BEWARE FAKE TRADE NEWS: Outgoing European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström made a not-so-subtle swipe at Trump’s trade worldview as she countered some of the president’s most commonly held views during a speech Wednesday.

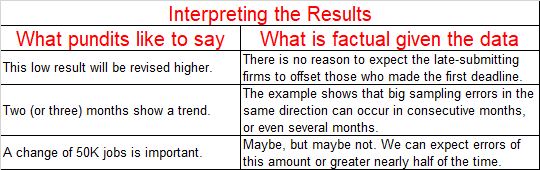

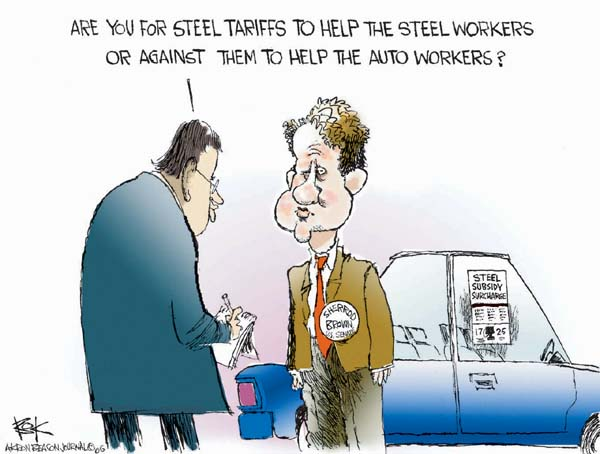

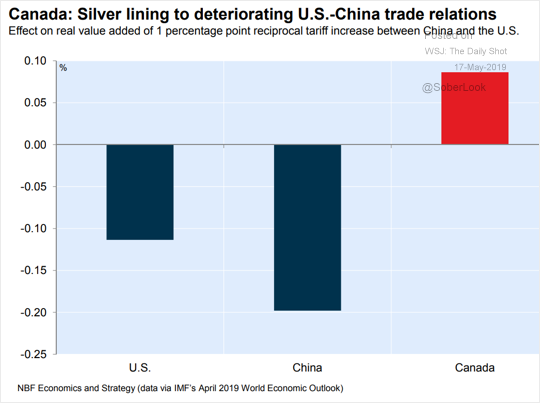

“The biggest misconception I have seen on the rise now is about tariffs,” she said. “People who advocate tariffs seem to base their arguments on two things: Tariffs target foreign business when they in fact the consumers. And tariffs are the tool of narrow interest seeking to protect industries at the expense of broader society.” Another wrong perception is believing that producing all goods at home is cheaper and better for the economy, she said, adding that this idea goes against the idea of comparative advantage.

Here is the whole speech

Ladies and gentlemen,

Today I want to discuss truth. In the age we live in – of instant communication, simplified messages and government by Twitter – truth can be difficult to hold on to. There is a quote, attributed to Mark Twain: “A lie travels around the globe while the truth is putting on its shoes.” It is a famous quote, and very apt – especially given that there is no evidence that he said it.

Today, many in this room will agree on most things – but we will disagree on others. And in my experience, it is always good to find a mutual point to start on.

So let me suggest one: Ladies and Gentlemen – the earth is round. Or to be accurate: an oblate spheroid. Life would be easier if it were flat:

- cartographers could make maps more easily

- lunar eclipses would not ruin our view of the moon

- all of the stars in the sky would be perfectly visible every night

But unfortunately it is not flat – a fact first proved in the 3rd century BCE, when Hellenistic astronomy calculated its shape and circumference. Since then, the evidence has mounted up. From astronomical calculations to simple observation. From ground-level views to photos from aircraft and spacecraft.

So why, despite all of this evidence, does the International Flat Earth Research Society maintain a membership? Why is there a small, but active, online community? Because they follow instincts over evidence. When they look around them, they see a flat earth.

I am afraid, however, that they are wrong. We sit here and we laugh about people believing the earth is flat, based on intuitive presumptions. Yet, these days many similar presumptions are made about trade – ones that feel intuitively true but are backed up by nothing of substance.

Often you hear people say that they are entitled to their opinion – That’s of course true, but even so, your beliefs should guide you, but not all decisions can be gut decisions. If you want to disagree with something, you have a responsibility to look at and understand the evidence.

This is something that has become very clear to me in my time as Commissioner for Trade. I am a proud liberal – I believe in open borders and free trade. My ideological beliefs have guided me – but sometimes I must recognise the reality of a situation that is constantly evolving, even where I have had some initial doubts.

So today I want to talk to you about a few things in trade – specifically: the things that feel intuitively true, but are in fact not, and what lessons we can draw from this for the future.

