Dr. Linda Vorvick

Since 2004 Dr. Linda Vorvick has worked for MEDEX Northwest, largely under the title of Director of Academic Affairs. Now moving on to another full-time job for the University of Washington, Linda reflects back on her 12 years with MEDEX and her accomplishments collaborating with a team of faculty and staff.

MEDEX: When we first met, you told us about your multi-year approach to transforming the classroom at MEDEX. Can you give us a progress report at the time of your departure from MEDEX?

Linda: Transforming the classroom meant changing both the physical space and the approach to teaching. And the great thing about this transformation was that the whole didactic team across all of our sites was on board with transformation. We’ve done a lot of experimenting over the last several years, and now we’re narrowing in on things that seem to be most effective for our students and our program.

So the first bits of transformation concerned what actually happens when you try something new. We wanted to get more interactive teaching—that was the bottom line. We had some upper campus professors come in and talk to us about how people learn. We looked at some of the literature on interactive teaching. Problem-based learning and team-based learning were really popular as methods of active teaching. So we decided we were going to start experimenting with different pieces of interactive teaching at all four sites.

We started doing team-based learning in technical skills. You do a test with the students using a multiple choice test before the class starts, then you do a test as a group during class, then you teach the class after you’ve done these testing exams. It helps focus the students on what’s important. It gets them to play with the information before they start hearing it. It leads to higher levels of interactivity with the information. So we did it. We put it together enthusiastically. And we hated it! And the students hated it! And that’s really typical of starting something new.

First change that, in the short-term, turns out a disaster may actually yield long-term positive change.

The main reason people hated this new approach was that we didn’t have much experience with it. It was new to us, so we were uncomfortable with that style of teaching. The second reason was that it was uncomfortable for the students. They had been socialized to sit and listen to lectures and extract the information they needed. They didn’t like having to do it differently because it discombobulated their ability to decide how to study. And so to have different styles when they were so used to one style didn’t work very well. That was the short-term impact of trying interactive teaching.

The long-term impact of this approach to teaching was that, individually, people started seeing other ways to implement similar kinds of interactive teaching, rather than rote team-based learning. Part of it was that the structure of pure team-based learning was too confining. And so what’s happened since then is that all of our teachers think about how to make their teaching sessions interactive.

We still call them lectures, but we’re trying to lecture less than half the time and otherwise do cases, or do group work, or do visual work, or use video or use some simulation, or use some hands-on practice. If you look through our curriculum over the last several years, you’ll find more case work, more hands-on practice, and more multi-media than we’ve ever had in the curriculum. People are experimenting and finding the style that works well for them, and they’re using that style to teach.

Our students are really liking it—they really like the interactive teaching better. It’s easier when it starts at the beginning of a cohort of students so that it’s mixed in all along, and they don’t get acculturated to just lecture, they get acculturated to different kinds of learning. So the interactive teaching is something that we all talk about internally and we all strive to continue to do. That was one piece of that long-term transition: getting away from straight lecture and getting to interactive kinds of teaching.

MEDEX: Of course you were instrumental in the transformation of the physical classroom as well. It’s apparent that a lot of thought went into designing the classroom to support interactive learning.

Linda: Our prior classroom had chairs with fold-up writing desks. And because nobody had computers when these chairs were developed, the desks were slightly sloped. So a computer wouldn’t stay stable on it. Your coffee wouldn’t stay stable on it. The class had a sign like you’d see at construction sites, which said how many days they had without an accident, without a coffee spill because of these sloped desks. And it was usually zero or one, because pretty much every day somebody’s coffee went flying. These desks were terrible.

The only good thing about them was that they were so small you could create groups really fast. But everybody was so close to each other that people got into a lot of interpersonal conflict from lack of personal space and lack of control. There was no place to store anything. There was no desk you could call your own.

These are adults who had productive careers before coming to that small classroom with these inadequate desks and chairs. They only fit one size, so it was like one size fits none. Really, it was dehumanizing, and it did not provide an environment for learning. The lighting was bad, and the lights were set up for the presentation to be on a side of the room that we actually didn’t use anymore. That meant that when you turned the lights down to present a PowerPoint, you pretty much had to turn the lights off in the entire room. The only good thing about the classroom was that it had a door to the break room and people could escape to get coffee and food and things like that.

