Sepideh Makouei (pronounced SEP-ee-dah Ma-KOW-ee) is in her second year of the MEDEX Northwest physician assistant training program. There are over 60 providers working at the UW Medicine Neighborhood Northgate Clinic in Seattle where she’s fulfilling her 4-month family practice preceptorship. Among them are attending residents as well as physicians, PAs and nurse practitioners with many years of experience.

“I like it,” Sepideh tells us. “I like an academic environment anyway. My parents are teachers, so I understand the difficulties—the goods and bads—in a teaching environment. I get so many different views on treating just one single problem, because of the views of various practitioners and their different approaches.”

For generations in her native Iran, Sepideh’s family had worked in medicine—her uncles, aunts and cousins. “But not my father. I think he’s the only person in the family that’s not in medicine.” Her mother worked as a school principal.

Now, Sepideh is resuming the family tradition.

“As a kid, I wanted this,” she says. “Everybody on my father’s side of the family was in medicine with different specialties, so it wasn’t unfamiliar to me. I knew how it works.”

In August of 2017 Sepideh will graduate from MEDEX and, upon passing the national certification exam, add the credential PA-C to her name. Still, it’s been a long path to become a medical practitioner, with lots of obstacles along the way.

“The era when I grew up, it was a hard time. There was a war during my childhood.”

Sepideh is referring to the war between Iran and Iraq from 1980 to 1988. “It took eight years of our lives,” she says.

To set the context, the Iranian Revolution came to power in 1979 with the overthrow of the Pahlavi Dynasty and the Shah, long supported by the United States. The government was replaced by the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeini, supported by various leftists, Islamist organizations and student groups.

“It was a hard time,” she explains. “The Revolution happened, and the country was under sanctions from many European countries and the United States. There were different ways in which Iranians were working to influence the direction of the country.”

Among them were Communists, championing a new direction in response to oppression. Others were known as Lefties, operating in the interests of individual rights. The most radical position was held by the Islamists.

Sepideh’s parents were nationalists. “They believed in everything that makes a country flourish and be a best nation,” she says. They had supported Mohammad Mosaddegh, a famous Iranian political leader of nationalist principles. As the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953, Mosaddegh wanted oil profits to go to the people. He nationalized the Iranian petroleum industry, which had been under control of the English.

As nationalists in a time of revolution, Sepideh’s parents were not seen as good citizens of Iran. Islamic fundamentalism clashed with the modern era, and ordinary citizens felt the impacts. Sepideh’s mother was prosecuted in court for her views.

“She didn’t believe in covering herself with a hijab,” Sepideh tells us. “She was a principal at a school in my home town Makou, and didn’t believe in forcing people to cover themselves with a headscarf after the revolution.”

At that time this was considered a serious offense, one that held consequences for any woman who dared veer from the prescribed path. “If you didn’t cover yourself, they would cut your face, throw acid on your face or ankles if they were showing, or you had on nail polish.”

Sepideh was raised knowing that she could voice her opinions. “We grew up knowing that you have to talk. You have to. If you don’t accept something, you have to speak out. So, I was against all that.”

Sepideh was raised knowing that she could voice her opinions. “We grew up knowing that you have to talk. You have to. If you don’t accept something, you have to speak out. So, I was against all that.”

Because she was seen as being in opposition to the government, Sepideh herself was jailed for a time, as was her brother. The problems started after she got into the University of Tabriz where her major was biology, with a minor in botany and two years of research on genetics.

“At the university, I had a hard time proving to them that I was actually a person who could educate herself and become something,” she says. “Because of my opposition to the government, I was given a hard time by religious groups at the university.”

In her last semester, Sepideh was informed that she was ineligible for graduation because her behavior was unacceptable. The university dropped her research, and informed her that she would have to be reeducated before being eligible to graduate.

“I had to take like two or three classes in religion, on how to behave in Islam as a Muslim woman. So, that was the last straw. I graduated and left.”

That was in 1993, but Sepideh didn’t come directly to the US. The first 10 years after leaving Iran took her to several different regions: Southeast Asia, Europe and South America. “For those 10 years I basically had a sense that nowhere was safe,” she tells us. “You protect yourself. Even today, I’m a little bit reserved in that respect, and not really that open.”

By 2002 Sepideh settled in the United States. She had two small children, essentially functioning as a single mom because their father had moved back to Iran. “He wanted to experience the new era of the country,” she says.

Remaining in the States with her children and elderly parents, Sepideh couldn’t find a job. “I hadn’t worked in 10 years, so I decided to study something.” The Lake Washington Medical Assistant Program was attractive because it offered a part-time study option. “With two small kids I needed to be flexible with my time.”

Reflecting back on her university education, her early decision not to go into medicine was deliberate. “By the time I got to the age when I could choose, the war had just finished,” Sepideh says. “I was under so much stress. I didn’t want to see another person in pain. So, I decided not to go into medicine at that time. Seeing so many dead people, and people with injuries all around us, it was just heartbreaking.”