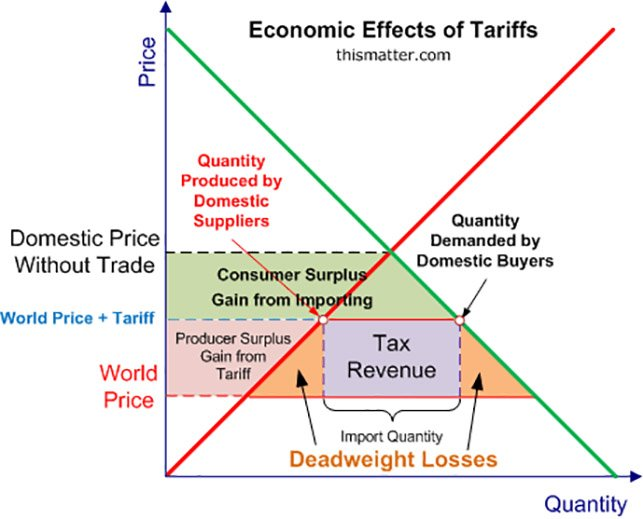

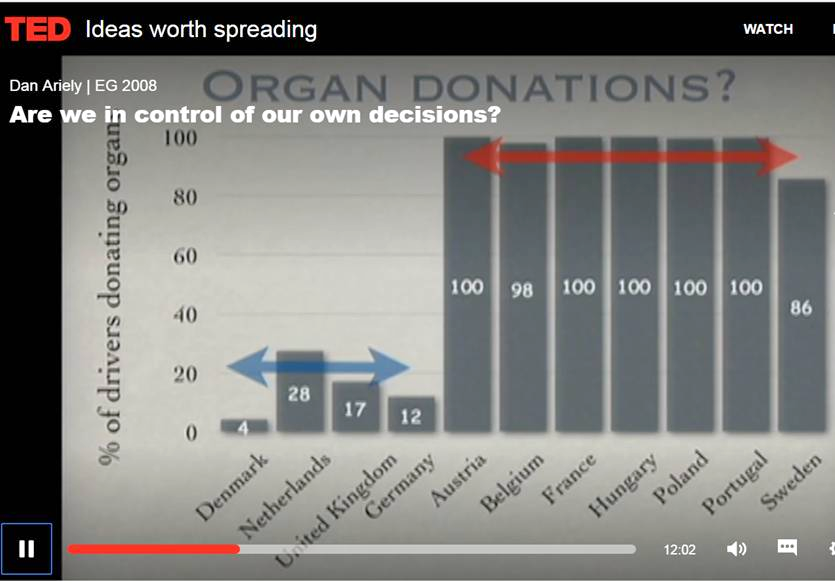

TARIFFS TARGET FOREIGNERS

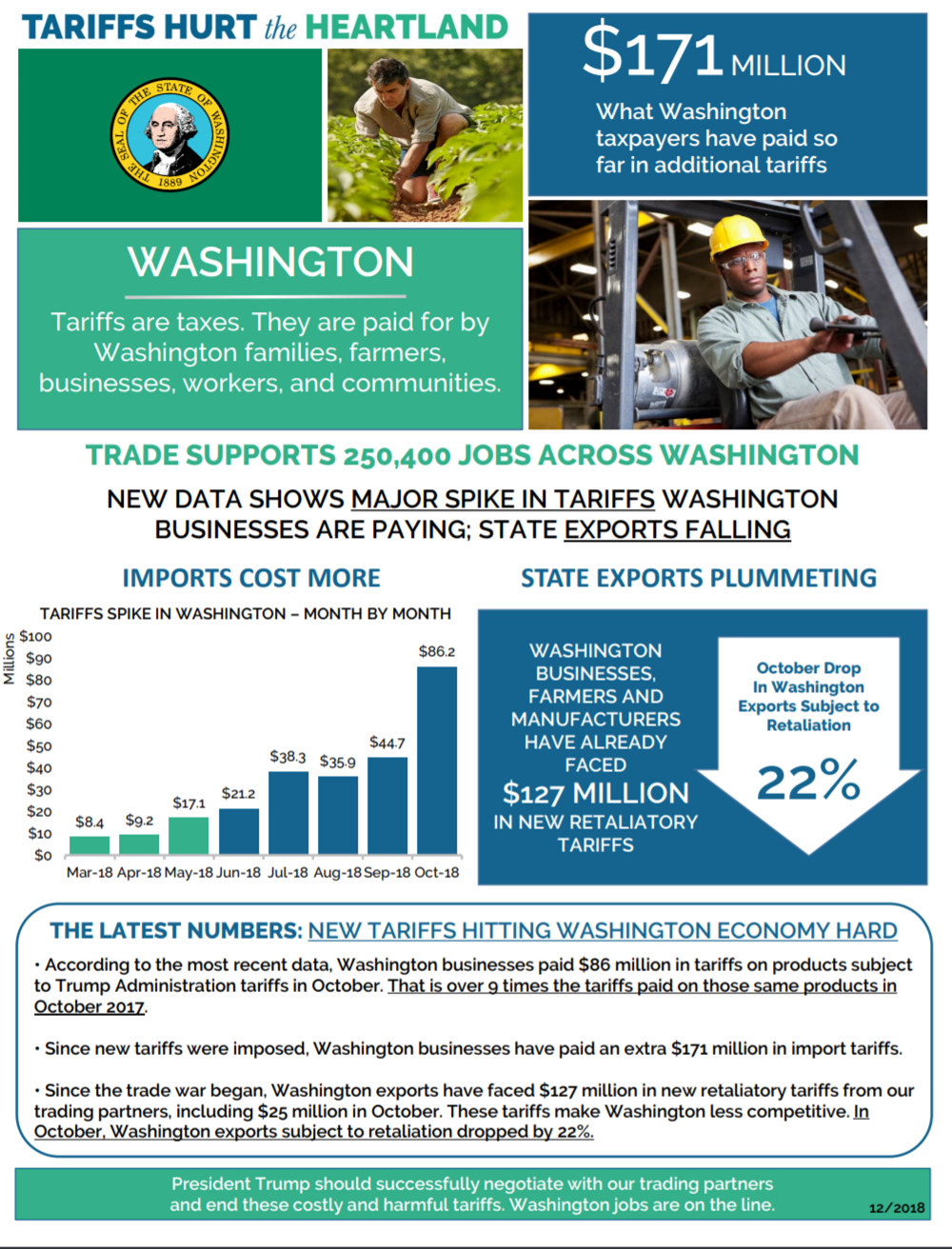

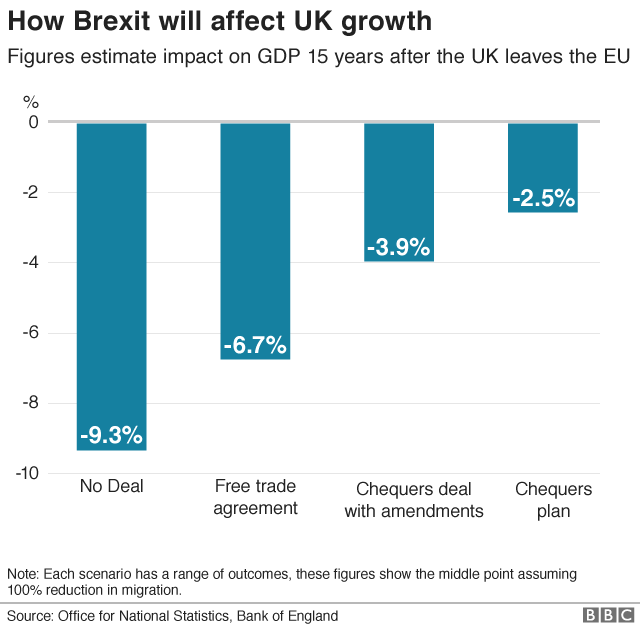

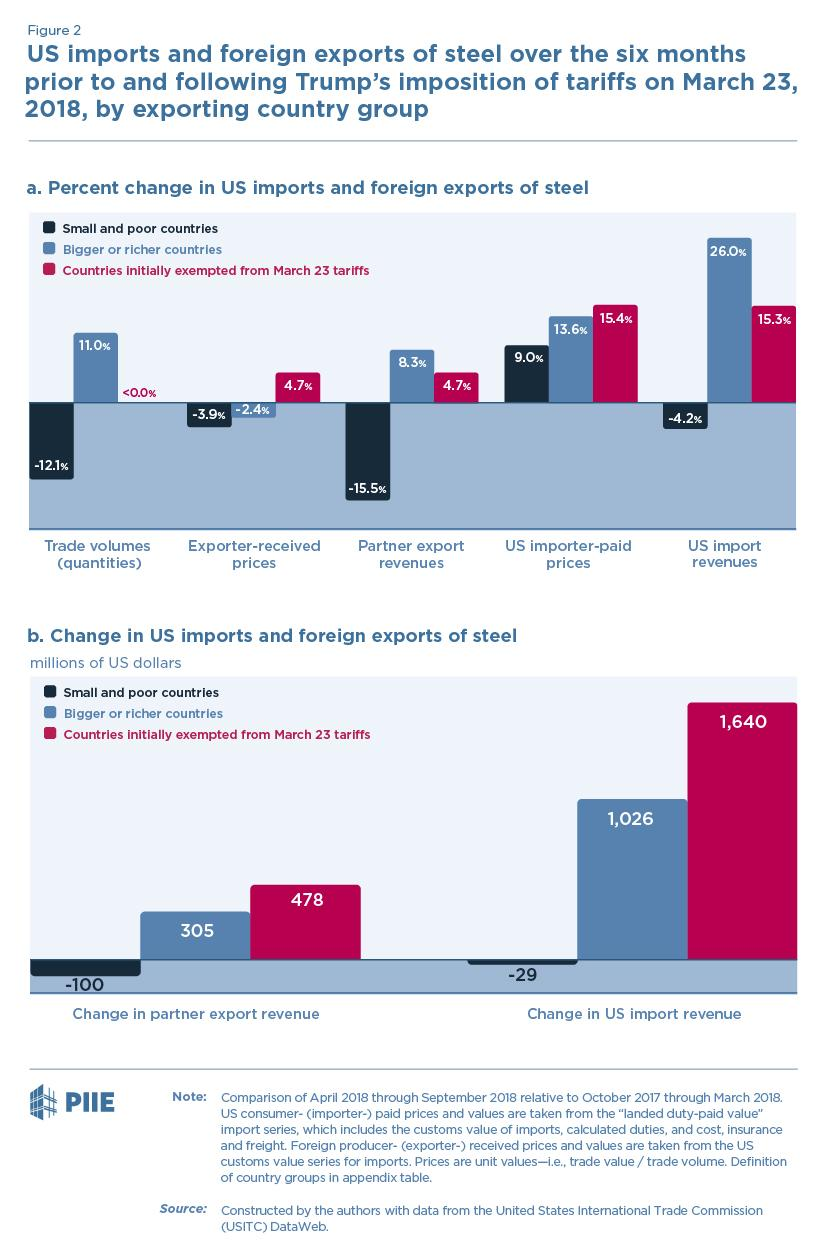

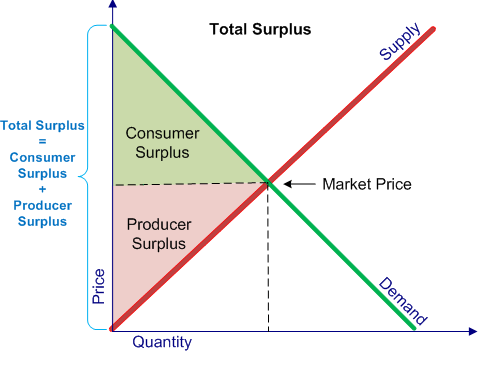

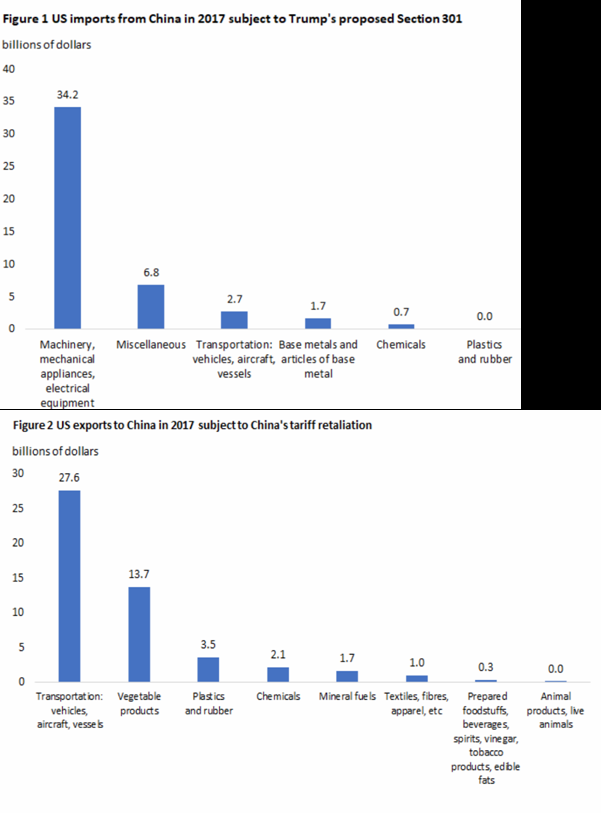

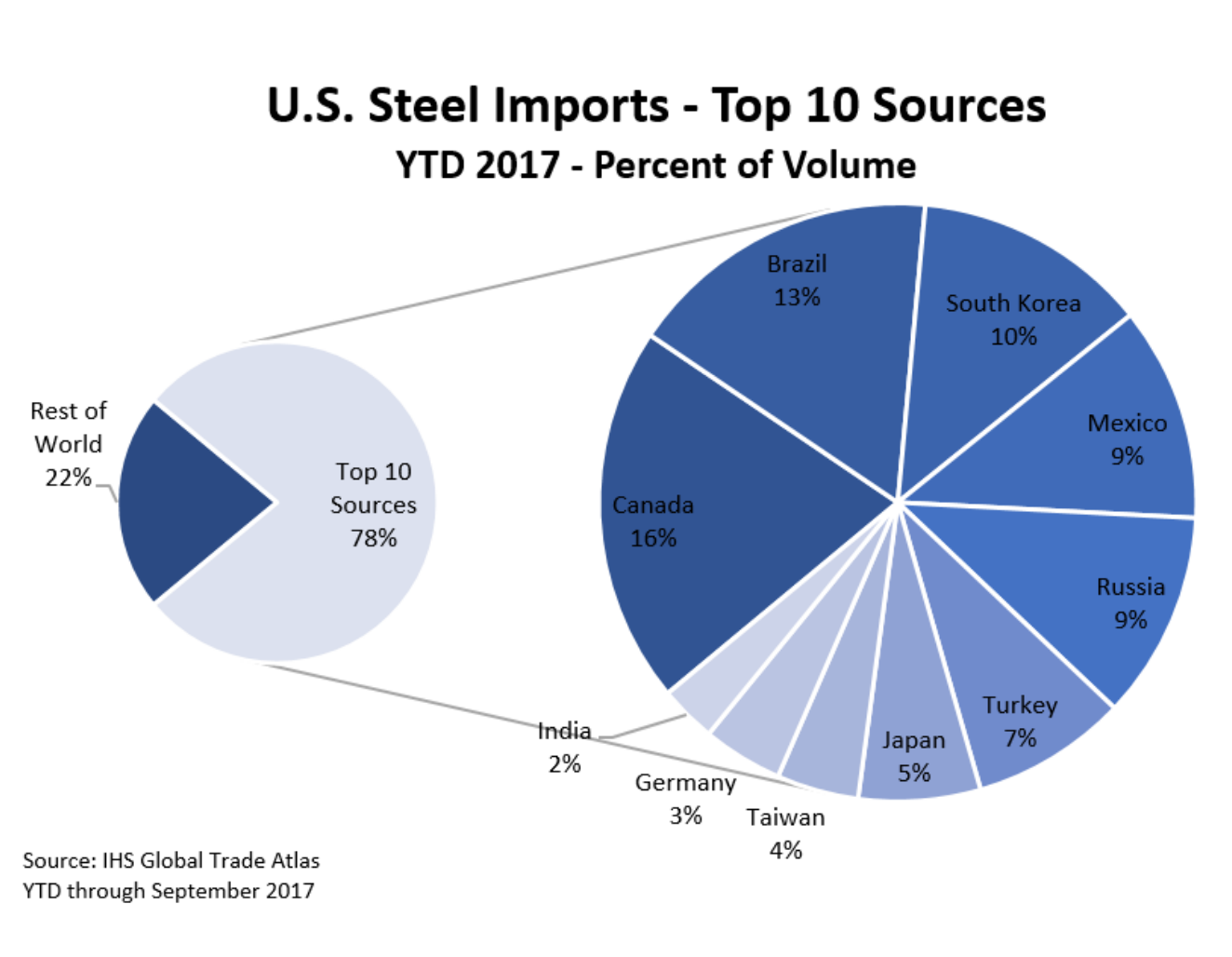

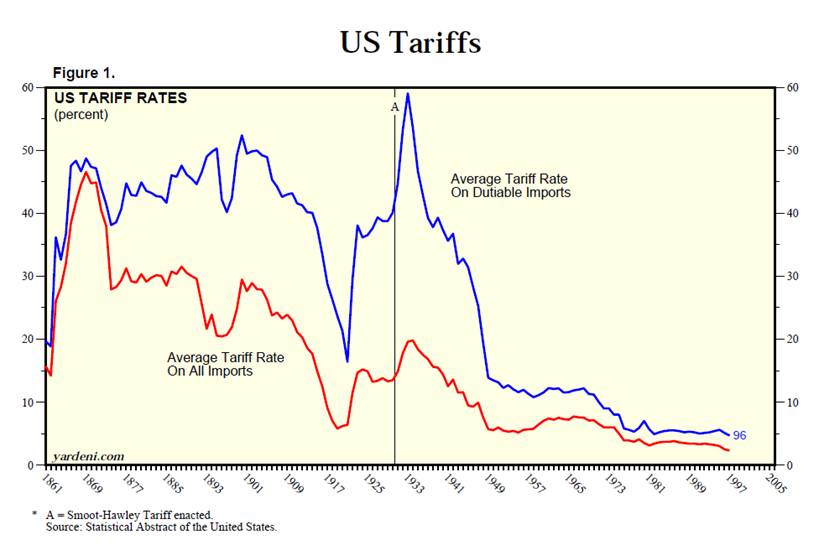

The biggest misconception I have seen on the rise is about tariffs. People who advocate for tariffs seem to base their argument on two things: The first is that tariffs target foreign businesses – when they in fact target the consumer. Tariffs are the tool of narrow interests seeking to protect industries at the expense of broader society.

The second is that if we make a product at home, we save money, strengthen the economy and create jobs. This is a tempting argument, but it is not true.

A basic principle of trade – that of comparative advantage, that specialisation is more efficient – seems to be increasingly forgotten these days. This type of thinking could lead to:

- unsustainable business models

- higher prices for ordinary citizens

- and a more fragile economy in the long run

Tariffs are not the answer to a transforming global economy – they are rarely the answer to anything – they are the equivalent of shooting yourself in the foot to hurt the shoe salesman.