Every year the students would ask if they could paint it. Can we bring in tables? Can we bring in different chairs? And the answer, unfortunately, given the bureaucracy of the university, was always “No, we can’t do those things.” So we started looking for space.

There is no space in the UW Health Sciences Building—it’s already jammed packed, crammed full. The fact that we even had a classroom in Seattle that was dedicated to us in the T-wing was pretty remarkable. But over the years we started noticing that the wet lab behind us that held 50 people started getting used less and less.

The Seattle didactic faculty started a data gathering project where we would peek in the window of the wet lab every day and record when we saw somebody in it. UW classroom services who booked the rooms thought that the lab was full all the time because courses had it booked, but nobody actually went to the lab. The courses were basically hogging space in case they needed it rather than using the space. So after a couple years of observing, it was determined that the space went empty all of winter and spring quarter, was used some in fall quarter, but only intermittently. We had to be ready to move to take that space.

There was a simultaneous political process as well. MEDEX Program Director Ruth Ballweg and I went to see then Vice Dean for Student Affairs Tom Norris to say that our classroom was inadequate. It was not useful for teaching, and that our creditors (ARC-PA) were going to tell us that our classroom was inadequate and that we needed to do something. Dr. Norris supported us by getting the head of the T-Wing building assignments to come to a meeting with him and us, and basically charged him with finding us space. We had follow up meetings with him in which he told us that there was no space.

In the process of getting the data together about the underused wet lab, we had a meeting with the head of the building to say that, in fact, there is a space that was open, and could we have that space?

We went to the School of Medicine to make sure they weren’t really using the space anymore, and determined that they weren’t. Then we had a meeting with the building people and we requested a list of everybody who they think actually uses the space. After a couple meetings, we got that list from them, and started contacting the people for those courses to ask if they actually used the space anymore or was it a year-over-year automatic re-reservation that was obsolete.

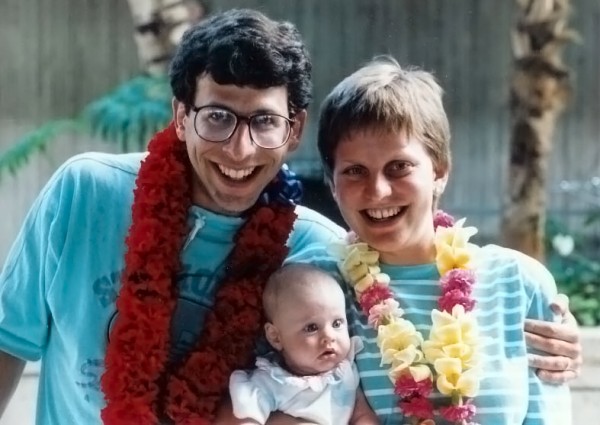

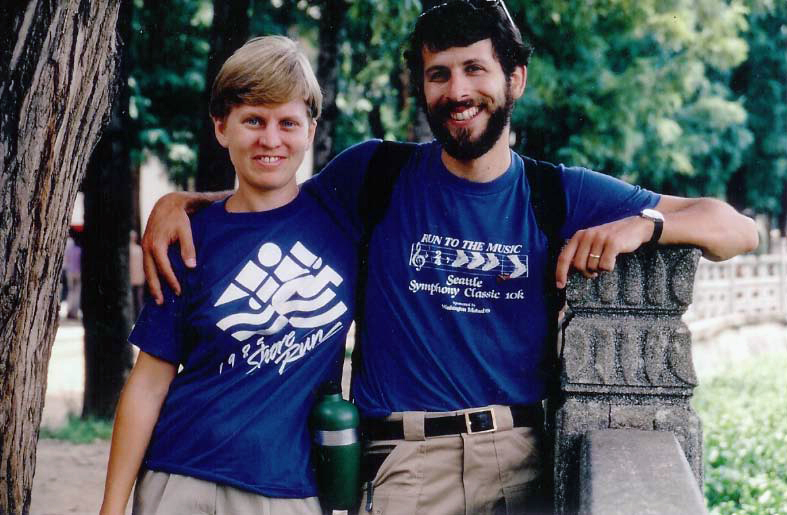

Linda Vorvick and Steve Brown in China while on a 11-month travel break after her residency in 1985.

