During the early 1900s, Seattle was experiencing a significant boom in both industry and population. The discovery of gold in Alaska and the arrival of new transcontinental railroads turned Seattle into a center for trade and shipping on the West Coast. [1] One of the many industries that benefited from this growth was the restaurant industry. As the need for low-skilled, low-wage laborers to feed the city’s burgeoning working-class increased, waiting tables became a popular job choice for many of Seattle’s white, working-class women. At the same time, a powerful labor movement was growing in the area and the explosion of organizing extended to the city’s waitresses who unionized in the spring of 1900 becoming the first and longest-running waitresses’ union in the nation. Nineteen years later when over 60,000 members of 110 different unions stunned the country by joining together in a solidarity strike, known as the Seattle General Strike, [2] the waitresses union not only walked out in solidarity but worked with other unions to feed the striking workers. Led by Alice Lord for 40 of its 73 years, the waitresses’ union played a meaningful role in Seattle’s labor movement before, during, and after Seattle’s General Strike of 1919. [3]

Changing housing patterns contributed to the growing demand for restaurants and for waitresses. In earlier generations, workers either lived with families or in boarding houses where meals came with the lodging. By the turn of the century, single workers were finding lodging in kitchenless rooming houses or single-room occupancy hotels requiring them to dine out for all their meals. [5] In 1919, Seattle had an estimated 30,000 single male workers who ate all of their meals in restaurants. [6] This change in focus and increase in clientele caused a boom in the restaurant industry and a massive demand for women to fill serving roles. The expansion and feminzation of the food service industry can be seen in nationwide occupational statistics. In the early 1900s, in the entire United States, only a hundred thousand people worked as waiters, and less than a third of them were women. By 1970, there were more than a million waiters, and 92 percent of them were women. [7]

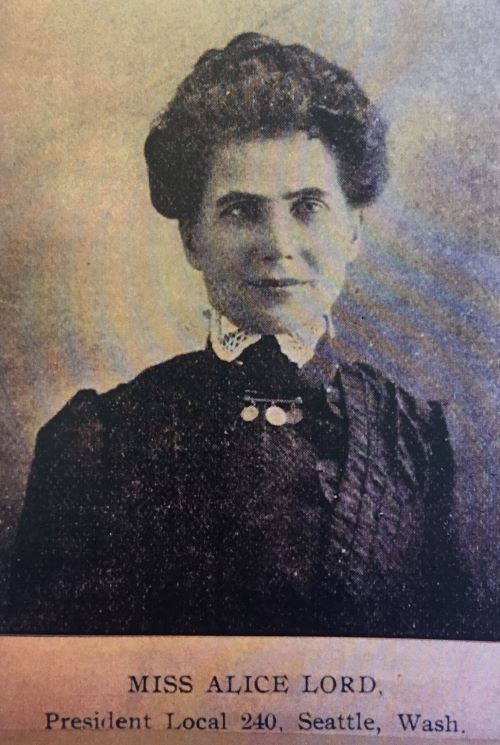

As the restaurant industry boomed, waitressing, despite its inadequate compensation and challenging work, began to increase in popularity as a suitable employment option for women. According to author and historian, Dana Frank, waitressing, clerical work, and sales were the three most common jobs held by working-class Anglo-American women in the early 1900s. [8] By 1920, waitressing was the 14th most popular occupation for women in the nation. [9] Often, the women waiting tables were new to the cities, having moved in from farms or small towns looking to find their place in the modern industrialized nation. Unfortunately, as essential and popular as the work became, the nature of the work, such as long hours and mingling with male diners, led many people to regard waitresses as less than respectable.

In addition to their fight against long hours and low wages, the women of the Local 240, had a strong sense of community and took great care to support its members. A common tradition of trade unions was the opening and running of meeting halls. Union halls were a significant investment and, as a result, often one only afforded by well-established and well-funded unions. Most all-women locals were not able to invest in the building and maintenance of meeting halls. [13] Yet in 1913, the Seattle waitresses’ union opened the country’s first retirement and recreation home for waitresses. [14] In a letter to Mixer and Server in 1911, Lord discussed their struggles in securing funding for the home. Reluctant to accept or request funding from local businesses or “professional men,” Local 240 was working hard to fund the project “entirely of money subscribed by unions and the individual members of unions in Seattle.” In her letter, Lord also explained the importance of providing a home away from home for their workers, many of whom lacked resources or family outside the union. [15]