EXPORTS ARE PROFITS

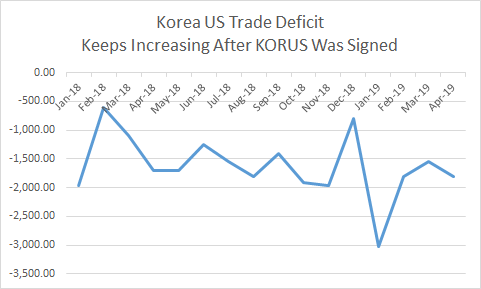

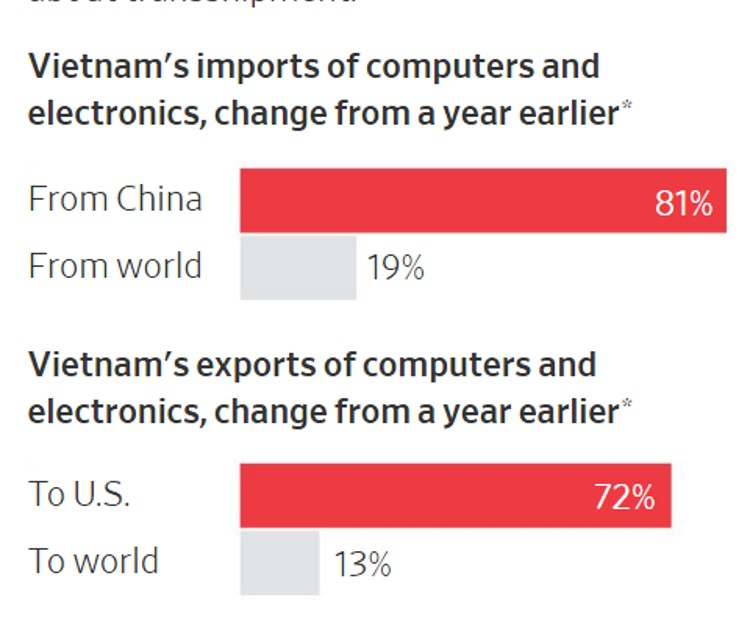

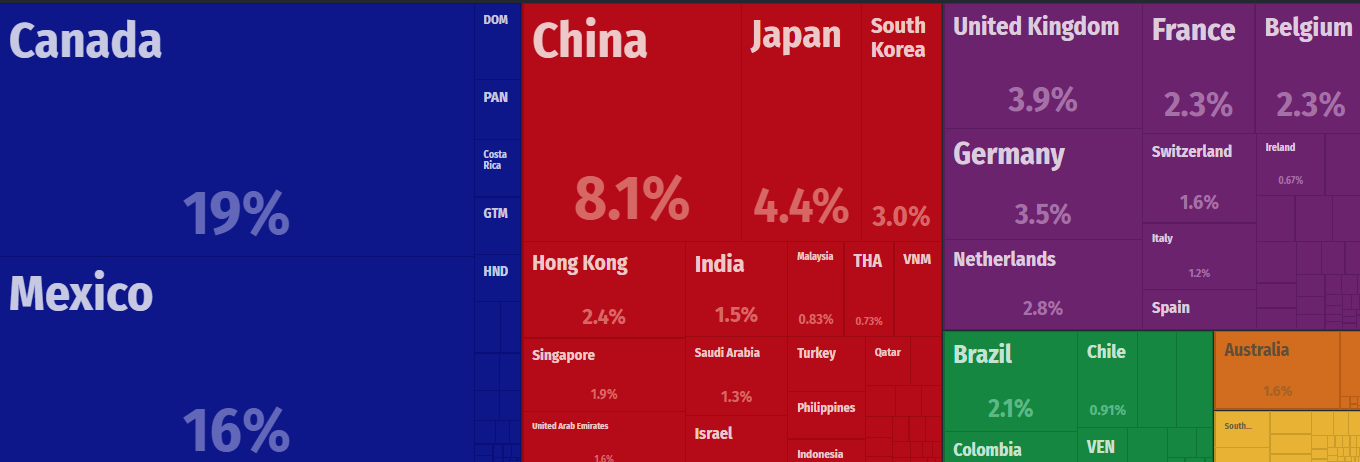

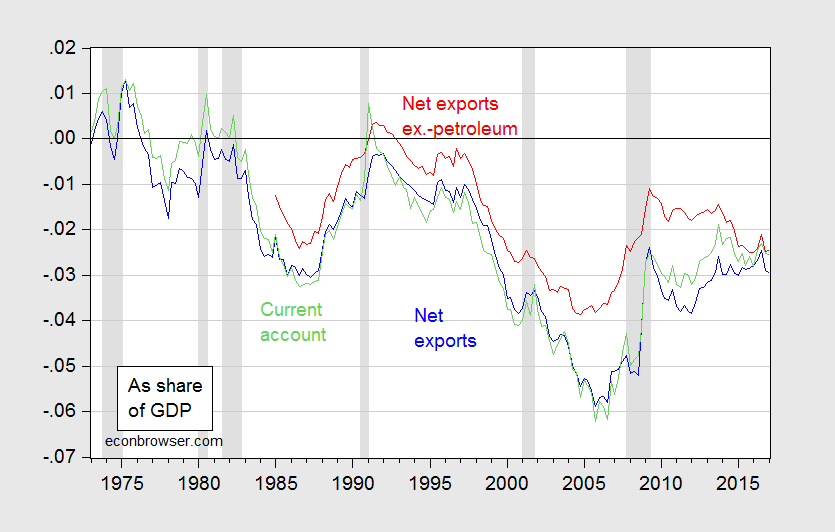

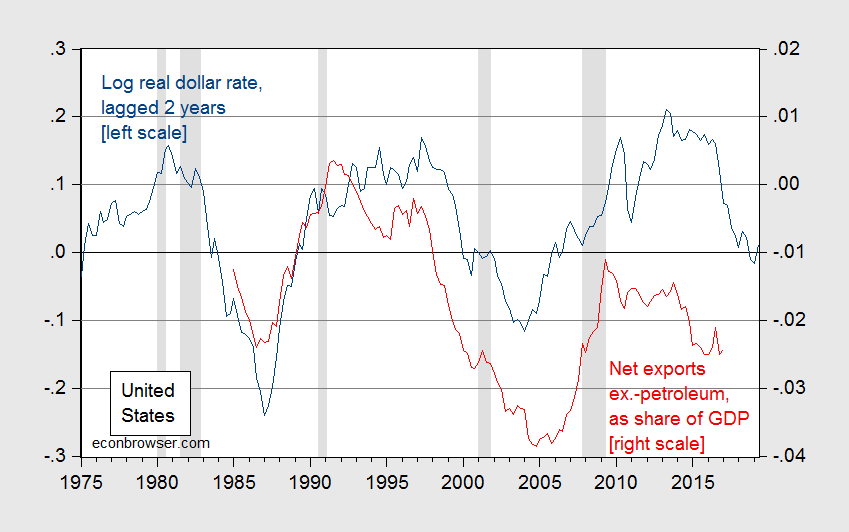

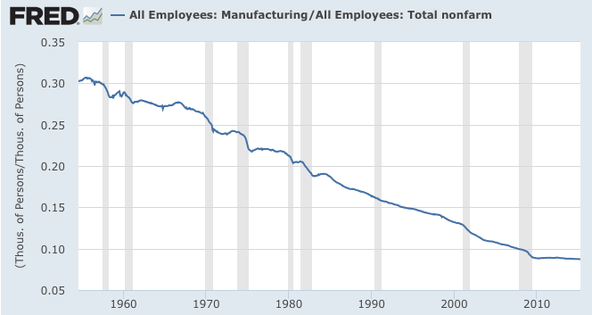

Another big mistake people make these days is confusing a trade balance with a bank balance. They misread “exports” to mean profits and “imports” to mean losses. This ignores a range of economic realities.

For example, the increasingly service-oriented economies in Europe, or the fact that getting hold of low priced and reliable imports is vital for our companies. Or that in a modern global economy, good will cross borders many times before they are finished – bringing prosperity and jobs wherever they go.

In fact, a surplus in trade can be a bad sign. It is a sign of weak domestic demand – this can make countries sensitive to changes in the global economy. Balancing the books on trade is not like a household budget.

TRADE IS ONLY FOR THE BIG GUYS

Another common misperception is that trade is only for big companies. But I know a few people who would disagree with that – Laura Fontan and Diego Cortizas, for example. They are the Spanish owners of Chula Fashion, a company based in Hanoi. They are a family-owned company with 68 employees. Our agreement with Vietnam will simplify rules of origin to make it easier to export to the EU.

Trade is important to companies, both big and small. However, it is true that small and medium-sized companies are underrepresented in global trade. Exporting can be hard. In a new market there are many barriers – customs, language, marketing. Throw tariffs and other trade barriers in and it becomes very difficult indeed.

Often larger companies can absorb these costs, but smaller companies might not be able to. This is why we have started to include provisions focusing on them in our trade agreements. These often include measures like:

- providing information online on market requirements

- an SME Helpdesk, where EU companies can protect themselves from unfair practices

- access to helpful contacts, like the Enterprise Europe Network

In the coming years, it is estimated that 90% of global growth will originate outside the EU. Developing and emerging markets will account for 60% of world GDP by 2030. Smaller companies are well placed to take advantage of that – taking up their role in global supply chains. Trade is not just for the big guys – it is an opportunity for all.

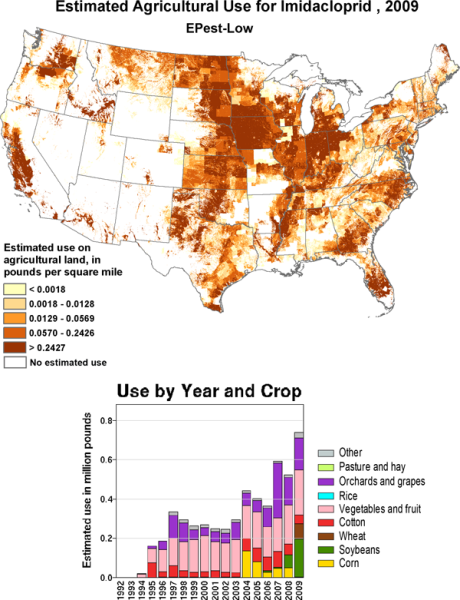

TRADE HARMS THE ENVIRONMENT

Another presumption is that trade is automatically bad for the environment. In fact, the picture is much more complicated than that. For example, it is better for the climate for northern Europeans to buy tomatoes from Spain, despite the transport costs involved – it cuts back on other causes of emissions, such as heated greenhouses.

Lamb from New Zealand has been similarly shown to have its transport emissions offset by other factors. Both are counter-intuitive but that doesn’t mean they aren’t true. We must aim for a lower environmental impact – but we should keep our approaches evidence-based. Trade can have other indirect, positive spill-overs on the environment too:

- encouraging innovation

- spurring investment in low-carbon production to meet standards in other countries

- lowering the costs of environmental goods and services

Indeed, a critical part of fighting climate change is improving local production processes. Trade and investment liberalisation can provide firms with incentives to adopt the high standards from elsewhere. Changes needed to meet these requirements, in turn, flow backwards along the supply chain. This stimulates the use of cleaner production processes and technologies throughout a country.

To encourage this, we have inserted environmental provisions into our agreements. Each of our comprehensive agreements has a chapter on Trade and Sustainable Development. Crucially, this helps us lock in commitments to implement international climate conventions, such as the Paris agreement. This is partly why our recent agreement with the four Mercosur states is so important.

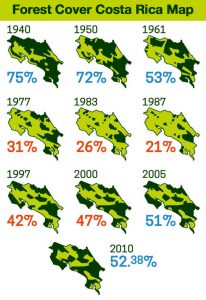

It binds these four countries together with the EU at a time when the US has left the Paris accord and is encouraging others to do so. Nevertheless, there are times when the evidence is there right before our eyes. We all saw the reports over the last couple of weeks of the fires raging in the Amazon rainforest.

This is deeply worrying – the Amazon provides much of the world’s oxygen and must be protected. I firmly believe that the EU-Mercosur agreement can be part of the solution. But I want to make it very clear that we expect Brazil to live up to its commitments on deforestation. These are not just empty words.

Unfortunately things currently seem to be going in the wrong direction – and if it continues this could complicate the ratification process in Europe.

Looking forward, the new Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen has said that she would like to look at border adjustment measures on carbon. This could encourage our trading partners to reduce their CO2 emissions. Instinctively, many have voiced doubts, referring to international trade rules. Any measures must be non-discriminatory and WTO compliant, of course, but that is not to say that it cannot be done. New challenges mean looking beyond what we think we know and breaking down our preconceptions. As ever with trade, the devil will be in the details.

FREE TRADE IS OUR ONLY GOAL

Upgrading and enforcing protections for the environment is just one area where trade can make a positive difference, but sustainable development is more than that. Our Generalised System of Preferences and Everything But Arms initiatives also play an important role. Both offer privileged access to EU markets to developing countries for meeting these environmental standards and more – in labour rights, human rights and social rights too. Because at the end of the day, trade is about much more than goods and services.

This is another presumption that we should tackle – that the endgame is pure free trade. Because trade is about economic prosperity, but it is also about:

It is about lifting people out of poverty, and it is a way to promote peace and trust between countries. Indeed, looking at our busy trade agenda, you see deals closed with many important partners. Mexico, Mercosur. Canada, Vietnam. South Korea, Singapore, Japan.

Each deal closed is the basis of a deeper relationship – many of which act as strategic alliances. This is important to our trade strategy at the moment. The EU needs friends – because we are trying to overcome one last misconception. Arguably the most dangerous one facing trade at the moment. The idea that the WTO is useless.

SLOWER MEANS WORSE

Not a lot of progress has been made at the WTO in recent years. This has led to some losing faith in it – whilst others take it for granted or disregard its rules But it is the system that has underpinned trade for decades. It is like oxygen – you would not notice it until it is gone, and then you are in serious trouble.

The end of the WTO would be the end of predictability in international trade. Businesses could no longer rely on exports as they once did – trade would become chaotic, unstable. Our trade policy, our economies and global value chains at large would reconfigure – and not always in the most efficient or desirable ways.

