Spring-Summer

2014

Robert L. "Bud" Burgner, 1919-2014

Marcus Duke & Tom Quinn

In 1945, Alaska was not yet a state and the bountiful salmon fisheries of this territory were in jeopardy because of poor management and a lack of scientific information. The Alaskan salmon industry approached the School of Fisheries Director, William F. Thompson, to develop a research program for sockeye salmon, which led to the formation of the Fisheries Research Institute (FRI) in 1947. Originally administered by the UW Graduate School, FRI joined the College of Fisheries in 1958.

Shortly before FRI was founded, Thompson hired his first staff member for the project: Robert Louis “Bud” Burgner (PhD 1958, UW Fisheries). Bud became FRI director in 1967, serving until his retirement in 1984. During his tenure, FRI’s research scope expanded greatly, pursuing studies on diverse aquatic species across a landscape that encompassed the northeast Pacific, and addressing critical regional, national, and international issues.

Robert L. "Bud" Burgner revisiting the Lake Nerka cabin built in 1949 (photo courtesy of the Alasa Salmon Program).

In the early days of FRI, Bud and his colleagues lacked many of the comforts of modern research, such as Goretex, Polartec, and reliable outboard motors. They even had to build the cabins they lived in. That they got work done under these conditions is remarkable.

Nearly seven decades later, the program that Burgner helped pioneer still prospers. The data sets initiated back then continue today, providing evidence of our changing climate and the scientific basis for sound management of salmon fisheries, with benefits to people and the entire ecosystem.

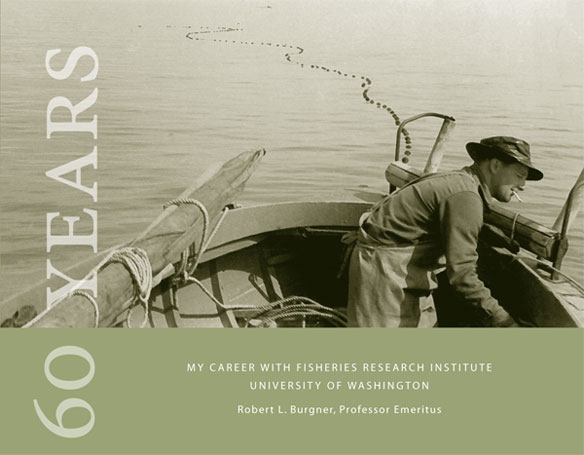

To learn more about Bud’s life, we recommend Bud’s memoirs:

His memoirs, which show the professional and personal sides of Bud, will continue providing many lessons for years to come from this account of one man’s life in fisheries research and conservation.

The following remembrances are from just a few of the many people who knew Bud as a teacher, a colleague, and friend.

Daniel Schindler

SAFS Faculty

Bud continued to interact with the Alaska Salmon Program (ASP) faculty, staff, and students long after his retirement from UW. He remained keenly interested in new research developments and was always happy to dig through his files to contribute to ongoing projects. It was often humbling to see that he and his students had worked on and answered many of the questions we continue to grapple with today.

His passion for scientific inquiry and for salmon never dwindled. In Bud’s last peer-reviewed paper (Bentley and Burgner 2011), he collaborated with Master’s student Kale Bentley (MS 2014, Schindler) to resurrect one of Bud’s earliest interests: interactions between salmon and their parasites. They compared the incidence of a tapeworm in sockeye salmon smolts migrating through the Wood River in the 1950s with rates observed in the last decade. Bud and Kale expected that the parasite load on smolts would have increased over this time period in parallel with the long-term warming of lakes but this did not happen.

Bud visited the ASP in the Wood River system in July 2005. It must have been quite a vivid trip down memory lane for him. He noted that many things were exactly like he remembered them, but that many others had changed. Numerous cabins had sprung up around the town of Aleknagik, and the vegetation had grown considerably around our Lake Nerka camp. He was amused by the fact that the cabin that he had started construction on in 1949 was still standing—although on wobbly logs.

Bud’s visit to Bristol Bay was particularly rewarding for me. In the boat ride from Aleknagik to the Nerka field station, our outboard motor sheared a flywheel pin about 5 miles from camp. It was a warm and sunny evening and the water was flat-calm. All Bud and I had with us was his overnight gear, a drum of gasoline, and a case of beer he brought along as a gift for the field crew. We spent the next three hours trading 10-minute shifts on the oars, sipping lukewarm beer, and reconciling what was fact and what was fiction from the good old days when Bud helped establish the ASP.

