The following story is based on multiple interviews with, and recorded presentations by, Dr. Richard Smith, along with numerous interviews with colleagues, contemporaries and participants from the period of time being covered, as well as rigorous research into secondary news reports, professional publications, and archival resources.

Richard Smith, a young and deeply curious Howard University freshman, stood and observed a community health worker making her rounds. The year was 1951. The place, a community health clinic located in a Methodist missionary work camp in pre-Castro Cuba. Though Smith was no stranger to the economic struggles and ongoing racial discrimination that marked life for African-Americans in post-WWII United States, nothing could have prepared him for the degree of poverty and hardship that he witnessed there in the Cuban countryside.

Smith watched a small child with no diaper crawl across the rough clinic floor, sick with diarrhea. As the child moved, a large tapeworm emerged. Focused and full of questions, he watched the young community health worker tend to this infant, and then to the many other sick people in the clinic that day. What was the extent of her medical training? Less than a year of training, probably two or three months. Were there doctors available? Yes, though their numbers were limited. He knew that a doctor dropped into this clinic one, maybe two days a week, when possible. Otherwise it was this young woman, this one health care provider, who would care for those filing into the clinic, day in, day out.

What if there were others like her? Smith wondered. What if the answer to improved healthcare lay not simply in having more doctors, but in increasing the number of mid-level healthcare providers like this one? In multiplying her caring, skilled hands?

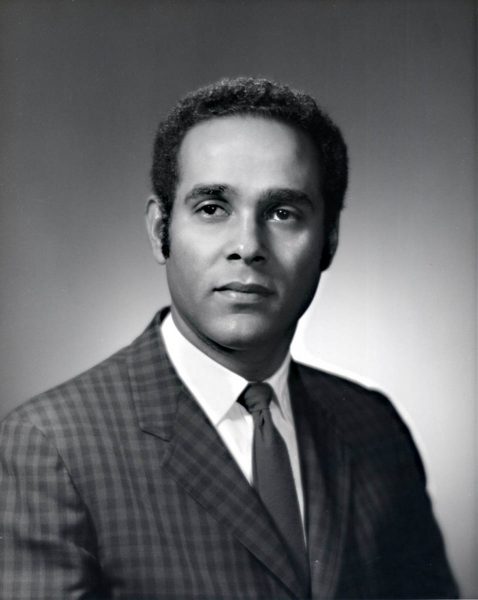

Many years later, it was this volunteer trip to Cuba that would stand out in Richard Smith’s mind not simply as a formative experience, but as the very moment that his long and illustrious career as a progressive healthcare visionary began. He returned from Cuba to Washington DC, and dropped his music major in favor of pre-med studies. His primary focus became parasitology. He entered the Howard University Medical School, and became renown for his expertise on mosquito and parasitic-born illness. His efforts came to the attention of the National Institute of Health, and Smith became the first medical student in the Public Health Service to become a Commissioned Officer. In 1957 Smith received his M.D. from Howard University.

The career of Dr. Richard Smith was underway, a career that would lead him down many paths and to many places, including Seattle, of course. But the memory of that small Cuban health clinic would never be left behind.

A Vision for Training People

Becoming a physician in the U.S. of the 1950s was a pathway to an affluent life. But Richard Smith’s interests lay elsewhere, and he deliberately sought out placements working with underserved populations. For years, Smith believed his goals could best be accomplished by working through The Episcopal Church, the church in which he had been raised. But he soon came to realize that the model on which the Episcopal Church’s missionary work was structured – doctors placed into communities to establish and oversee health clinics – was in many ways just the opposite of the vision he was developing based on the idea of “multiplying hands,” or what he began to call the “multiplier effect.”

“I did not want to be running a clinic,” Smith says. “I wanted to train people.”

“I did not want to be running a clinic,” Smith says. “I wanted to train people.”

In 1961, Smith turned to John Burgess, then the first African-American archdeacon of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, and asked him to carry a proposal to the World Council of Churches (WCC) being held in New Delhi that year. “What I was trying to say is that you can’t do anything with one person,” recounts Smith. “The multiplier effect had to be put into place. It was a full-scale public health approach—not just a medical approach.”

Archdeacon Burgess was a supporter of Smith’s approach. Ultimately, however, the WCC turned down the proposal.

Peace Corps Experience

A new direction came when the Public Health Service took charge of health care for Peace Corps volunteers. In 1961, Dr. Smith was invited to D.C. for a visit with Robert Sargent Shriver, the Kennedy administration’s driving force behind the creation of the Peace Corps. An international incident involving the Peace Corps had arisen, and Shriver saw in Richard Smith someone who could manage the situation. “We need you in Nigeria,” Shriver told him.

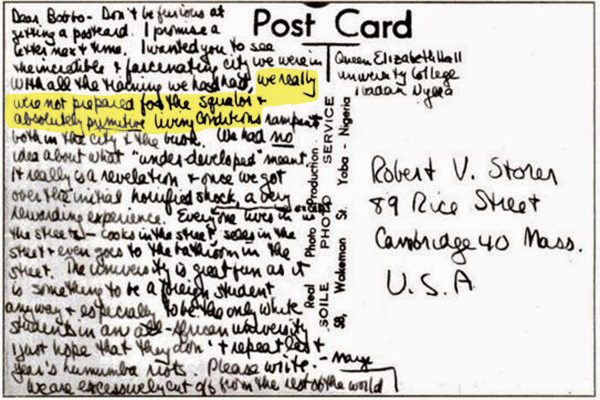

The Nigerian situation was complex—politically and medically. An American Peace Corps volunteer in training had written a postcard to a friend back home that noted the country’s “squalor and absolutely primitive living conditions.” Before the postcard was mailed, however, it was discovered by a Nigerian student, who was offended by its contents and preceded to distribute copies of it all over campus. Crowds gathered. Riots ensued.

Into this scenario stepped Dr. Smith as a Peace Corps physician in Nigeria. Smith’s primary assignment was to assure the care and safety of Peace Corps volunteers. His rounds took him from community to community, which were sometimes 200 to 300 miles apart. His medical counsel became gospel to volunteers living in areas afflicted with unfamiliar diseases.

But Smith also provided care to the Nigerian locals in several mission hospitals. It’s in that capacity that he trained “dressers”— people who were charged with changing dressings.

“I volunteered my time to train these folks in the bush—not in urban centers—but in rural missionary hospitals,” says Smith. “In each of those settings, I selected two people that seemed brighter than most. They just responded to me, and had enough English to operate. I trained them how to identify and treat two things—malaria and fever. They had to know how to listen to chest sounds.” These individuals were subsequently trained to treat diarrhea, dysentery, worms and malnutrition. Enough, that is, to cover 90% of Nigeria’s most common medical needs.

After a very short period of time, it became obvious to Smith that these former “dressers” were now taking care of most of the patients. With the memory of the WCC turning down his proposal still fresh in his mind, “I knew I was on the right path,” says Smith.

At the end of two years in Nigeria, Dr. Smith returned to the US in 1963, and was appointed to the position of Deputy Director of the Medical Program Division of the Peace Corps, with responsibilities for assisting in directing the health programs of more than 8,000 Peace Corps volunteers serving in forty-six countries.