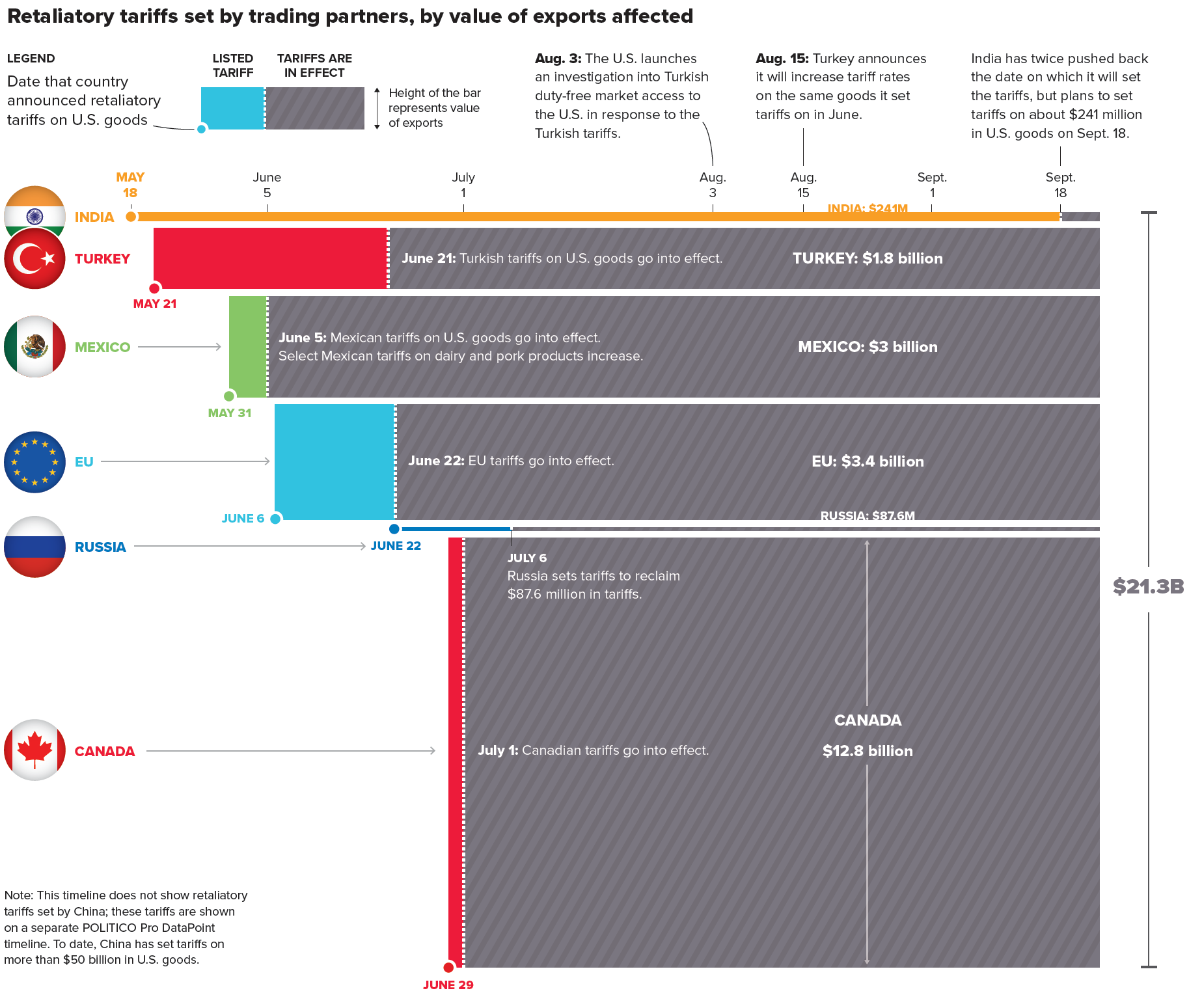

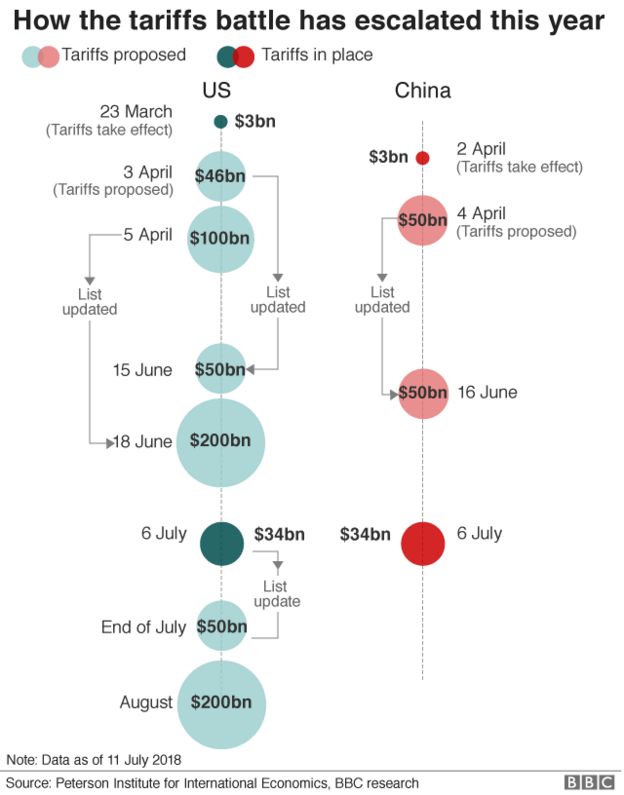

The WTO is critical to the functioning of global trade, but it is also out of date. We must update rules to tackle issues like illegal state subsidies. This would bring fairness back to the heart of global trade. We must also resolve the Appellate Body crisis. The Appellate Body brings discussion of the rules out of capitals to neutral ground – avoiding tit-for-tat tariffs and the escalation of trade tensions.

These are some of the immediate issues the WTO faces. In parallel, we need to work to show the organisation can still deliver. For example, in digital rulemaking. We are pleased that after years of attempts, we are finally seeing some progress. The WTO negotiations on e-commerce were launched in Davos with 80 countries in January this year. Proving the organisation can tackle 21st century issues helps demonstrate its value – but as important as the content is, the style of negotiation itself is crucial. We have gathered a smaller group of interested countries to move forward.

The EU has presented proposals on these issues and more. Other countries have too – this is good, it shows appetite for change. But we need broad buy in:

- from countries,

- from business,

- from all who have an interest in international trade.

Reforming and rebuilding faith in the WTO is a big task, and we will need all the allies we can get.

CONCLUSION

So now we have touched on a few of the broad misconceptions about trade: from tariffs to surpluses, benefits to environmental impacts. And we have seen that things are not as simple as they seem.

Life would be easier if we could simply follow our gut instincts. But society and policy are more complex than that. The best that we can do is hold on to our values – what we believe to be good and right – but always be ready to challenge received ideas through rigorous research and understanding. This is how truth will prevail in the end. This is how we move forward.

Thank you.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65359383/wwdc2019DSC_4114.0.jpg) Photo by Nilay Patel / The Verge

Photo by Nilay Patel / The Verge

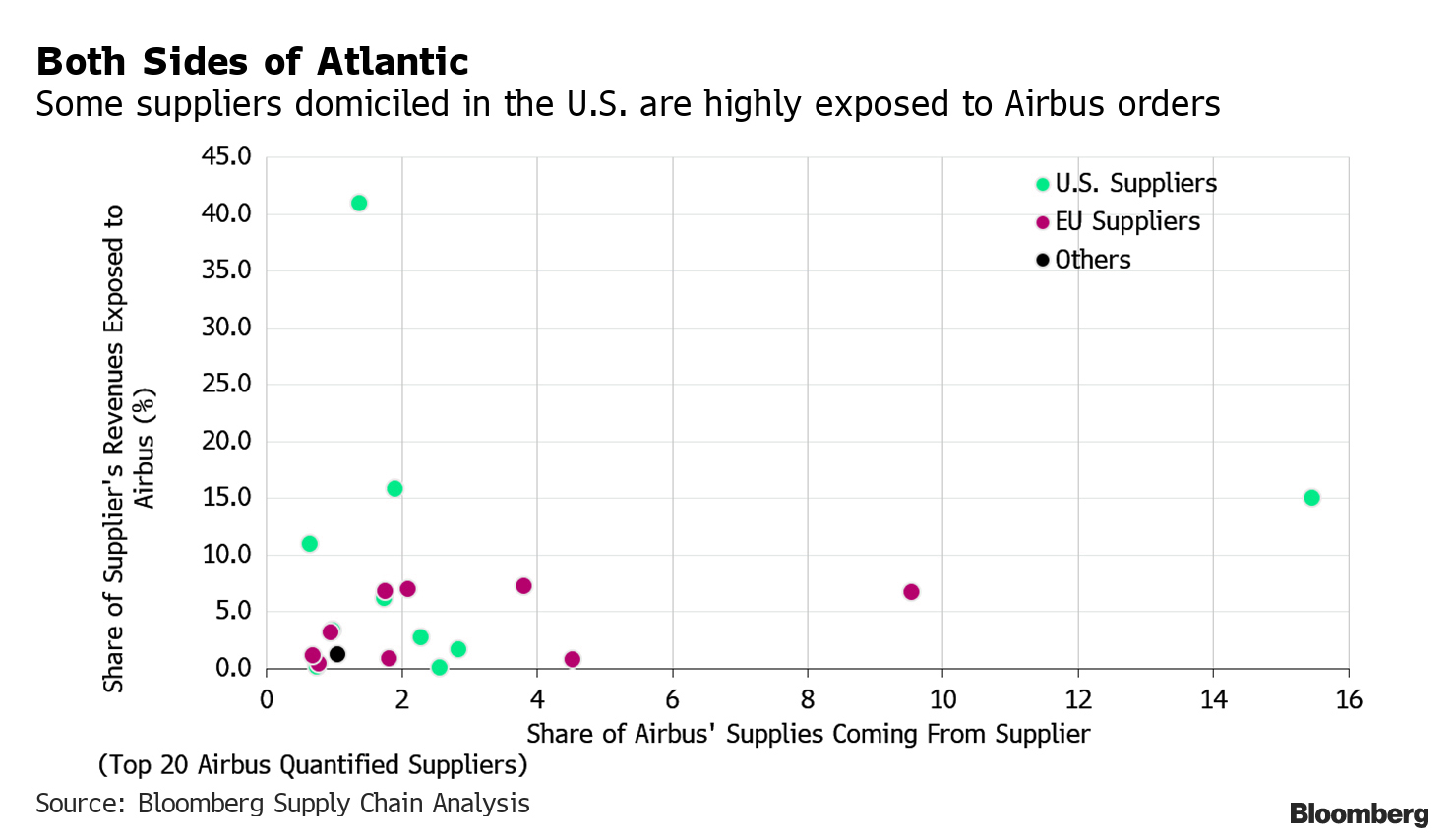

World Trade Organization authorized $7.5 billion in U.S. duties against the EU would hit export orders for U.S. manufacturers, according to Bloomberg Economics.

World Trade Organization authorized $7.5 billion in U.S. duties against the EU would hit export orders for U.S. manufacturers, according to Bloomberg Economics.

MIGRATION FALLS WHEN INCOMES RISE

MIGRATION FALLS WHEN INCOMES RISE According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF),

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF),

Source:

Source:

Sources:

Sources:

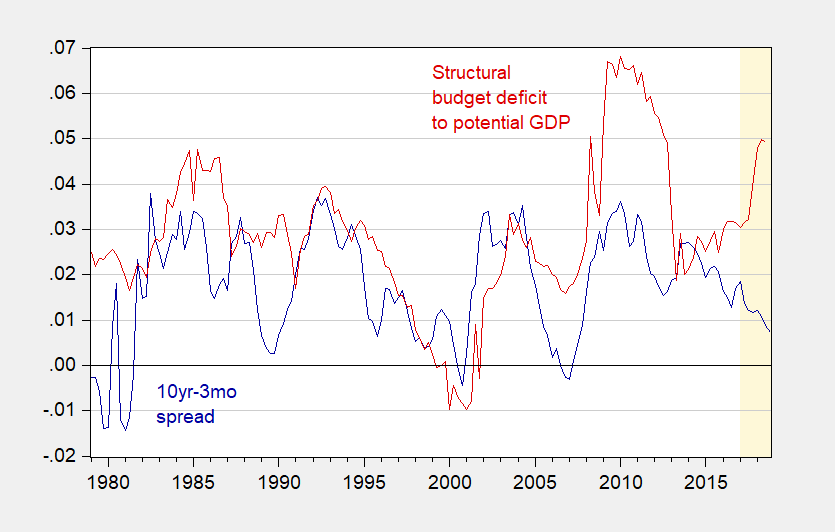

Figure 1: 10 year-3 month Treasury spread (blue), structural budget deficit as a share of potential GDP (red). Orange shading denotes Trump administration. Source: Federal Reserve, CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, and Chinn’s calculations.

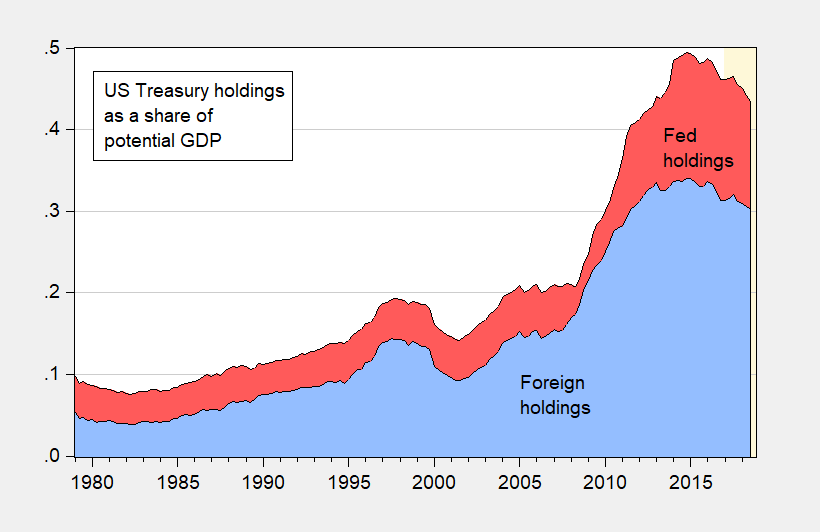

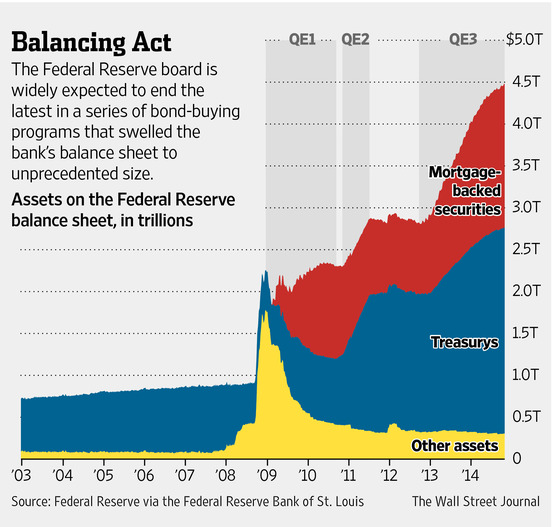

Figure 1: 10 year-3 month Treasury spread (blue), structural budget deficit as a share of potential GDP (red). Orange shading denotes Trump administration. Source: Federal Reserve, CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, and Chinn’s calculations. Figure 2: Foreign and international holdings of US Treasurys (blue) and Federal Reserve holdings (red), both as a share of potential GDP. Source: BEA, CBO, and Chinn’s calculations.

Figure 2: Foreign and international holdings of US Treasurys (blue) and Federal Reserve holdings (red), both as a share of potential GDP. Source: BEA, CBO, and Chinn’s calculations.

