Ole Hanson was Mayor of Seattle in 1919 when the Seattle Central Labor Council led local unions on a general strike that shut down the city for three days. When the strike ended promptly and peacefully, regional and national newspapers gave Mayor Hanson full credit for its conclusion, launching him on a short whirlwind of national celebrity.

During Hanson’s brief fling with fame, his many admirers thought him a heroic champion of Americanism, while his detractors considered him an offensive braggart, even though Hanson’s handling of the strike wasn’t all that impressive one way or the other. What was impressive was the intensity of public opinion about him. Because newspapers and he himself exaggerated his importance in ending the strike, and because at the moment of his prominence the public was looking for a man of his supposed qualities, Ole Hanson became an over-large target for near-fanatic praise from people all over the country.

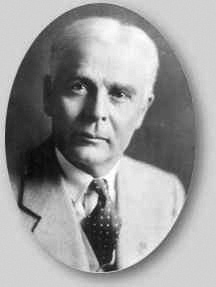

The son of Norwegian immigrants, Hanson moved to Seattle from Wisconsin with his wife and children in 1902, when he was twenty-eight. He set up a reasonably successful real estate business and occasionally dabbled in politics, most notably as a labor-friendly representative in the 1909 State Legislature. With his comfortable middle-of-the-road politics, his impressive oratory, and his ability to distance himself from the squabbling of his opponents, he won the 1918 mayoral election by a wide margin.

A little less than a year into Hanson’s otherwise undistinguished term of office, a wage dispute between the business leaders of Seattle’s declining post-war shipping industry and their employees resulted in a strike by the Metal Trades Union. On February 6th, 1919, the Seattle Central Labor Council, an association of local unions, called a sympathy strike for all Seattle union members, bringing the city to a virtual standstill.

Hanson waited twenty-four hours, then issued a proclamation on the front page of a free copy of the Seattle Star, which said, "...THE TIME HAS COME for every person in Seattle to show his Americanism. Go about your daily duties without fear. We will see to it that you have food, transportation, water, light, gas, and all necessities. The anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs. All persons violating the laws will be dealt with summarily." The following day Hanson sent a telegram to the New York Times, in which he compared the Seattle strike to the recent Bolshevik revolution and claimed that "death would be (the strikers’) portion" if they continued their walkout.

Locally, on that same day, Hanson threatened to subjugate Seattle with martial law if the Central Labor Council didn’t get their strike called off by noon. To give strength to his threat, he draped an enormous American flag over his car and with it led a regiment of soldiers from Fort Lewis into the city. When the noon deadline passed, Hanson gave another ultimatum for eight o’ clock the following morning. Though the Central Labor Council also let the second deadline go by without calling off the strike, individual unions began to break off that afternoon. Before the end of the day the strike was over.

National newspapers were lightening-quick to lay credit for ending the strike at Hanson’s feet. The New York Times trumpeted to the country that their hero was a "champion of order, ...not at all adverse to a little rough and tumble fighting, or any other kind." Of course, the only fighting Hanson had dirtied himself with was with his pen and with his mouth. Still, two days later the Times editorialized, "Many Mayors have talked. Mayor Hanson acted. The revolution failed." Readers of the New York Times were giddily caught up in Hanson fever. One excitedly advised that the US government could not possibly spend its money in a better way than to display Hanson’s proclamation on billboards in every American city and in every language.

Soon other papers across the country followed suite. Rollin Kirby, the cartoonist for the New York World, published a drawing that pictured Mayor Hanson (from the back, since Kirby didn’t know what Hanson looked like) playing poker with a foreign-looking wobbly thug. The drawing was titled "The Winning Hand." It showed Hanson’s cards in front of him, lying in a victorious fan across the table, titled "State, Nation, Law, Order, Grit."

The World was joined in praise for Hanson by the Portland Oregonian, the Salt Lake City Deseret News, the Mobile Register, and the Nebraska State Journal, and practically every other major and minor newspaper across the country. The nation-wide enthusiasm for Hanson was so impassioned it is difficult for a modern reader to stomach.

Local papers seemed at first to be a bit taken aback by the widespread acclaim for Hanson. Then on February 11th, three days after the New York Times first gushed its flood of applause, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer devoted several pages of its front section to reprints from national newspapers. In one article an Oregon legislator motioned to pass a bill to honor the Seattle Mayor. In another article a lady from San Francisco wrote to Hanson, "I don’t know who you are, but I think you have moved the Peace Conference from Paris to Seattle." Suddenly flushed with native pride, the Seattle Times joined the Post-Intelligencer in bragging about how the "East acclaims Mayor of Seattle as Man of the Hour."

