Simon Mendoza – MEDEX Seattle Class 48

When he was a child living in Royal City, WA, Simon Mendoza’s family would travel 25 miles to a medical clinic in Othello for health services. Now a student in his clinical year with MEDEX Northwest, Simon has been placed in that same clinic—the Columbia Basin Health Association Othello Family Clinic—for his 4-month family medicine preceptorship.

“I feel at home here with the people, the community, and the patients I’ve seen,” he tells us. “Some of the patients here have been my classmates from middle school, some of my teachers, friends. It’s the great rural small community experience that I’ve always wanted.”

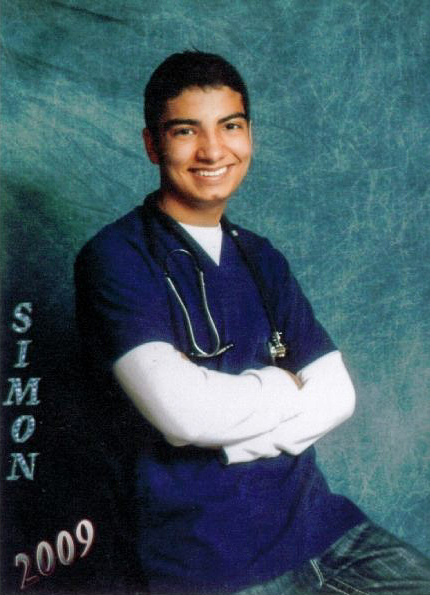

At 24, Simon is the youngest in his class of MEDEX Seattle 48, and across all four sites. The median age for students entering the University of Washington physician assistant training program is 33, representing a second or third career path for most. “I tend to be a little mature for my age,” Simon says. “I really enjoy having older classmates. I felt comfortable with them. I like the maturity that MEDEX brings.”

But age belies Simon’s experience. At 16 he became a Certified Nurse Assistant through a program offered at his Kent, WA high school. This trained him to perform some basic nursing tasks like taking vital signs, making beds and changing bedpans. But nothing could have prepared him for what was to come, except for his innate abilities as a healer.

As soon as he finished the CNA program in his junior year, Simon volunteered with the Red Cross and went to Houma, Louisiana in the aftermath of Hurricane Gustav.

“I had just turned 17, and I was one of the youngest medical services volunteers they ever had,” he explains. Upon arrival in Houma, he was put solely in charge of an entire shelter with over 230 people. It was two weeks before some registered nurses arrived to relieve him.

“I learned pretty quickly,” he says. “Just being there for people at their lowest point really made an impact in my life.”

Simon explains that the central headquarters for medical services was in Baton Rouge, 85 miles from the shelter. “I could consult with them by phone, but it was a couple of hours drive from headquarters,” he says.

Two elderly women recovering at the FEMA shelter in Houma, LA in the aftermath of Hurricane Gustav. Photo copyright Matt Stamey

At the shelter Simon was called on to treat a few acute injuries, but most medical issues were chronic conditions. “We had a lot of people who were diabetic, who didn’t have their insulin,” he says.” Conditions at the shelter were challenging, as there was no electricity. “Some people were bedridden, and we had a couple of people who had heart attacks. I couldn’t do much for them besides give aspirin and call 9-1-1.” But under the emergency conditions in the aftermath of Gustav, the 9-1-1 service was backed up. “It took them close to 30 minutes to arrive.”

We wondered how the then 17-year-old Simon managed to maintain his composure under these extreme circumstances. “I’ve noticed that if I remain calm people remain calm,” he tells us. “I feel like I matured at a very young age, which is part of the reason I was able to remain calm in that situation.”

A sheriff’s officer helps a woman at a shelter after Hurricane Gustav. Photo copyright Matt Stamey

To pay for his education, Simon has been working full-time since the age of 16. Even now, while in the MEDEX PA program, he works as a telemedicine triage coordinator on the weekends.

In high school Simon was in the Running Start program, which allowed him to simultaneously work towards his high school diploma and college bachelors’ degree. Now in a 2-year masters’ program at the University of Washington, his access to higher education is possible under DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program established by the Federal government on November 20, 2014. This is crucial because Simon is not a US citizen, even though his immigrant parents brought him here at the age of six months.