![Toxic Pearl: Pacific Northwest Shellfish Companies' Addiction to Pesticides? by [Perle, M.]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/41yrgTY7ohL.jpg)

(source)

(source) (

(

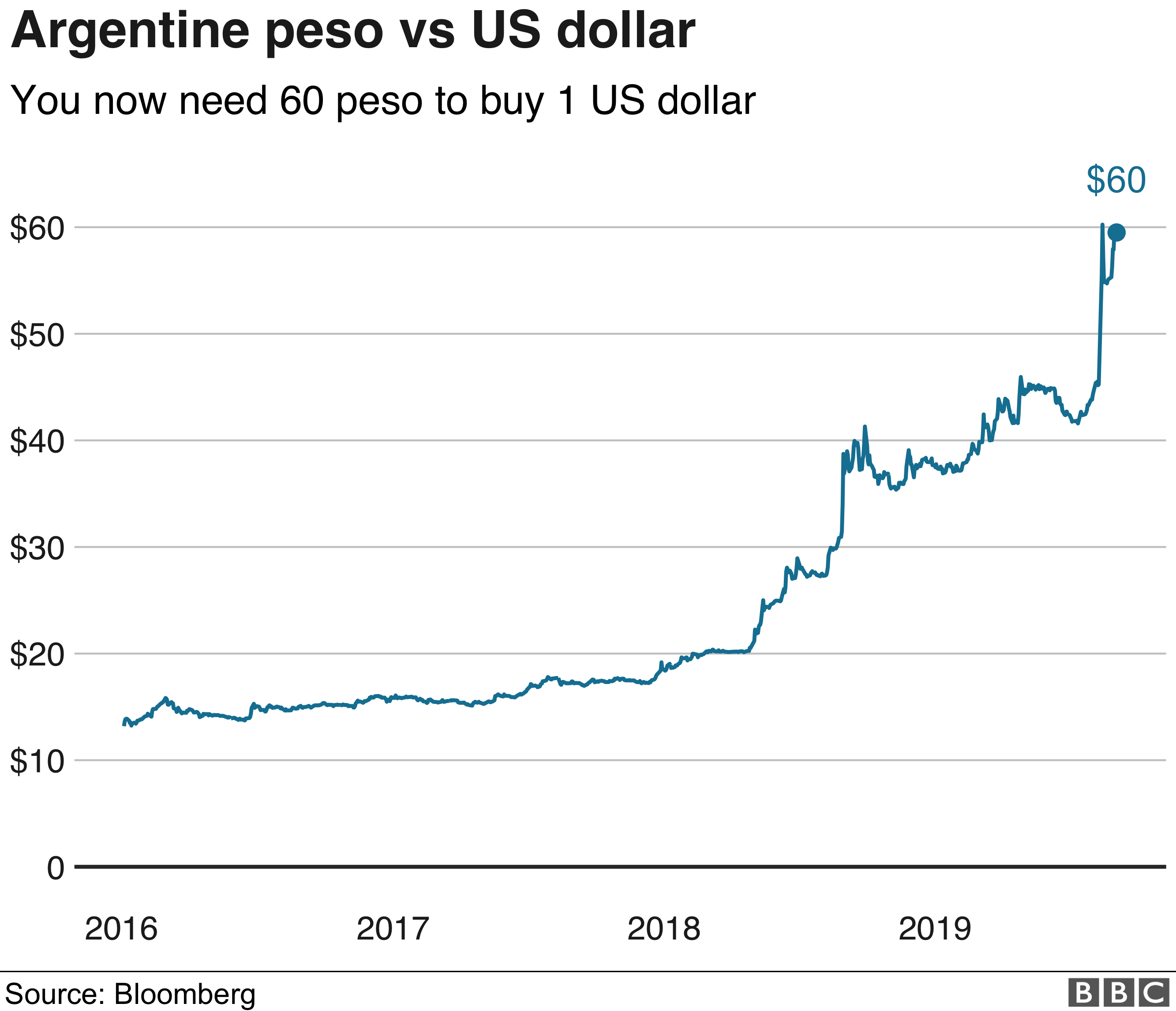

This explains pictures circulating on the web asking people NOT to use banknotes as toilet paper… Also, imagine the volume of money needed to buy a car!

This explains pictures circulating on the web asking people NOT to use banknotes as toilet paper… Also, imagine the volume of money needed to buy a car!

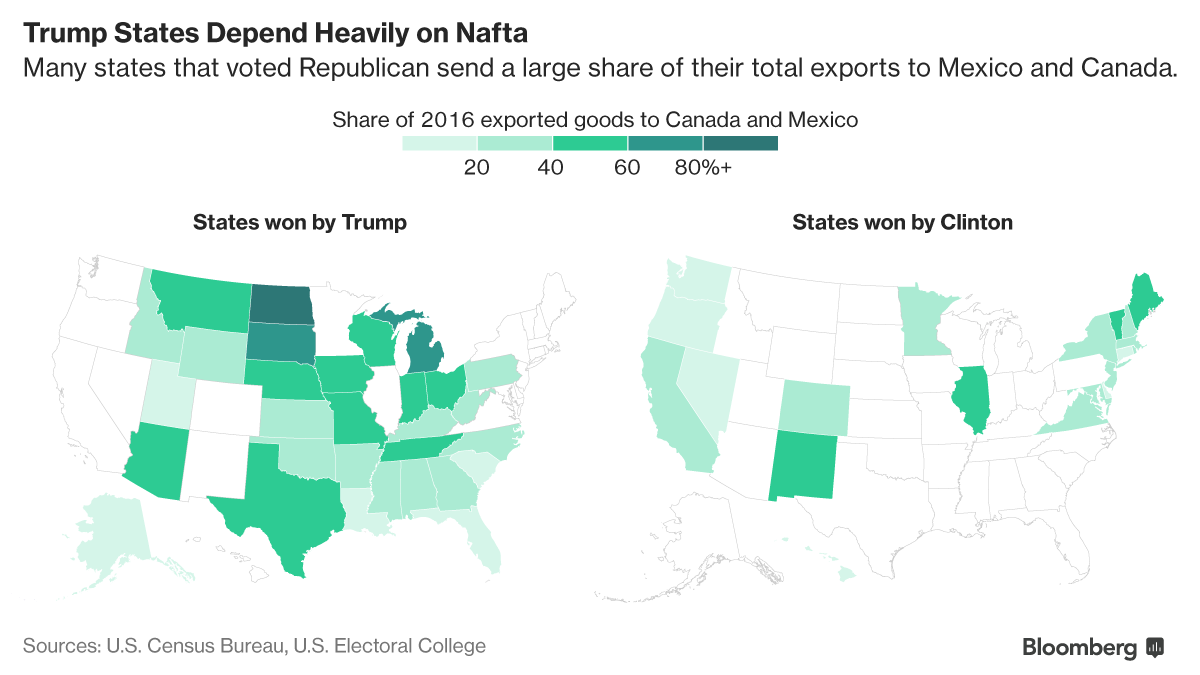

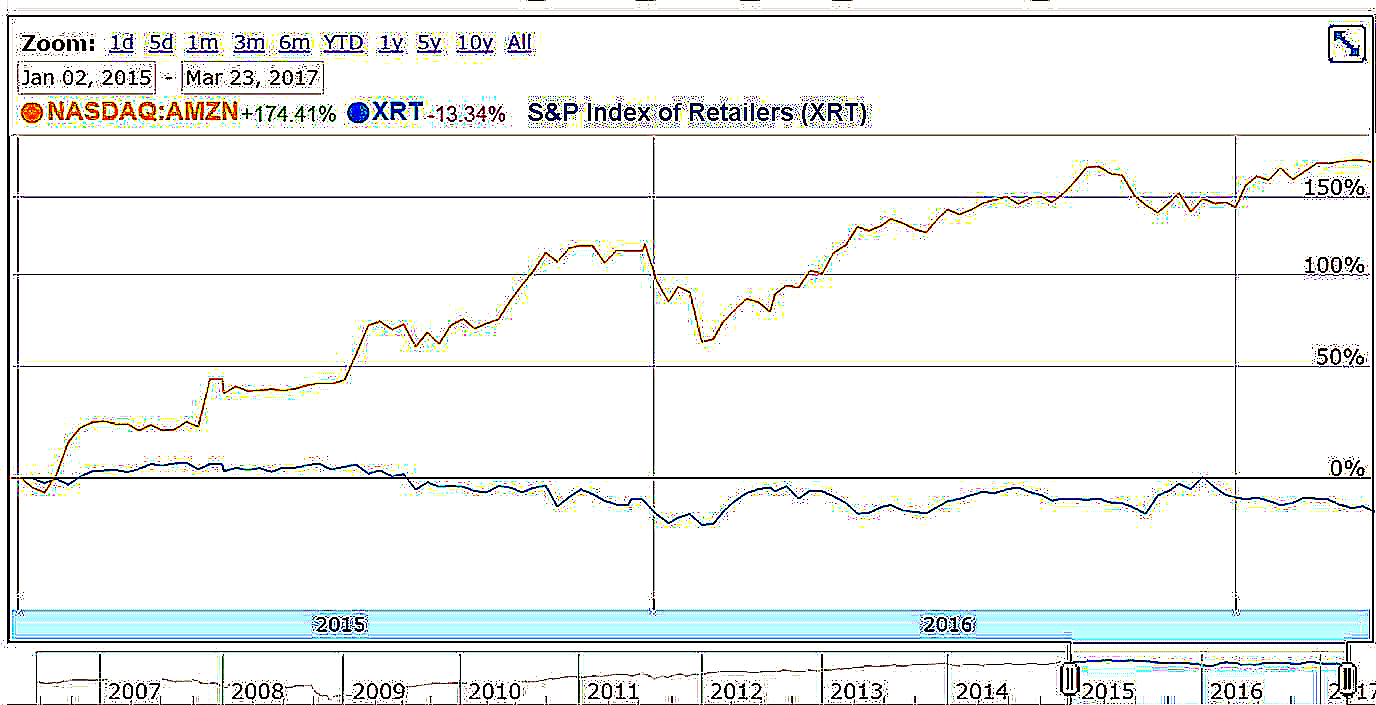

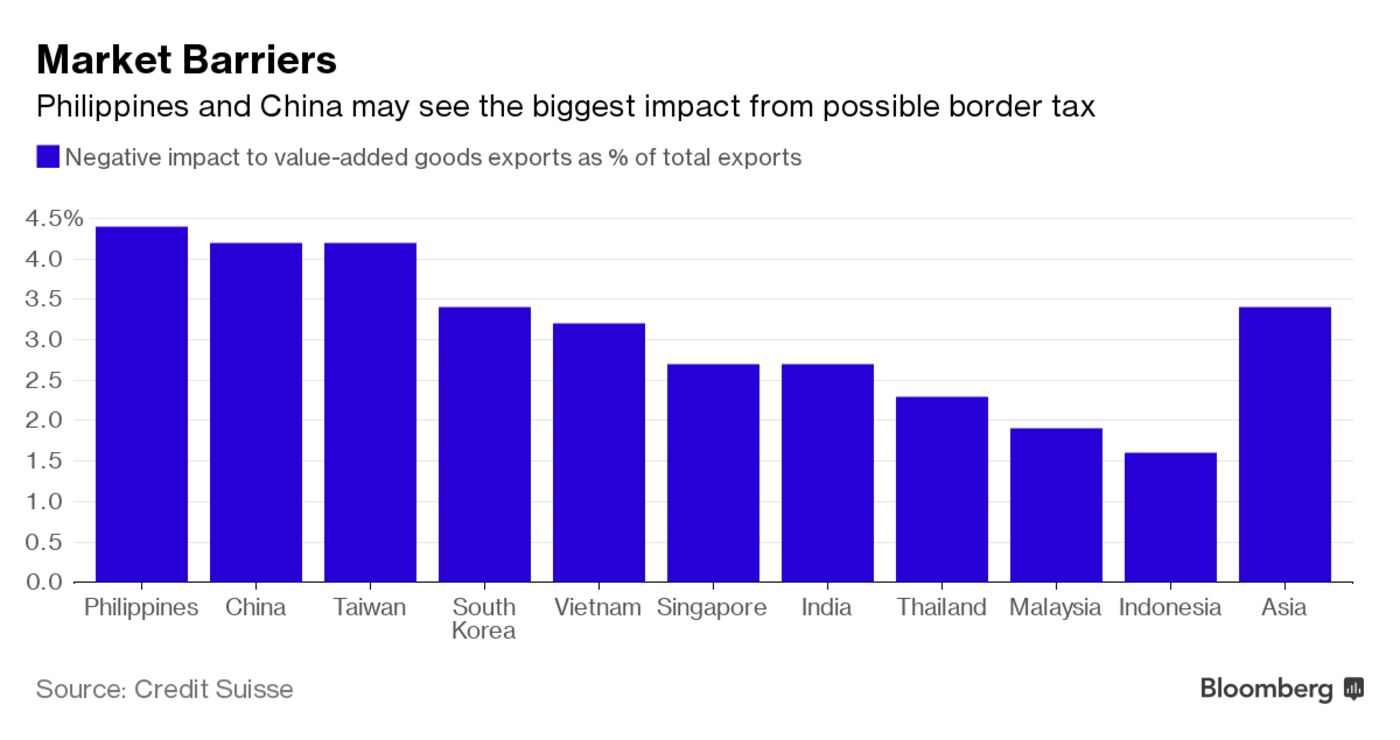

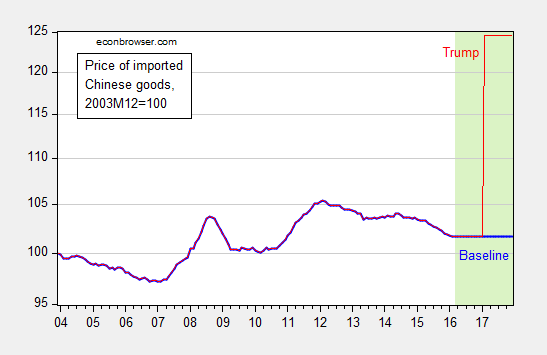

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

–

–

[2]___Super_Portrait.jpg)

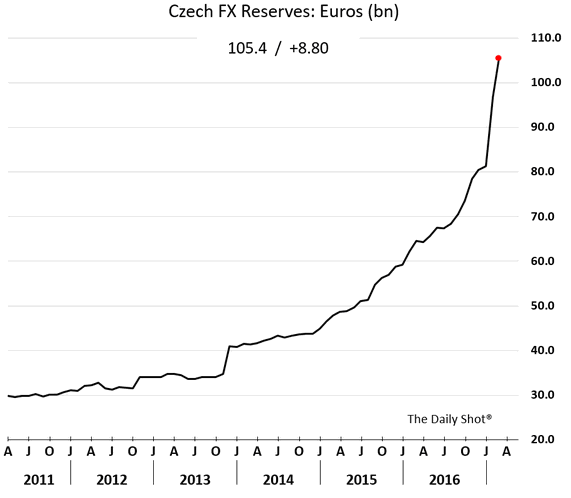

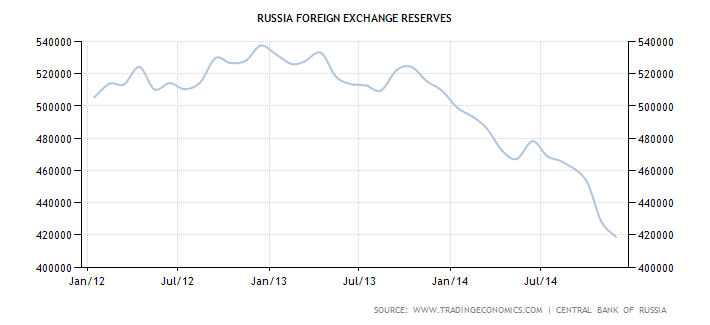

Maintaining a fixed exchange rates implies a cap on the price of foreign currency which has forced the central bank to keep buying euros (and selling koruna) to make sure the koruna doesn’t appreciate above the target level. This policy has resulted in the CNB holding huge amounts of euros.