The Beginning Ideas of MEDEX Emerge

In 1965, at the conclusion of his time with the Peace Corps, Richard Smith was asked by Dr. William H. Stewart—the 10th Surgeon General of the U.S.—to join his staff as the Director of the Office of Planning for International Health. Smith took the job, which included his becoming a US delegate, the youngest ever, to the World Health Organization (WHO) Assembly in Geneva.

Once there, Smith made it a point to identify the Assembly’s key players, a habit that would continue to serve him over the years. Here they included Melvin Laird, then head of the House Appropriations Committee, Lyndon Johnson’s personal physician Jim Cain, MD, and Gerald Dohrman, who later became President of the American Medical Association (AMA) from 1969-1970.

In the meantime, Smith’s boss Dr. Stewart visited Southeast Asia with Eugene Black, Special Adviser to the President on Southeast Asian Social and Economic Development. The message they returned with was “We need doctors.” Propelled in large part by the intention of winning over the hearts and minds of the local populations of the region through improved access to healthcare, Bill Stewart returned to the US, walked into Smith’s office, and said, “You know this crazy idea you have about physician extenders? I think we can put this together.”

The term “physician extenders” had become increasingly common in discussions of doctor shortages. Its meaning is mostly self-evident: personnel with less sophisticated but nevertheless skilled training could provide needed healthcare services where physicians weren’t available. For Smith, the concept of physician extenders aligned with his earlier experiences in Cuba and Nigeria, and echoed his own developing ideas on the matter.

Stewart presented Smith’s ideas to area officials. “They thought it was a good idea,” recalls Smith, “and wanted to know why we weren’t doing it in the US.” Their question caught Dr. Smith’s attention. Up to that point, he had envisioned the use of community health workers mostly as a solution in international settings. But now he began to wonder, why in fact weren’t we doing it in the US?

During his tenure with the World Health Organization, Smith had also become familiar with something known as the “Feldsher system” that had emerged from the Soviet Union, with roots reaching as far back as the time of Peter the Great. Fundamentally, Feldshers were mid-level medical practitioners used by the military to provide healthcare to wounded soldiers and civilian populations across the Soviet Union.

The notion of applying the Feldsher idea to problems being faced by the United States—problems tied primarily to considerable gaps in healthcare access, especially in rural areas—was not lost on Richard Smith. “What I had to figure out was how to do it outside of the Soviet Union,” he said.

The seeds of what would become MEDEX were sown. But there was another significant career milestone for Smith before the concept could be fully realized in the US.

Desegregating the Nation’s Hospitals

While working for the US Public Health Service in 1966, Dr. Smith was assigned as Director of Operations for the desegregation all hospitals in the United States. Desegregation was a required component of the implementation of the newly created Medicare program. In February of that year, the Surgeon General created the Office of Equal Health Opportunity (OEHO) as the agency specifically responsible for certifying that hospitals wishing to become Medicare providers were in compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

Smith at the far right while on the staff of the 10th Surgeon General of the U.S., Dr. William H. Stewart. Dr. Stewart, who assigned Smith as Director of Operations for desegregation of all US hospitals, is seated centermost.

The nation’s hospitals would have to be certified compliant by July 1966, in less than six months time. This meant that minority patients could no longer be denied access to any service provided by the hospital, or to any part of the hospital. Patient rooms, cafeterias, rest rooms, and even the blood supply had to be integrated. Qualified minority physicians, minority residents, nurses and medical technicians could no longer be denied opportunities. “We had less than one year to desegregate thousands of hospitals,” says Smith. “It was the fastest thing I’ve ever seen. We didn’t have much time.”

Prior to the national desegregation of hospitals, whites and blacks had separate entrances, waiting rooms, care wards and blood supplies.

The authors of Medicaire and Medicaid at 50: America’s Entitlement Programs in the Age of Affordable Care, take Smith’s description a step further, calling it “the highest-stakes poker game in the history of federal domestic policy.”

“On March 4, 1966,” they write, “every hospital in the country received a letter over the Surgeon General’s signature describing the guidelines for compliance.” The letter further required hospital administrators to sign and return assurance forms in a week’s time, and detailed upcoming compliance visits. “Representatives of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare will be visiting hospitals on a routine periodic basis to supplement this information and be able to offer further assistance in resolving any problems that may arise.”

About 1,000 volunteers were transferred to HEW in support of this effort, and Dr. Richard Smith was given jurisdiction over them. They did not, however, represent a random slice of HEW employees. “Many were already involved with the civil rights movement and saw the temporary voluntary transfers as an opportunity to incorporate their activism into their day jobs. No one had to be drafted.”† Training centers were established in Atlanta and Texas. Levels of volunteer training varied. Some attended hastily arranged two-day training sessions, while others learned the job on the fly.

In the midst of all this, Smith received a phone call from Vice President Hubert Humphrey, whom he had met previously at the White House Conference on Health in November of 1965.

“President Lyndon Johnson wants you to go to Marshall, Texas—Ladybird’s home town,” Smith recalls Humphrey telling him. “He wants to send a message that he’s deadly serious, and he wants the message to be loud and clear.” So Richard Smith was sent to Texas as a walking message from the President that desegregation’s time was now.

President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Medicare bill into law on July 30, 1965. Desegregation of all hospitals was a required component of the Medicare implementation.

A Dangerous Time

“When I went to Marshall, I thought I was going to be killed,” Smith recalls. And in fact it was a dangerous time. In the news was the story of a white female internist who had been reporting on the situation within the hospital during this time, and was assassinated in her Mobile, Alabama home.

Everyone knew why Smith was there in Marshall. The Texas Rangers would not venture into the hospital. He met with the hospital’s Board of Directors, who told him that they were not going to desegregate. “You’ve just kissed $100 million bucks goodbye,” was Smith’s response. On Monday, Smith got a call from the Chairman of the hospital’s Board of Trustees, who reported to him that they had hired a new administrator.

Smith then received word that Lyndon Johnson was traveling to Baton Rouge the following Tuesday, and the request that the hospital there be desegregated by the time of the President’s arrival. So he turned his attention to Baton Rouge. An administrator there told him, “We can’t desegregate our hospital. Last year we tried to desegregate our community swimming pool, and they blew it up.” Still, Smith pressed the issue.

“Who do you report to?” the administrator asked.

“The Surgeon General,” Smith replied.

“And who does he report to?” asked the administrator.

“The President of the United States,” said Smith.

Twenty minutes later, the Baton Rouge hospital administrator called back and asked, “Okay, what do we have to do to desegregate?”

During the desegregation assignment, the Surgeon General’s office uncovered subterfuge at HEW—the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare. There was tampering with the mainframe computers at HEW to get certain hospitals off the targeted list. “The government had to put one of their staff in there each night to stop this,” says Smith.

To break the resistance, Surgeon General Bill Stewart prosecuted five hospitals. “We won these first five cases, and everything else collapsed after that,” reports Smith. It was also necessary to close a number of black hospitals because they were segregated.

