many unions joined the general strike not out of solidarity with the shipyard workers or to support the ideal of workers’ self-management, but because they hoped it would benefit their own members.[49] Many streetcar workers were among those who joined the strike out of self-interest. According to streetcar operator Fred Murphy, all the strike meant was that he got to stay home, and it “didn’t make a bit of difference to me.”[50] As the initial rush of the strike wore off, these workers quickly began to doubt that they had anything to gain from continuing.

The first crack in the strike came on Saturday the 8th. Mayor Hanson demanded that the city’s line from Seattle to Ballard be re-opened or all of its workers would be fired. The municipal workers capitulated and according to one recollection, the first car back on the street that morning was operated by a socialist named “Windsor.”[51] Hanson then met with officials of PSTL&P and ordered them to break the strike. Streetcar management, ex-operators, and anyone else the company could find with operating experience were “press[ed] into service” as scabs. As strikebreakers entered the union barns to take the cars, the union members present took no action to stop them or protest. Ten cars were running on PSTL&P lines by that evening, primarily in northern Seattle. The company planned to increase service as it gradually “recruited” more strikebreakers.[52]

Return to Work

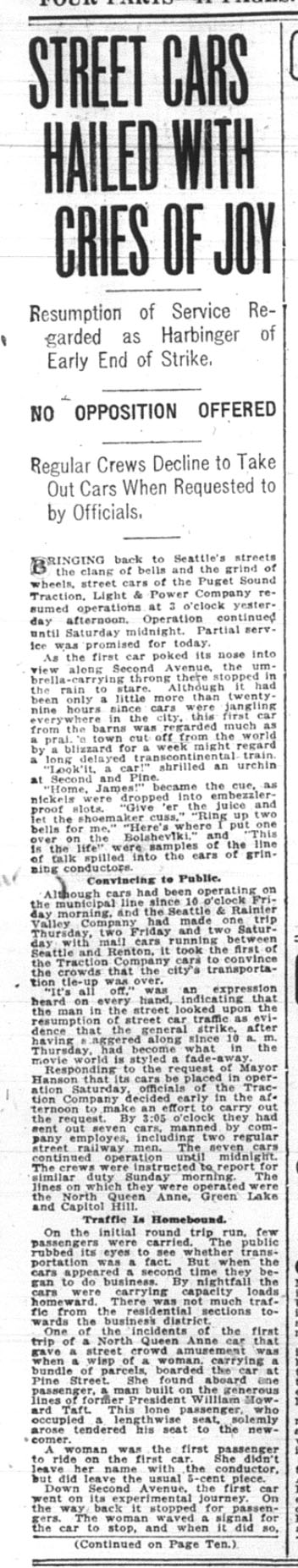

The Street Car Men’s Union faced constant pressure to end the strike. Whether Pass’s story of a representative won over to the cause of the strike is accurate or not, it was clear that the AAS&ERE itself was not pleased. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) considered the strike a hindrance to its east coast organizing, and it pushed its affiliate unions, including the AAS&ERE, to order their locals to end the strike.[53] Additionally, the PSTL&P’s president officially requested the union return to work and promised there would be no discrimination against anyone who did – leaving unsaid the consequences for those who did not.[54] With strikebreaker cars already running through the city, Local 587 voted to comply with the AAS&ERE and that “the purpose of the general sympathetic strike had been served as fully as it could be served at this time.” However, it also resolved that if the Central Labor Council were to call them out on strike again they would obey.[55]

On Sunday morning, the 9th, twelve hundred out of the sixteen hundred PSTL&P employees went back to work, returning ninety-five percent of Seattle’s rail lines to service by that evening. Only on the Lake Burien line did workers act in opposition. Superintendent Murphine alleged that they sabotaged the barn’s eight cars, “their switches molested, air cut off, line switches disconnected, and various parts cut off,” and the line remained inoperable. However the Seattle and Rainier Valley lines had all fifteen of their streetcars back in service, and the Ballard line ran one more than usual. “Emergency men” were brought in to make up for the workers who did not return.[56] Other unions followed the streetcar workers’ lead, with six more returning to work that day.