Until his death, Bud was a mentor, an invaluable source of information, and an inspiration to all of us who relish the privilege of contributing to a research and teaching program that he established almost seventy years ago.

Bruce S. Miller

FRI/SAFS Faculty

MS 1965, Allan DeLacy; PhD 1969, Lynwood Smith

Bud Burgner and I were very good friends from the time he was on my PhD committee. Bud (“Mr. Sockeye”) was fascinated by the dark field photography I used to photograph the egg stages of developing flathead sole and we spent most of my PhD oral general exam discussing that. While the Alaska salmon program was dear to Bud, he was also very interested in marine fishes and frequently discussed their biology and ecology with me.

Bud asked me to be the interim FRI Director when he retired. Thanks to him and Don Rogers (FRI faculty also studying Alaska salmon), I got a good dose of seafood company meetings and a wonderful trip to the FRI Iliamna research station to learn about Bud’s salmon research. Bud was a great teacher and, more than anyone, he seemed to appreciate the importance of long-term lake ecology studies in the management of sockeye salmon.

I also succeeded Bud as the Director for the Northwest chapter of the American Institute of Fishery Research Biologists (and FRI staff Kate Myers succeeded me!), but he continued coming to the meetings. The “Ken Chew Chinese Dinner Extravaganzas” were his favorite meeting venue: He would always greet and collect the tickets from the guests, most of whom he knew well and loved to chit-chat with—sometimes while he was slightly inebriated. The money and the ticket sales almost never matched up, but this was because he usually collected too much money!

For many years, Bud also organized the quarterly fishery retirees luncheon ("Old Friends of Fisheries" but also known as the “mossbacks”). Even when he was 90, Bud complained more than once to me at these lunches that he couldn’t find people to play tennis with that challenged him!

Kate Myers

FRI staff

When I started as a fisheries biologist at FRI in 1980, I was thrilled to meet Dr. Burgner, but it was several years before I was brave enough to call him “Bud.”

Bud Burgner in his FRI office. Photo courtesy of

Bud Burgner.

As Institute Director, Bud occupied the largest FRI office. His door was always open, and he always wore a tie. Bud was the brick and the mortar of FRI. He considered us his first responsibility and concern, and we sought to earn his confidence and respect in our scientific and professional activities.

Altlhough best known as a pioneer of Alaska salmon research, Bud was also was a leader in efforts to conserve salmon and steelhead migrating in international waters of the North Pacific Ocean. He spent over three decades on scientific work and deliberations with the International North Pacific Fisheries Commission (INPFC). This highly contentious issue brought considerable international social, economic, and political pressure on scientists; Bud and his colleagues from Japan, Canada, and the United States performed their work competently and with mutual respect. His tremendous aptitude for positively motivating and coordinating people to work together led to the development of a well-designed scientific research program that participating nations agreed upon.

Bud remained active after retiring, continuing his role as Principal Investigator of FRI’s High Seas Salmon Research Program for many years. In his final contributions to INPFC, Bud was the senior author of INPFC Bulletin 51 (1991), Distribution and origins of steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and the US Editor of the voluminous INPFC Bulletin 53 (1993), Symposium on biology, distribution and stock assessment of species caught in the high seas driftnet fisheries in the North Pacific Ocean. Although FRI and its long-term High Seas Salmon Research Program are now gone, Bud’s legacy to conservation of salmon and steelhead on the high seas of the North Pacific will forever live on.

Michael Dahlberg

PhD 1968, William Royce & Robert Burgner

Few people know that inquiries by Bud Burgner about the potential take of salmon in the northern area of the Japanese squid driftnet fishery in the North Pacific Ocean led ultimately to a nearly world-wide ban on large-scale driftnet fishing. Bud doggedly pursued the inquiry in the INPFC forum, and scientific observer programs were formed by the fisheries agencies of Canada, Japan, the republics of China and Korea, and the United States to monitor the squid and large-mesh driftnet fisheries.

Results of the observations indicated little take of salmonids but significant incidental catches of marine mammals and birds. Political controversy over the take of mammals and birds led to debate and later passage of the United Nations resolution that banned large-scale driftnet fishing.