On reflection, Richard Smith views this desegregation experience as the source of enlightenment and encouragement that allowed him to moved forward with the burgeoning MEDEX concept. As Smith summarizes it, “Here was an idea that took into consideration those for and those against, and how to change attitudes in order to move a social effort forward.”

The MEDEX Vision Clarified

At the conclusion of the yearlong desegregation effort in 1966, Smith’s job with the OEHO changed to more of a caretaker role—something that didn’t particularly engage him. He was instead becoming increasingly interested in putting his visions concerning expanded healthcare into action.

“My vision was clarified,” says Smith. “I kept going back to the way that change was affected during my early days in Cuba and Nigeria. They represented something for me. They represented possibilities. What I had been learning was the world in which these possibilities could occur. I was amazed at how clear it was, at what had to happen. And I was also afraid it was a dream I couldn’t pull off.”

Smith knew he wanted to pursue this dream on the West Coast, but to do so from within the auspices of US Public Health. Bill Stewart gave his blessing, but with one catch: Smith could remain in the Public Health Service, but he would be put on leave without pay.

Stewart was getting a lot of flack from Congress concerning the Public Health Service’s role in desegregating thousands of US hospitals, and in particular Smith’s role in this as Director of Operations. “He found out that there was tremendous opposition to desegregating the hospitals, but he supported me thoroughly through all this,” says Smith. “When we had finished, he felt pressure from a lot of people on me. He said, ‘It’s better if you go.’”

A Path For Medically Trained Military Personnel

Already familiar with the leadership at University of Washington in Seattle, Smith wanted to leverage that to develop a pathway for the vast numbers of medically trained military personnel to reenter civilian life with a qualified career as mid-level health practitioners. At that time the concept was discussed as “physician extenders,” perhaps to soften the blow to the established medical profession. Smith approached Dr. John Hogness, Dean the UW Medical School. “John Hogness thought it was a crazy idea,” Smith recalled, “but one that sounded intriguing to him.”

Unbeknownst to Smith, a similar initiative had started two years earlier at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Eugene Stead, the Chair of the Duke Department of Medicine, launched the first physician assistant program to fill the gap between nurses and physicians. In 1967, Duke graduated its first three PAs from the fledgling program. “If I had known what Dr. Stead was doing, I would have gone down to see him,” says Smith. Instead, Smith was getting input from the Surgeon General, AMA President Gerald D. Dorman, Ted Kennedy’s medical advisor Dr. Lawrence C. Horowitz, and a host of Peace Corps docs that Smith had worked with over the years.

Deputy Director

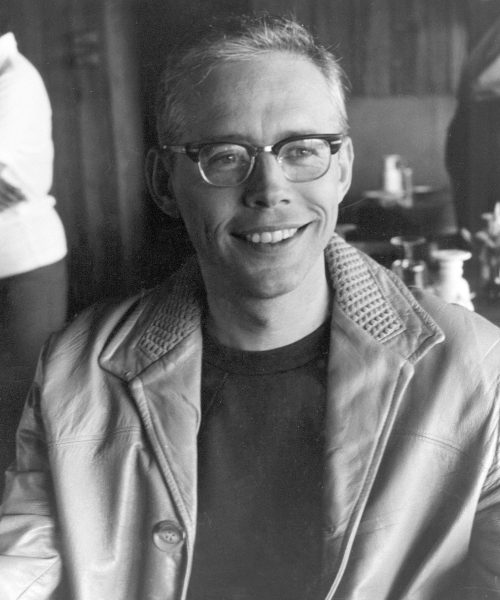

Dr. Gerry Bassett and Richard Smith had crossed paths when they were both commissioned officers with the US Public Health Service. Upon meeting again in 1969, Bassett was teaching and working in research at the UW School of Medicine in what would later become the Department of Public Health—Preventive Medicine. He was also working part time as the Director of Environmental Health and Safety for the university.

“Dick showed up at the University of Washington,” says Bassett. “He had this idea way back when, as he can tell you. He began to talk with me about what he had in mind.”

Basset had three years with the Navy as a Lieutenant JG (Junior Grade) on aircraft carriers in Korea. Grasping the value of Smith’s concept wasn’t a big leap. He understood the target audience for this program.

“These are former military corpsmen, highly skilled and trained,” says Bassett. “We’re not talking entry level. We’re looking to get people who already have training and experience to continue that in the civilian area. Really, there wasn’t much for them except to go into academic programs for another one or two years or more. Mostly, these trained corpsmen had already been through a lot of that stuff. So we figured, why not capitalize that, and find out what they’ve learned, what they can do, and put it to immediate use—filling in the holes of what they don’t know, what they hadn’t done. That was the basis of it.”

Gerry Bassett came aboard as the Deputy Director. “I hired him to be in charge of the curriculum,” says Smith. “It’s got to be a competency-based curriculum,” meaning that the students would have to be able to demonstrate their knowledge, both previously acquired as corpsmen and newly acquired through the program.

Then there came the question of what to call the program. Smith said to Basset, “Well, don’t you know, this is kind of an extension of medicine”. Together, they kicked it around and, according to Bassett, Smith came up with the following wordplay. “Here, how about this: extension of medicine, medical extension… MEDEX!”

Then there came the question of what to call the program. Smith said to Basset, “Well, don’t you know, this is kind of an extension of medicine”. Together, they kicked it around and, according to Bassett, Smith came up with the following wordplay. “Here, how about this: extension of medicine, medical extension… MEDEX!”

Together, Smith and Bassett put together the idea of a core staff and began looking around for sources of funding.

Hiring Staff

By June 3rd, 1969, a small faculty and staff were hired for the federal demonstration project known as MEDEX Northwest. Offices were located just off-campus in the University District Building at the corner of NE 45th Street and 11th Avenue NE.

The very first staff hire was Carolyn Robbins and, a bit later, Lorna Carrier. “Lorna and Carolyn were key staff members,” recalls Bassett. “We wouldn’t have gone anywhere without them.”

There was a third administrative support person who didn’t last long. “I had a secretary, and she was overwhelmed,” recounts Smith. “Then this 21-year-old girl came into my office named Lorna. She came in, organized our office, and the 43-year-old woman who was overwhelmed, left.”

Lorna recalls the accelerated stride during the initial years at MEDEX. “It was very exciting,” she says. “Some people who came to work for MEDEX left after the first day because they couldn’t take the pace. We didn’t have coffee breaks. We just rolled and really enjoyed it. It wasn’t stressful, like we had to do it. We wanted to be doing it. I think our enthusiasm would spread.”

“Things were moving pretty fast at the time,” adds Gerry Bassett.

Key among the early MEDEX staff was Bill Freeman, who came to Smith’s attention while at the Surgeon General’s office. “My colleagues in the Peace Corps called me and said, ‘There’s a Green Beret corpsman here in our office. We think you should talk to him.’”

At first meeting, Smith describes Freeman as “this runt of a guy filled with knowledge and experience. His father had been a pathologist, and Bill had been in the Peace Corps in Columbia. He told me what he did on the battlefield—suturing and transfusing people. Bill was MEDEX. He told me, ‘If you ever get this thing funded, I’d like to work for you.’”

