| Clinical Leadership | |||||||||||

|

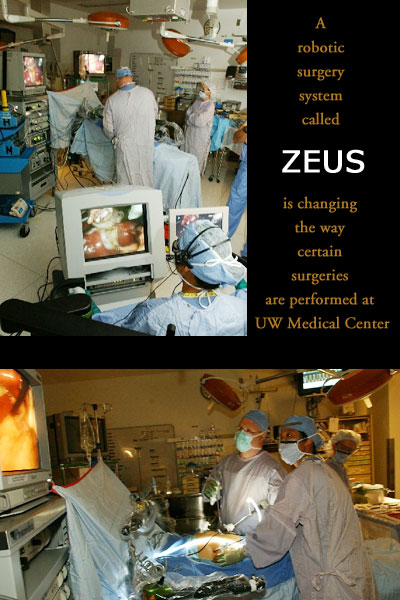

Robitic Surgery a Reality at UW Medical Center |

|||||||||||

The system, which has received FDA approval, was tested at UW Medical Center in late 2002. Surgeons from many disciplines received two months of training on the equipment before performing procedures on patients who had volunteered to have their surgeries through part laproscopic and part robotic techniques. The results were so promising that a Zeus system was purchased, and full-scale training for surgical teams began in April 2003. In spite of its futuristic name, robotic surgery is not performed by a humanoid automaton. Rather, robotic surgery interposes a computer between the surgeon and the surgical tools operating on the patient's tissue. This enhances the surgeon's ability to precisely control the procedure. Dr. Lily Chang, assistant professor in the Division of General Surgery, has worked closely on the robotic surgery program under the direction of Dr. Mika Sinanan. As an associate professor of surgery and an adjunct associate professor of electrical engineering, Sinanan is well-suited to lead the effort. "Robotic surgery is not experimental technology,” Chang said. “It has been proven to be safe, efficacious, and as good as traditional operations. The question is, 'Can we make this system better than traditional surgery for a full range of procedures?' " Expanding the potential of robotic surgery will require looking at robotic techniques for their clinical potential, coming up with new applications, and applying innovative thinking. Just as laproscopic surgery offers advantages over traditional open surgery for certain procedures, robotic surgery can improve laproscopic techniques. In laproscopic surgery, the surgeon employs a tiny camera and long instruments that allow for a smaller incision. Depending on the procedure, minimally invasive surgery usually reduces pain, infections and post-operative complications, and speeds recovery. However, the long instruments required for laproscopic surgery produce a fulcrum effect in which the working end of the instrument goes in the opposite direction from that of shorter instruments used in open surgery. This can be uncomfortable and tiring for the surgeon who must hold and manipulate the instruments at strange angles, sometimes over long periods of time. The assistance of the computer in robotic surgery reduces fatigue and hand tremors as it enhances speed and accuracy. This kind of assistance is especially important for surgeries performed in small, tight spaces such as the pelvis. Robotic surgery restores the range of motion and freedom of movement of the hand and wrist that are lost in laproscopic surgery. In addition, it provides motion scaling, the ability to translate the motion of the surgeon's hand into precisely increased or decreased movements. Motion scaling promises to be helpful in cardiac surgery and neurosurgery where fine, exact movements are necessary. While laproscopic surgery relies on a two-dimensional camera, robotic surgery uses a three-dimensional scope that aids in depth perception. Voice controlled responders help the surgeons manage and position the camera by reacting to spoken commands such as in or out, left or right. The computers in robotic surgery provide data for surgeons to integrate with other information, such as X-rays. Future advances are expected to make it possible for surgeons to rehearse and simulate a specific operation in a virtual reality setting. As Chang points out, "Almost every other activity that requires expertise, from sports to music to theater, depends on rehearsing to perfect techniques. Computers and robotics can give surgeons a way to rehearse by simulating surgical procedures. Such practice will improve outcomes and safety." The Department of Surgery has joined with the Department of Engineering for the past decade to design laproscopic procedures. A collaboration with the Human Interface Technology Lab will explore virtual reality capabilities. Chang noted that robotics and computers are not new in medicine. They have been used for stereotactic biopsies of the brain and breast for years. "You can imagine the advantage of giving a computer the x, y and z coordinates for a biopsy,” she said,” and then telling it to get there with no hand tremors or inaccuracies." Like the first computers, this first generation of surgical robotic systems is large and somewhat cumbersome. "There is no doubt that current robotic systems are safe and efficient for specific parts of an operation. To become efficient for all parts of the operation, they must be made smaller and more modular," said Chang. In these early stages of robotic surgery, patients' responses to the possibility of having their surgeries performed using robotic techniques range from enthusiasm to "no way." Chang believes fears about robotic surgery are unfounded. "Computers are not about to replace surgeons. A surgeon must provide the knowledge to do the right surgery, and the ability to interact with and reassure patients. Patients want their doctors, but so much of medicine can be improved with computers." |

|||||||||||

|

© 2003 - 2004 UW Medicine

Maintained by UW Health Sciences and Medical Affairs News and Community Relations Send questions and comments to drrpt@u.washington.edu |

|||||||||||