In meetings throughout the day the Central Labor Council tried to reassert control and get the unions back to the strike, but the pressure from their internationals, the government, and increasingly the public was too strong.[57] The Council recognized that a general strike without full union support was doomed and on Monday the 10th accepted that it was over. It passed a revolution that the strike would end the next day at noon. As a show of solidarity and to “lend dignity to the end of the walkout” it called on all the unions which had already returned to work to strike again until that time. Local 587 did not heed the call, resolving that “we consider a further strike of no additional benefit to organized labor.”[58] Its executive board later defended their refusal “because it was deemed that the action would be of no additional benefit to organized labor, because it was contrary to the instructions of the international, and because it was impossible to call the men together in time.”[59]

The Street Car Men After the Strike

On February 11 the workers of Seattle returned to their jobs.[60] In the wake of the Russian Revolution, wealthy Seattleites framed the strike as an attempted revolution, gloriously put down.[61] Businesses moved to force labor to “clean house,” as Mayor Hanson declared that “Seattle may forgive, but it cannot forget.”[62] In October Seattle employers began a concerted drive to end closed-shop unions. When the general strike began closed-shop unions were the norm in Seattle, by the end of 1920 the closed-shop remained in only nine percent of them.[63] During the campaign, the Street Car Men’s Union ingratiated itself to Seattle business once again and allowed placards supporting this campaign to be placed in over six hundred cars.[64]

When the city finally acquired the PSTL&P’s streetcar system on April 1, 1919 the men who had been first back on the job on February 9th got first choice of where they would work.[65] The Department of City Utilities briefly contemplated reducing streetcar wages, but on May 7th the Street Car Men’s Union threatened that it was prepared to “go on strike again if need be” and the Department quickly conceded, indicating that while most Seattle unions were reeling from the strike, Local 587 was still strong.[66] The city enacted new regulations on jitney drivers which increased income for the city while further empowering the Street Car Men’s Union at the expense of the drivers’ union, which had not returned to work early.[67]

Before the general strike, streetcar driving was seen as poorly compensated, unskilled labor. The work they performed did not change after the strike, but it began to be defined as “skilled.” The benefits in pay and working conditions the Street Car Men’s Union gained after the strike meant that by 1925, Seattle’s streetcar operators had joined the ranks of what Vladimir Lenin referred to as the “labor aristocracy,” the “agents of the bourgeoisie in the labor movement.”[68] They largely considered themselves “middle-class” – earning higher wages than workers in more highly skilled trades and feeling secure in their employment.[69] As the job became more prestigious it also became more restricted. The new municipal ownership fired all non-naturalized employees and implemented a eugenicist hiring policy with mental and physical exams. Operators were suddenly required to be at least five and a half feet tall and half of a cent was deducted from their wages “for each pound he is over or under weight.” It maintained the “unwritten law” that only white men could be hired.[70]

Denzel Cline, a part-time conductor for the streetcar system in the early 1920s, claimed that many streetcar operators “now regard their participation in the General Strike as an ill-advised action.”[71] However, by participating in the strike temporarily and quitting early the Street Car Men’s Union got more publicity for siding with capital than if it had not joined at all. While Seattle’s other unions held off attacks over the next decade, Local 587 prospered.

(c) 2024 Emma Kane-Galbraith

HSTAA 398 Spring 2024

[1] “Tie-Up Broken by Union Men,” The Seattle Star, February 10, 1919, 1.

[2] Central Labor Council of Seattle and Vicinity, Minutes of Meetings of General Strike Committee and its Executive Committee at Seattle, Washington, February 2-16, 1919, 20.

[3] Robert L. Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1964), 37-38.

[4] Denzel Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle: A Sociological Study,” (Master’s thesis, University of Washington, 1926), 22-26.

[5] Paul H. Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” The Journal of Political Economy 29 (June 1, 1926), 455; Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 29. The company was founded as The Seattle Electric Company and it went through multiple name changes before taking on the PSTL&P moniker in 1912 when Seattle City Light was also purchased.

[6] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 31-33.

[7] Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” 456.

[8] Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” 468.

[9] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 36.

[10] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power: Consumer Organizing, Gender, and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1919-1929 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 22.

[11] Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” 456.

[12] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 37-38.

[13] Frank, Purchasing Power, 26.

[14] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 39-43.

[15] “Transportation, Light, Gas, and Fuel Supplies Menaced by Proposal for Big Tieup,” The Seattle Daily Times, January 31, 1919, 2; Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 41.

[16] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 42-43.

[17] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 43.

[18] Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” 456.

[19] Cal Winslow, Radical Seattle: The General Strike of 1919 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020), 89.

[20] “Inefficiency and Profits,” Seattle Union Record, January 9, 1919, 8.

[21] Cline, “The Streetcar Men of Seattle,” 34.

[22] “Seattle’s Gigantic Experiment,” The Seattle Daily Times, January 3, 1919, 6.

[23] “City Decides to Purchase Traction Line,” Seattle Union Record, January 1, 1019, 1; “For Higher Fares,” The Seattle Daily Times, January 28, 1919, 9.

[24] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 37-49.

