It’s the summer of 2010. I am 12 years old, glued to a TV screen. My mother silently enters the room carrying the largest plate our family owns, adorned with a vibrant array of fruit slices. She sets down succulent wedges of oranges, slices of apples with the skin carefully removed and cubes of meticulously diced melons. As children, it’s easy to take a mother’s devotion for granted, and I was no exception. If I could press rewind and watch that time of my life again, I’d watch my mother, doling out her love in the lifting of a knife to the flesh of fruit.

Growing up, plants never interested me, but I found an obsession with fruits. I liked that citrus came in segments perfect for sharing, and that green apples tasted better than red ones. I wondered, why are there so many fruits? Why are some sweet and some sour, some dry and others juicy, and some healthy and others deadly? Once you’ve seen a plant and gathered how it works, the plant-paradigm can be applied to most other plants. Get sun, make sugars, grow happily. Almost all plants play by these rules. But there’s no clear and common goal when comparing apples and oranges, tomatoes and coconuts, strawberries and plums. Fruits have their own agenda and the uniqueness of each fruit illustrates their ingenuity in the vivid world of plant biology.

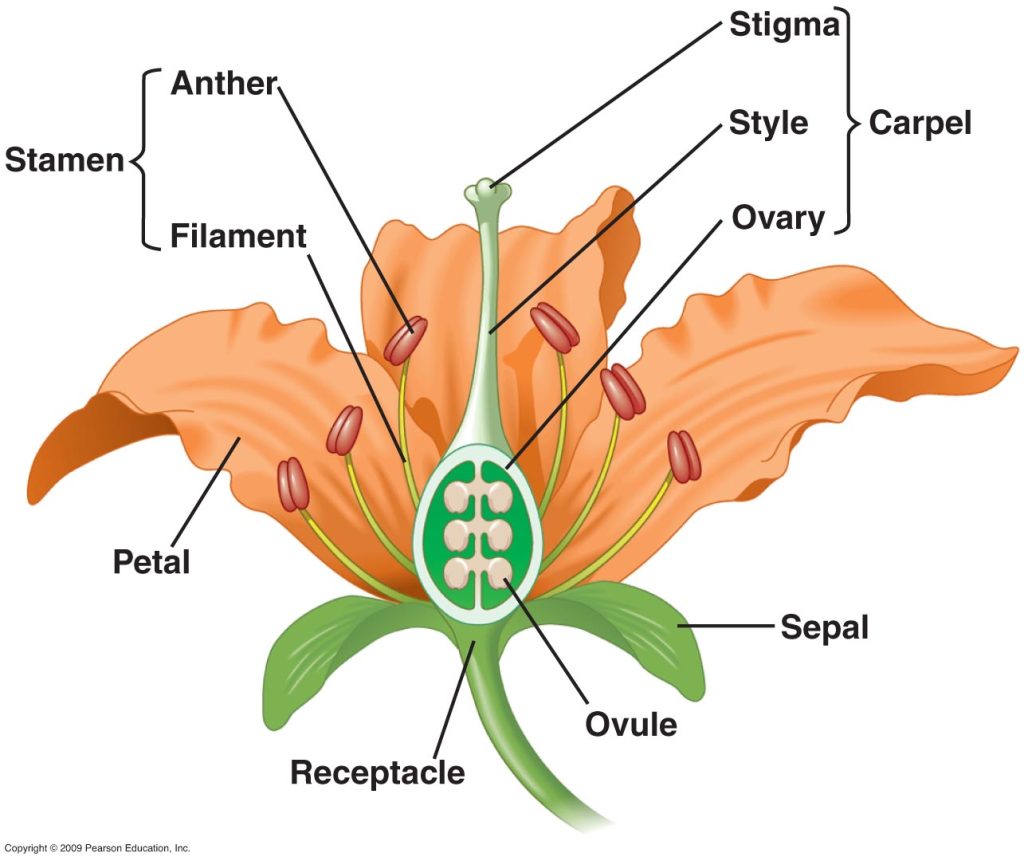

Fruits are special because plants didn’t always make fruit. In the past, they much preferred cones, and spores, and the primordial reliability of clonal propagation (I mean, why mate when you can make another you?). But a fruit? A fruit is the product of a love story. The wind that spreads male pine pollen to its female cone is indifferent and distant. But a flower entices, with the vibrant promises of reward for a job well done. A dutiful bee collects nectar for her queen, and unknowingly plays a role in a Romeo-Juliet romance. She carries love letters of pollen to a hopelessly romantic pistil, and the stigma of the flower sits patiently to receive its gift. A single grain of pollen holds a babushka doll arrangement of a reproductive cell within a vegetative cell. The speck of pollen begins extending a tube down the style of the pistil. This tube is an elongation of the vegetative cell, a free ride for the reproductive cell, and a one-way trip to fertilization.