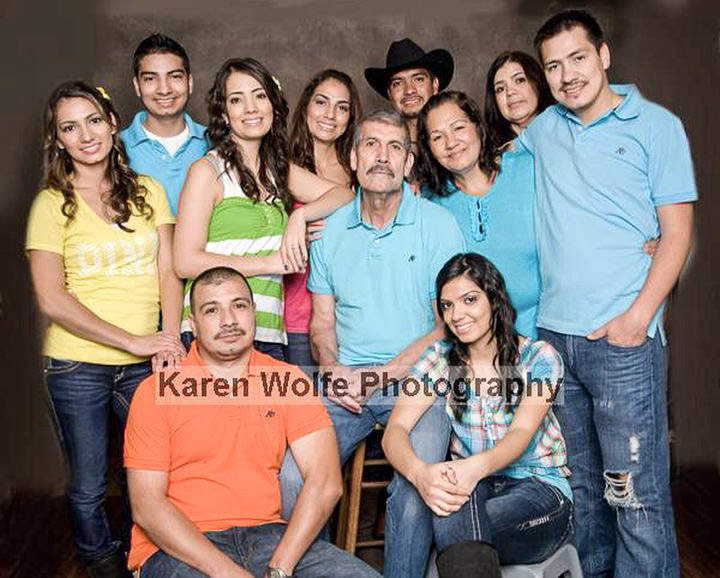

Facing a tough economy in Michoacán, Mexico, Simon’s parents immigrated to Washington State. “My uncle was already in the United States and became a resident after President Reagan passed the Immigration and Reform Act in 1986,” Simon says. “He was in contact with my father back in Mexico, and encouraged him to come north to build a better life for us. That’s exactly what my father did.”

Within months, Simon’s mother and the nine children followed. Simon was among the youngest of the siblings. They all settled in Grandview, WA, sharing housing with their uncle’s family. “He also had nine children,” says Simon. “We all lived in one place for quite a while.” His father and uncle worked in the fields and orchards of Grandview as farm laborers, picking apples, asparagus, peaches and cherries. In time, Simon’s father was offered a good position an hour from Grandview at Smith Brothers Farms in Royal City, WA. The senior Mendoza worked there for several years until the accident.

“His arm was crushed in a manure strainer,” Simon recounts. The machinery broke his father’s arm, and mixed the manure in with his blood. “It was pretty much septic. They nearly amputated his arm, but the surgeon was able to save it, thankfully.”

It was his father’s near-death accident that first inspired the 8-year-old Simon think about medicine.

Simon’s elder siblings had settled just south of Seattle in Kent, WA. With the father unable to work the farms, the entire family relocated to Kent where they remained.

By middle school, Simon developed a sense that he was undocumented and that there was a danger of deportation. At that time there were immigration raids in Eastern Washington, in the very town where the family had lived. “You would hear about it on the radio,” he says. “It was slightly terrifying to me. I began asking questions, and that’s when I learned what I was.”

The US was the only country that Simon had ever known, so all this added an element of uncertainty to his future. Throughout his early schooling Simon received considerable support from his teachers and counselors. “They saw my ambition and drive, but they didn’t know the whole story,” he says. “I didn’t tell any of them I was undocumented until high school.”

The conversation returns to Simon’s 21 days as a high school age volunteer CNA in the aftermath of Hurricane Gustav. He considers this as another formative event along his path to pursuing a medical career. “After that experience I was 110% sure that I wanted more responsibility,” he tells us. “I wanted to further my education because I knew I wanted to help people.” But he wasn’t sure of the best possible path—physician, nurse, or physician assistant. In the Louisiana shelter he met a PA for the first time, and was impressed.

“The way he worked to help these people was amazing,” Simon recalls. “His father was a community pharmacist, so he worked day in and day out to get these people their medications. At that time I don’t think PAs had as much of a prescriptive authority. But his drive to help the people, his capabilities, his knowledge—he was incredibly smart.”