[25] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 37; “Street Car Men’s Union to Meet Twice Friday,” The Seattle Daily Times, January 30, 1919, 4.

[26] Fred Murphy, interview by Rob Rosenthal, 1977, https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/interviews.shtml.

[27] Frank, Purchasing Power, 20.

[28] Frank, Purchasing Power, 16-17; Jonathan Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State, 1885-1935 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1983), 256.

[29] Cline, “The Steet Car Men of Seattle,” 57.

[30] “Everett Car Men Organize,” Seattle Union Record, January 10, 1919, 7.

[31] “Union Carmen Answer Back: Deny Charges of Covert Discrimination Against Women,” Seattle Union Record, February 15, 1919, 3.

[32] Frank, Purchasing Power, 34-35, 87.

[33] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 80-81.

[34] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 97.

[35] “Several More Unions Decide on Big Strike: Car Men Will Vote Thursday,” Seattle Union Record, January 29, 1919, 4; “Street Car Men’s Union to Meet Twice Friday,” Seattle Union Record, 4.

[36] “Transportation, Light, Gas, and Fuel Supplies Menaced,” The Seattle Daily Times, 1.

[37] “Light and Car Services are Still Uncertain,” The Seattle Star, February 5, 1919, 1; “Street Car Men Vote to Support Strikers,” The Post-Intelligencer, February 2, 1919, 3.

[38] “City to Have Light; Order to Be Enforced,” The Seattle Daily Times, February 4, 1919, 2.

[39] “Street Car Men’s First Annual Ball to be Some Dance,” Seattle Union Record, January 25, 1919, 2; “Long Before ACT Theatre, This Downtown Corner was Dreamland,” The Seattle Times, March 29, 2018.

[40] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 118.

[41] “City Cars to Run, Asserts Murphine,” The Seattle Daily Times, February 4, 1919, 3; “City to Have Light,” The Seattle Daily Times, 2.

[42] Seattle Central Labor Council Meeting Minutes, February 5, 1919, 373.

[43] “Car Employes Call Meeting,” Seattle Union Record, February 5, 1919, 2.; “600 Car Men Vote for Big Strike Again: School Janitors Will Also Go Out with Strikers at 10 o’Clock,” Seattle Union Record, February 6, 1919, 4.

[44] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 3.

[45] “Latest Developments in City’s Strike Situation,” The Seattle Daily Times, February 4, 1919.

[46] “Transportation, Light, Gas, and Fuel Supplies Menaced by Proposal for Big Tieup,” The Seattle Daily Times, January 31, 1919, 2.

[47] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 126-128; “Milk Stations are Announced,” Seattle Union Record, February 6, 1919, 4.

[48] Joseph Pass, “The Seattle Class Rebellion,” Call Magazine, March 2, 1919, quoted in Winslow, Radical Seattle, 198.

[49] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 134.

[50] Fred Murphy, interview.

[51] Fred Murphy, interview.

[52] “Seven Street Cars Operated,” The Post-Intelligencer, February 9, 1919, 9.

[53] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 139-140.

[54] Friedeim, The Seattle General Strike, 144.

[55] “Street Car Men Return to Their Jobs: To Go Out Again When Necessary,” Seattle Union Record, February 10, 1919, 1.

[56] “Union Car Men Return on All Systems Here,” The Seattle Star, February 10, 1919, 2; “No Amateur Did This Job,” The Seattle Star, February 10, 1919, 2.

[57] “Tie-Up Broken by Union Men,” The Seattle Star, 1.

[58] “Tie-Up Broken by Union Men,” The Seattle Star, 1; “Workers Turn Down Order for Walkout to Show Solidarity,” The Post-Intelligencer, February 11, 1919, 1.

[59] “Car Workers Explain Stand: Declare it was Useless to Strike Again When Called Out,” Seattle Union Record, February 13, 1919, 6.

[60] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 5; 146.

[61] “Keep Business as Usual, Urges Mayor Hanson,” The Seattle Daily Times, February 10, 1919, 3.

[62] Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike, 148.

[63] Frank, Purchasing Power, 101.

[64] Frank, Purchasing Power, 97.

[65] Douglas, “The Seattle Municipal Street Railway System,” 455; Fred Murphy, interview.

[66] Richard C. Berner, Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration (Seattle: Charles Press, 1991), 318-319; Seattle Central Labor Council Meeting Minutes, May 7, 1919, 399.

[67] Berner, Seattle 1900-1920, 320.

[68] Vladimir I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline (New York: International Publishers, 1939), 13-14.

[69] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 121.

[70] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 56-57.

[71] Cline, “The Street Car Men of Seattle,” 50.