But now, years later and in a new country, entering the profession of her father’s family seemed a good choice. She graduated from the MA program. To start, she worked at a nursing facility and as a nursing aid in Redmond until settling into two part-time jobs—one in private practice, and one in Urgent Care at Evergreen Hospital. “By the time I started seeing patients, I was like, ‘Okay, this is what I want to do, this is what I would like to do.’ Really, it gave me lots of joy to talk to people, to try to understand their pain or what their problem was medically. So I started looking around to see what is going on in medicine, and if there was something more I could do.”

Sepideh looked into PA programs. “One of the people who actually saw me for my migraines was a PA. I became very curious about PAs and applied to the MEDEX program in 2008.”

She was granted an admissions interview but, unfortunately, got sick that year. “I couldn’t make it, and then it took me some time to recover. I had complications after my surgeries and treatments.” It took Sepideh another seven years to return to the program when she reapplied in 2014.

At the time of her 2014 MEDEX interview, Sepideh had another option in place just in case PA school fell through. She was in her first quarter of nursing school at North Seattle College. “Then I got the MEDEX phone call and I thought, ‘This is what I really want to do’. You go to the interview thinking this is what you want, but you don’t know if you’re going to get in.”

Sepideh took an attitude of whatever happens is going to happen. “It wasn’t really the only option for me because I had nursing school in the background. I wasn’t scared, but I knew it would be the last time that I would apply. Honestly, it was like this: if I don’t get it, I don’t get it, I won’t pursue it anymore.”

“But I’m so happy that I got in,” she tells us.