And in the middle of that process we talked to a few people in the School of Dentistry, which had been using the space as a wet lab to do anatomy of the mouth and head and neck. Just that year they had changed to doing all of that anatomy by slides. They were not doing it in a wet lab anymore, and were no longer using the space.

We just started using the space because it was twice as big, even though it was built as a wet lab. So even though it was an awkward classroom, we would use it a lot. Just as we were about to get a meeting to discuss the available space, the person who schedules room bookings sent us an email inquiring as to how much are we using this wet lab? We knew that was the time to pounce. If we didn’t get our claim in right now then somebody else was going to gobble up that space.

We called a meeting with the head of the building to say that we wanted this space, and that we wanted to remodel it. What do we have to do to get it? And the reply was, you have to turn your old classroom back into a wet lab.

This made me do my signature happy dance. Because if that was the main obstacle for us to get the space, that’s something money can fix. And the fact is that even with money, we can’t make space in T-Wing. There is no space in T-wing. So if the only way to get space was to spend a little extra money to get a classroom that was twice as big, that was suitable for our students, that wasn’t cramped, and that was ready for interactive teaching—of course, we’ll make the old classroom into a wet lab! Which we did as part of the remodel.

Once we got the commitment to the space, we got together a team of people to start planning. Amee Naidu, Donna Lewin, Audrey LaRue and I were the main people on that, and John Stevens for the technology. The reason the new classroom works as well as it does it that we put the time in to do the details. We went and looked at lighting all over T-wing and we picked the lighting ourselves. We went down to South Lake Union and looked at the panels and technology, and made our panel in the front of the classroom like the kind they have at South Lake Union.

We went to the video and audio vendors and looked at their smart boards and determined that they weren’t plug and play. It was not worth investing the money in Smart Boards. Instead, we invested in a distribution system that allows us to hook seven computers up to the projector and choose between the inputs. We looked at whiteboards and glass boards, and picked glass boards that would be easy to clean and wouldn’t deteriorate like the whiteboards often do if you write on them with the wrong kind of pen. We picked colors that were soothing. We picked a floor that was going to look nice. We picked chairs that were comfortable. There’s felt board on the walls to keep the sound down, and wall washer lights on the side, which means that even when you turn all the lights off in the classroom the room still feels bright because light’s coming in from the sides, not just overhead.

There were a lot of details that all of us did by consensus. We did this by going and looking and picking and watching the architects.

We wanted two fridges and four microwaves because we’ve got almost 50 people all trying to do lunch in the break room at the same time. The architects put the fridges right next to each other in the back of the break room, and the microwaves around the corner from each other in the back so they could have this large open break room with all this stuff in the back. It was like, hey, 50 people can’t fit in the back of that room! That was never going to work. People are going to be tripping over each other. You need to make two stations—one at the back, and one at the front, each with a refrigerator and two microwaves and the sink in the middle. So we were even down to correcting the architect’s design and making sure they had things in the right places. We had to stay on top of every single detail, just like any other kind of remodel project.

MEDEX: I think people love it.

Linda: They do. After three years of winter quarters now, I think the students’ mood is better in winter quarter than it has been in the past because they’ve got space that’s reasonable. Each of their desks can be individually moved up or down for height. There’s a little pocket for them to store their stuff so they have a little bit of private space. Their chairs are all adjustable. And the desks are shaped such that you can turn people to each other and work in groups really easy and really fast. Then we’ve got seven glass boards around the room, and the students are constantly using those to study with each other informally during breaks. You walk in any day and there’s stuff on the boards that they’ve been using to study. So it’s effective not only during class time but the students find it a really great place to study by themselves too, apart from class time.

MEDEX: I wonder if you have any other accomplishments from your time at MEDEX that you’d like to talk about?