The reproductive cell travels down the pollen tube and divides to form two sperm nuclei. One goes onward, to holy matrimony with an awaiting egg cell (n+n), but the other merges with two polar nuclei in the ovary (n+n+n), forming a triploid tissue known as the endosperm. Endosperm is baby food. It provides nutrients for the newly-made embryo developing in the ovary of the flower. There are endosperms all around us that we know and love. Coconut meat and water are the solid and liquid endosperms of a coconut seed. A kernel of corn is mainly endosperm, and the flour that becomes our bread is mostly the milled endosperm of a wheat grain. When a seed germinates, its surface area can expand many times past its original size before the plant ever begins photosynthesis. This rapid growth is fueled by the nutrient-rich endosperm. The fertilized egg will grow to be the seed of the plant, and, as loving mothers do, the flowering plant will redirect energy and resources to the emerging fruit that encases the developing seed.

There still stands the question of why fruits develop. A flowering plant diverts substantial sums of sugars and metabolites to a maturing fruit that it will never taste or eat. Fruits are vessels. For the seed that they carry, they offer protection, food, and the chance at a better life elsewhere. In an evolutionary gambit, many of the fruits we love aim to allure. A wandering bear, a passing bird, ancient giant ground sloths all become unknowing envoys carrying seeds in their stomachs to spread elsewhere. By settling in distant lands, a plant species can colonize new niches, escape unfavorable environments, and reduce competition amongst relatives. Bearing fruit is a plant’s latest and greatest mechanism for propagating over long distances, relying mostly on animals instead of wind and water.

Within every fruit is a story to be told. A saga spanning generations that details an evolutionary struggle to disperse seed and survive in one’s niche. Species in the Citrus genus found their solution through prolific hybridization (interspecific mating), which allowed for incredible diversity within their clade. Pomelos and mandarins mingled to make oranges. Oranges partnered with their parental pomelos to make grapefruits. And grapefruits met with mandarins to make tangelos. And each and all are capable of coupling with each other to produce offspring carrying a resemblance to their parents. Through their diversity, they obtain the ability to thrive in a variety of environments, by taking the best traits of both parents.

My favorite story is that of the fig. As one of the earliest domesticated plants on Earth, humans and figs have grown alongside each other for millenia. And while that amount of time is difficult to fathom, figs have coevolved with aptly named fig wasps for tens of millions of years. A fig is special because its flowering is like no other plant. The tree develops the fig fruit first, which will hold hundreds of small flowers that require fertilization. Pollinating these flowers is an impossible mission. The fig ostiole (opening on the bottom) is incredibly narrow, and lined with pointed bracts that obstruct the tunnel. Only one insect is brave enough to venture through. A female fig wasp, looking for a home to house her young. She drags her way through the ostiole, losing her wings and antennae in the process and sealing her fate within this fig. She lays her eggs in this field of flowers while simultaneously pollinating them in order to prevent the fig tree from aborting this fruit. After securing the future of her offspring, she dies in a bed of flowers.

One doesn’t need to look at fig wasps to understand the selflessness of mothers. Like a coconut drifting across the ocean for a beach to grow on, my mother landed on the coasts of southern California to put down her roots. As a foreign tree on foreign soil, she stood tall, and raised my sisters and me on her own. The four of us spent late nights under a dim orange light, playing Rummikub and passing a plate of nature’s candy. We are the fruit she grew with love, fed with the flesh of oranges, apples, grapes, melons – fruit meant for sharing. We miss our mothers, and they miss us too. But we shouldn’t forget the nature of fruit. We were meant to be whisked away to strange soils to grow on our own, and mothers know this. They’ll rebel, urging us that we don’t have enough nutrients yet, and that we need more time to ripen on their vine. But we’ll drop from the branch all the same, and hope that the apple doesn’t grow too far from the tree.

William Albers is a 2nd year graduate student on the 5th floor of LSB, studying the molecular mechanisms that control flowering in Arabidopsis in the Imaizumi lab.

Wonderful writing, Will! Excited to see what else you do in your work moving forward.

Super Cool!