| Research | ||||||||||||||||

|

Gastroenterologist Witnesses a Half-century of Changes in His Field |

||||||||||||||||

|

He may be 82 years old, but Dr. Cyrus Rubin is showing no signs of slowing down his academic career. Rubin, professor emeritus of medicine, is still doing science and gastroenterology research in the RR-wing of University of Washington Medical Center. Since joining the UW faculty in 1953, Rubin has trained over 40 gastroenterologists, more than half of whom became academic physicians.

"It's been a good life for me here," said Rubin. "The combination of being able to diagnose cancer and other diseases in endoscopic biopsies every day, as well as teaching these incredibly bright, young specialists in GI pathology gives me great joy." According to Rubin, the late Dr. Wade Volwiler, who founded the UW Division of Gastroenterology, together with a handful of other gastroenterologists, changed the field to a more research-based specialty. "When I came to the UW more than 50 years ago there was only one other person in the whole Division, Dr. Wade Volwiler," said Rubin. "We had no university hospital. All our teaching was done at the Veterans Administration Hospital and Harborview Medical Center. Gastroenterology, in general, was an empiric, anecdotal specialty. Physiologists were always doing good work in the area, but they were rarely practicing gastroenterologists." Rubin established himself as a leading authority on the microscopic structure of the gastrointestinal lining or mucosa. He has received international recognition for his many accomplishments, including the major awards of all three American gastroenterological organizations: the Distinguished Achievement Award and the Friedenwald Medal from the American Gastroenterology Association; the Rudolph Schindler Award from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; and the Clinical Research Award from the American College of Gastroenterology. Rubin earned an M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1945 and served as an officer in the U. S. Army Medical Corps. He rose to the rank of captain. Rubin completed a residency in internal medicine at Cushing Veterans Administration Hospital in Framingham, Mass., and a medical internship and one-year residency in radiology at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston. At that time, radiology was the main diagnostic tool used in gastroenterology. In 1951 Rubin completed a fellowship at the University of Chicago in gastroenterology.

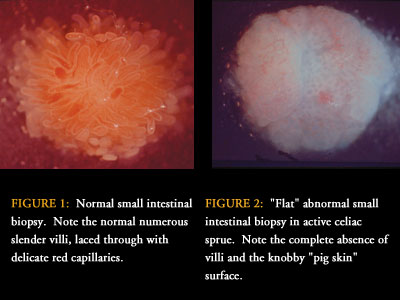

In the 1960s the fiber-optic technology of endoscopy changed the course of Rubin's research and gastroenterology. The first time Rubin saw the device he wrapped it around his neck, went into a phone booth, and looked through it, reading all the numbers on the telephone dial. According to Rubin this demonstration convinced him that the instrument could negotiate the curves of the intestinal tract and still produce a reliable, accurate picture of the interior as it proceeded. "Endoscopy changed the whole face of gastroenterology because we were able to make better and more accurate diagnoses," said Rubin. "We not only could see abnormalities in patients, but as the instruments improved, we could even take biopsies, stop bleeding, and remove gallstones without invasive surgery." Rubin and his engineering collaborator Wayne Quinton, a biomedical instrument builder who ran the instrument shop at the School of Medicine, have invented or improved a variety of devices used to sample the gastrointestinal lining. Their work contributed to the development of a flexible hydraulic biopsy tube that helps physicians take a sample within a patient's 20-foot long gastrointestinal tract. Rubin's sense of invention led him to create and participate in the bioengineering group at UW that developed endoscopic control of gastrointestinal bleeding using heat-generating probes. In 2000, after the slaying of UW GI pathologist Dr. Rodger Haggitt, Rubin helped Dr. Mary Bronner, associate professor of pathology, continue Haggitt's work. "The UW is a widely recognized center for gastrointestinal pathology," said Rubin. "I diagnose biopsies obtained via the endoscope. There can be 90 biopsies that come in every day." Rubin's present research is on earlier diagnosis and mechanisms of cancer development. Gastric cancer was a common problem when Rubin first came to the UW. "This kind of cancer was difficult to treat because the diagnosis was made too late. Fortunately, gastric cancer is now uncommon locally," said Rubin. Rubin and others in the field of gastroenterology are continuing to investigate the role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer as well as the efficacy of early diagnosis using frequent endoscopy with biopsies of the stomach. "For unknown reasons, gastric cancer has practically disappeared in Americans," said Rubin. "However, it is still common in immigrants and in most of the rest of the world. We're trying to learn why." |

||||||||||||||||

|

© 2003 - 2004 UW Medicine

Maintained by UW Health Sciences and Medical Affairs News and Community Relations Send questions and comments to drrpt@u.washington.edu |

||||||||||||||||