Linda: Well, I think there are a lot of things that have happened while I’ve been at MEDEX that are certainly not only mine, but the efforts of a whole team that came together to make things happen. One of them was our concerted effort, starting about five or six years ago, to increase our PANCE scores. This years’ scores are substantially above 90%, I think they’re running 93% or 94%—somewhere around there. Our low was 78% first-time pass rate. And when you have a pass rate like that, there are multiple things happening, and you have to do multiple things to improve. And people have stepped up across the entire program—from admissions to didactic to clinical to study skills to remediation—in order to bring those scores up.

The part that I particularly focused on was the remediation, though Amee Naidu and Tim Quigley do most of that now. To make a change like that sustainable, you not only have to change your admissions, which we did by being more specific about our prerequisites, but you have to have a lot more robust remediation policies. In the effort to bring everybody up, I focused on making sure that our didactic teaching was aimed at the right topics, and that we were spending the right amount of time on the right topics. There are sort of two ways to fix a problem like this: you remediate the people that are struggling the most, and then the second prong of fixing a problem like this is to bring the average scores up.

And so we went back and did a huge project mostly for the Adult Medicine course under Amee Naidu and Vanessa Bester, with others helping as well. We literally cut and pasted every topic that we teach across an entire year at MEDEX, and reorganized it based on the PANCE blueprint. We did this to see what topics we weren’t teaching that we should be teaching, what topics we were teaching too much, or what was too little. We went back and looked at everything with several ideas in mind. One, it was on the PANCE and we needed to teach it. Two, it was something that Primary Care people need to know how to do. So that’s more about skills, like taking a history, doing a physical.

So we went back and reallocated time in the curriculum. All of the course chairs were wonderful about this, and slashed their objectives that had gotten too large or that weren’t as relevant. They added back courses that were more relevant. The course chairs have really stepped up and look at this every year now at their summer retreats. Each course now is really paying attention to what are we teaching and does it meet those criteria. They’re also looking beyond their own course. Are we duplicating other’s work? Are we teaching too much of something because both of us are teaching it when only one of us needs to?

We’ve improved the didactic curriculum by focusing on those aspects that are really important about the didactic curriculum that prepare people for their clinical year. Probably the biggest piece of work that has actually lead to the sustained improvement of the PANCE scores has been putting together a sustainable model for didactic learning in the clinical year. That’s involved through several iterations, and we’re on a new iteration right now.

Our faculty are very focused. They understand that this is the part that sustains over over the long haul. Now we have national average or above scores for our PACKRAT 1 test at the end of the didactic year. So that says while we can still improve, we’re teaching the basics of what we need to teach for the first year. The key is to continue to improve on our second-year performance and sustain that progress. People continue to learn didactically during their clinical year, and not just the clinical skills they need. There is curriculum now in the clinical year aimed specifically at didactics. So there are clinical year modules right now that Susan Symington and DJ Smith put together that are the latest iteration. That’s going to make the biggest difference.

The didactic curriculum is always a work in progress, but it’s in good hands with the course chairs. All the course chairs understand why we are with the interactivity and that the content is continuously being reevaluated to make sure it’s focused in the right places. The interactivity is really about learning. Can we get people to learn at a higher level of thinking about being able to problem solve rather than just memorize? So that’s keeping the didactic curriculum fresh.

MEDEX: Can we talk a little bit about when you first came to MEDEX, and the circumstances of your arriving here?

Linda: It took me six years to get a job at MEDEX. Dr. Dick Layton introduced me to Ruth Ballweg in 1988, when I left clinical practice because I was allergic to the latex. I was sick enough with my asthma and the latex allergy that I just had to get away from the latex in clinic in order to get my asthma under control. And at that time, there was really no alternative to latex in clinic. Latex allergies were relatively new, people were just starting to understand them. And so it seemed pretty dramatic to just leave clinical practice entirely. But because I was a little bit ahead of peoples’ understanding of latex allergy, that was really my only choice.

So Dick Layton introduced me to Ruth Ballweg and said Linda will make a really great faculty member. And Ruth said yeah, why don’t you come do a lecture for us? I started doing the GYN breast pathology and GYN pathology lectures for Henry Stoll starting in the fall of 1998, and I did that for six years.