But if the Times and P-I were pleasantly baffled by Hanson’s new superstardom, the Seattle Union Record, a prominent daily labor paper, was violently shocked. The Record felt betrayed by the man whom it had commended for his calm support only three days before the strike, but who was now hotly on the attack. Seeking to punish Hanson for his treason, the Record ridiculed his "idiotic, slanderous, vicious and silly mouthings." The paper claimed that Hanson was drowning himself in a flood of words, and that it couldn’t accurately describe him without violating profanity codes and offending its readers.

They described him well enough, however, to provoke Record subscribers to send in a flood of indignant letters criticizing the mayor. One reader wrote the Record to suggest that a petition be circulated to get the government to loan "Holy Ole" to Russia: "The United States is entirely too small for a man of his caliber to be wasting his talents in it."

Mayor Hanson, meanwhile, was thinking that the United States was just about the right size for his talents. Encouraged by the scope and passion of his favorable press, and claiming illness and poverty as his excuses, Hanson resigned from office on August 28th, 1919. He lost no time finishing a very detailed book about his views on the strike titled Americanism versus Bolshevism, and in setting off on a lucrative, yearlong lecture tour. His lectures made him forty thousand dollars, and carried him to the 1920 Republican presidential convention, where his one-note diatribe against Bolshevism began to wear thin. After being ignored at the convention, Hanson retired from politics and fell into obscurity as quickly as he had risen to prominence.

No matter how brightly Ole Hanson had shone from the nations’ newspapers around the week of the strike, when it was over his name went from the headlines to footnotes and stayed there. Subsequent decades have not been kind to Hanson. For the most part, the few historians who have bothered to shake the dust off him and trot him out before the public have done so with an eye towards ridicule and comic relief. Hanson’s strong opinions about Bolshevism seem almost unhinged in modern light. Today, the magnitude and intensity of his fame are, at first glance, baffling, especially when coupled with the abruptness of his departure from the public stage.

But on a closer look, it seems that Ole Hanson couldn’t have helped but be catapulted to fame when he was. He was made a hero because America needed a hero; he was handy and loud and he looked just like one, if you didn’t scrutinize him too closely. Hanson’s stars and planets were lined up just right in 1919: at the exact moment in history that Hanson decided to blow his horn, the press and public were listening for a man just like him.

On the most basic level, newspapers glorified Hanson because he made a good story. Since the strike began, the New York Times had concentrated more on Hanson than on the strike itself. It was easier for the writers and the readers to write and read about one man’s fight against anarchists than to try to dissect the complexities of a labor dispute on the other side of the country.

Hanson was an interesting character for the Times to highlight in their Seattle Strike stories for several reasons. For one thing, he was extremely outspoken and very good for colorful quotes. During the week of the strike he sent several bombastic telegrams to the Times, and they were very careful to print, reprint, and analyze every inflammatory word.

Also, the Times found it ironic that Hanson had once been a proponent of some labor issues. During his term as a representative in the State legislature he had supported an eight-hour day for women and a minimum wage bill. The Times used this record to show that Hanson was well-rounded and reasonable in his approach to labor. According to the Times, Hanson was a man who would normally have been supportive of his city’s unions, but who was driven to oppose them because of the dire nature of their threats and the unjustness of their demands.

Hanson was colorful to papers, too, simply because he was in so many of them. After a while, newspapers ran stories on his popularity with other newspapers. His newsworthiness had become news. This was especially true of local papers who didn’t really catch Hanson fever until they saw how fashionable he was with national papers. If national newspapers had fallen in love with Hanson because he made good copy, local newspapers fell in love with him a few days later because they saw that he was nationally desirable.

So the first key to understanding how Hanson became a celebrated hero is simply that newspapers liked him. But the intensity of the public’s admiration for him went beyond the fact that he was a media darling. The nation was obsessed with him because he satisfied some deeper hunger than the need for people to have something interesting to read about. Ole Hanson was elevated to hero status because he seemed to be the manly leader America needed to pull it out of its post-war mess.

That mess was two-fold. First of all, though American soldiers had just finished proving their masculine mettle abroad, Americans on the home front thought that their society was becoming soft. Many people thought that America’s tough frontier legacy was crumbling in the face of feminism and industrialization. Secondly, Americans were horrified that they were seemingly being invaded and corrupted by Bolshevik foreigners. Ole Hanson, or the picture of Ole Hanson created by the newspapers with his help, fit the bill in both cases. He was a manly, Bolshevik-fighting dynamo.

In the decades before the Seattle strike, the woman’s movement had been steadily gaining steam. More and more women and men had been fighting for gender equality and women’s suffrage. By 1912, nine states, all in the West, allowed women to vote in state and local elections, and women pressed increasingly for national voting rights. In 1920, the year after the strike, the women’s movement of the progressive era would culminate in the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment.