Another way she fought to care for and support her fellow female waitresses was to keep Local 240 gender-segregated, allowing only women to join throughout its 70-year lifespan. [16] However, despite being only women, the Local 240 supported and received much support from the city’s male unions. In fact, Dana Frank cites support from white, male workers as one of the waitresses’ union’s keys to success. Often, male workers would choose to only dine in restaurants that displayed a union shop card. Union restaurants even advertised their membership in the Seattle Union Record, a union-owned and operated newspaper, as a way to build their business. For example, in one advertisement, the Union Depot Buffet boasted, “Member of Organized Labor for over a quarter of a century.” [17] Additionally, male workers would find ways to support women’s labor actions. Frank tells one story of a waitress strike in Seattle, where some local men took up restaurant tables during the lunch rush only ordering coffee, costing the business sales thereby showing support for the strike. [18] Even when divided by trade and gender, Seattle’s unions had a strong sense of solidarity.

It was likely this sense of solidarity within Seattle’s labor culture that made the Seattle General Strike such a significant and important event. On January 21st, 1919, in a meeting of the Central Labor Council attended by representatives from all of Seattle’s unions, the Metal Trades Council requested a general strike throughout the city as an act of sympathy for the underpaid shipyard workers. There was such a great response to this plea that a General Strike Committee was established and called to meet on February 2nd. [19] At that meeting, the committee agreed to a city-wide general strike that would begin on February 6th at ten in the morning. [20] In a booklet providing a detailed account of the General Strike created by the committee, they stated that “the completeness with which the unions of Seattle voted for the General Strike came as a surprise to many unionists.” They remarked at the willingness of all unions to sacrifice and stand in solidarity with the shipbuilders. [21]

In addition to joining the shipbuilders in their fight for higher wages, the Seattle General Strike Committee agreed that this action should be peaceful and supportive of its workers and the city’s needs. On February 2nd, an Executive Committee was created to organize the strike. The main initiative of this committee was to decide which workers would be exempt from the strike. After hearing many requests from both workers and the city’s mayor, Ole Hanson, over the days leading up to the strike, the committee agreed to offer exemptions for essential services such as city light and water workers, firefighters, electricians, and certain hospital services. [22] Noting Seattle’s workers’ reliance on restaurants, Local 240 put in a request for an exemption to provide what they deemed an essential service. However, the committee denied the request and, instead, decided to run their own kitchens during the strike. The waitresses agreed to participate in the strike and join the culinary unions in plans to feed the strikers. [23]

The waitresses, waiters, and culinary unions would work together on the Provisions Committee to ensure that no one in the city went hungry as a result of the strike. According to the meeting minutes of the General Strike Committee, the Provisions Committee would “take care of the strikers and their families,” and “do such work as found necessary to serve the strikers.” [24] An announcement of the strike from the February 3rd edition of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer notified citizens that “plans are perfected by the workers to feed the strikers and public.” [25] Tasked with what was believed to be the most difficult and challenging job, participating restaurant workers made arrangements to cook in the kitchens offered up by union restaurants and to serve meals at the larger union meeting halls around town. Over the course of the 5-day strike, the Provisions Committee claimed to have fed 30,000 workers each day. [26]

In view of the challenges involved in establishing this massive dining service, it is not surprising that there were problems and complaints. General Strike Committee meeting minutes from day two of the strike show that grievances were brought by transportation workers who claimed that their union cards had not been accepted in union kitchens and dining halls. They claimed the restaurant workers were discriminating against them and refusing service. A motion was made and passed that stated, “all Union cards be recognized by those in charge of kitchens regardless of their affiliations.” Further, to avoid confusion about where service would be available, they voted to create a committee to post signs on all restaurants operated by union cooks, waiters, and waitresses participating in the strike. [27]

Additionally, the committee was under fire for complaints about the quality of food and the efficiency of the service. In the beginning, patrons were to be responsible for providing their own dishes and utensils. However, this did not work, as many diners showed up for meals without sufficient supplies. Also, in the early days of the strike, the committee was still figuring out the logistics of ordering, preparing, and transporting the food. Most strikers complained that they did not get their first meal until late afternoon on the first day of the General Strike. Furthermore, despite serving substantial meals like beef stew, spaghetti, and pot roast, many diners did not feel the meals served were worth the 25-35 cent fee. [28] Seattle’s newspapers picked up on this supposed failure by the Provisions Committee and spread stories of “general discontent” among the workers. [29]

Not only were the strikers affected by limited dining options, but the rest of the city also struggled to cope with the lack of workers available to run the city’s restaurants. On February 8th, Mayor Hanson put out a call for the women of Seattle to do their part and enroll with the League of Women’s Services to work as cooks, waitresses, and assistants and feed the hungry citizens of Seattle. [30] An article in the Seattle Times on February 9th described how restaurants in town whose waitresses and cooks walked out adapted by “preparing easily cooked dishes” and running a “’serve yourself’ establishment during the strike.” City jail kitchens and female volunteers banded together to feed Seattle’s police officers. The news reported that “with all the eating places around town closed or doing but a limited business, the problem of getting something to eat became a serious one for the regular and special officers.” [31] The city’s reliance on the labor of restaurant workers became quite apparent when the majority of them went on strike in 1919.

