Within Eagle Cove there exist several zones containing

different assemblages of animals. Each zone provides special challenges

related to protection and defense. The major threats are posed by predators,

wave action, heat, and desiccation. Here we focus on a few examples

from each of the three habitats, paying attention to differences in environmental

conditions, availability of resources, and predatory threats.

Rocky Promontory

The rocky intertidal area of Eagle Cove undergoes

the most extreme temperature changes of the zones that we surveyed. During

high tide the temperature remains stable, but at low tide the temperature

can rise dramatically in a shallow pool. Most animals found in the intertidal

zone are ectotherms that cannot regulate their internal body temperatures.

Because many physiological processes rely on stable body temperatures,

the activity of many organisms is regulated by daily changes in conditions,

and some are known to produce heat shock proteins (HSPs) as a way to limit

thermal damage.

|

Aeolidia hunting Anthopleura

|

Many intertidal organisms are confined to

areas that remain relatively moist and cool at low tide. The sea anemone

Anthopleura elegantissima, for example, is commonly

found in shallow pools or crevices. At low tide they retract their tentacles

and compress their soft bodies to conserve water. When submerged, anemones

are subject to predation by the beautiful sea slug Aeolidia papillosa

, which stores the stinging cells of the anemone (nematocysts) for use in

the slugs' own self defense. It is not known how the slug is able

to consume nematocysts without being stung, or how it manages the transfer

of stinging cells to its own tissue.

|

Soft bodied polychaete worms are also

especially vulnerable to desiccation. The soft parchment-like tubes

secreted by sabellid worms are useful for protection from predators and

desiccation. Sabellids anchor their tubes in rock crevices where they are

protected from the rough surf. When exposed at low tide they retract their

feeding structures into their tubes. Many other polychaetes take shelter

in crevices or under the moist algae to prevent dehydration.

|

Sabellid worms retracted into their tubes at

low tide

|

|

Katharina blends in well with its environment

|

Molluscs like snails and limpets use

shells for protection from predators and environmental fluctuations. At low

tide these animals can pull their shells down against the rocky surface.

If pried loose by a hungry predator, snails will retreat completely into

their shells and use the operculum to close the aperture and shut off access

to the soft tissue.

Chitons can be difficult to spot in

tidepools because they often blend in well with the rocks and algae. They

are protected by calcareous plates that run down their backs and can also

resist predation by clamping the mantle area around the shell down against

the rocks. This makes it nearly impossible to pull the animal off of its

substrate and has the added benefit of conserving water.

|

Hermit crabs (genus Pagarus) use

empty snail shells for protection. This saves them the trouble and expense

of secreting a tough shell of their own, but it also means that as the

crab grows it must continuously locate new shells. We noticed that

many of the hermit crabs found at Eagle Cove have ill-fitting or damaged

shells, suggesting that optimal shells are in short supply. Hermit crabs

will typically retreat into their shells when handled, but crabs at Eagle

Cove often drop out of their shells and scurry away because they are too

large to retract completely inside. Perhaps the empty snail shells

are broken up when they are tumbled on the rocks by heavy wave action.