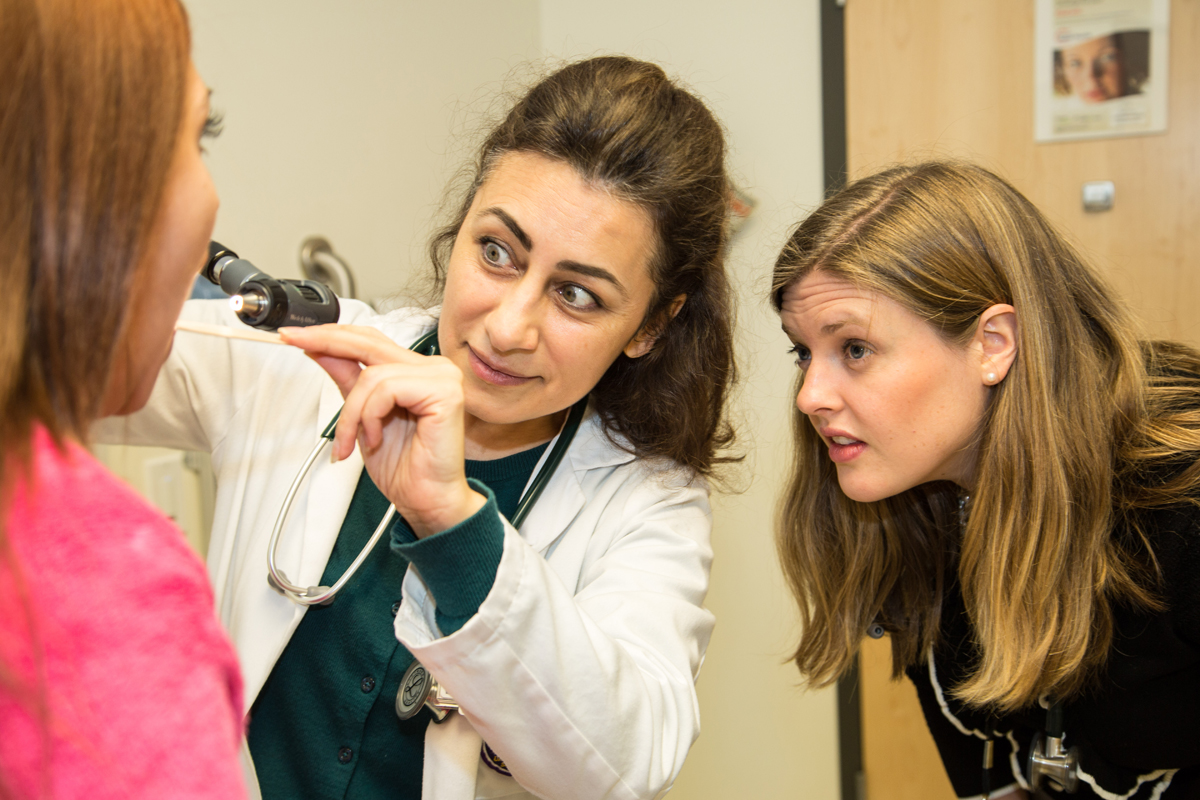

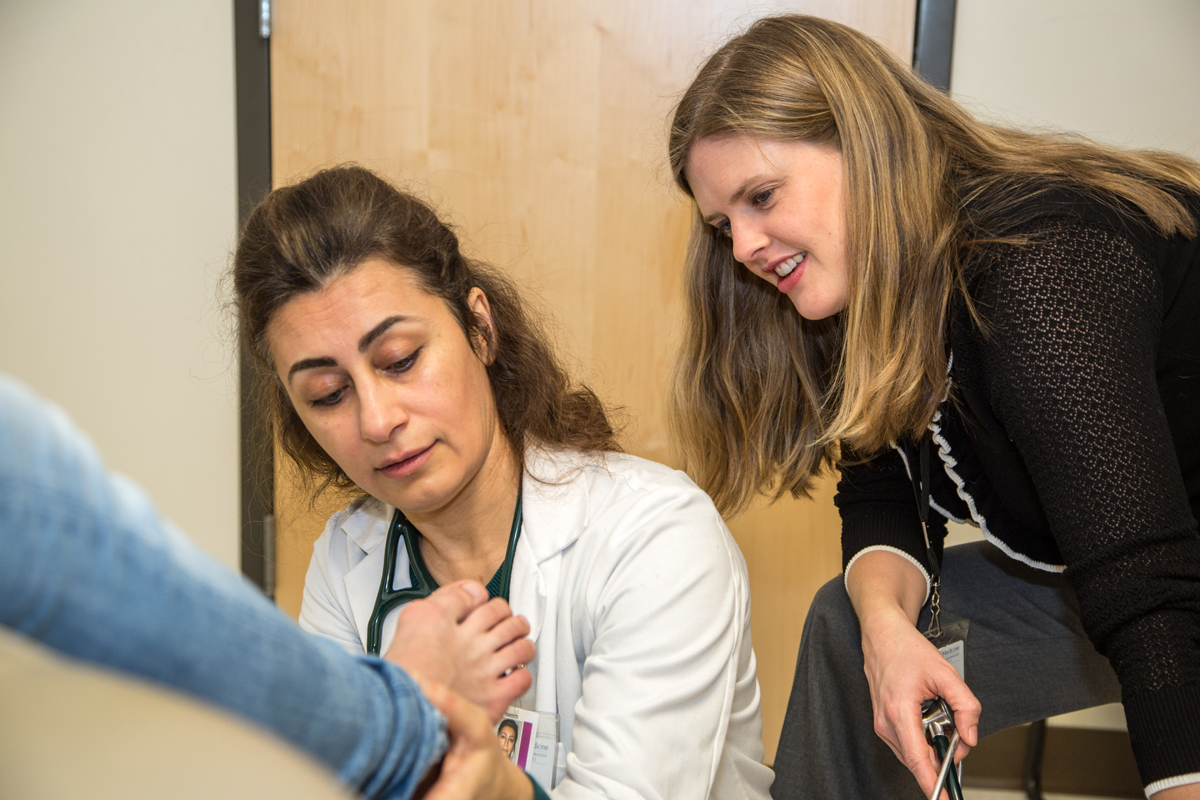

Despite the fact that the Northgate Clinic was the first assignment of her clinical year, Sepideh has duly impressed her preceptors. Bryna McCollum, PA-C has heaps of praise for her abilities and cultural competence.

Sepideh Makouei with her preceptor at UW Medicine Neighborhood Northgate Clinic, Bryna McCollum, PA-C.

“She’s done a wonderful job getting up to speed at this rotation,” says Bryna. “UW Northgate can be a challenging site because there are so many different preceptors. It takes a student who is really on top and proactive in their learning. I’ve really seen Sepideh come a long way, and her skill set, too. This is her very first rotation, and there’s been a lot of growth. For instance, she hadn’t done a lot of pap smears. I remember that was tricky when she first started. Now she’s a pro at it. It’s really fun to see the growth of her physical exam skills, and becoming more competent with assessments and plans too. Her language skills are amazing, I think that will be an asset to her in clinical practice as she speaks five languages.”

For the record, that includes English, Farsi, Turkish, Indonesian and Portuguese.

Bryna McCollum goes on about Sepideh. “She’s very empathetic, and she really has an excellent rapport with patients. Students come into PA school with a lot of life experience, and that really helps with empathy. I think that is really an asset when you’re relating to patients in a clinical situation. I teach a lot of medical students too, and they’re often younger and just haven’t had that life experience yet.”

Within her study group at MEDEX, Sepideh has shared some of the details of her immigration path. “We’ve gotten close, and I’ve shared some of this with them.”

As someone who demonstrated fearlessness when going up against authoritarian institutions in her native Iran, we wonder if Sepideh sees herself playing any kind of advocacy role as a healthcare practitioner in the United States.

“I would like to,” she responds.

Earlier, she had submitted a proposal to PAEA for presentation, but it wasn’t accepted. “I really lack in writing skills,” she says with some sense of disappointment. The paper was critical of how PAs are currently being contracted in rural settings with low pay and no job security. She also feels strongly about PAs students playing a greater role at UW Medicine. “This is an academic environment, and a wonderful place to have more PAs involved. But you actually see a lot less than elsewhere.”

For Sepideh and her Seattle Class 49 cohorts, graduation is coming soon. We inquire as to what kind of job she might take after her training at MEDEX concludes. Is she drawn to family medicine, or some specialty practice?

“At this point, whatever comes first,” she says. “I need to care for my family.”

With two children and elderly parents to support, practical considerations come foremost.