Bud’s exceptional singing ability was revealed in annual INPFC Biology and Research social occasions with the other national sections usually out-performing the U.S. section. His performances of the song, Danny Boy, led to the Japanese scientists nicknaming him after the song…behind his back, of course. It was later revealed in his memoirs that he started singing in high school and formed a trio that performed in under-age establishments in Yakima!

Orra E. “Bud” Kerns, Jr.

FRI staff

FRI’s pre-season forecast for an exceptionally large Bristol Bay sockeye salmon run in 1960—normally a low-abundance year—was right on. The salmon industry benefited greatly from the forecast, and everyone was excited about this new method.

Bud motoring in the Wood River Lakes system, 1946. Photo by H. Gilmour.

I was working for FRI at the time, and I asked Bud for permission to buy a wet suit for making underwater observations of sockeye in the lakes. Bud said, “Okay, we have funding for one wetsuit.” This opened up a whole new world for us: In Iliamna Lake, I saw hundreds of thousands of salmon spawning along terraced beaches.

I told Bud, “You gotta see this!” But we had only one wet suit, which fit me exactly. Bud was much larger than me, but managed to squeeze himself into the small suit. I waited in the boat for nearly an hour, getting worried that something bad might have happened, when Bud surfaced. He said that he was so completely awed by the experience that he had lost track of the time. The following winter, Bud took a scuba course in Seattle!

Jeff Light

MS 1987, Robert Burgner

Bud was a quiet, thoughtful scientist with a remarkable penchant for accuracy and detail. I remember finding him deep in thought with a troubled look on his face, mulling over the functional difference between the terms “flotsam” and “jetsam,” or the proper use of the words “farther” and “further.” He shared this love with those he worked with and those he mentored. Usually this showed up as editorial comments on draft reports, where his red inkwell seemed bottomless. I think that sometimes the volume of his comments surpassed that of the original text. All for the best though: I credit him and those schooled by him for shaping my own writing abilities.

Bud was gentle, soft-spoken, and had an impish sense of humor. He was also an animal on the tennis court. As a doubles team, he and Bill Royce would win not by speed or power but by collective years of polished court strategy.

Jerry Pella

MS 1964, Robert Burgner; PhD 1967, Gerald Paulik

Bud treated his staff and students with uncommon kindness, tolerance, and respect and gave them the needed freedom to work out their projects and grow intellectually. I recall that he personally helped me during the hectic travel when I first arrived, young and confused, in Seattle from Minneapolis and left for Bristol Bay that first summer of 1961. He provided a lot of support, some direction, and a great deal of latitude for me in a thesis project, and he had a marvelous personality for dealing with young people.

C. Dale Becker

PhD 1964, Max Katz

In 1955, FRI Director Dr. Thompson and Bud made a trip to Corvallis to hire five MS graduates in Fisheries from Oregon State University. As one of those hires, I was assigned to help initiate FRI research in the Kvichak River. Bud was temporarily shifted from his first love, the Wood River Lakes, to jump-start efforts on the Kvichak.

Kvichak research started, basically, from scratch. Supply problems had to be solved, and quarters and equipment provided. Bud and a small crew arrived with plans to sample smolts as they left Lake Iliamna for the sea.

Bud was the catalyst behind organizing and supervising smolt sampling that first year on the Kvichak. He was the man with his hand on the throttle those cold Alaskan nights when the skiff carrying the crew putt-putted (noisily) downriver each evening and upriver during the wee morning hours. It was a job for men with spirit and purpose, filled with belief in what they were doing—common features among FRI field researchers. Bud was among the best of them.

Victor Bugaev

Russian sockeye salmon researcher

I can count on the fingers of one hand all the times I spoke with Robert Burgner in person. But I have felt his influence all my life. It was a true luck that I had some of his articles at the very start of my carrier. As a result, I was inspired to be a part of an international team of sockeye salmon researchers through the INPFC; Bud helped me find my own place in the scientific community, figure out my research directions, and begin to use standard approaches for data collection so that it could be compared with other data.

Victor Bugaev, FRI faculty member and long-time Alaska salmon researcher, Don Rogers, and Bud Burgner. Photo courtesy of Bud Burgner.