Maintaining a fixed exchange rates implies a cap on the price of foreign currency which has forced the central bank to keep buying euros (and selling koruna) to make sure the koruna doesn’t appreciate above the target level. This policy has resulted in the CNB holding huge amounts of euros.

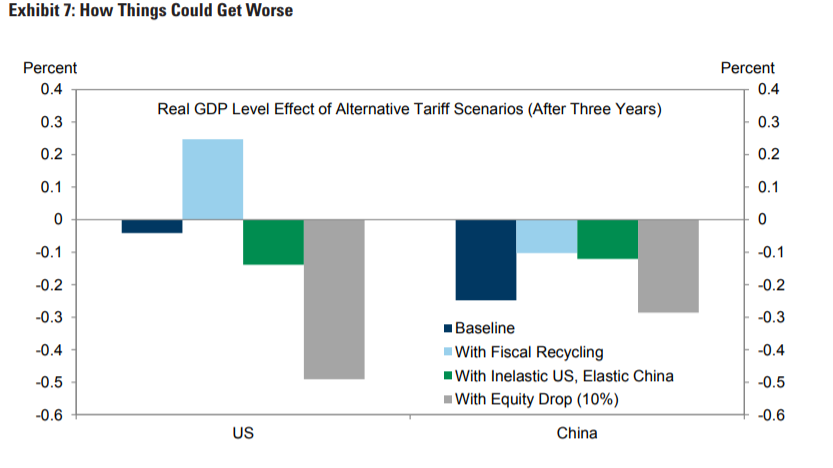

Source: Goldman Sachs, @joshdigga

Source: Goldman Sachs, @joshdigga Source: @fastFT

Source: @fastFT

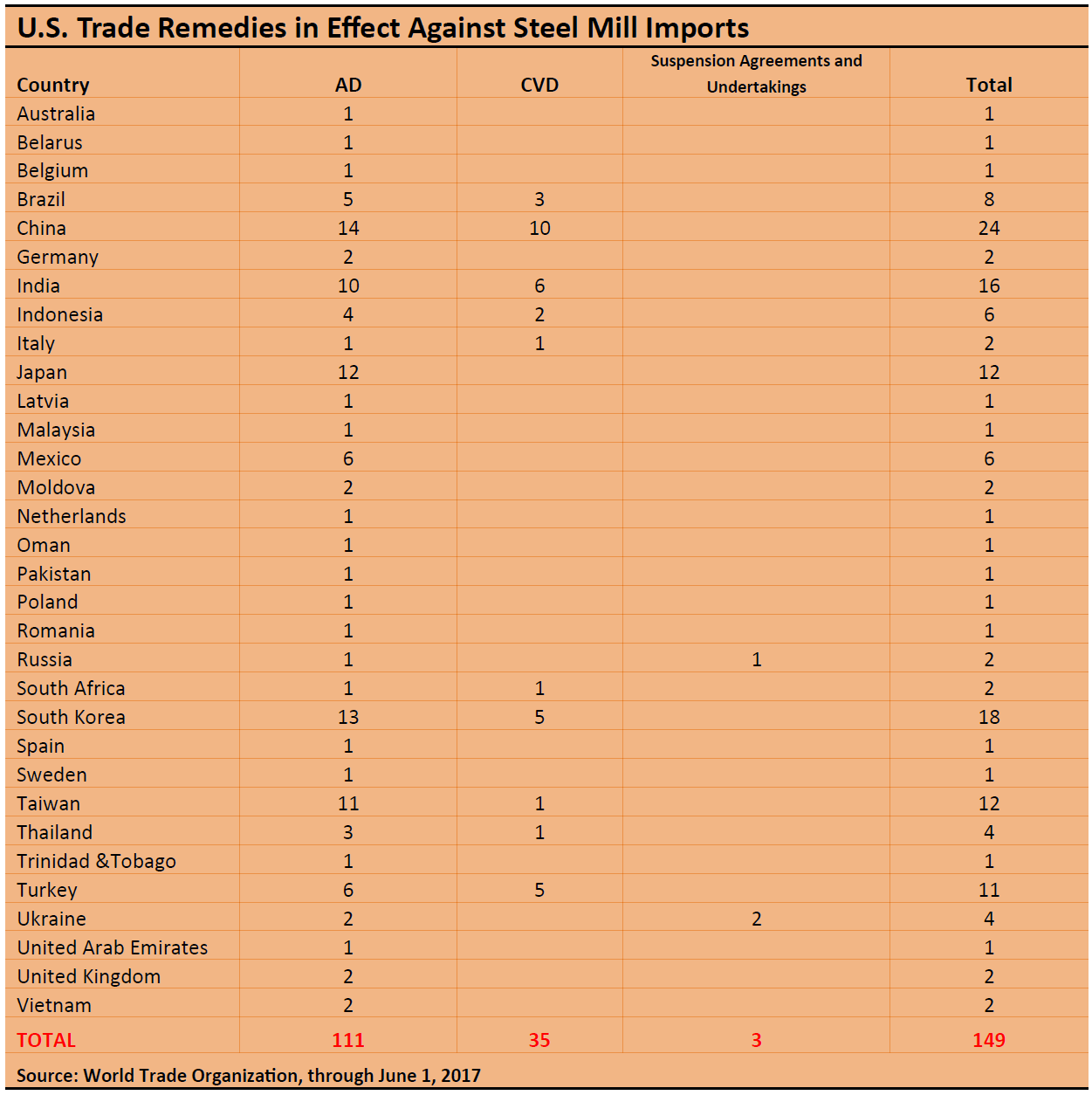

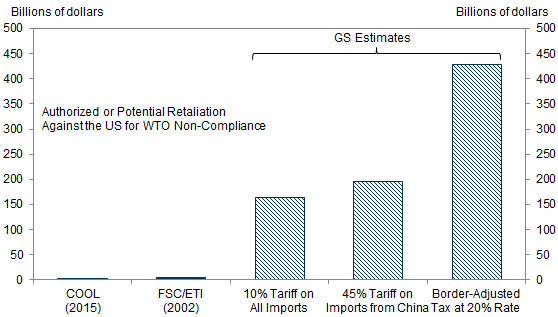

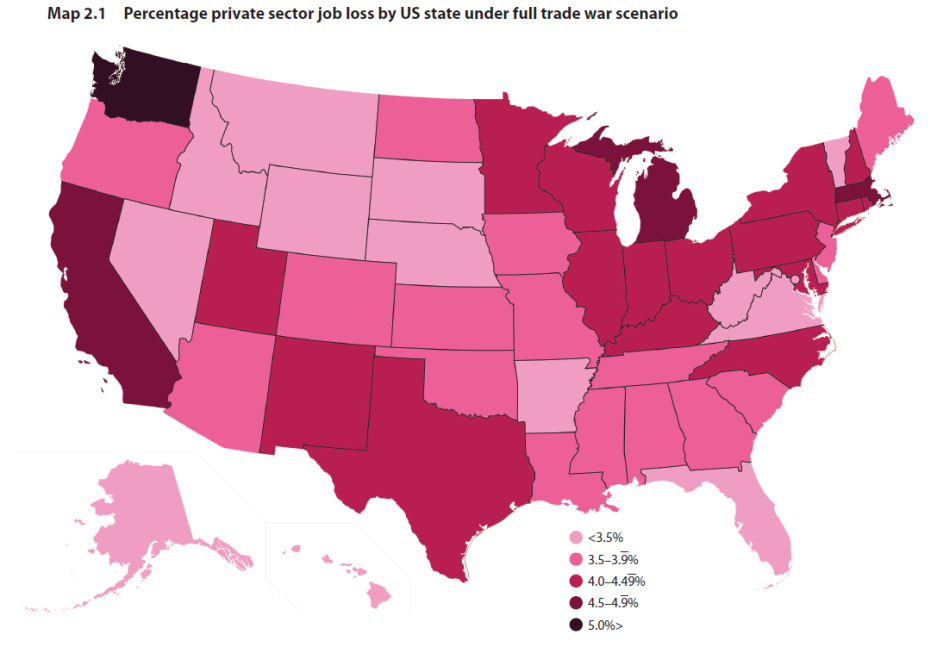

Source:Mericle and Phillips, “US Daily: Trade Disputes: What Happens When You Break the Rules?” Goldman Sachs, February 17, 2017 (not online), based on data from World Trade Organization, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

Source:Mericle and Phillips, “US Daily: Trade Disputes: What Happens When You Break the Rules?” Goldman Sachs, February 17, 2017 (not online), based on data from World Trade Organization, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

It is pretty hard to square those two data points. UK data is from the Office of National Statistics’

It is pretty hard to square those two data points. UK data is from the Office of National Statistics’  And the UK thinks it sells more services to the U.S. than the U.S. thinks it buys.

And the UK thinks it sells more services to the U.S. than the U.S. thinks it buys. My guess is that such discrepancies are actually common in the services trade numbers. Goods trade is calculated by customs bureaus. Lots of the numbers on services trade come from surveys, estimates, and the like.

My guess is that such discrepancies are actually common in the services trade numbers. Goods trade is calculated by customs bureaus. Lots of the numbers on services trade come from surveys, estimates, and the like.

