|

|

|

|

|

Three major methods of reproduction are evident among

animals found at Argyle Creek: egg laying, brooding, and free-spawning.

Because free-spawning is the dominant mode, many of the animals in Argyle

Creek, which are benthic as adults, go through a free-swimming planktonic

stage as larvae.

EGG LAYING

The deposition of fertilized eggs in a gelatinous mass

is used by only a few of the species in Argyle, including nudibranchs and

gastropods. The eggs take different forms, from soft ribbons of the nudibranch

Archidoris montereyensis to the hardened egg capsules of the whelk

Nucella lamellosa. These structures produce a veliger

larvae that, in the nudibranch, hatches from the embryo mass and spends

time in the plankton as a feeding larval form.

whelk, metamorphoses into the juvenile form within the

egg capsule, while in the nudibranch the veliger hatches from the embryo

mass and spends time in the plankton as a feeding larval form.

|

|

|

|

|

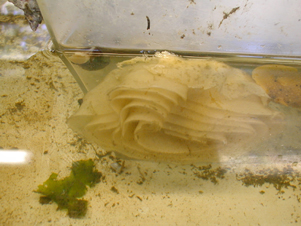

Lacuna is another snail that has internal fertilization,

but it deposits a different type of egg mass. Lacuna lay many

eggs in a gelatinous doughnut-shaped structure on algae. Veliger

larvae hatch and feed in the plankton for 4-6 weeks. One possible cue for

these larvae to metamorphose into benthic juveniles is the presence of

the algae that juveniles consume. Lacuna produces egg masses year-round.

Development time is highly

dependent on temperature--masses kept at a warmer temperature develop

much faster than those kept at a lower temperature. This suggests that

development of Lacuna in Argyle Creek--where temperatures

can vary by 10 degrees C on warm days--may be faster than where temperature

variation is less extreme.

|

|

| Nucella egg capsule in close-up view (left) and many capsules deposited on an abandoned tire at Argyle (right). | |

BROODING

The few animals that brood embryos at Argyle include the brachyuran crabs and the tiny brittlestar Amphipholis squamata. Brachyuran crabs hold their brooded embryos between the underside of the thorax and the abdomen, which is curled up beneath the thorax. Embryos hatch at a prezoea larval stage and then spend time feeding in the plankton until they settle out as benthic juveniles.

The brittlestar A. squamata broods its young until

it is a fully functional juvenile brittlestar that resembles the adult.

Eggs are fertilized and incubated in the genital bursae,

small pockets on each side of each arm. Ova are released into the

bursa singly and develop into small juveniles. Several embryos may develop

simultaneously in a single bursa. The bursal is thought to provide some

nourishment to the developing larvae. It is a remarkable experience for

the biologist to find even tinier offspring within the bursal slits of

tiny adults. Juveniles emerge from the bursa through the bursal slits

or through the aboral body wall of the parent. Sometimes the aboral portion

of the parental disk is shed prior to emergence of the juveniles. This

brooding technique results in the young finding the correct habitat when

released.

|

|

|

|

|

FREE-SPAWNING

Spawning is the most common reproductive mode for animals at Argyle Creek. These organisms release their gametes into the water column where fertilization occurs externally. The embryos live in the plankton for some time until they metamorphose and settle to become mature animals. Common free spawners include bivalves and some polychaetes.

The oyster Crassostrea gigas may shed gametes repeatedly over a season. This species was originally introduced from Japan and has now found a good niche in the waters of the Pacific coast. Crassostrea gigas spawns from late June through September, though initiation of gametogenesis depends on ambient temperature. Gametes are released into the mantle cavity and are ejected through rhythmic contractions of the adductor muscles. A single female can release up to 56 million eggs per spawning and over 90 million eggs in 1 month. Adults may also spawn repeatedly over one season. The zygote will develop into a straight-hinged veliger larva within 48 hours after fertilization. Larvae tend to vertically migrate in the plankton, spending time in the upper 2 meters at night and at 6-8 meters during sunny days. Veligers feed on algal cells under 10 micrometers in diameter. The veliger larvae are in the plankton for a period of 10 to 30 days, depending on the temperature of the water. Metamorphically competent pediveliger larvae settle and metamorphose within 36 hours after addition of crushed clean oyster shell. The shell has some form of indicator for the larvae to know that they are in a good place to settle.

Oysters are known to settle gregariously. Possible

reasons for the abundance of oysters in Argyle Creek is the warm water

in the lagoon and the proper chemical cues provided by other oysters for

metamorphosis. The lagoon may help to retain veliger larvae, promoting

settlement within the creek.

|

|

|

|

|