After the Louisiana experience, Simon returned to Kent. There was another year and a half of high school while concurrently attending college courses towards his bachelors’ degree under Running Start. All along he continued to volunteer locally as a CNA with the Red Cross. He gained further experience during his final year of study at UW by volunteering for a free clinic in Auburn, WA, followed by two years of employment with a Woodinville physician.

All this pushed Simon to meet his 4,000 hours of patient contact required by MEDEX at that time. In 2013, with a degree in microbiology under his belt, he took steps to apply to the UW physician assistants program. But there was a potential obstacle: Simon was undocumented.

By that time President Obama had put in place the DREAM Act, which provided some shelter for the undocumented children of immigrants under the age of 31. Short for Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors, the DREAM Act is a legislative proposal for undocumented immigrants in the United States that would first grant conditional residency and, upon meeting further qualifications, permanent residency. There are a lot of unknowns and no guarantees.

Soon after passage of the Act in June of 2012, Simon applied. “It took me a couple of months to put together my paper work,” he tells us. Acceptance under the Act granted him a two-year renewable work permit as well as a social security number.

Still, there was a problem. “A lot of graduate schools required permanent resident status in order to apply, and I didn’t have that status,” he says. The MEDEX physician assistant program in Seattle is a masters level program. Operating under UW Medicine, MEDEX is subject to the same constraints as the university. And UW had never accepted an undocumented student into any graduate program without permanent residence status. “The medical school just said that I couldn’t apply with my DACA status.”

Still, there was a problem. “A lot of graduate schools required permanent resident status in order to apply, and I didn’t have that status,” he says. The MEDEX physician assistant program in Seattle is a masters level program. Operating under UW Medicine, MEDEX is subject to the same constraints as the university. And UW had never accepted an undocumented student into any graduate program without permanent residence status. “The medical school just said that I couldn’t apply with my DACA status.”

Uncertain of how this would work, Simon sent an email to the MEDEX admissions team. “Their main concern was my ability to work afterwards— to obtain national certification and a license from the State of Washington,” he says. That’s when Mariah Kindle, Director of Admissions at MEDEX, stepped in to research the issue.

“She was great,” says Simon. “Just very supportive, saying that she would look into everything, contact the MEDEX leadership as well as leadership at the University of Washington and see what the legality of my situation will be and how it will effect applying to the MEDEX program. She made the whole process not easy but easier.”

Mariah Kindle adds some insight into the process of admitting Simon Mendoza to MEDEX.

“Simon’s story is interesting,” Mariah says. “He came to the United States as a young child. Based on conversations around his life, academic, and clinical experiences, he was clearly a mission fit. Before MEDEX admitted Simon to the program we spoke to him for a very long time, about nine months prior to him submitting an application. Turns out he was an excellent applicant. He had an undergraduate degree here at the UW with a very high GPA. He’s really our first Deferred Action Status Student.”

When Mariah first started talking with Simon about his path, she met with members of the MEDEX leadership group to determine what his process would be. “That was after a lot of research I had done,” she tells us. Mariah checked with the State of Washington to understand the rules for DACA students. She spoke to the University of Washington concerning policies for financial aid and qualifications for masters’ programs. She reached out to NCCPA—the PANCE national certification body—to make sure that even after Simon finished the program that can he sit for the board exam. She contacted MQAC, the Medical Quality Assurance Commission, which licenses MEDEX.

“Turns out the rules applied the same for Simon,” she tells us. “Students with deferred action status must have a Social Security number, pass an accredited training program, sit for the national certifying exam, and they can practice in the State of Washington.”

With all that the MEDEX leadership group decided that Simon had to follow all the same steps as every other applicant to the program. Mariah clarifies that “there was no blanket policy actually. It was decided that MEDEX would look at each person with DACA status individually to be sure they not only meet the standard MEDEX qualifications, but also that they are a mission fit. Simon was just kind of the perfect candidate for MEDEX. He’s the whole package.”