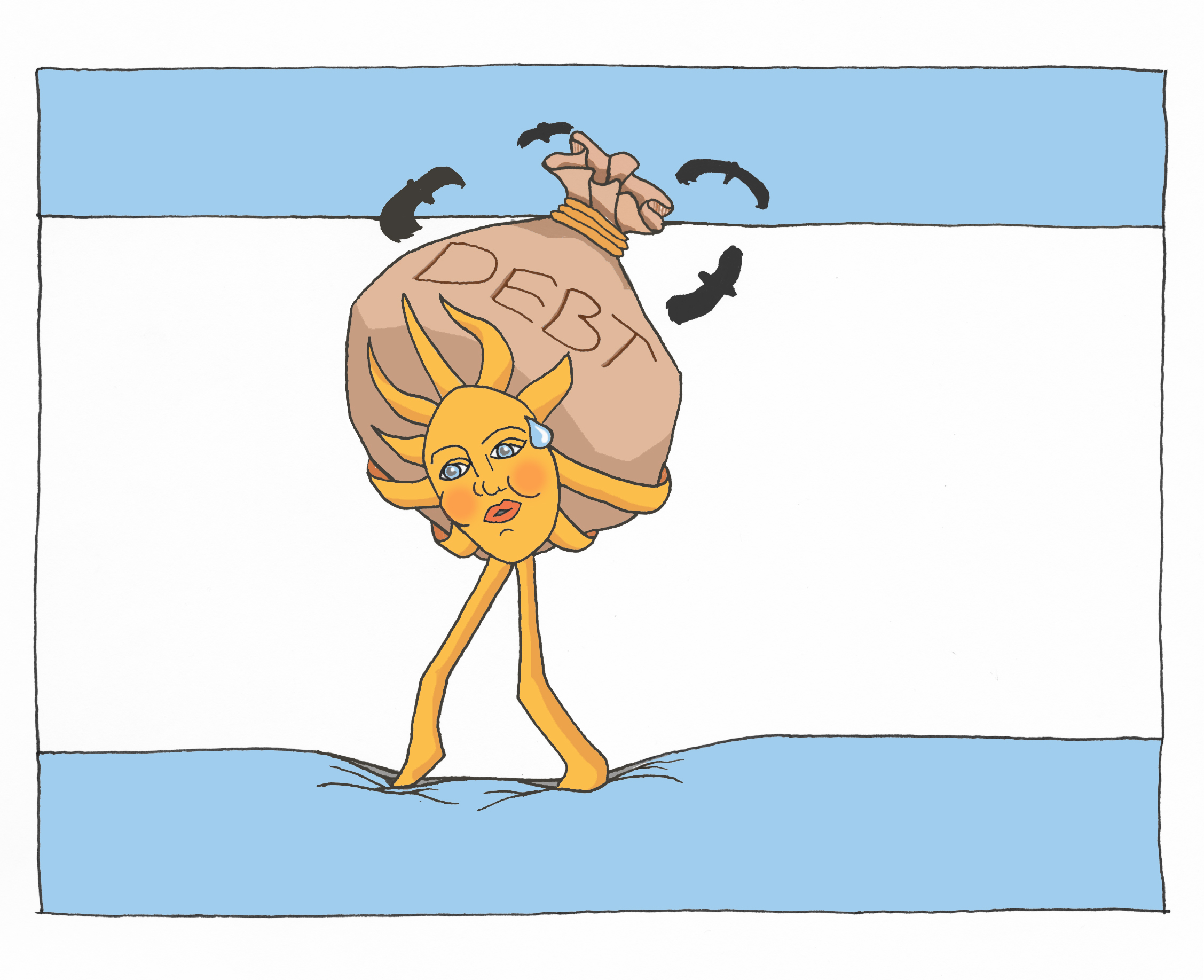

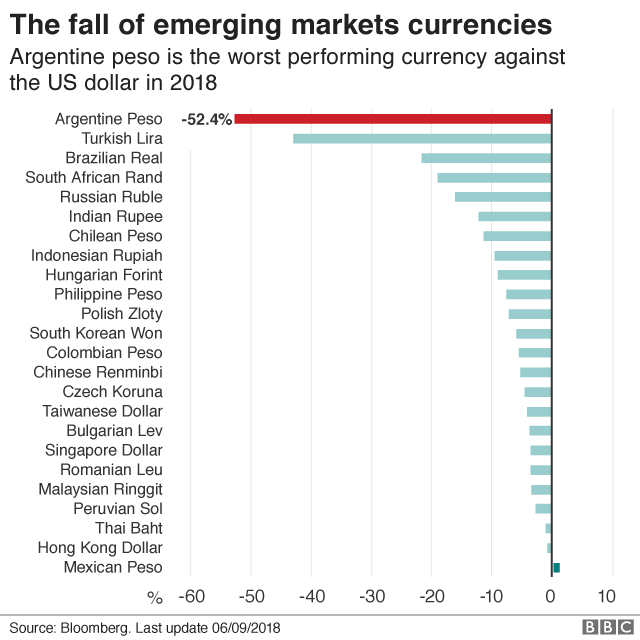

CERNOBBIO – Investors and economic observers have begun to ask the same question that I posed in an article published 18 years ago: “Who lost Argentina?” In late 2001, the country was in the grips of an intensifying blame game, and would soon default on its debt obligations, fall into a deep recession, and suffer a lasting blow to its international credibility. This time around, many of the same contenders for the roles of victim and accuser are back, but others have joined them. Intentionally or not, all are reprising an avoidable tragedy.

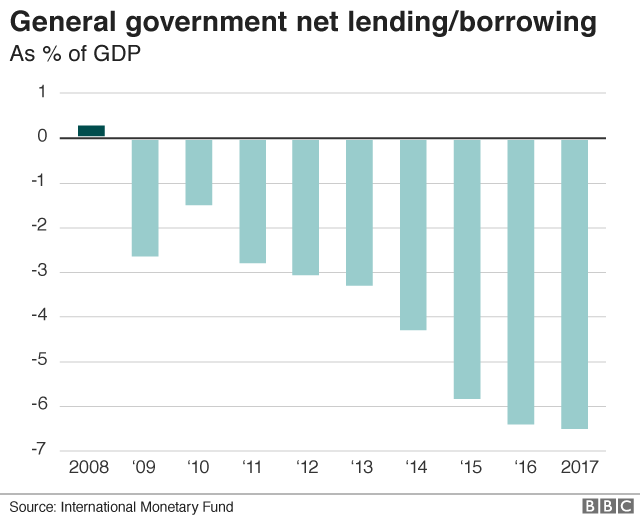

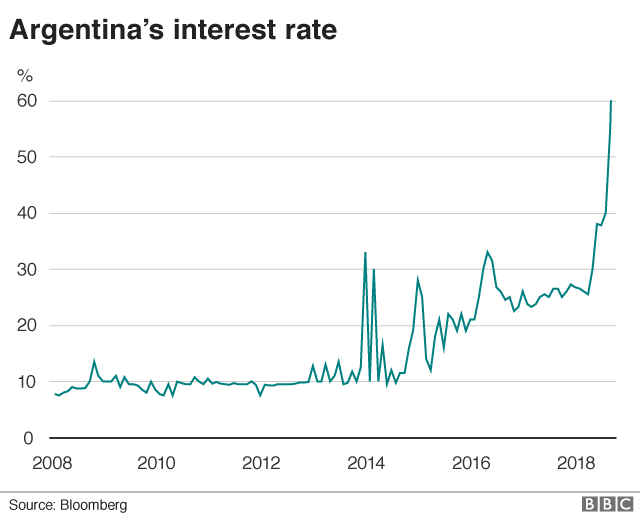

After a poor primary-election outcome, Argentinian President Mauricio Macri finds himself running for another term under economic and financial conditions that he promised would never return. The country has imposed capital controls and announced a reprofiling of its debt payments. Its sovereign debt has been downgraded deeper into junk territory by Moody’s, and to selective default by Standard & Poor’s. A deep recession is underway, inflation is very high, and an increase in poverty is sure to follow.

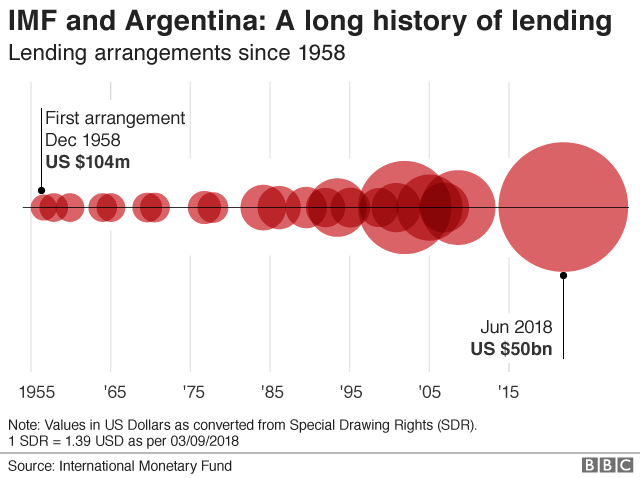

It has not even been four years since Macri took office and began pursuing a reform agenda that was widely praised by the international community. But since then, the country has run into trouble and become the recipient of record-breaking support from the International Monetary Fund.

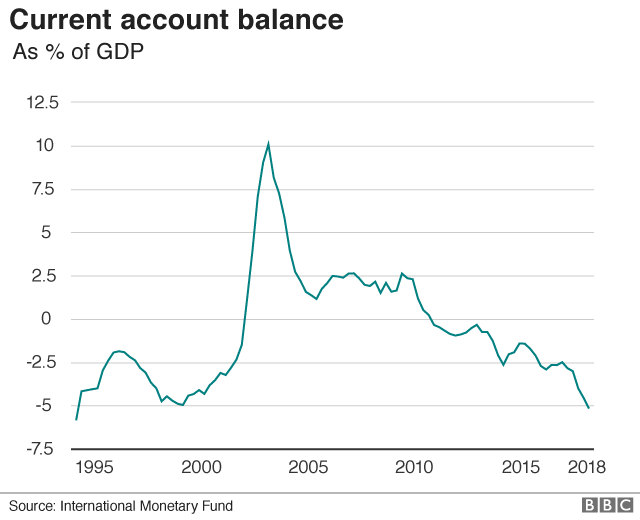

Argentina has fallen back into crisis for the simple reason that not enough has changed since the last debacle. As such, the country’s economic and financial foundations have remained vulnerable to both internal and external shocks.

Although they have been committed to an ambitious reform program, Argentina’s economic and financial authorities have also made several avoidable mistakes. Fiscal discipline and structural reforms have been unevenly applied, and the central bank has squandered its credibility at key moments.

More to the point, Argentinian authorities succumbed to the same temptation that tripped up their predecessors. In an effort to compensate for slower-than-expected improvements in domestic capacity, they permitted excessive foreign-currency debt, aggravating what economists call the “original sin”: a significant currency mismatch between assets and liabilities, as well as between revenues and debt servicing.

Worse, this debt was underwritten not just by experienced emerging-market investors, but also by “tourist investors” seeking returns above what was available in their home markets. The latter tend to lack sufficient knowledge of the asset class into which they are venturing, and thus are notorious for contributing to price overshoots – both on the way up and the way down.

Undeterred by Argentina’s history of chronic volatility and episodic illiquidity – including eight prior defaults – creditors gobbled up as much debt as the country and its companies would issue, including an oversubscribed 100-year bond that raised $2.75 billion at an interest rate of just 7.9%. In doing so, they drove the yields of Argentine debt well below what economic, financial, and liquidity conditions warranted, which encouraged Argentine entities to issue even more bonds despite the weakening fundamentals.