At the start of the project there was no funding, so Freeman agreed to come onto the MEDEX project for room and board. He moved in with Smith and his family. “I was still a growing boy at age 26-27, and I nearly ate him out of house and home. Dick couldn’t believe how much I ate.”

Freeman served in the Peace Corps from ‘62 to ‘64 in the city of Cartagena, Columbia doing community development work. Later, he joined the US Army Special Forces to go to Vietnam and work among the indigenous Hill Tribes. “This was a time of cold war Kennedy-style liberalism,” says Freeman. “His two pet organizations were the Peace Corps and Special Forces.”

In Vietnam, Freeman trained as a medic. The technical title was a Special Forces Aid Man—an independent duty medic. “I had a years training to function like a physician where there was none in a very resource-limited environment,” he says.

At MEDEX Freeman was given the title Associate Director. He supplied the knowledge about what candidates could do, and therefore, what did not have to be taught. He also knew what was missing for these candidates to function in a similar situation but with a physician either out in the rural areas or the inner city. “I participated in screening of possible applicants,” says Freeman. “But my main job was to help develop a curriculum that relied on what they already knew, and taught them what they didn’t know but was necessary for their setting.”

Another essential addition to the staff was Carnick (Mark) Markarian (1925-2014) who served as Deputy Administrator. A sailor in WWII and Captain in the US Public Health Service, Markarian had trained pharmacist’s mates and was experienced in administration and finance in Washington, DC. “He was an everyman in the grants and applications area,” explains Bassett.

Dr. Raymond Vath completed the core staff. “We thought it would be reasonable to have a psychiatrist onboard to better understand how are potential candidates were put together,” says Bassett.

The program recruited a couple of educators—Gary Dunn and Bill Wilson. “EdD educators, we’re not talking PhD educators,” explains Bassett. “We picked up these educators as we went along to get some input on how people learn, what teaching methods could be used. We didn’t want to jump into a high-powered academic masters PhD, that kind of thing.”

“There were others that came in and out too, but those were key,” says Bassett. “We had a marvelous group. It took a different mix of people—people that could sit around, get ideas, and not worry about their egos being stepped on. Here are people who could concentrate on getting a job done without getting egos and personalities in the way. That’s not easy. I’m not sure we called ourselves that at the time, but we were doers. We were thinkers. We went from the thinking to the doing. Our staff meetings were free, open and rollicking.”

Apparently the group was not in the habit of taking formal meeting notes. “Never for a minute did it occur to us that people would be looking back at us,” says Lorna. “We didn’t document.”

As a footnote, the tight intensity of this group of thinkers and doers had effects beyond the creation of a new medical profession: two enduring marriages came out of the birth of MEDEX. Bill Freeman and Carolyn Robbins eventually wed, as did Dick Smith and Lorna Carrier in 1976.

Engaging the Support of Rural Communities

For funding, Smith applied for $700,000 from the RMP, Regional Medical Program. But there was resistance, or rather, a lack of understanding.

Smith talked to the Washington State Medical Association, and they didn’t know what to make of his MEDEX proposal. From his experiences with desegregation of the nation’s hospitals, Smith knew that he had to sell his idea as the solution at the points of greatest fracture. He requested a list of the most overworked doctors in the state. These were all located in rural areas—small towns in Eastern Washington like Tonasket, Odessa and Othello. Smith contacted these physicians, and arranged town hall meeting in their communities. “I set my targets on the docs who needed help the most. This became the MO,” he says. “We’d go into a town where the doc was planning on leaving. The doc would stand up and say, ‘I hadn’t told you yet, but I was planning on calling a moving van.’”

The doctors delivered the message, and Smith would explain the scenario. The towns wanted to know what they could do.

“I was flying by the seat of my pants,” Smith says. “When I stood up to lead these town meetings, it was really amazing. Most of them had never seen a black man.”

“I was flying by the seat of my pants,” Smith says. “When I stood up to lead these town meetings, it was really amazing. Most of them had never seen a black man.”

Smith knew that he had to identify the people who were for and against the concept of outside help in the form of trained Medex, as they were called at the time.

“What we were after is a systems change,” Smith says. “This whole idea is what became known as the receptive framework. What I wanted to do was to create an irresistible force such that, if you went against it, you’d have to face the whole town. If you get people to invest in town hall meetings, and demonstrate how each of them benefits from what you’re trying to pull off, you make them accountable. They will make it work.”

Smith had brought psychiatrist Dr. Ray Vath onto the MEDEX staff to help manage change.

Speaking of Dick Smith, Dr. Vath said, “Here’s a guy who’s organized and understood the issues that need to be dealt with. He was very careful about information, who got what, where, when, and how. When you’re trying to get change, a lot of people are going to oppose us. He told me, ‘That’s why you’re here, because we need psychiatrists here to overcome resistance to change.’ That’s what psychiatrists do”.

Vath recalls one pocket of potential resistance in Spokane, WA that they had to overcome.

“Dick and I were presenting to the Spokane Medical Society,” says Vath. “After Dick’s presentation, a doctor got up and said, ‘I think this is a communist plot and we need to squelch this immediately. It’s out to destroy the practice of medicine.’”

Dick turned to Ray Vath and asked, “What do we do?”

Vath said to Dick, “Let me try.”

Dr. Vath stood up. “You know, I have concerns too. I’m not sure if this is a good idea either. It’s too early to tell. But when it comes to loyal Americans, I just got out the military after ten years active duty and four years in the reserve. I don’t think my loyalty is going to be in question.”

Vath continued to preempt the concerns of the doubter. “Let me tell you, we need people like you to watch our program. And if you see us doing something dangerous to anybody, I want you to call me personally. Here’s my card with my name and number. Because I can destroy this from the inside quicker than you can destroy it from the outside.” That man became a MEDEX supporter and the next president of the Spokane Medical Society. There was no resistance.

In every town there were a lot of questions, but there wasn’t a single detractor. During the late 1960s, the doctor was the most powerful person in a small town. “Doctors understand transformation and how to change the mindset of people,” says Smith.

Eventually Dick Gorman, the Executive Director of the Washington State Medical Association, assigned one of his staff, Roth Kinney (1920-2006), to work directly with the MEDEX team. “Gorman knew these docs were in trouble,” says Smith. “They were overwhelmed. He told me, ‘You can sell them anything.’”

At the same time, Smith and his team were recruiting these same small town physicians to become preceptors—to assume an active role in the MEDEX Northwest students’ clinical education outside of the classroom. And part of the deal was that the preceptor/physician would hire the student once they graduated. “Every Medex had a job before they were recruited,” says Smith.

The Quest for Funding

Despite this, funding remained out of reach. The Regional Medical Program (RMP) met to discuss Smith’s $700,000 proposal request. Smith wasn’t present for the RMP meeting where the MEDEX funding was discussed. Word got back to Smith on the controversy. One individual in the group said he “didn’t want any black bastard getting his hands on this much federal funding”. Two staff members resigned on the spot in protest.

Later, these two staffers contacted Smith, and he went to lunch with them. “They were in tears because they saw the value of this program, and they were enthusiastic about it. I told them, ‘We’re going to get our money. Don’t worry.’”