In the same decades that Americans were seeing the rise of the "New Woman," they were also watching the last death-throes of the vanishing western frontier. After 1910 more Americans lived in cities than lived on farms. Businessmen and urban jungles had replaced cowboys and open ranges. American men and boys could no longer go west to prove their manhood, as Theodore Roosevelt had done at the end of the previous century.

While, for the most part, Americans supported women’s suffrage and the rise of business and industry, many of them felt that the nation had acquired those things by giving up some kind of national masculine spark. They longed to restore a sense of manhood to American culture, as sociologist Michael Kimmel wrote in Manhood in America. "Something had happened to American Society that had led to a loss of cultural vitality, of national virility. That spirit had to be retrieved and revived for a new century."

Americans hungered for a leader who could be a symbol of American manhood and help them restore it. For years, of course, that symbol had been the original Rough Rider, Theodore Roosevelt, who before his presidency had been a boxer, rancher, big game hunter, and war hero. But Roosevelt had died only days before the Seattle strike. Just when Americans were mourning the ex-president’s passing and feeling the hole that he had left in American culture, Ole Hanson miraculously burst on the scene. Here was a politician who could fill the big man’s shoes as a symbol of American masculinity.

Hanson himself worked hard to project an aura of heroic manhood. In his lectures and autobiographical articles, Hanson stressed his frontier origins. Like other hardy pioneers before him, he had made the long trek west on foot behind a covered wagon. He had pitched his tent on the hills above the "child-city" of Seattle and, just as other cowboy legends had become leaders in their cowboy towns, vowed to one day become mayor.

Newspapers around the country emphasized that in Hanson the country had found a man. Calling him a "fighter," and a "man of force," the New York Times recalled that, during his westward journey, he had stopped in Butte to help squash a labor battle "just from the sheer love of excitement." He was "strong" and "brave," a man of "courage and that essential, unyielding Americanism," with a "backbone that would serve as a girder in a railroad bridge." He had broken the strike without any help from anybody else, smashed the insurrection through his singular force of will and law.

Citizens from all over sent Hanson telegrams thanking him for his manly stand. From Wyoming: "Gratified to know we have one true American mayor." From Indiana: "Congratulations. You are the only one to avert impending calamity." From Maryland: "I thank God we have men of your caliber to meet such conditions with the force of your high office." From Chicago: "Seattle is to be congratulated that she has a real two-fisted man for a mayor."

Hanson was not only the man to restore America’s masculinity in the era of feminism and urbanization; he was also the man to purge America of that dangerous pestilence of Bolshevism. Towards the end of the War, after the success of Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution, Americans transferred their hatred of Kaiser’s Germany to Communist Russia. They were afraid that Communist ideas would spread to the United States through radical labor leaders and left-leaning foreigners. Their fears crystallized into a national craze at the onset of leftist strikes, riots, and bomb threats across the country. Many Americans adopted an intense, nativist fear of anything that had a hint of Red.

Luckily, Ole Hanson was there to assure them that their fears were valid and that he could save them from Bolshevik dangers. Actually, Hanson wasn’t new to Red baiting. Anti-Bolshevism, which for him meant bashing the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), had been the one issue he had had any strength of feeling on when he campaigned for mayor. In a pre-election speech he condemned the I.W.W. and what it represented to him. "It is against me and against you and against our government," he told his audience. "They should be driven out from our city, from our state, from our country."

After the newspapers made it appear that Hanson had crushed the Seattle strike, the nation turned to him as their savior from Bolshevism. According to the Times, he was "living proof that Americanism, that respect for law, is not dead." Moving his soapbox from Seattle to the national stage, in lectures and articles Hanson preached about what "Americanism" meant: rule of law, democracy, increased production, a strong national government, universal military training, education, morality, and the deportation of "unassimilated aliens."

His preaching was met with roaring applause. The San Francisco Chamber of Commerce wired to thank him for his defense of American rights and the Constitution against "the assaults of anarchism and the enemies of our American government." From Milwaukee a man wrote to wish that every city had a Seattle mayor, "and then the Bolshevik question would be settled for good." The entire town of Union Grove, Wisconsin, wanted him to continue to "hit hard and let that scrofulous crew understand that we live in the good old United States and not in Bolsheveki-ruled Russia."

To some, Hanson’s qualities of manliness and anti-Bolshevism were so striking they thought he should be leading the country. They were coming up, after all, on an election year. The Times agreed with New York Republican leader William Barnes that Hanson should be nominated for president, citing his courage, high principles, and contempt for political consequences. The Times compared him favorably to the ailing President Wilson, and fondly recalled that Hanson had met Wilson once, when he was visiting the White House to raise money to buy Seattle’s power plant. Hanson had become so excited about his cause he had actually taken off his coat in the presence of the president. Surely a mayor with that much gumption was the man to whom the country’s torch should be passed.