I worked as an administrator in a medical group, and then I was laid off from that job. Then I worked at a health plan, and I was laid off from that job. Then I worked for a drug company, but I was laid off from that job. And on the side, I did a second job, which was editing medical information for patients on the web, and I still do that as a second job. By the time I told Henry I’d been laid off for the third time, he called me about six weeks later and said we could use some help with maternal child health course. Would I like to come work for MEDEX? That was in January of 2004. And at the time I was very seriously considering opening a bakery and getting out of medicine entirely. So I said, “Yeah, sure, I’ll come, but very part time, like one and half, two days a week, and I’ll help you out a little. I’m not looking for an education career. I’m going to open a bakery.” So over the next six months, I started doing more and more teaching and thinking less and less about the bakery. In July of 2004, Ruth offered me a job as a faculty member, and I’ve been a faculty member ever since.

Director of Academic Affairs is main role that I played at MEDEX for a very long time. I did serve as the interim Section Head and Director for about a year and a half, and now Terry Scott is the Section Head.

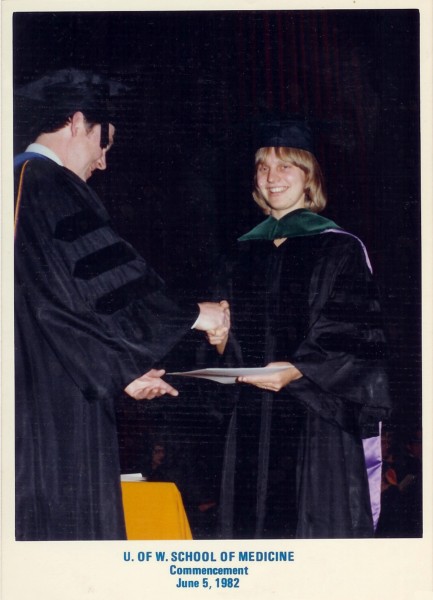

MEDEX: Let me ask you a few questions about your time here at UW as a medical student. I know there’s a portrait of you in front of Hogness auditorium. What year was it, your graduation year?

Linda: I was what we all considered E78s. We entered in 1978 and I graduated in 1982. Then I did my residency here under Dick Layton at Providence with an underserved urban population, which is now the Swedish Cherry Hill Residency here in Seattle And so I finished family medicine residency in 1985.

MEDEX: You had a very close relationship with Dr. Layton.

Linda: Yes, I did, and that developed over time. He was my residency director and you always get to know your residency director pretty well. There were only 12 residents and 4 faculty members when I started, and we added an extra one, so we ended up with 14 residents and 4 faculty members. So everybody knew everybody super well. Later, after I went into practice, we sold our practice to Providence Hospital, and Dick Layton was the Medical Director of the medical group that I was in. And I was one of the administrators in that group. And so I worked with him again at the end of his career when he was a Medical Director of Medalia and I was one of the administrators for Medalia.

Linda: Yes, I did, and that developed over time. He was my residency director and you always get to know your residency director pretty well. There were only 12 residents and 4 faculty members when I started, and we added an extra one, so we ended up with 14 residents and 4 faculty members. So everybody knew everybody super well. Later, after I went into practice, we sold our practice to Providence Hospital, and Dick Layton was the Medical Director of the medical group that I was in. And I was one of the administrators in that group. And so I worked with him again at the end of his career when he was a Medical Director of Medalia and I was one of the administrators for Medalia.

MEDEX: Let’s talk about next steps. Tells us where you’ll be going, and what the job will entail.

Linda: I’m really thrilled to be staying inside the University and inside the Department of Family Medicine, and connected to MEDEX. I want to continue doing the lectures, teaching sessions I’ve done in the past for A&P, pathology and for maternal child health. I have about one to two lectures a quarter that I have done for years and years. And I’m hoping to be able to continue to do those. I plan to keep teaching once I get settled in clinical practice. I plan to take PA students and hopefully even inter-professional opportunities at the clinic.