At that time the UW did not accept students with DACA status. “But because of the MEDEX experience with Simon, the UW School of Medicine looked at our process and took the same approach—looking at people individually, making sure they qualify on the same level as everybody else,” says Mariah. “I think that’s the key.”

On September 30, 2014, the UW School of Medicine announced a change in policy regarding DACA applicants in a Seattle Times story. It read, in part, “The University of Washington’s School of Medicine has joined at least 35 others that now admit students who were born outside the U.S. and brought into this country illegally.”

Deferred Action Status Students cannot receive State or Federal monies. In fact, this is one of the largest hurdles that students with DACA status face.

With his path to the admission process cleared, Simon began gathering the necessary documents for MEDEX. “I’m still considered undocumented even though I have DACA status because it’s only a temporary deferral,” he says. “It’s not like I have permanent status at all. I have to reapply every two years. There is a $465 fee and they grant you the two-year work permit every two years.”

Still, much remains uncertain for the future. Given the current volatility of the US body politic—with a strong anti-immigrant rhetoric—there is reason to be concerned. “If Romney would have become president in 2012, he would have immediately ended the DACA program and deported us all.”

“Most people have no idea what all this means,” he says. “Some people ask me, ‘Why don’t you just apply to be a citizen?’ If it were that simple we’d all do that.”

He’d get in line if he could find an end to the line.

What puzzling is that Simon’s parents became permanent residents in 2013. “They brought me to this country,” he explains. “All of us were undocumented. They were undocumented, but they applied for a visa with my uncle’s sponsorship because he was a US citizen at the time. We waited in that line for over 20 years. When our visa number became current I had already turned 21. So I was no longer eligible to become a citizen under them. They became residents, and then I was sort of left out. To me it makes no sense.”

MEDEX students deal with the stress of a greatly compressed learning schedule in their didactic year, and a sequence of ever changing monthly rotations in their clinical year. Add to that the complications of two years of lost income, endless studying, and the impact of all this on their relationships. Simon’s undocumented status adds a whole other layer of stress. How does he manage the uncertainty?

Again, what strikes those who meet Simon is the calm he brings to challenging situations.

“I try to take it one day at a time,” he says. “I don’t worry about several years ahead. I just look at it one day at a time. What can I do to better my situation and take the next step forward?” Simon is part of the Latino Medical Students Association and the National Hispanic Medical Association. “We are advocates for immigrant, undocumented students to get a higher education.” And by incrementally moving the ball forward, Simon opened up possibilities for other undocumented immigrants to higher education.

When we caught up with Simon during his preceptorship at CBHA Othello Family Clinic, it’s clear that he is in his element. Migrant farm workers are the principle focus of the clinic. In fact, the mission statement of the clinic is “Keeping healthy those who feed the world.”