That night Smith called Surgeon General William Stewart, Joe English and Dr. Stan Shirer from HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). “It took exactly 30 minutes with Stan and Joe for me to get three quarters of a million dollars from HRSA. What sold them was the fact that we had done our early preparation.”

Recruitment Begins

In mid-1969 the MEDEX Northwest program was underway, and recruitment could begin.

Visits were made to a number of Army, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard installations to inform groups of corpsmen about the proposed project, and to elicit applications.

“We tended to gravitate towards the Special Forces corpsmen because they had the best training and the most independent medical work, often behind enemy lines in the mountains of Vietnam,” says Ray Vath.

Smith traveled to a number of military training institutions, including Fort Bragg where they train Special Forces corpsman and the Naval Hospital in Bethesda. “The Special Forces corpsman and Navy Seals have this tremendous medical training, like 1800 hours of training,” says Smith. “Air Force corpsman and Navy corpsman also had tremendous training. That was going to be wasted in the civilian sector if something like this didn’t happen.” Word got out.

80 applicants were screened, and 26 candidates were interviewed for the demonstration project. From that, fifteen students were selected to be part of MEDEX Northwest Class 1.

One of Smith’s objectives was the underserved populations of the US, so he thought it was necessary to recruit from minority groups.

“In that first group I wanted to find, at least, an Hispanic and a black,” he says. This proved rather difficult because Medex was an untried profession. “Most of the people I talked to were not interested in getting a job that wasn’t going to be guaranteed.”

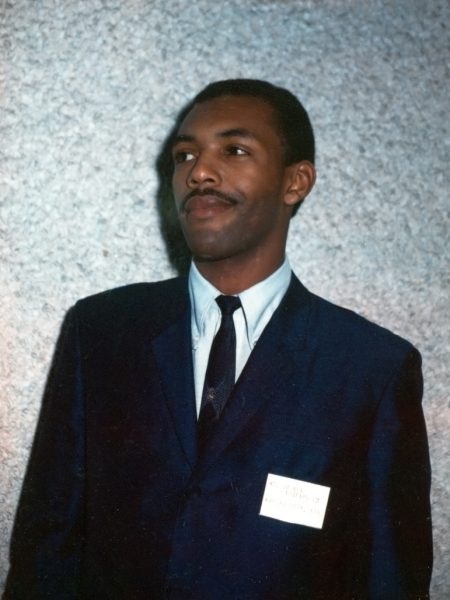

Steven Turnipseed, MEDEX Class 1

Smith found his sole African American candidate working as a MTA at Leavenworth Federal Prison where he was treating life-term inmates. In the late 60s, an MTA or Medical Technical Assistant operated much like a physician assistant within the Federal Bureau of Prisons Health Department. Turnipseed was back in the States from 10 years in the US Army, his last duty assignment with the 1st Special Forces Group in counter-intelligence and psychological warfare in Northeast Thailand along the Cambodian and Laotian borders. Early in his military career, Turnipseed received advance training as a surgical tech, a radiological tech and, later, as a medic to accompany the Special Forces team.

“Someone called me on a Sunday night,” recalls Turnipseed. “He said, ‘Hi, this is Dick Smith. “I’m really interested in you coming out and looking at this new program we have called MEDEX.’ He tried to explain to me a little bit about the dynamics of what he was trying to do, where he was going.”

Turnipseed listened, took it all in and went back to his colleagues at the prison. “They all looked at me and said, ‘Are you crazy? That will never fly. Once you get outside the prison where you have the protection of the Federal jurisdiction, there’s nothing to cover you. No person—no doctor, no nurse, no patient, would accept a Medex. You just can’t do that. People don’t want that.’”

After three or four days of deliberation, Turnipseed made up his mind to apply to the MEDEX program. His coworkers at Leavenworth said, “Well, okay Steve. We expect you back in about three months. You’ve got a GS18, and that’s pretty high. You just can’t get out of this.”

In Seattle, Turnipseed met Dr. Richard Smith in person. “Dick is a unique individual in himself because he was so passionate, and he was so knowledgeable. When he talked, things happened. People believed in him, and they followed him. He became my mentor. I followed him, and this is how we got to where we are today.”

Smith describes Turnipseed as “one of the most wonderful human beings I know. He had incredible skills, both people skills and medical skills.” Steve spoke fluent German and Spanish, despite the fact he didn’t have a high school education. Later, Steven Turnipseed got his GED and received his bachelor’s and a master’s degree in Public Health.

During the preceptorship phase of his MEDEX education, Steve was placed in an urban Seattle hospital setting—Group Health Central on Capitol Hill. He worked there for a number of years, ran an outpatient clinic and developed a highly successful addiction treatment services program.

In 2006, Group Health created the Steven Turnipseed PA-C Award, an annual honor recognizing outstanding service among one of the 136+ individual PAs currently working at Group Health.

John Betz, MEDEX Class 1

The US Navy had supplied John Betz with his initial medical training. “After three years of college, I joined the Naval Reserve, and went to Great Lakes, Illinois, for boot camp,” he says. Betz was accepted into the Hospital Corps School, and then sent to a receiving station in Philadelphia to work with patients. “I had the good luck to end up at Bethesda Naval Hospital, which is a wonderful place to work.”

At Bethesda, Betz started out on the pediatric ward and, after a year and a half, made senior corpsman on the pediatric ward. Betz worked there until the end of his six-year enlistment. He stayed at the Naval Hospital, but switched to the allergy clinic as a civilian allergy tech. “I made allergy serums, skin tested people, and did that sort of thing,” he says.

One day Betz was introduced to Dr. Richard Smith, and the trajectory of his life changed forever. A woman who had set up John’s tuition payments to the University of Maryland was showing Smith around the Bethesda hospital. He was searching out candidates for his MEDEX program. Betz was mistakenly identified as someone studying to be a doctor. Dick said “Well, bring him over here, let’s talk to him.”

Smith spelled out his vision of the MEDEX program, and the role of physician extenders. “He said they were really looking for retiring chiefs with 20 to 25 years experience, but here’s an application. Fill it out, send it in, and we’ll see what happens.”

Betz received a positive response to his application, and was invited to Seattle for an interview before the selection committee. In Seattle, John roomed for the weekend with Tom Coles, a fellow candidate, Army Medic and Green Beret who served in Vietnam. Tom told tales of above the knee amputations and C-sections in the jungle without a tent. John thought, “I’m never going to get in this program. I took care of babies with ear infections, pneumonia and the like.”

Dick Smith deployed a rigorous approach to group interviews from his years in the Peace Corps. The candidates stayed together in small groups as they moved between different interview panels. “We had two days of interviews, every 15 minutes,” says Betz. “You got a schedule of different hotel rooms, and you would walk in, salute, sit down, sit up straight and say, ‘I like small towns, my wife likes small towns,’ and then answer their questions.” By design, the selection committee was stacked with small town practicing physicians who had a vested interest in the outcome.

It’s useful to note that Smith paid the greatest attention to the screening of wives. Because he wanted the MEDEX candidates to go into underserved areas, the spouses would help determine placement. “If a spouse grew up in a rural area or grew up in an urban area, we felt that they would be comfortable going back to that,” says Smith.