The clinic I’m joining is a UW neighborhood clinic, and it’s at Smokey Point in Arlington, which is just north of Marysville. It’s a clinic that has providers who’ve been through several different practice arrangements. The University recently just acquired this clinic. That’s a little different for the University as they usually build the clinics from the ground up.

I’ll be starting March 1 with two months of orientation, and then May 1 I will be starting as the Medical Director in that clinic and seeing patients there full time. I can go back to clinic now for basically two reasons. First, there’s no latex in clinics anymore. There’s enough people allergic to latex that it’s not in the medical system at all, except for very specialized areas. And the second reason is that when MEDEX joined the family medicine department, I had the opportunity to go back to clinical practice by supervising residents. So I’ve been supervising residents for the last three years, and I feel like I sound like our PA applicants. It’s been fun to see patients with the residents, but I’m ready to see them on my own. I’m ready to do more.

I’m ready to go back to clinical practice. It wasn’t my choice to leave clinical practice. I sometimes say I’ve been making lemonade out of lemons for many years, and now I have the chance to go back and actually do what I was originally trained to do, which is to see patients, manage a clinic, think about population health, think about the populations that are in Arlington and how we can serve them better. Think about all the different aspects of what it means to have a healthy community. I’m very community-focused for my family medicine approach, and so while I’ll enjoy taking care of the individual patients one at a time, what I hope is that, over the years that I am at Smokey Point, we start to think of our medical practice as a piece of the fabric of the community, improving community health and community well-being.

I can’t tell until we’re up there, but I’m hoping it involves using quite a few of the University’s resources, which will be new for that community. I’ve done a lot of work in interprofessional education, so I would love to have nursing students, social work students, public health students, PA students, dental students and medical students to come help us figure out how to have an impact in the community there. I see it as a very large group project eventually. There’s a lot of steps to break down there, there’s a lot of work to be done, and that’s not something that’s going to happen in a year or two. But I’m planning on being there for 10 years or so.

The bottom-line idea is that people feel best about their practice when they feel there’s some social capital that they’re getting from doing the work. And to have an effective practice that doesn’t burn out providers, the social capital needs to not just be individual, it needs to be collective. For me, that collective social capital is about what’s happening in the community. We’re going to have an impact in the community and we’re going to think about what’s really going to make a difference in the community. That will get people out of their own heads and working as a team. Then they’ll have more fun at clinic and it’ll just trickle down to be a fun place to work. It will be a place that is successful and people will come because they know that we care. Which is the bottom line, the reason people go to get health care is because they want to be cared for.

I’m just thankful to everyone I have worked with. I’ve had so many opportunities. I’ve had so many people I can bounce ideas off of. I’ve had so much that I’ve learned about teaching and life in these last 12 years at MEDEX, that it’s not going to leave me where I go next. And I’m not planning on disappearing from MEDEX. I want to stay connected. Steve and I have an endowed fund for emergency funds for our students and we want to keep supporting that endowment, along with Gino and Ruth. I’m changing focus but I’m not leaving MEDEX behind.

MEDEX: One more thing: I wanted to speak to your avocation. Could you tell us a little bit more about your talents and your desires to be involved in baking?

Linda: Okay, well my signature baking is chocolate chip cookies. I would bake two or three recipes a week all the time we had kids growing up. I can’t do that anymore because there’s nobody to eat them, and we certainly don’t need to eat them. But I’ve taught both my kids to be able to make chocolate chip cookies without a recipe. I love baking. My current find is from a recent trip. I found these measuring cups that are marked for the amount of grams of flour and sugar and water etc., because in Europe, all of the recipes are done by weight.

And so some enterprising person realized that you could get close enough to the weight if you took a measuring cup and then just marked it by the weights rather than the volume. Now I am the proud owner of a large and a small measuring cup that’s marked by weight so that I can measure flour and then sugar and then water for my baking recipes. Because it turns out baking is a lot like chemistry. You have to be pretty accurate as proportions matter. You can’t be a little too much of this ,or little too much of that, because then it doesn’t turn out right. So yes, I’m a big baker, I’m big baseball fan, and I am a girls’ softball umpire. Those are the things I do to keep myself busy when I’m not thinking about medicine and teaching.