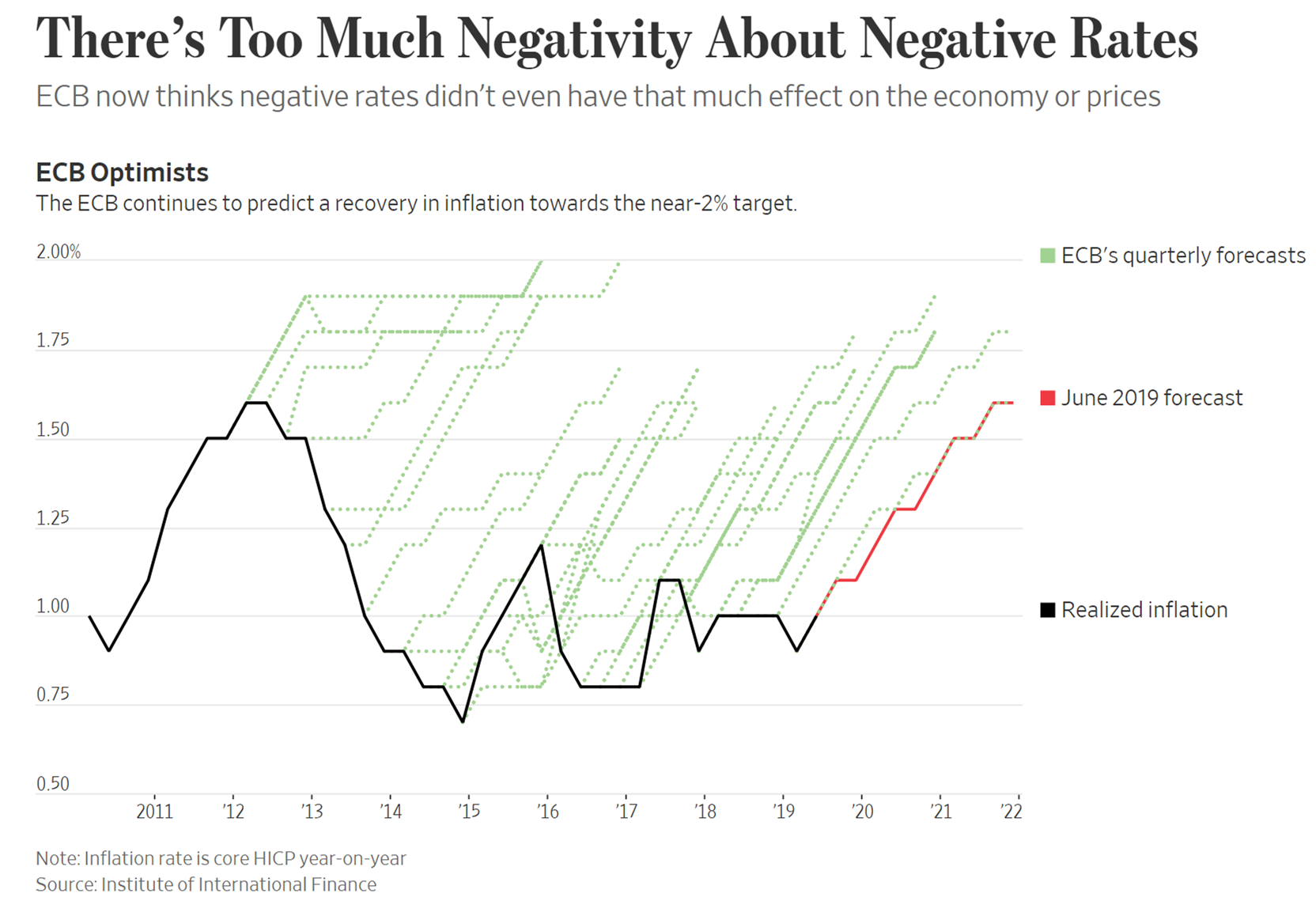

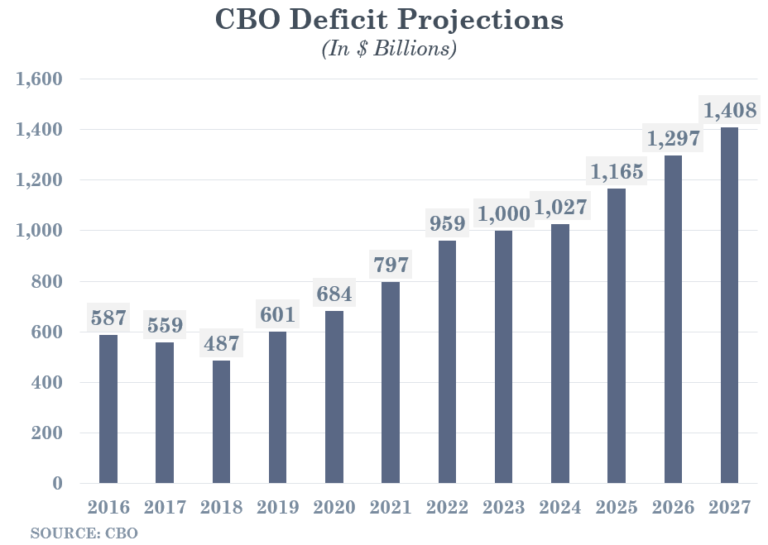

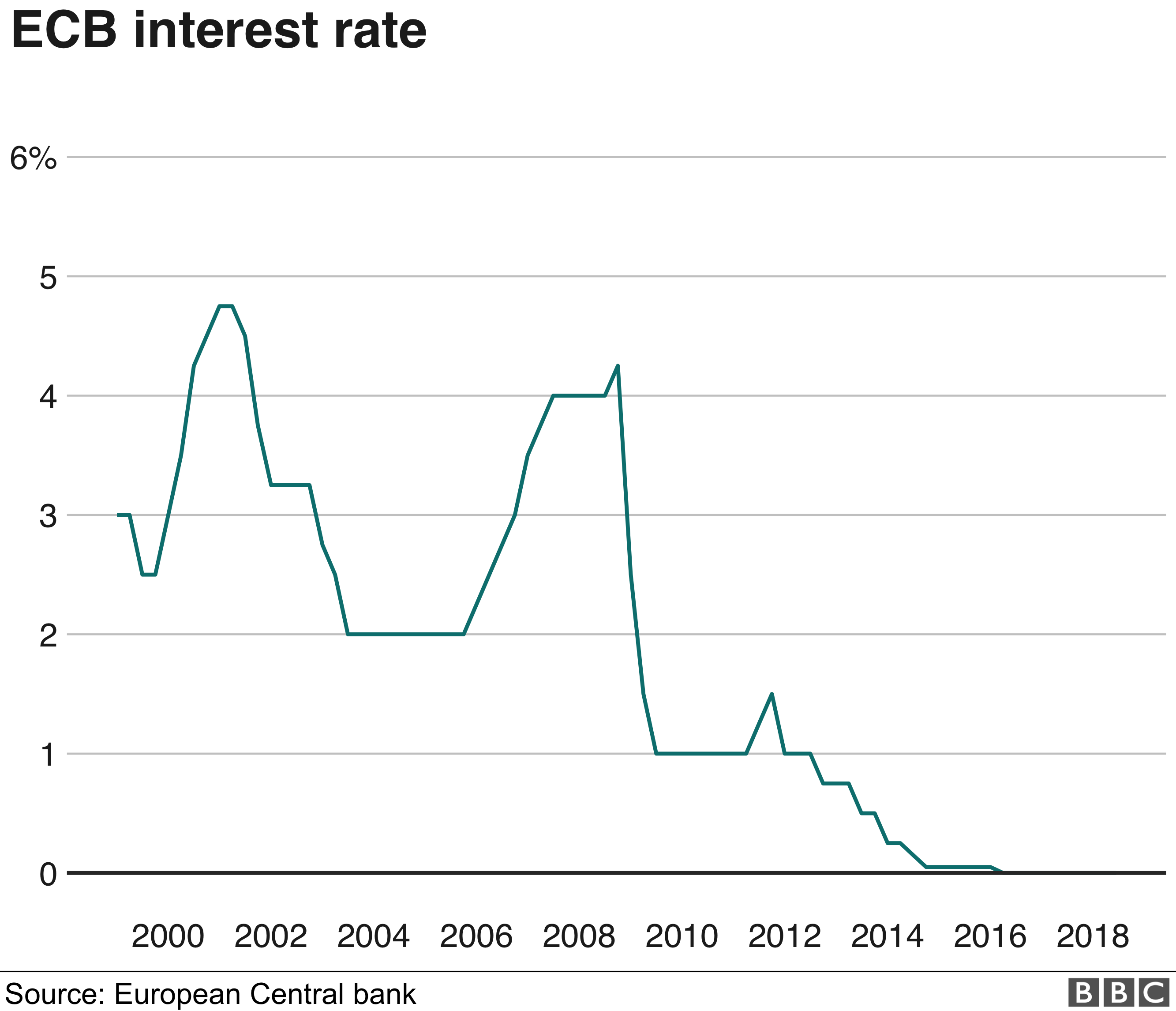

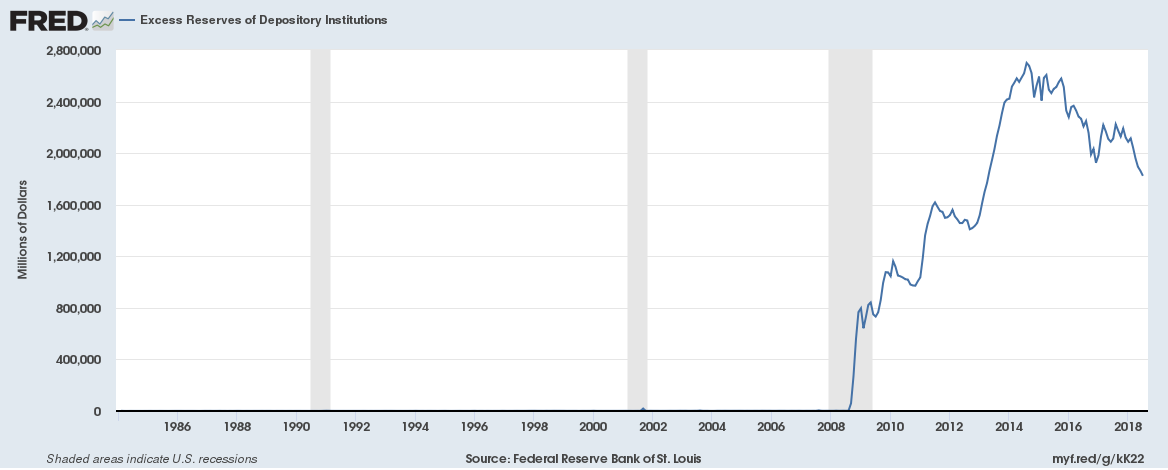

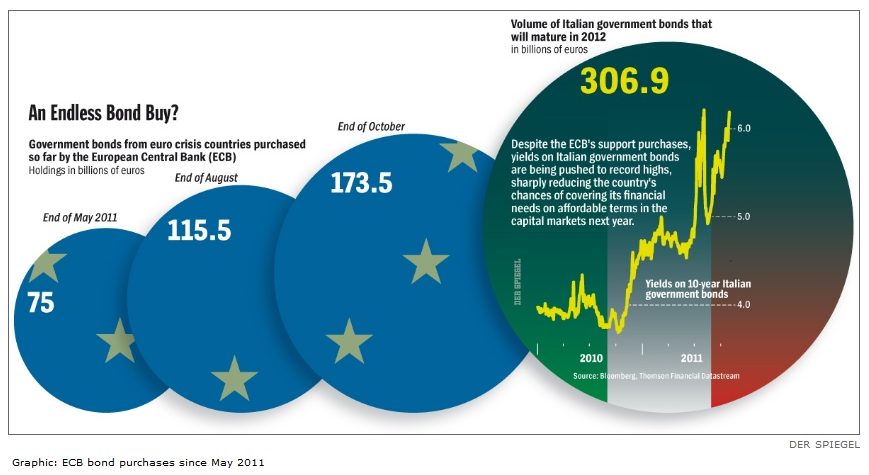

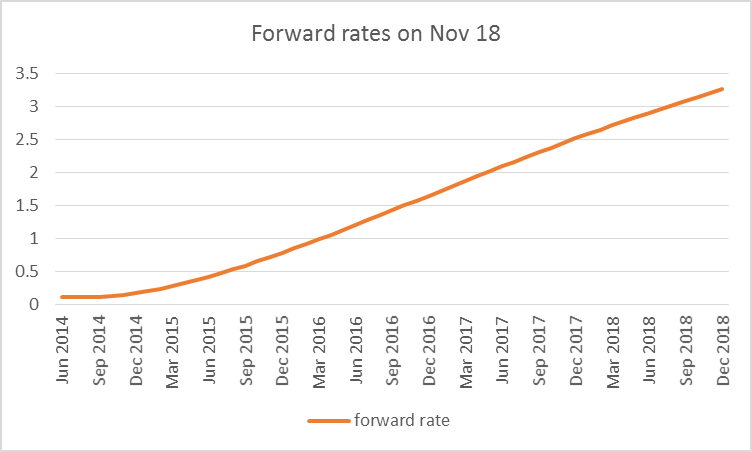

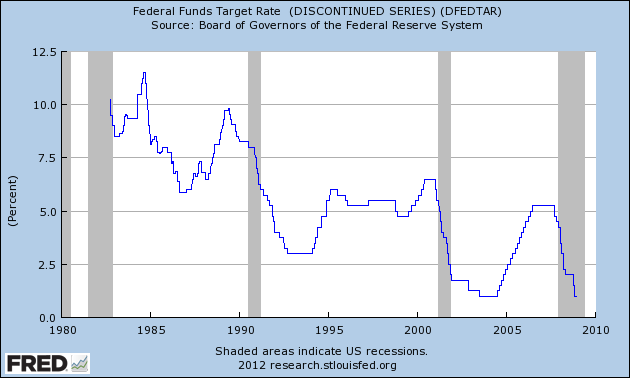

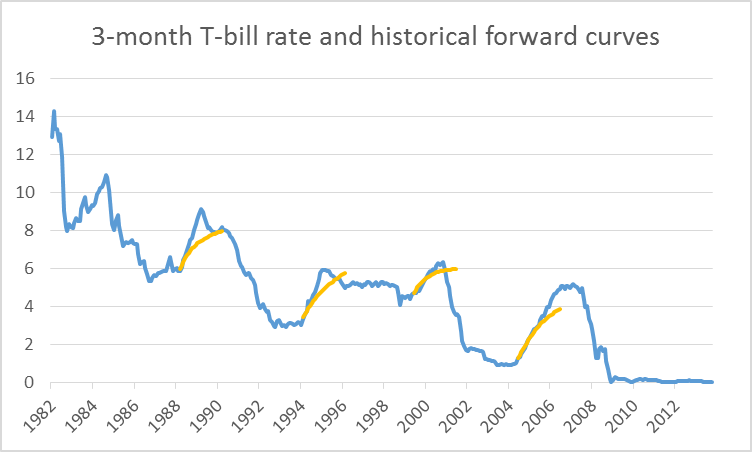

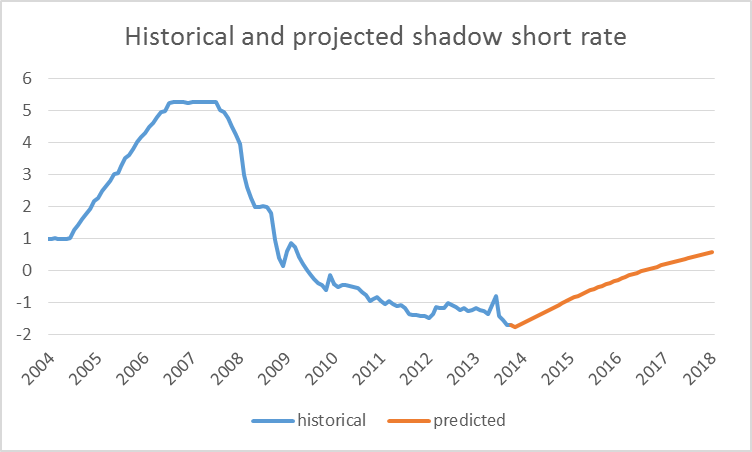

The search for higher yields has been encouraged by unusually loose monetary policies – ultra-low (and, in the case of the European Central Bank, negative) policy rates and quantitative easing – in advanced economies. Systemically important central banks (the Bank of Japan, the US Federal Reserve, and the ECB) thus have become the latest players in the old Argentine blame game.

Moreover, influenced by years of strong central-bank support for asset markets, investors have been conditioned to expect ample and predictable liquidity – a consistent “common global factor” – to compensate for all sorts of individual credit weaknesses. And this phenomenon has been accentuated by the proliferation of passive investing, with the majority of indices heavily favoring outstanding market values (hence, the more debt an emerging market issues, like Argentina, the higher its weight in many indices becomes).

Then there is the IMF, which readily stepped in once again to assist Argentina when domestic-policy slippages made investors nervous in 2018. So far, Argentina has received $44 billion under the IMF’s largest-ever funding arrangement. Yet, since day one, the IMF’s program has been criticized for its assumptions about Argentina’s growth prospects and its path to longer-term financial viability. As it happens, the same issues plagued the IMF’s previous efforts to Argentina, including in the particularly messy lead-up to the 2001 default.

As in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, almost everyone involved has had a hand in Argentina’s ongoing economic and financial debacle, and all are victims themselves, having suffered reputational harm and, in some cases, financial losses. Yet those costs pale in comparison to what the Argentine people will face if their government does not move quickly – in cooperation with private creditors and the IMF – to reverse the economic and financial deterioration.

Whoever prevails at next month’s presidential election, Argentina’s government must reject the notion that its only choice is between accepting and refusing all demands from the IMF and external creditors. Like Brazil under then-President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva in 2002, Argentina needs to embark on a third path, by developing a homegrown adjustment and reform program that places greater emphasis on protecting the most vulnerable segments of society. With sufficient buy-in from domestic constituencies, such a program would provide an incentive-aligned path for Argentina to pursue its recovery in cooperation with creditors and the IMF.

Given the downturn in the global economy and the rising risk of global financial volatility, there is no time to waste. Everyone with a stake in Argentina has a role to play in preventing a repeat of the depression and disorderly default of the early 2000s. Managing a domestic-led recovery will not be easy, but it is achievable – and far better than the alternatives.”