“They sent us all home, then got together and had a meeting,” Betz says. The committee decided whom they were going to accept, and sent us a letter shortly after that. I got accepted to the first class.”

Years later, Betz himself became part of the MEDEX selection committee process. In 2015 John Betz retied after 44 years as a physician assistant in the rural Eastern Washington community of Othello. In that same year he became the first PA to receive the UW School of Medicine Alumni Service Award.

Strategies For Educational Change

By design, the 1969 MEDEX curriculum model was developed as a short course. The high-level medical skills acquired in battle or even Stateside during the Vietnam War era did not translate into qualified employment out of service. Returning medics or corpsmen might find a job changing bedpans but, by and large, anything more would mean a return to school. And yet these returning veterans often had more hands-on medical experience—including life and death—than any medical student in an academic setting.

With all fifteen students sharing extensive medical background through the US military, the MEDEX didactic phase was trimmed to three months. After a brief classroom phase, the emphasis was on getting the students into the field for 12 months, working in family medicine under the preceptorship of the already primed and receptive small town physicians.

One of Dr. Ray Vath’s duties was to assess the psychological states of the fifteen MEDEX students.

“Out of the IQ tests we found our corpsmen all had above average verbal IQs, but their performance IQs were well above average,” says Vath. “In my field, that’s considered creative. The psychologist we talked to said these people are better at seeing and doing rather than reading and thinking. On-the-job-training was developed by the military. These guys can go from the laboratory to the books. But they don’t go from the book to the laboratory, which is the classic medical school model.”

Part of what Vath did was to help the returning servicemen in reintegration, especially around issues like PTSD. Vath prepared the MEDEX students on how to make a new dynamic in a field that was going to be resistant. “He helped us understand what our role was, and how to develop it,” says Steve Turnipseed.

In turn, Vath discovered an unexpected aspect of character from these fifteen corpsmen during a time of personal crisis.

In the first year of MEDEX, Ray Vath and his wife lost a baby in childbirth. “It was the most painful thing we’ve ever been through,” says Vath. Among all those who offered their sympathies—ministers, friends, family, colleagues and patients—the most effective were the corpsmen.

“Those guys, they had an empathetic understanding of the pain I was in,” he says. “I thought about it afterwards and realized, these guys had others die in their arms. That’s what the military does. They kill people. Somehow, their presence was so comforting. I learned so much about grief and comfort from these guys. That’s what I wanted to see in the MEDEX that evolved. It’s continued to this day, as PAs still are the most compassionate part of medicine.

Movers and Shakers

There was a little downstream problem. Outside of the cover of the University, it was illegal for these new Medex to practice medicine. Smith had to rally some broad systemic and legal changes before these fifteen students could practice medicine.

Smith put out a call to meet with the executive directors of all the US state medical associations. At the same time, doubt came to mind. “I wondered if I was in over my head,” says Smith. “Am I overstepping my bounds with the AMA?”

Smith called his old friend Gerald Dorman, then the AMA president. “No, the time is right,” Dorman said.

In 1969 the AMA held its annual meeting in New York, where Smith addressed the directors of all the state medical associations. Explaining the MEDEX model, he told them “This is the future. We have got to be a part of it, or get run over by all the problems that occur.”

The crowd bombarded Smith with questions. “I couldn’t answer all of them,” he says. “But they started coming up with the answers themselves.”

The Path to Regional Legislation

On April 15, 1971, Washington governor Dan Evans signed enabling legislation that would allow trained physician assistants to practice medicine to a “limited extent.”

For a fee of $50, any physician licensed in the state could apply to the State Board of Medical Examiners for permission to use the services of a specific PA. Chapter 30 of Senate Bill No. 182 specified “each physician’s (sic) assistant shall practice medicine under the supervision and control of a physician licensed in this state, but supervision and control shall not be construed to necessarily require the personal presence of the supervising physician at a place where services are rendered.”

But there was a period when both the Medex and their preceptor/employer/physicians functioned for a time without legislation. “This was a gutsy move by all concerned—MEDEX, the MDs and Dick Smith,” says Bill Freeman, MD, MPH, CIP, and current Program Director at the Northwest Indian College, Lummi Nation.

The work to win this legislation was significant. Smith’s efforts to create a “receptive framework” paid off. He had laid his foundation of support in the small rural Eastern Washington communities where the need was greatest. According to Bill Freeman, Dick had deliberately solicited MDs who were influential leaders in the Washington State Medical Association as well as with the Washington State Legislature—people like Dr. Bill Henry of Twisp, Kenneth Pershall and Richard Bunch of Othello.

Washington State Governor Dan Evans signed into law the MEDEX enabling legislation on April 15, 1971. Smith is pictured to the left of the seated Governor.

“Dick was very smooth and knowledgeable about getting some of the preceptors who were politically powerful in the WMSA and/or state politics in general,” say Freeman. “These were powerful people. They had first-class experience with MEDEX in their preceptorship. So when they spoke about the need to have MEDEX to the State Legislature—when they were lobbying for this legislation—these were important people who could help influence folks.”

But for the first MEDEX class there was a gap of 7 months between the end of their 12-month preceptorship in September of 1970 and the enabling legislation of April 1971. How did the newly trained Medex legally work within their assigned communities?

Jack Lein, the UW legislative liaison, pointed out that the Medical Practice Act allowed for UW medical students to practice a limited form of medicine under supervision while they were trainees.

Smith remembers Lein’s solution to bridge the gap. “The law said that a trainee at the School of Medicine at the University of Washington is exempt from the Medical Practice Act. The next day I saw Dean Hogness and said, ‘John, I want a letter from you to every MEDEX student. I want you to begin it by saying, ‘Dear Trainee.’ He did that, and as soon as they got this letter, they became legal– for 9 months. Until they were no longer trainees, until the program ended. So I had 9 months in order to get the legislation passed. That was the window we had to work with.”

There was another ingenious stroke at work. The final legislation retroactively covered the Medex’ work at the end of their preceptorship. “It was a retroactive coverage,” says Freeman. “If that had not been included the plan was simply to extend the preceptorship until the point of the enabling legislation. The medical school was ready as a fallback position.”

Steve Turnipseed, PA-C, recalls the uncertainties of the new profession at the time. “All during this process there was no enabling legislation or concept about what a PA could do or what a PA was. We went through the whole training program—the preceptorship, the concept, everything. But lo and behold, we had to delay graduation because we didn’t have enabling legislation. This is when Dick, Roth Kinney, others and the Legislature got together and implemented the enabling legislation. But we were already in practice and doing what we did very well.”

During this period of uncertainty, Smith’s advance work with the rural doctors paid off. “The development of what we called the receptive framework for this began by working with these physicians that were in trouble,” says Smith. He would learn which physicians had ties to representatives in the State Legislature, and invest in these physicians—with student clinical placements—so that they would talk to their legislators.

How This Played Out With Nursing

When the HRSA funding for MEDEX came through, Smith received a call from Hildegard Peplau, the President of the American Nurses Association. Peplau was well-known for her Theory of Interpersonal Relations, which helped to revolutionize the scholarly work of nurses. Nurses all over the world valued her achievements and she became known as the “Mother of Psychiatric Nursing” and the “Nurse of the Century.”