But by the time the Republicans had their national convention the following year, they had lost their crush on Hanson, nominating instead the more palatable Warren G. Harding. Certainly Hanson had been interesting and flashy in print, but so were a lot of fads. In the next decade Americans would also think marathon dancing and flagpole sitting were interesting and flashy. Certainly Hanson had been touted as a symbol of manhood, but before long manhood would be measured on a scale of money and market savvy rather than on Hanson’s frontier machismo. And certainly Hanson was unparalleled in the passion of his fight against Bolshevism. But after the post-war disquiet settled, Bolshevism didn’t seem so threatening, and Hanson’s rhetoric sounded a little too fanatic.

Less than a year after he was hailed for breaking the Seattle strike, Ole Hanson was looked on as more of a crank than a hero. His fifteen minutes were long gone.

©1999 Trevor Williams

SOURCES:

Really, there are no secondary sources if one is studying the public perception of Ole Hanson. There are, however, two substantial treatments that would belong in the secondary source category if one were studying Hanson himself. The first is heavily anti-Ole; perhaps more than is necessary. The second is more favorable, and is, in fact, partly a reaction to the first.

Robert L. Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1964)

Terje I. Leiren, "Ole and the Reds: the ‘Americanism’ of Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson" Norwegian American Studies 1985 30:75-95

PRIMARY SOURCESOle Hanson, Americanism Versus Bolshevism (New York: Doubleday, Page, and Company, 1920)

Hanson began this 300-page book immediately after the strike. In fact, one of the reasons he resigned his office was to give him the time to finish it. Even while he was still mayor, critics said that he neglected his duties in order to work on it. The first third of it contains a brief autobiography and a necessarily one-sided account of the Seattle General Strike. The rest is a history of "Bolshevism" in Europe and in the United States and a prescription for stopping its spread. It shows the intensity of his opinions and hints at his skill as an orator.

Delores Huteson Hughes, "The Impractical Dreamer," an unpublished manuscript by Hanson’s granddaughter, in Manuscripts and Archives, University of Washington Libraries

Evidently a school paper, this is written in a worshipful tone. It gives valuable information about Hanson’s doings after his popularity faded. He squandered his lecture tour money, then made a small fortune in Mexican oil and founded the Southern California city of San Clemente.

Friedheim Collection, Manuscripts and Archives, University of Washington Libraries

Compiled by Friedheim while he was working on his book, this collection deals with the Seattle General Strike as a whole. The most interesting item devoted to Hanson is a copy of the transcript of People vs. Lloyd, a trial in which Hanson was an expert witness. Hanson retells his role in the strike and talks about his lecture tour. He is verbally thrashed by Clarence Darrow.

Washington State Newspapers

Hanson dominated just about all of the local newspapers right after the strike. The general readership newspapers were concerned with congratulating him and cataloguing his rise to prominence. Typical are the Post-Intelligencer and the Times.

Post-Intelligencer

On February 10th, 1919 the P-I credited Hanson for ending the strike. On the 11th they ran several pages of excerpts of praise for Hanson from other newspapers, both local and national. On the 15th they printed a speech Hanson gave to the Chamber of Commerce. On April 29th they described a failed bomb attempt on Hanson’s office, and August 28th they covered his resignation.

Seattle Daily Times

Unlike the Post Intelligencer, the Times covered Hanson’s 1918 election quite thoroughly. On March 2, 1918 they printed a story titled "Ole Hanson’s Record," which listed his platform, accomplishments, and several letters of support. On February 10th, 1919 they joined the Ole parade with an enormous front-page portrait and biography. Like other newspapers, they praised him for the next few days.

Union Record

A labor daily, this paper is fun to read because it seems to be the single member of the "We Hate Ole" club. Actually, the Union Record wrote favorably about Hanson on February 3rd, just before the strike. On the 6th they seemed baffled by his antagonism, and by the 11th they admitted that they couldn’t print the words they would have liked to use for him. In every issue from the 11th to the 20th they found new bad things to say about him. On the 14th and 15th they printed insulting cartoons. On August 29th, when Hanson resigned, they devoted more front-page space to him than they had to the General strike on its first day: "Hanson Quits…City Hall Rid of Freak."

National Newspapers

As the February 11th P-I article chronicled, newspapers from all over the country had good things to say about Hanson right after the strike. The most complete was the New York Times, which actually beat Washington papers to the punch in Hanson praise.

New York Times

On February 8th, the New York Times did a story on the Seattle General Strike, but seemed most enamored of Mayor Hanson. The proclamation Hanson sent them by telegram, printed on the 9th, probably had a lot to do with their featuring him, and with his subsequent popularity. On the 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 18th, and 21st they quoted readers and politicians with Hanson fever. On April 29th they covered the bomb; on August 28th they covered his resignation; on September 18th they interviewed him; on July 22, 1920 they mentioned his testimony at the Lloyd trial, and then they never mentioned him again.