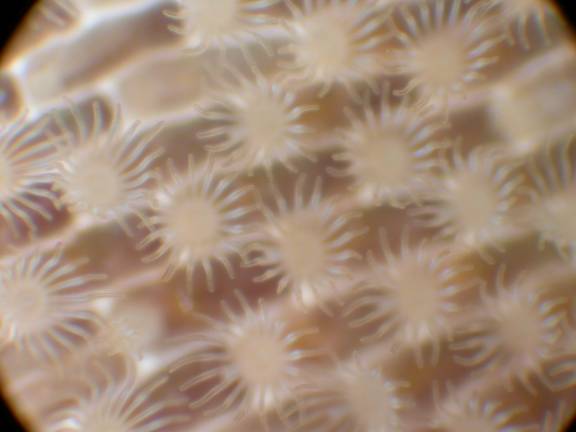

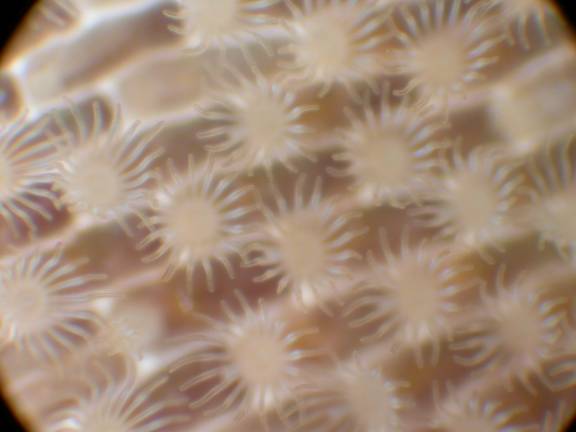

Bryozoan polyps and the rectangular skeletons

they retreat into

|

Bryozoans are soft-bodied sessile

animals that can often be found encrusting on rocks or algae. To the naked

eye, the colony looks like rough scales. Under the microscope one sees a

crown of tentacles associated with each zooid, in addition to a calcareous

outer skeleton. Bryozoans can retract their polyps into their skeletons

when they aren't feeding to protect the fragile polyps from desiccation

and attack.

|

Echinoderms like starfish can

protect their soft tube feet from hungry crabs by pressing their bodies

firmly against the rocky substrate when at rest. They are able to press

their stiff bodies to irregular surfaces or wedge them into crevices by shaping

the body using mutable connective tissue. Echinoderms have a water

vascular system that they use in locomotion and this system loses water

as they move so conservation is important during low tides. During low tide

they will retreat into crevices and halt their foraging activities.

Sea cucumbers have a

rather unique form of defense. If harassed by a predator the cucumber

can release sticky strands called Cuverian tubules from its anus. The

strands detach from the cucumber and entangle the predator, allowing the

sea cucumber an opportunity to escape.

|

Pisaster starfish resting at low tide

|

Cobble Area

|

Anomuran crab

Petrolisthes

|

The cobble area is

subject to rough wave action and cobble tumbling, and consequently many of

the animals found there have some type of tough exterior. Animals

in the cobble area, which is high in the intertidal zone, are also susceptible

to desiccation. There are some small pools under the rocks where most

creatures are found, but the low diversity of algae indicates that the

area is dry compared to the rocky promontory. Crustaceans and limpets are

well represented in this area.

Porcelain crabs (genus

Petrolisthes) are abundant under

the cobbles. They cling tightly to the rocks and if harassed they are likely

to autotomize (selectively release) a limb. This remarkable ability

helps the crab escape predation by freeing it from the predators grasp.

The limb will eventually regenerate during a subsequent molt.

|

The isopod

Gnorimosphaeroma oregonense

is also found in high numbers here. These crustaceans resemble the mottled

terrestrial roly-polys to whom they are closely related. This isopod is

found in aggregations under the cobbles and will roll up into a ball to

protect the vulnerable underside when disturbed. Idotea wosnesenskii

is another isopod found under cobbles. It's powerful jointed appendages

allow it to grip tightly to the rock surface.

Stuck to the

underside of many cobbles is a clump of wet sand that is, in fact, a tube

containing a terebellid worm. Terebellids construct their tubes out

of mucus and sand. The tube helps keep the worm moist, and keeps the

worm securely underneath the rock.

|

isopod Idotea

wosnesenskii

isopod Idotea

wosnesenskii

|

Sandy Beach

opposum

shrimp, Order Mysidacea

|

Sweeping a net through the sandy shoreline will reveal a surprising number

of small crustaceans, including mysids ("opossum shrimp") and cumaceans,

which are closely related to isopods. These animals are protected by their

sandy coloration and ability to burrow into the sand. There are also larger

shrimp here of the genus Crangon, about the length of a little finger.

They are extremely well camouflaged against the sand, and are best

seen after being caught in a dip net.

|

Between

the sand grains is a community, the meiofauna

, that exists and must gain protection at an entirely different scale. These

interstitial animals include several of the phyla with larger representatives

(like polychaetes, cnidarians, flatworms and crustaceans) as well as phyla

that are mostly small bodied (like nematodes and tardigrades). They

avoid abrasion from sand grains and wave action by adhering to sand particles

or by developing a tough exoskeleton.

[Eagle Cove Main Page]

- [Home]

isopod Idotea

wosnesenskii

isopod Idotea

wosnesenskii