Peplau requested a meeting with Smith about the MEDEX program, and flew to Seattle.

“She told me she thought this is not something we should do,” recalls Smith. “I said, ‘I’m sorry, but this is what I want to devote my life to.’”

Smith reports that Peplau got up, walked into another room where she had already called a press conference, and “began lambasting me about what we were doing”.

In the meantime, Smith had gained the backing of the Washington State Nursing Association. “I was very open with them, including them in how were going to get the legislation, and that that we were going to train nurses if they wanted.”

Bill Freeman recalls Smith’s efforts to overcome any potential opposition from nurses within the state. “MEDEX met more than once with the leadership of the State Nursing Association, typically accompanied by the WSMA as well. Very purposefully Dick included Nurse Practitioners in the final enabling legislation.”

Efforts on the National Front

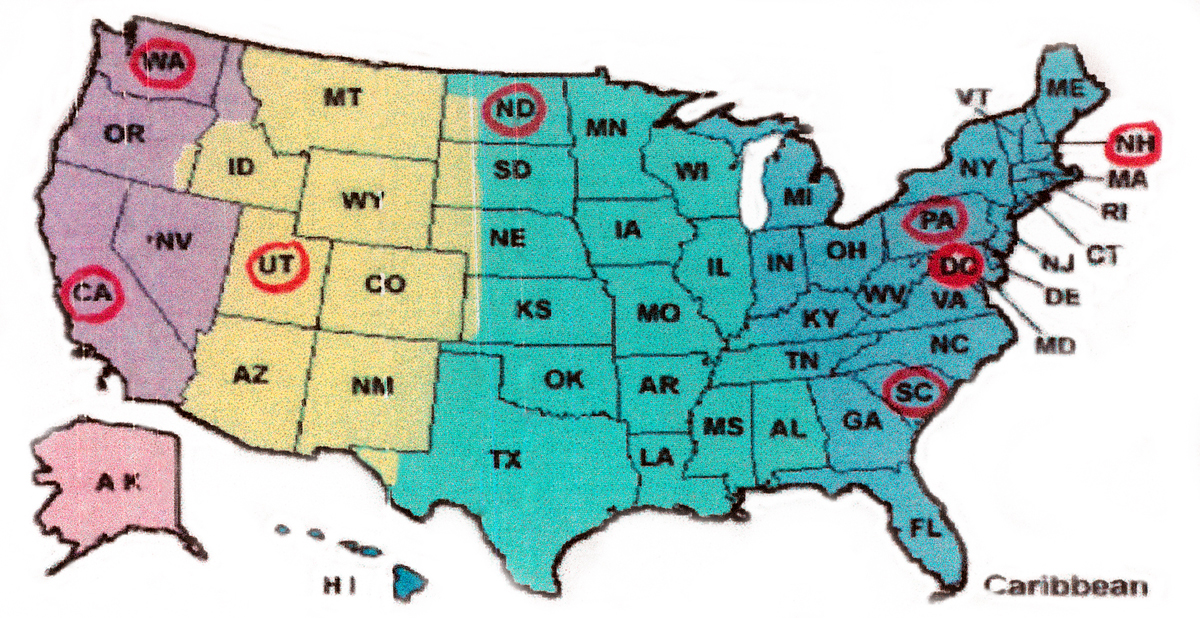

Smith had also set his sights on national expansion. He had an idea of a “Council of MEDEX Programs”—a program in each time zone. The idea was to build the program’s reputation and coverage by engaging influential medical academic supporters in key communities across the US.

He gained the interest of Bella Strauss, a physician at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. Also in his sights was Dr. Bob Eelkema at the University of North Dakota, followed by Dr. Cleve Hudson from South Carolina and contacts in Utah.

Smith reached out to include his alma mater, Howard University. At first, he couldn’t talk them into it. “Essentially, I said I’m sitting on all this money,” he recounts. “The President of Howard was a friend of mine. He picked up the phone and called the Medical School Dean. We moved ahead.”

Next was outreach to the community in South Central LA. “The town meeting there was the most difficult we had,” says Smith. “Those black mommas kicked my ass! ‘What do you mean trying to sell us on second-class medicine? You ought to be ashamed of yourself.’”

Steve Turnipseed (Class 1) had accompanied Smith, and talked for 20 minutes about what he had accomplished as a Medex at Group Health Cooperative in Seattle. After hearing Steve, those at the LA town meeting said, “We want MEDEX!”

Smith’s plan for a “Council of MEDEX Programs” was to have representation across each time zone in the US.

Smith had pulled together a Council of MEDEX Programs—a tightly knit group of people across the nation who were interested in growing the program. They met mostly by phone.

Dr. Gerry Basset became instrumental in the expansion of MEDEX outside the Pacific Northwest. “About the time of the pending legislation, I left UW and went to North Dakota to become the Director of the University of North Dakota program, MEDEX Central,” he says. Dr. Bob Eelkema had approached Smith and Basset, expressing an interested in starting a program at the UND School of Medicine—Public Health. “We put together a staff with similar backgrounds,” says Bassett.

During that time Smith received a call informing him that the Senate Finance Committee had on its agenda a discussion to talk about reimbursement for PAs. He arranged a conference call among the MEDEX Council to get the topic off the agenda. “I thought it was too early,” he says. “If the Committee were to bring it up they’d kill it. It would have been dead for decades if that happened.”

Managing Imagery

Smith was keenly aware of all the careful steps required to manage social change. “My avocation is the field of communications,” he has said. “I know nothing about it, but I’m interested in it.”

In the case of MEDEX, he was introducing the first new medical profession in 100 years. And he knew enough to realize there were key steps to be taken all along the way with image in mind.

All of the MEDEX candidates fit a particular profile that one could conventionally describe as masculine and handsome. Additionally, the country was still in the middle of the Vietnam War, and there had been a lot of media coverage on the contributions of Army medics and Navy corpsmen.

Speaking to Ray Vath, Smith pitched a way to visually distinguish the Medex from the physician. The idea was to have them wear blue coats instead of the usual white medical coats. “I’ll tell them to wear polka dots if that’s what you want,” responded Vath.

Perhaps most important was the naming convention. An early MEDEX document explains the original intent for the terminology. “When the term appears in capital letters, reference is to the training program. The term in lower case letters (Medex) refers to the trainee or the graduate of MEDEX.”

Those who graduated from the MEDEX program could apply the credential Mx after their name. For Smith, this was an effective distinguishing mark to MD for the physician.

But this term was not to gain wide acceptance outside of Washington State.

Douglas Fenderson, a HRSA official, returned to DC with a glowing report of the MEDEX program, forecasting that the new profession was going to grow. He asked Smith to send him a couple of Medex’s to move things forward. “That’s impossible,” Smith told him. “These guys have docs who have agreed to hire them. We can’t renege on our promise.”

Smith suggested that Fenderson contact Dr. Bob Howard, the former director of the Duke University PA Program. There he found two Duke graduates that were subsequently hired by HRSA. Duke’s early naming convention was physician associate, which later became physician assistant. The abbreviation PA stuck and trumped MX. “I decided I wasn’t going to pursue the imagery issue,” says Smith.