After five days, the Seattle General Strike ended when union members decided to go back to work despite not having secured higher wages for the shipbuilders. As the city returned to normal, many thought the strike was a loss for the labor movement. The newspapers declared that “the workers were creeping back to work downcast, that they had lost their strike.” However, the General Strike Committee disagreed and wrote that the majority of workers returned to work with a smile and sense of accomplishment for having “done a big job and done it well.” [32] The Seattle General Strike offered the world a powerful example of labor solidarity with thoughtful planning and attention to the care and safety of the citizens of Seattle. The members of Seattle’s unions successfully took on this “big job” and deserved to return to work proud of what they accomplished.

Some of those proud workers returning to work with a smile were the members of Waitresses Union Local 240. Despite working in an undervalued occupation, Seattle’s waitresses joined their union brothers and sisters in solidarity. Ironically, the women spent the strike laboring intensely and serving their fellow workers. It was the opinion of the General Strike Committee that the female unions did more than their fair share of the work. In their account of the strike, they stated, “As a matter of fact all the women’s unions showed a strong feeling of loyalty towards the strike, many of them outlasting the men of the same craft.” This commitment to solidarity and care for fellow workers helped to keep Local 240 strong for many years to come. Indeed, Local 240 maintained its identity and strength until 1973 when it folded into the consolidated union that is today's UNITE HERE! Local 8.

(c) 2019 Jessica Keele

HSTAA 353 Spring 2019

[1] Brief History of Seattle,” Seattle Municipal Archives, accessed May 19, 2019, https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/seattle-facts/brief-history-of-seattle.

[2] “The Seattle General Strike Project,” accessed May 15, 2019, http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/.

[3] Carole L. Davison, "Seattle's 'Restaurant Maids': An Historic Context Document for Waitresses' Union, Local 240, 1900-1940" (MA Thesis, University of Washington, 1998), 60.

[4] Davison, 40-42.

[5] Davison, 40.

[6] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power Consumer Organizing, Gender, and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1919-1929 (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 37.

[7] Dorothy Sue Cobble, Dishing It out: Waitresses and Their Unions in the Twentieth Century, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 2-3.

[8] Frank, 16-17.

[9] Davison, 43.

[10] Davison, 2.

[11] Davison, 61.

[12] Lorraine McConaghy, "True Grit: Alice Lord Demanded Respect for Working Women - and Won," Atavist, September 2, 2016, accessed May 17, 2019, http://features.crosscut.com/true-grit-alice-lord-waitresses-union-seattle-working-womens-rights.

[13] Frank, 76-79.

[14] Davison, 2.

[15] Jere L. Sullivan, ed, Mixer and Server, Volume 20, Hotel and Restaurant Employee’s International Alliance and Bartenders’ International League of America (1911), 37.

[16] Jere L. Sullivan, ed, Mixer and Server, Volume 15, Hotel and Restaurant Employee’s International Alliance and Bartenders’ International League of America (1906), 8.

[17] Seattle Union Record, January 21, 1919, 5.

[18] Frank, 89.

[19] General Strike Committee, The Seattle General Strike: An Account of What Happened in Seattle, and Especially in the Seattle Labor Movement during the General Strike, February 6 to 11, 1919 (Seattle Union Record Pub., 1919), 12-13.

[20] Seattle Union Record, February 3, 1919, 1.

[21] General Strike Committee, 13.

[22] General Strike Committee, 15-26.

[23] Frank, 37.

[24] Central Labor Council of Seattle and Vicinity, Minutes of Meetings of General Strike Committee and its Executive Committee at Seattle, Washington, February 2-16, 1919, Pacific Northwest Historical Documents (PNW01045), 4.

[25] Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 3, 1919, 1.

[26] General Strike Committee, 42-44.

[27] Central Labor Council of Seattle and Vicinity, 6.

[28] General Strike Committee, 44-45.

[29] Seattle Times, February 7, 1919.

[30] Seattle Star, February 8, 1919.

[31] Seattle Times, February 9, 1919.

[32] General Strike Committee, 58-59.