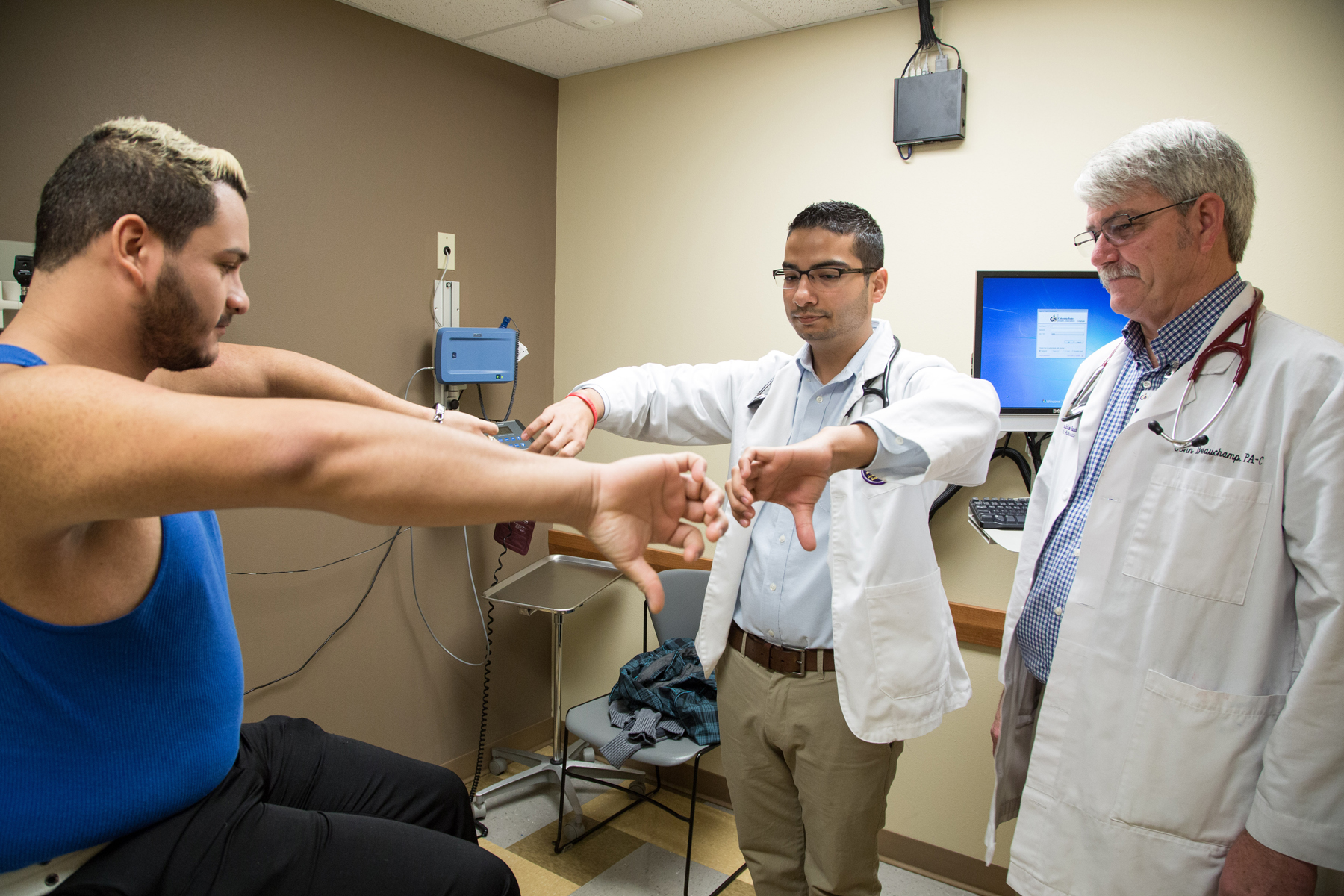

Simon Mendoza during his family medicine preceptorship at Othello Family Clinic with John Beauchamp, PA-C.

“We pride ourselves on serving agriculture and migrant farm workers, and we don’t discriminate against people who can’t afford health care,” Simon says. “We try to serve everybody without regards to ability to pay, no insurance, race, age or anything. That’s the great thing about CBHA.”

“Patients remind me of my parents,” he tells us. “Cultural competence is necessary to provide great care to this community. This includes an understanding of traditional healing practices commonly referred to as curanderismo. Herbs for example, are commonly used to treat anything from insomnia to constipation. Understanding this and asking about it is very important because there may be serious interactions with certain prescription drugs.”

It’s clear that Simon is in his element here in rural Eastern Washington. “I would love to come back and work in a town like Othello. I love the closeness of the interaction with patients,” he says. “My passion is for prevention and management of chronic diseases and mental health disorders.”

Simon’s 4-month preceptorship at Othello Family Clinic concludes at the end of January. After that, his clinical year consists of six 1-month rotations, most likely in the urban Seattle area. Emergency medicine is next. “Yeah, most of the specialties are over there,” he says. “Even here we have to send patients to Tri-Cities for specialty care. And I don’t mind that. I’ll get a lot of exposure to complex patients over on the west side, especially associated with University of Washington. I’ll get a lot of great exposure, then bring it back here. So I’m looking forward to that.”

Simon has already inquired with the CBHA leadership about returning to the Othello Family Clinic once he graduates from MEDEX and obtains his national certification as a PA. “I’m certain I want to end up here,” he says. “I love it.”