In the interests of a different sort of imagery, Smith moved the MEDEX offices out of the UW School of Medicine and into the same building as the Washington State Medical Association. “That way we had the same address as the WSMA,” says Smith.

Before long, major media were knocking on Dr. Smith’s door. NBC News correspondent Don Oliver called saying, “We’ve heard about this program called MEDEX. We’re coming up to do a story.”

“Are you asking me or telling me?” replied Smith. “First, I didn’t trust them and, second, it was too early. We were still trying to gain acceptance.”

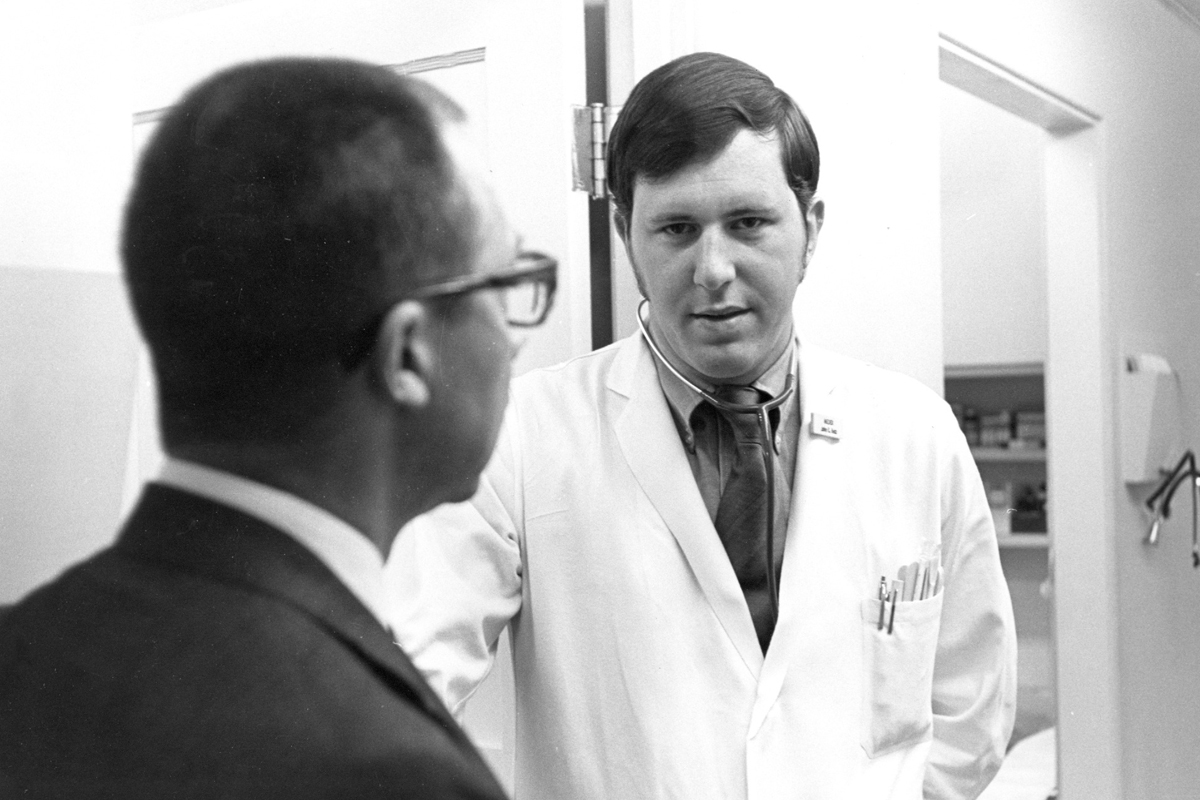

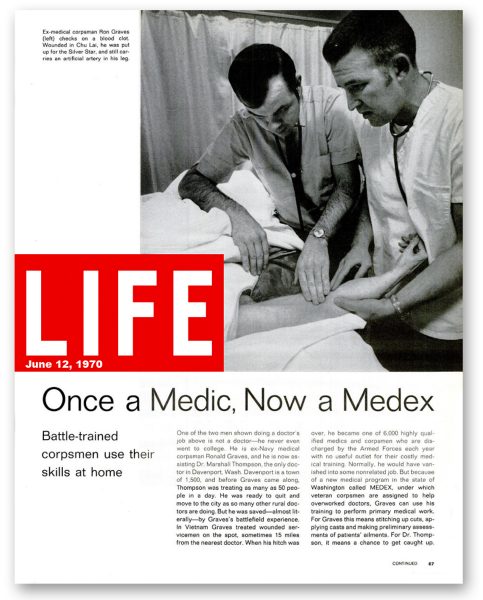

By the time the Class 1 students were placed with their preceptor physicians, the media could not be held back. In 1970, lengthy stories about MEDEX appeared on the NBC and CBS Evening News. Soon, feature stories in Parade, Time and Life Magazine followed. The news angle was this: here is a solution to the crisis in healthcare facing our rural communities. All the coverage was exceptionally positive and receptive.

Pioneer vs. Settler

Dr. Richard Smith devoted 4 years of his life to the development and launch of MEDEX Northwest, from 1968 to 1972. In that brief time he brought forth a new medical profession to address a worsening healthcare crisis—a shortage of practitioners, particularly in rural environments. He also tapped into an underused resource, that of our medically trained returning military veterans.

“It wasn’t simply a matter of training some people and sending them out into new jobs,” he says. “Transformation is a systems metaphor for change. It’s more process oriented and dynamic.”

Through MEDEX and the emerging PA profession, Smith and his colleagues got into all types of communities—affluent, poor and middle-class. “That’s when I knew we had a success on our hands,” he says.

And it was at that point that Smith knew he had to leave. “Because I’m not a settler,” he says.

Actually, this was a quality shared by all of the leadership of MEDEX at the time. Speaking of Smith, Deputy Director Gerry Bassett, Bill Freeman and himself, Ray Vath says, “All of us were innovators. We love the challenge of creating, but not one of us likes to manage.”

That’s the difference between a pioneer and a settler. Smith knew himself well enough to recognize that his talents were best applied to systems development.

David Lawrence succeeded Smith as the Director of MEDEX from 1973 to 1977. He went on to become the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Kaiser Foundation Health Plan.

David Lawrence was a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar at the University of Washington, and he was recruited to replace Smith as the Director of MEDEX from 1973 to 1977.

And yet there was much more innovation to come from Dr. Richard A. Smith. Ever a man of vision, he wanted to take the concept of the MEDEX program global. In many ways this would bring him full circle, back to his time with the Methodist missionary in 1951 Cuba. The dream was to train mid-level healthcare workers in countries where there may not even be a medical school or a national health ministry. MEDEX International would become the focus of his work for the next 10 years, from 1973 to 1983.

Next: Dr. Richard Smith, Part 2—MEDEX International

† “Medicare and Medicaid at 50: America’s Entitlement Programs in the Age of Affordable Care” (2015) by Cohen, Colby, Wailoo and Zelizer